|

ALEXANDER SINCLAIR

From:- 'Who's Who in Glasgow in 1909'

Alexander Sinclair, the late managing partner of the Glasgow Herald was

born in 1828 at Campbeltown, and was educated there and in Glasgow,

whither he came in 1843. His business connection with the Herald began in

1845 by his answering an advertisement for a boy. He was the first boy

clerk the company employed, and he rose by successive stages in the office

from keeper of the petty cash to the positions of cashier, manager of the

commercial and publishing departments, and finally managing partner.

During the fifty-three years in which he served the company vast

changes took place. Five successive gentlemen occupied the editorial chair

- George Outram, James Pagan, William Jack, LL.D., James H. Stoddart,

LL.D., and Charles Russell, LL.D. In 1845 the Herald had one printing

press, wrought by two men, turning out 400 copies per hour; now it has

nine presses driven by electric motors, one of which alone can print,

fold, and deliver 1,000 complete Heralds in six minutes, and the paper

printed off for a morning issue runs to the extent of 126 miles. In 1845

the electric telegraph was unknown for newspaper purposes - the first two

or three lines of telegraphed news appeared in 1848; but in August, 1904,

the judgment and speeches of the Law Lords in the Free Church appeal case,

extending to 23½ columns, or about 45,000 words, came over the wires as a

single telegram. In 1845 the "taxes on knowledge" still existed - a penny

stamp on every printed copy sold or unsold, three halfpence per pound on

every kind of paper, and eighteenpence on every advertisement. To-day,

thanks to the legislation of 1853, 1855, and 1861, the entire industry is

duty free. In 1845 a copy of the Herald cost 4½d.; it was reduced to 1d.

and the issue made daily in 1859. Latest of all the improvements under Mr.

Sinclair, the Linotype composing machine has been introduced, by which the

operator fingering a keyboard can set, cast, and deliver in lines upwards

of seven thousand letters per hour.

The City of Glasgow itself has

changed not less in Mr. Sinclair's time. When he came to town the entire

space from Blythswood Hill to Argyle Street was laid out in corn fields,

and Sauchiehall Street, from Douglas Street to Sandyford, was a somewhat

marshy lane with a decayed dyke on the south side. To the architectural

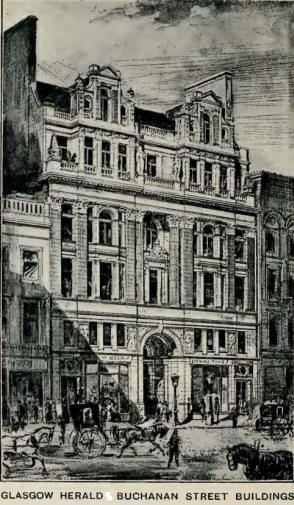

changes which have taken place Mr. Sinclair has contributed his part, for

one of his last undertakings in the active management of the Glasgow

Herald was the erection of the great new offices which form one of the

most striking features of Buchanan and Mitchell Streets.

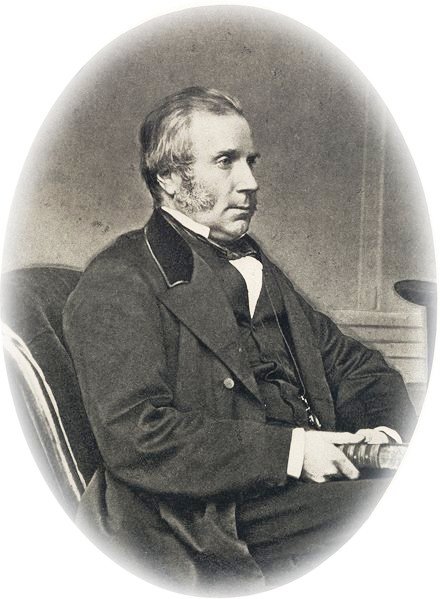

On the

completion of his fifty years' connection with the paper his co-partners

presented him with his portrait by Sir James Guthrie, now P.R.S.A.

(reproduced here), and all the employees combined to present him with a

hall clock with chimes and bells.

As with the Herald connection,

Mr. Sinclair's more public career was begun in a small way. When he went

to live at Langside about 1870 the roads of the district were almost

impassable, Battlefield being a mere narrow watercourse in much the same

state as at the time of Queen Mary's overthrow. He took an interest in

these roads, and improved them with ashes from the Herald furnace.

