Fortis in arduis (strong in

adversity) is a particularly appropriate motto for the Findlays of

Boturich, a family which has, at times, enjoyed great wealth but at others

suffered considerable losses, more than once as a consequence of historic

accidents of fate. Today, Robert Findlay, 8th of Boturich,

Dunbartonshire, the eldest Findlay male and the family historian,

humorously describes his own family as "stranded gentry" – a

delightfully evocative term.

With the help of the family Red Book or Leabhar dearg,

Robert Findlay has traced his family line back to one Findla (or Findlay)

Mhor, a giant of a man with great strength who, bearing the royal banner,

was killed at the battle of Pinkie in 1547. According to the 1849 edition

of Burke's Landed Gentry, Findla Mhor "was buried in the

churchyard of Inveresk, at a short distance from the field of battle. No

monument was erected to his memory, but the place was long known in that

parish by the name of the Long Highlandman's Grave"…

"In those days", notes Robert, "Scotland

was not a wealthy land and for most it was enough to subsist from the

fruits of soil or sea. This imposed severe limitations on enterprise;

foreign trade was almost non-existent. Any spare taxable wealth was

usually needed to pay, or fight, the English."

By the seventeenth century, the Findlays had become

prosperous merchants in Kilmarnock, a somewhat restricted activity

geographically at that time because the Scots were effectively barred from

trading with the English colonies. Hence the Act of Union in 1707 gave a

considerable fillip to the family fortunes. Robert Findlay explains that

"the union of the parliaments of Edinburgh and Westminster was

strongly debated and opposed at the time. But soon after this, the new

Edinburgh arose to be called the Athens of the North, while Glasgow's new

trade brought previously undreamed-of wealth flowing into the country as

adventurous Scots were suddenly able to compete on equal terms with

English traders under the powerful protection of the Royal Navy.

"The entrepreneurial younger sons of the Scottish

gentry, who were not constrained by the duty of looking after family

estates, sailed away to set up trading ventures with the colonies, making

their names as Virginia merchants and in the Caribbean, and then as East

India merchants and in other far-flung destinations including South

America and China. While, in those days, such ventures often meant long

and arduous sea journeys, fraught with dangers, the potential prizes were

irresistible."

Colonial adventures

The Findlays initially turned their sights westwards,

towards America.

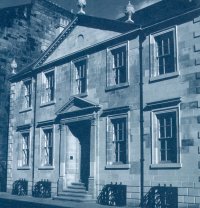

Sixteen-year-old

Robert Findlay sailed for six weeks across the Atlantic in 1764, to join

two uncles in Virginia. When he returned home, having amassed a

considerable fortune, he bought a town house at 42 Miller Street in

Glasgow, then one of the best houses in the merchant city, where his son,

also named Robert, was born. He also bought a country house called

Easterhill, a few miles up the Clyde, which from 1784 to 1895 was a

Findlay home. Today, sadly, it no longer exists. The house at 42 Miller

Street continued its existence as a townhouse and has recently been

restored to its original state as a typical tobacco merchant's house of

the time.

Sixteen-year-old

Robert Findlay sailed for six weeks across the Atlantic in 1764, to join

two uncles in Virginia. When he returned home, having amassed a

considerable fortune, he bought a town house at 42 Miller Street in

Glasgow, then one of the best houses in the merchant city, where his son,

also named Robert, was born. He also bought a country house called

Easterhill, a few miles up the Clyde, which from 1784 to 1895 was a

Findlay home. Today, sadly, it no longer exists. The house at 42 Miller

Street continued its existence as a townhouse and has recently been

restored to its original state as a typical tobacco merchant's house of

the time.

The revolt of the colonists and the American Declaration

of Independence led to ruin for many wealthy Glasgow citizens, but not

all... One of Robert Findlay's uncles cannily "did the rounds"

of the ruined merchants, buying their Glasgow tobacco stocks from them at

double the original cost. The merchants were happy at this, until the

market price soared well past that level – with supplies no longer

available. The fortunate speculator built himself a magnificent mansion

house, said to be the finest in the land at the time. This house still

stands today inside the front part of Glasgow's Royal Exchange.

