|

| |

Mini

Biographies of Scots and Scots Descendants (B)

Brown, Joseph E. |

Scots/Irish

originally from Scotland Scots/Irish

originally from Scotland

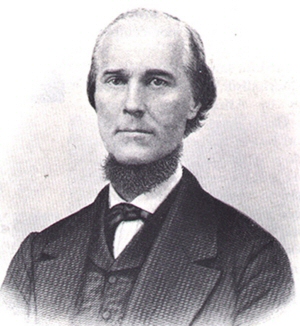

Joseph E. Brown

a North Georgia Notable

Born 1821, South Carolina

Died 1894

Joseph E. Brown: Businessman,

Educator, and Politician

by Carole E. Scott

Georgia's Joseph Emerson Brown was

a self-made man successful in both business and politics who became

rich, in part, by adroitly using his political power to foster his

extensive business interests. Being on the losing side of The War

Between the States undoubtedly slowed down his acquisition of wealth,

but it did not even temporarily impoverish him. It was what he said, and

what he did; not charisma, that won elections for Joe Brown, as he was

not very likable; neither a good speaker or good looking; and came from

a humble background in a day when most of Georgia's political leaders

came from the elite planter class. The only man to have four times been

elected governor of Georgia, conceivably, if he had not been forced to

resign as a result of the defeat of the Confederacy, he could have been

reelected to a fifth term. He also served the State as a circuit judge,

state senator, chief justice of the Georgia Supreme Court, and U.S.

Senator. (While in his day Georgia's governors were elected by popular

vote, U.S. Senators were elected by the state legislature.)

Georgia Governor

Joseph E. Brown

He was the owner of iron and coal companies in Northwestern Georgia

(mostly Dade County); the president of the firm that after the war

leased the State-owned Western & Atlantic Railroad; and a large investor

in real estate and stocks and bonds.

Georgia's coal and iron deposits

were largely undeveloped until after the Civil War, when Brown began

mining operations. He realized the potential of railroads in general

both in economic development and as a field of investment. Besides that,

railroads fascinated Joe. Mixing business with pleasure, he often spent

days riding up and down the Western & Atlantic's line connecting Atlanta

with Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Because the governor chose to say

little about his investments and placed no value on them in his will, it

is impossible to accurately measure how wealthy he became, but in 1881,

while serving in the U.S. Senate, The New York Times reported that Brown

was worth one to two million dollars. [July 2, 1881] At his death some

estimated his wealth at up to $12 million.

Brown's contribution to Education

Called "The Ploughboy" before the

war by planter enemies because he came from a non-slave owning family,

he moved to North Georgia after his birth in the Upcountry of South

Carolina in 1821. In this mountainous part of Georgia's Upcountry there

where few educational opportunities; so when he was 19, clad in homespun

clothes, he traveled to South Carolina, where he traded a yoke of oxen

for room and board and arranged to attend the Calhoun Academy on credit.

Upon his return from that school,

Brown taught school in Canton, Georgia and studied law in his spare

time. Without ever having read a day in a lawyer's office, he was

admitted to the bar in Canton [Cherokee County]. He also worked as a

tutor. Throughout his life he sought to prevent others from having to

struggle as he had in order to get an education. As Georgia's governor

in 1858, he advocated that schools be established so that every "free

white child" would have the right to attend. "Let," he said, "the

children of the richest and the poorest parents in the state meet in the

school room on terms of perfect equality of right..." This was needed,

he believed, because the State's lack of development was for want of

education. While he did not get all he asked the legislature for, it did

set aside money from earnings of the Western & Atlantic (W&A) to educate

white children.

Brown served on the University of

Georgia's board of trustees from 1857 to 1889. He served, too, as

president of the Atlanta Board of Education from 1869 until 1888. His

contribution to education in Atlanta was recognized after his death by

the naming of a now closed high school (originally a junior high school)

in his honor. When he was in the U.S. Senate, Brown said that the

federal government should finance the education of children of all

classes and both races. He did not agree with those who said the

education of the people was not a federal responsibility because "we do

not live under the Constitution that we lived under" prior to the War

Between the States. This was due to the fact that its powers had been

greatly expanded since then.