Presently he was made a Road Trustee, afterwards a County Councillor for

Renfrewshire, and when Langside was absorbed by the city he became

representative for that ward. Lastly, on the reconstituting of the whole

Town Council in 1898, by the rearranging of the twenty-five wards, he was

elected third senior Magistrate of Glasgow. It was upon his motion that in

1894 Camphill estate and mansion were purchased by the Corporation from

Hutchesons' Hospital for £63,000 and added to the Queen's Park. He also

took the initiative, as treasurer, along with Mr. A. M. Scott as

secretary, and Mr. Wylie Guild as convener, in the setting up of the

Battle Monument at Langside. And he was one of the founders of Camphill

U.P. Church. In recognition of his practical interest in the district the

committee of the Corporation gave his name to the road running from

Battlefield to the River Cart - which is now Sinclair Drive.

Mr.

Sinclair has travelled a good deal abroad, his latest and fourth ocean

excursion being one to Valparaiso, to visit his youngest son in business

there. He is the author also of a highly interesting volume, "Fifty

Years of Newspaper Life," printed for private circulation in 1895.

Contents

Note: The Chapters below are to pdf files.

James Pagan (1811-1870)

Editor of the

Glasgow Herald.

MR. JAMES PAGAN was for nearly thirty years a

prominent figure on the "Glasgow Herald." He was for nearly sixteen

years reporter and sub-editor, and for the last fourteen years of his

life editor and managing proprietor. Mr. Pagan was born in 1811, at

Trailflat, in the parish of Tinwald (about ten miles from Dumfries),

where his father was engaged as a bleacher. The family left Tinwald

for the county town a few years after Mr. Pagan's birth. He received a

sound education in the Academy there, getting as much Latin as served

with his retentive memory to cap a quotation not infelicitously. He

was subsequently apprenticed as a compositor in the office of the

"Dumfries Courier," then owned and edited by Mr. John McDiarmid, in

his time one of the best known editors in Scotland. McDiarmid, of whom

Mr. Pagan used to tell numerous stories, was a man of culture, of

enlightened views, based upon a substructure of strong common sense

and Scotch humour. After serving his apprenticeship as a compositor,

Mr. Pagan became a reporter on the "Dumfries Courier." In those early

years of the Scottish press the passport to the reporter's note-book

was through the case-room. The late Mr. Russel of the "Scotsman," who

was an early reporting associate of Mr. Pagan, also served his time as

a compositor. As a reporter he had to do all sorts of literary work

for his newspaper, and Mr. Pagan, having a clear and penetrating mind,

with considerable power of expression, soon made his mark upon the

"Courier." I have often heard him describe, as if it had only occurred

the day before, the exhumation of the body of Robert Burns in St.

Michael's Kirkyard, Dumfries, when Burns' widow, Jean Armour, was

buried. A host of phrenologists, headed I think by Mr. George Combe -

phrenology was then in its believable period - had assembled at

midnight to take a cast from the skull of Scotland's greatest poet.

Mr. Pagan was present to describe the proceedings for the "Dumfries

Courier" - an admirably graphic account by the way - and he used to

tell with reverential awe how he had held for a moment the skull of

Robert Burns in his hands.

With his proficiency as a short-hand

and his skill as a descriptive writer, Dumfries soon became too narrow

a sphere for Mr. Pagan's energies. His first ambition, however, was to

start in business for himself - a mistake as it turned out - for his

talent was that which the newspaper press most required. He was for a

short time partner of a printing firm in London, which was not a

success and he returned, as he would himself have said, "to his old

tunes again." In 1839, in the same year, and we believe on the very

week in which Samuel Hunter died, Mr. Pagan joined the staff of the

"Glasgow Herald," then published twice a week, on Mondays and Fridays.

It is needless to say that he threw all his energies into the service

of the journal upon which he was engaged. One of his first bits of

newspaper reporting, which attracted much attention, was his

description of the famous Eglinton Tournament, which took place amid

torrents of rain at Eglinton Castle. Pagan, in fact, was the first in

Scotland who really understood that the public wanted something more

and better than the bald and brief notices which then appeared of

public events.

He gave new significance and freshness to Town

Council and other meetings in Glasgow and in the West of Scotland; and

even the General Assembly, at that time distracted by the

non-intrusion controversy that led to the Disruption, was, in its

proceedings, brought graphically before the readers of the "Herald."