The Findlay family then turned its sights eastwards,

becoming timber merchants in Burma, and establishing trading posts in

Manila in the Philippines. Little is known about the business in the

Philippines, although trading continued until shortly after the First

World War.

The

Burma operation, T D Findlay and Son Ltd, East India Merchants, was set up

in 1839, being founded by and named after the current Robert Findlay's

great-grandfather. "It was a private family company, the smallest of

the five British teak firms in Burma", explains Robert, "but

when it was nationalised in 1948, it was Britain's oldest existing trading

connection with Burma. The company felled trees in the Shan States and the

Pegu Yomas, after ringing them to dry out on stump for a few years. To

ensure future supplies, for every tree felled, five saplings were planted.

The

Burma operation, T D Findlay and Son Ltd, East India Merchants, was set up

in 1839, being founded by and named after the current Robert Findlay's

great-grandfather. "It was a private family company, the smallest of

the five British teak firms in Burma", explains Robert, "but

when it was nationalised in 1948, it was Britain's oldest existing trading

connection with Burma. The company felled trees in the Shan States and the

Pegu Yomas, after ringing them to dry out on stump for a few years. To

ensure future supplies, for every tree felled, five saplings were planted.

"A couple of hundred contractors' elephants then

dragged the logs to the nearest floating stream to await the rains which

would carry them to the main river. Here they were turned into rafts large

enough to carry a whole family downstream to a railhead or to the base in

Moulmein where the logs were sawn into saleable products, latterly

including fine tongue-and-groove parquet flooring.

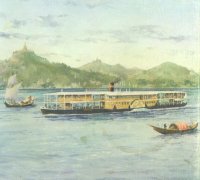

"But T D Findlay's finest achievement was the

creation of the Irrawaddy Flotilla, a fleet of over 600 shallow draught

ships, built in Dumbarton by T D Findlay's co-founder Peter Denny, whose

statue still stands in that town. The ships were specifically designed to

navigate the Irrawaddy and they became the lifeblood of the nation's

prosperity, ensuring trade up and down the great rivers, and aiding

Burma's transformation into the rice-bowl of Asia."

But

this exotic industry was to come to an abrupt end when the Japanese

invaded Burma in November 1941. The company scuttled its flotilla to

prevent it falling into the hands of the Japanese, "and this

action", notes Robert Findlay, "brought Burmese trade and

transport to a standstill. The flotilla had been the greatest-ever fleet

for river transport in the world. The teak business paid off its

employees, and dispensed with the elephants. In 1945, following the

liberation of Burma by the 14th Army, the family endeavoured to

build up the Burma business once again, only to see it nationalised by the

new, independent Burmese government in 1948" – a catastrophe for

the Findlay family which saw its capital decimated.

But

this exotic industry was to come to an abrupt end when the Japanese

invaded Burma in November 1941. The company scuttled its flotilla to

prevent it falling into the hands of the Japanese, "and this

action", notes Robert Findlay, "brought Burmese trade and

transport to a standstill. The flotilla had been the greatest-ever fleet

for river transport in the world. The teak business paid off its

employees, and dispensed with the elephants. In 1945, following the

liberation of Burma by the 14th Army, the family endeavoured to

build up the Burma business once again, only to see it nationalised by the

new, independent Burmese government in 1948" – a catastrophe for

the Findlay family which saw its capital decimated.

Life at Boturich

Going back just over a century, in 1839 the then Robert

Findlay purchased the Boturich estate in Dunbartonshire from the executors

of his maternal grandfather's estate. At his early death, the Boturich

estate passed to his father, who was also called Robert. The Easterhill

estate, just east of old Glasgow, on the banks of the Clyde, was at that

time inhabited by a junior branch of the family. The father of the current

Robert Findlay was a member of this junior branch and, in 1930, he

acquired Boturich and established his family home there, bringing family

pictures and furniture that were formerly in Easterhill. He also

substantially restored and extended Boturich.