Looking at the side of the scenes, with the keen eye of the

professional newspaper describer, he saw what the public did not see,

and what he could not always describe as he saw it; but the

discussions of those days left a strong impression on his mind, and I

have often heard him describe them, with the side lights which his

retentive memory was able to throw upon the singular scenes that

preceded the Disruption. Mr. Pagan had not long been settled in

Glasgow, and done good work for the "Herald," till his high

qualifications as a reporter and descriptive writer, naturally enough,

became widely known. He was offered the chief place as reporter for

the "Times," and with perhaps some reluctance refused it, but he

remained till his death the most trusted correspondent of the leading

journal in Great Britain. His well known works, "Sketches of the

History of Glasgow" and "Glasgow Past and Present," were really the

fruit of his enterprise as a newspaper reporter. The "Sketches of the

History of Glasgow" originated in some slight descriptions of

lithographic views published by Messrs. R. Stewart & Co. in 1847; and

his "Glasgow Past and Present" was the outcome of his report of the

proceeding, of the Glasgow Dean of Guild Court, when, warned by the

fall of a sugar-house in Alston Street in 1848, by which several

persons lost their lives, the authorities thought it right to inspect

the condition of the many old buildings then remaining in Glasgow. Mr.

Pagan was the chronicler of their investigations, and as he added

original research to his descriptive reports, the matter grew rapidly

on his hands. Learned correspondents assisted him greatly with their

extensive knowledge of Old Glasgow, and among these may be mentioned

as facile princeps Mr. Reid, or "Old Senex," as he was tautologically

called, Dr. Mathie Hamilton, a personal friend of the late Pope Pius

IX., who wrote under the signature of "Aliquis," and J. B., who was

afterwards well known as John Buchanan, LL.D., a plodding and really

well-informed archaeologist. Mr. Pagan also wrote a "Guide to the

Glasgow Cathedral," a model of what a guide ought to be.

In

1841, two years after Mr. Pagan joined the staff of the "Glasgow

Herald," he married Miss Ann McNight-Kerr, a native of Dumfries, and a

relative of Mr. McDiarmid of the "Dumfries Courier." Miss Kerr had

long been a personal friend of Burns's widow, Jean Armour, to whom she

was in the habit of ministering till her death, and of whom she

related many anecdotes, greatly to the credit of Mrs. Burns's strong

common sense and kindliness of disposition. Mr. Pagan himself was a

relative of Allan Cunningham, though "honest Allan" was rather before

his day, but to the last he kept up some correspondence with Peter

Cunningham, a clever litterateur, but hardly a successor to his

father. At the time of his marriage Mr. Pagan had become tolerably

well known among the wits and geniuses of the Glasgow Bohemia -

Motherwell, Sandy Rodgers, Peter McKenzie, and others. Sandy

celebrated Mr. Pagan's singularly happy marriage by a copy of verses

which has only appeared, we believe, in a privately printed "In

Memoriam."(1)

In 1856, when Mr. George Outram died, Mr. Pagan

was appointed his successor as the editor of the "Glasgow Herald." He

had practically assumed the duties some time before in consequence of

the failing health of his chief, the sprightly laureate of the

Scottish Bar. At that time the "Herald" was a tri-weekly paper, but

Mr. Pagan was not long firmly established in the editorial chair when

the abolition of the last of the taxes upon knowledge determined the

proprietors of all the principal journals in Scotland to reconsider

their position. Some time before the newspaper penny stamp was taken

off, several new penny daily papers had appeared in Scotland in

defiance of the law, and when the tax actually ceased and made it

possible for journals to appear daily at a penny, those which were

spirited enough, not to be behind their times, had to bestir

themselves. The proprietors of the "Herald," of whom Mr. Pagan was one

at this time, rightly and promptly decided to "grasp the skirt of

happy chance" in this case, fortunately almost a certainty, and they

produced the paper daily at one penny. The productive power of the

printing press had about that time been enormously increased by the

ingenious invention of a New York firm, and with the aid of the new

rotatory printing presses the "Herald" at its cheap price could be

turned out to meet the greatly increased demand. Of course the task of

editing a daily paper was a new experience to Mr. Pagan, an onerous

and highly responsible one. The establishment of the paper as a

first-class daily cost him years of hard, incessant and worrying work;

but he had a genial temperament not too easily excited, and he was

ready in invention, quick in suggestion, and unfailing in sagacity. He

was hardly ever deceived by a sham, and he had the true instincts of

the trained newspaper man, for newspaper work. It is enough to say

that he succeeded thoroughly in establishing the "Glasgow Herald" as

one of the first provincial daily papers, and when he died in 1870 at

a comparatively early age - under sixty - his true work on the paper

may be said to have been completed.