The current Robert Findlay was born a decade or so

before these events, latterly growing up at Boturich with a brother and

three stepbrothers. His mother had died when he was five and his father

married again. He was a teenager when war broke out: "I was doing my

school certificate at Harrow when the war began," he explains,

"and we spent hours between exams digging trenches across the rugger

fields to stop gliders landing. Harrow also had its share of firebombs.

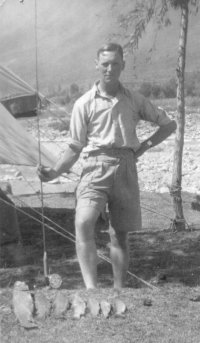

"I

spent the first winter after leaving school as an apprentice chartered

accountant in Glasgow and was called up in the spring of 1942 to the Black

Watch depot in Perth. After a stint with the Officer Cadet Training Unit

in Morecambe, I became a junior officer in the Indian Army and was shipped

out to the 8th Gurkha depot in Quetta (now West Pakistan) and

then on to the 4/8th Gurkha battalion which took me from Kohima

in the north down to the Sittang bend in the south of Burma. En route I

was wounded and evacuated, rejoining the battalion later.

"I

spent the first winter after leaving school as an apprentice chartered

accountant in Glasgow and was called up in the spring of 1942 to the Black

Watch depot in Perth. After a stint with the Officer Cadet Training Unit

in Morecambe, I became a junior officer in the Indian Army and was shipped

out to the 8th Gurkha depot in Quetta (now West Pakistan) and

then on to the 4/8th Gurkha battalion which took me from Kohima

in the north down to the Sittang bend in the south of Burma. En route I

was wounded and evacuated, rejoining the battalion later.

"I was away from the UK for four years, journeying

post-war to Bangkok, Malaya and Java. In early 1947, aged 23, I was

demobilised. Like most British officers, I was full of admiration for the

Gurkhas and it was with heavy heart that I left my men when I returned

home. Today I still feel a warm glow when I look back on my former life as

a Gurkha BO [British officer] – distance lends enchantment to the

memories.

"In Glasgow I completed my chartered accountancy

qualifications and, while doing so, became involved in several other

enterprises, including acting as shore manager for Gavin Maxwell's shark

fisheries, and helping to install Great Britain's first overhead ski tow,

at Glencoe.

"All

along, I had intended to join my father in the family business, but only

did so to complete its winding-up after my father died in 1950.

Subsequently I worked in various industries, ranging from nuts and bolts

and railway engines to biscuits, before setting up my own shop-fitting

business on Clydeside.

"All

along, I had intended to join my father in the family business, but only

did so to complete its winding-up after my father died in 1950.

Subsequently I worked in various industries, ranging from nuts and bolts

and railway engines to biscuits, before setting up my own shop-fitting

business on Clydeside.

"During this time I felt constrained to stay within

reach of Boturich. In 1957 my stepmother gave up the life-rent of the

estate and, with a bachelor brother, I took it over. We had some splendid

parties there, benefiting from the tennis court and the boat on Loch

Lomond, which bounded the estate along its western shoreline, and

organising bonfires and shotgun weekends! Latterly there was water-skiing

to keep our parties busy. I also managed to dance on most of the main

ballroom floors of Scotland, from Skye to the Borders, and enjoyed a

week's stalking in Mull every autumn (having once captained the Harrow

VIII, I fancied myself as a shot). All this was fitted in between the

daily drive to 'the office', wherever that happened to be.

"Marriage came when I was 41 and Liisa joined me

from her home in Finland, where I had met her on a forestry visit. We

married in 1964 and the next ten years totally changed my life by adding

three more to Boturich's resident family: a boy followed by two girls, all

of whom are now grown up and, with their spouses, a great joy to us."