Of the man himself, as of

every man, it is difficult to give a living picture. As many of the

readers of this sketch know, he was a little man, scrupulously

dressed, somewhat in the old fashion, scrupulously clean, with a fair,

reddish face, light grey and scanty hair, mutton-chop whiskers, and

the brightest of steel blue eyes, round and full. He was always

cleanly shaved, and if a speck could be seen on his glancing shirt, be

sure it was a speck of taddy from his snuff-box. He wore his old large

watch in his fob, attached to a black silk ribbon, at which depended a

large gold seal. There was a look of the old Glasgow gentleman about

him quite unmistakable, but different from the Glasgow gentleman of

his later days. The following slight sketch written immediately after

his death may recall the successful editor and genial companion:-

"Mr. Pagan's social days were on the wane when I became acquainted

with him, but I have often heard old friends talk of pleasant evenings

spent in his company, when he was the first and the last with song,

jest, and story. He heartily loved the old melodies, with which he had

a most extensive acquaintance, and could render them with fine effect

in a clear, sweet voice. When he died, the man who knew most of Burns

died also. My knowledge of most of the unbiographical details of

Burns's life, especially in Dumfries, was wholly derived from his

great store. In capping a story he was inimitable. It hardly mattered

what was the subject, there was sure to come ready at hand from his

humorous wallet something so funny and so pat that the table was

instantly in a roar. Latterly, however, it was only his intimate

friends who had an opportunity of hearing and relishing these humorous

sallies. He sang his friend Outram's songs with rare liveliness, and

it was a treat to hear him in half recitative trill over the best

Glasgow song ever written, 'Captain Paton.' And that reminds me that

Mr. Pagan was one of the last in Glasgow who could mix a 'bowl of

punch' as they mixed it long ago.

"Seated at the editorial

table Mr. Pagan has often restored harmony when some little jar

occurred, by a quaint story beginning 'That reminds me.' Friends who

called on him for a minute's talk on business were sure to go

sniggering away at some racy jest or story; and prosy bores, who, to

use his own expression, 'exhausted time and encroached upon eternity,'

with their long windedness, were deftly cut short and sent away

smiling. I can see him in his sanctum, his grey hair, and clear,

bright eyes, silver snuff-box in hand, ready for any kind of

reception. The snuff-box was indispensable. It was always consulted

with frequency and energy in every decision requiring careful

consideration and wise decision. It was generally poised in his hand

when he gave judgment, and its contents always used when he wished to

give energy to his words. It served also as a sort of memorandum box,

for amid the 'best brown taddy,' there were sure to be numerous little

slips of paper with short-hand hieroglyphics upon them reminding him

as he opened the box on arriving in the morning - the first thing he

did - of some little business to be attended to, or of some

good-humoured wigging to give to a subordinate."

Mr. Pagan was

the third editor of the "Glasgow Herald," counting from the time when

the paper emerged from the Saltmarket as the "Glasgow Advertiser," and

became in 1802 the "Glasgow Herald and Advertiser." It says something

for the stability of the editorial profession - if the phrase may be

used - that during the 103 years that the newspaper has existed there

have only been six editors, and when it is considered that the reign

of one - and one of the ablest - only extended to five years, it may

be granted that the seat of honour has been occupied on an average by

each for a long period. The birth of the "Herald" or "Advertiser" is

somewhat obscure.(2)

The "Advertiser" was started in 1782 by

John Mennons, aided by his son Thomas Mennons, printers and publishers

in the Saltmarket. Mr. Pagan used to say that, according to tradition,

the rent of the entire premises was only five pounds yearly. The

"Advertiser" began as a weekly evening newspaper, being issued on the

afternoon of every Monday, and it was printed by one of the old wooden

screw presses which had been in almost exclusive use at that time and

from the days of Caxton. The fragments of this old press are still in

existence. It was capable of producing one hundred complete copies in

an hour.(3) In 1793 Mr. Mennons removed from the Saltmarket to a shop

at the mouth of the Tontine Closs, the first shop west of the (then)

Glasgow Exchange. The removal was signalized by the "Advertiser"

becoming bi-weekly, Mondays and Fridays. Looking over what copies I

have seen of the "Advertiser," all of them belonging to the nineties

of the last century, it must be admitted that they afford curious and

interesting studies. Editorial duties were certainly light in those

days. There was no reporting - reporting would not have been

tolerated.

Yet I can easily understand how this newspaper, so

absolutely different from a newspaper of the present day, maintained

its position, flourished, and got numerous advertisements. It was a

newspaper without attempting to be a guide of public opinion. It sold

news and nothing else. There were few methods in those days by which

public opinion could be expressed in an independent manner by a

newspaper. The official opinion was considered the only public opinion

worth recording, and it was recorded in the briefest fashion.

The Mennons were the publishers and conductors of the "Advertiser,"

but there were other partners in the concern, as Mr. Pagan believed,

though who these were is not now known.

In 1802 the

"Advertiser" entered upon a new career. Dr. James McNayr was the

printer and publisher, and new blood had been brought into the

concern. Thomas Mennons still retained an interest, but there was a

new copartnery, and the chief moneyed man was Mr. Benjamin Mathie, the

uncle of the Dr. Mathie Hamilton, to whom reference has already been

made. Dr. James McNayr had been for many years the principal conductor

of the "Glasgow Courier," and his connection with the metamorphosed

paper, the "Herald and Advertiser," lasted only two months. As he had

evidently during that short time controlled the destinies of the

paper, it may be fairly assumed that his exertions had not been

appreciated, for on January 3rd, 1803, an announcement appeared to the

effect that the proprietors, Messrs. Mathie & Mennons, had formed a

connection with a gentleman of "considerable literary abilities," from

whose exertions "they trust the public will receive satisfaction."

Next week it was stated that the gentleman was "Mr. Samuel Hunter of

this city." The connection of the Mennons with the "Herald and

Advertiser" ceased in 1805, but it may be interesting to state that

the man who started the "Advertiser" had enlarged views, and before he

came to Glasgow had been concerned in literary work in Edinburgh, and

had devoted his attention to the development of the coal and iron

fields of Ayrshire. Others reaped advantages from his intelligence and

foresight. Some members of the Mennons family are still living.

The appointment of Mr. Samuel Hunter as editor and chief

proprietor of the "Herald and Advertiser" in 1803 marked a new era in

its career. When Mennons finally retired in 1805 the title of the

paper became, what since it has always been, the "Glasgow Herald," and

thus two years after Mr. Hunter was installed he became universally

known in Glasgow as Sam Hunter of the "Herald." Associated with Mr.

Hunter as proprietor and literary assistant was Dr. William Dunlop.

His father, Alexander Dunlop, was an eminent surgeon in Glasgow. His

son William was an able man, and surgeon, but had no great love for

his profession, and this probably is the reason that he drifted to Mr.

Samuel Hunter.

Dr. Dunlop's health failed, and he died in the

island of Tenerife in 1811.

Mr. Samuel Hunter, the real founder

of the "Herald," was the son of the parish minister of Stoneykirk,

Wigtownshire, and was born in the manse there in 1769. He was educated

for the medical profession, and at the close of the century he served

with the troops in Ireland as surgeon, and thus took part in the

suppression of the rebellion of 1798. He became a magistrate of

Glasgow, and colonel of the Glasgow Highland Volunteers. He was for

many years one of the most popular men in Glasgow, perhaps the most

popular, and people never tired of repeating his latest bon mot. His

wit was infinite in its variety, and the stories told of him are

endless, but many of them are so well known in Glasgow society that

they need not be repeated here. Probably the wittiest and the most

humorous of them could hardly be translated into modern English.

He was a tall, stout man, with commanding features, as his

portrait by Macnee shows. To put it plainly, he was very fat, and I

can never forget, as illustrative of the physical infirmities of the

big man, Mr. Pagan's story of Hunter walking along the Trongate in a

melting August day, puffing and whispering to himself, "I wish to

heaven it was frost."