A new life at Knockour

"We all had fun living in the parts of Boturich we

needed. But, in 1984, Lisa and I were forced to sell up and leave 'the big

hoose' and its home fields. We had been fortunate to stay so long, but the

situation we faced was very different from that experienced by my father

when he moved there in 1930. We did not enjoy Burmese business support and

heavy marginal taxation was throttling the growth of business enterprises.

We were also faced with heavy death duties on the death of my father.

"Consequently,

we sold Boturich and its nearby fields and built ourselves a special

kithouse called a Scandia-hus where the kennels had stood and from

where we enjoy unrivalled views down to the loch and the hills behind. Our

house arrived on three long lorries despatched from the Swedish factory,

ready to erect. Complete it looks remarkably like an old style building

– in stone with lath and plaster internal walls. The differences are its

plus points: no draughts, thick insulation, triple glazing throughout, and

attractive architectural design.

"Consequently,

we sold Boturich and its nearby fields and built ourselves a special

kithouse called a Scandia-hus where the kennels had stood and from

where we enjoy unrivalled views down to the loch and the hills behind. Our

house arrived on three long lorries despatched from the Swedish factory,

ready to erect. Complete it looks remarkably like an old style building

– in stone with lath and plaster internal walls. The differences are its

plus points: no draughts, thick insulation, triple glazing throughout, and

attractive architectural design.

"My

wife has made it our ideal home and is delighted by the change. I confess

mainly to a feeling of relief at extracting myself and my family from an

untenable position and leaving a house that I had grown to love for other,

better-endowed hands to care for.

"My

wife has made it our ideal home and is delighted by the change. I confess

mainly to a feeling of relief at extracting myself and my family from an

untenable position and leaving a house that I had grown to love for other,

better-endowed hands to care for.

"In 1960 I had become an underwriter at Lloyd's. We

were not long into our new abode in the 1980s when the Lloyd's disaster

struck, and for a time we faced bankruptcy as half a million in losses

drained any liquid reserves. Fortunately we then enjoyed three splendid

years before pulling out of Lloyd's at the end of 1996, in relief, sadder

and poorer but possibly wiser.

"We still maintained most of the former estate's

1000 acres, and especially Knockour Wood along the shore and Knockour Hill

which rises to some 650 feet in the centre. These gave the local name to

our new house. Now it is to Knockour estate, rather than to Boturich

estate, that I devote my time and interest. I am its 'caretaker' in many

ways, from the annual grazings to the planting and felling, the care of

roads, drains, fences and water supplies, and the accounting of costs

among the community of owners who bought the cottages and use the roads.

"I loved my young days planting up the woods here,

but I never thought I'd be reaping them too. Near sea level in the mild,

wet West of Scotland, they grow fast. Within the estate's Woodland Grant

Scheme, some field areas have been turned over to Nordman Christmas Trees;

elsewhere, the land is providing sites for masts to serve mobile telephony

– all this helps the land pay its way. We are soon to gain a mains water

supply, as we did electricity a few years ago, replacing the countryside's

current 'DIY' arrangements.

"Today I would describe the Boturich estate as an

owner-occupier neighbourhood of road-sharing, minor capitalists who enjoy

the countryside quiet and neighbourhood security – a practical and happy

solution to many needs, ours and theirs. I'm unexpectedly approaching my

eighties, but not yet allowed 'off-duty'. And reliving our family history

for Burke's Landed Gentry is helping to keep me out of

mischief."

The Findlay family in June 2000 at the wedding at Knockour of Anne, youngest daughter of Robert and Liisa, to Niall Jenkins. From left to right: middle daughter Alex, Robert, Liisa in Finnish costume, Anne and Niall, Liisa's 93-year old mother, Mrs Ahtiala, from Helsinki, Rob Findlay and his then fiancée Aoife (they married in Tipperary in December 2000).

Our thanks to Burkes

Landed Gentry for this story