Mr. Hunter retired in 1837, and about two

years afterwards died in the manse of his nephew, Dr. Campbell,

minister of Kilwinning. He lies in the churchyard of the old abbey, a

"throughstone" over his grave. As a convivialist and diner out he had

no equal in Glasgow, and has had no successor. But his judgment was as

good as his wit. It only once failed him, for it led him astray on the

great Reform Bill of 1832. He opposed it, and nearly perilled the

prosperity of his paper, but the bad time passed over and Mr. Hunter's

popularity revived. Many years ago, when residing for a few holidays

at Kilwinning, I almost daily visited the last resting-place of Sam

Hunter. It lies in a kindly nook beneath the three lance windows that

are nearly all the remains of the ancient abbey of Kilwinning. When

seated on his "throughstone," many years ago, I remembered some lines

that an admirer had written:-

"Fun ever still the

banquet lit,

Where Sam was present guest or host,

And Glasgow

lost its broadest wit

When Death took off his laughing ghost.

Alas! poor Yorick: few remain

Who now recall the jester's ways,

To whom his stories still retain

The flavour of his happiest

days.

The jest is gone; the work is o'er,

Laborious work it

lasteth yet,

And may for generations more

Forget the worker

and the wit.

Sleep sweetly in this nook obscure,

A quiet nook

wherein to stay,

Till the last summons finds thee sure,

And

jest on lip thou goest away."

Mr. Hunter was succeeded as editor and

as one of the proprietors of the "Herald" by Mr. George Outram,

advocate, a humourist in some respects superior to his predecessor,

though not with the same force of character. He edited the "Herald"

from 1837 to 1856, a period of nineteen years, and it is sufficient

evidence of his editorial qualities that the "Herald" greatly

flourished under his reign. There is nothing particular, however,

connected with the history of the newspaper which calls for special

record during his occupancy of the editorial chair. Things went

smoothly as he sat there, and perhaps the only notable event which may

be recorded is that, though a Tory of the old school, he cordially and

thoroughly adopted the principles of free trade as enunciated by

Cobden and Bright. Hence in the struggle for the abolition of the Corn

Laws the "Herald" was on the right side.

Mr. Outram's

reputation, however, rests upon his humorous poems, embodied in the

"Legal Lyrics," a little volume which is likely to live as long as

Scottish wit and humour are understood and appreciated. Mr. Outram,

who was a cousin of Sir James Outram, the Bayard of India, was a man

of high culture, of loveable disposition, and the friend of nearly all

who were in his day eminent at the Scottish Bar and on the Scottish

Bench. His name is reverently remembered, and his songs are still

joyously sung in lawyers' convivial feasts in Edinburgh. At his death,

as I have already stated, Mr. Pagan took his place and held a firm

grip over the "Herald" for fourteen years. After his death Mr. William

Jack, the distinguished mathematician, succeeded him, and reigned over

the destinies of the "Herald" till 1875, when he left for a place of

greater ease and dignity. Since then the history of the "Herald" is

modern history, and not in the meantime to be related.

(1) One

verse very fairly describes Mr. Pagan when he had just entered upon

his thirties -

"He spins a good story, he weaves a

good tale,

He lilts a good sang owre a tankard o' ale;

He

cracks a sly joke too, wi' humorous glee,

But nane lashes vice so

severely as he.

And ilk body likes him whaurever he gangs,

Sae

fond o' his stories, his jokes, and his sangs;

But the thing he's

maist prized for by every degree,

Is the generous heart ever open

and free." (2) The exact date of its first appearance is not known.

Mr. Andrew Macgeorge in his History of Glasgow, a careful book, states

that the "Advertiser" was first published in 1783. This I have

ascertained is a mistake by a year. Mr. Pagan, who naturally knew more

of the early history of the paper than any other person living,

produced in 1868 several facts to show that the "Advertiser" first

appeared in June or July, 1782. What has led to this uncertainty is

the complete disappearance of the "Advertiser" files They were at one

time, it is understood, in the possession of Mr. Mackenzie of the

"Greenock Advertiser," but after his death nothing further could be

heard of them. Through the perseverance, however, of Mr. Sinclair, one

of the managing proprietors of the "Herald," a number of the yearly

volumes of the "Advertiser" have been recovered, and though it is

evident from these files that great carelessness was shown in the

numbering of each paper (complicated by the want of knowledge of the

exact date at which the "Advertiser" became bi-weekly), still the date

1782 cannot be disputed after making every allowance.

(3) The

"Herald" machines can now each produce 100,000 copies per hour,

printed and folded, of the "Evening Times" size, which is about double

the size of the "Herald" of 1802.

Sketches of the History of Glasgow

By James Pagan

|