In 1845, after passing the bar,

Brown enrolled at Yale's Law School, financing this with money borrowed

from a Canton physician who he would later, as governor, appoint to head

the State-owned railroad, the Western & Atlantic. After receiving a

Bachelor of Law degree in 1846, he returned to Cherokee County, where he

practiced law and married the daughter of a local Baptist preacher.

Before 1865, Brown was a

Jacksonian Democrat who shared Jackson's belief in the spoils system;

his anti-bank philosophy; and his appeal to the common man. An adroit

opportunist, he was so devoted to states' rights that many historians

believe that as Georgia's governor he hindered the Confederacy's war

effort.

As governor, he replaced both the

top management of the W&A and many minor officials with supporters. He

instructed the Road's superintendent "to cut all unnecessary expenses,

but keep the railroad in good repair; dismiss all employees who were

supernumeraries or not absolutely necessary to the operation of the

road. Where salaries were found to be higher than those paid for similar

service on other railroads they were to be reduced. He was to require

'absolute subordination, and prompt obedience to orders.' All employees,

regardless of position, who were known to use 'intoxicating liquors of

any kind' as beverage or were engaged in 'gaming' or 'any other

dissipation of immorality' were to be dismissed. Strict economy was to

be required in even small transactions....'Prompt obedience to these

orders will be required. That they may not be misunderstood by any, you

will have them printed and a copy delivered to each officer and employee

on the road.'"

After the War, he became a

Republican and moved to Atlanta, which the Republicans who then

controlled the state government had made the State's new capital.

Despite having allied himself in both politics and business with

carpetbaggers and scalawags, after the State was "redeemed," he returned

to the Democratic Party. He then became a member of a group of Atlanta

politicians and their handlers called by various people at various times

the Atlanta Ring or the Kirkwood Ring. (The chief handler was Henry

Grady, editor of the Atlanta Constitution.) For many years, Brown and

two other members of this group, called the Bourbon Triumvirate,

dominated the State politically. As a Democrat, Brown was appointed to

and subsequently elected to the U.S. Senate.

In a December 7, 1860 public

letter, Brown explained why people like those from whom he sprang would

suffer if the slaves were freed, something he believed the capture of

the White House by a Republican and the resulting Republican-appointed

federal judiciary would bring about within a quarter of a century. If,

he wrote, as had been true in Great Britain when its slaves were freed,

slave owners were compensated for the loss of their slaves as he, who by

then owned a few slaves, believed was fair, non-slave owners would have

to pay high taxes to raise the necessary funds. This would be true even

if, as was unlikely, Northerners agreed to bear part of the cost. Like

many Southerners, he did not think whites and blacks could peacefully

co-exist in the absence of slavery; so he thought sending them to Africa

was a good idea. However, the cost of financing their transportation;

the acquisition of land for them there; and supporting them until they

could get established would significantly further increase the tax

burden on non-slave owners.

If they were not sent to Africa,

they would remain in the South because some of the Northern States had

already passed laws prohibiting free blacks from settling in them. Even

if slave owners were not compensated for the loss of their slaves, and

the slaves were not returned to Africa, non-slave owners would suffer

economic harm. This was because money that still relatively wealthy

Southerners would previously have invested in slaves would, instead, be

used to buy land. They would soon buy all the lands in the South worth

cultivating. Then poor whites would all become tenants like they were in

England, the New England States, and in the other old countries where

slavery did not exist. The freed slaves, too, would become tenants, and

they would have to begin life as free men miserably poor, with neither

land, money nor provisions. They must, therefore, become day laborers

for their old masters and come into competition with poor white

laborers. This competition between blacks and whites would, he believed,

reduce whites' wages. Because abolitionism was an attack on property

rights, he warned Georgia's non-slave owners that they should not sit

idly by and allow other people's slave property to be taken from them.

According to some historians,

Brown's forecast of a non-slave future was pretty accurate. Economic

historian Gavin Wright, for example, observes that, while before the War

the South was not a low wage region, afterwards, for the unskilled, it

was, and unskilled whites' wages were depressed almost to the level of

those paid blacks. Slave owners who, he says, before the War sought to

maximize the value of the output of their slave workers, and, therefore,

their value, after the War became landlords desiring to maximize the

value of the output of their land.

Fortunately for Brown, it was not

known until long after his death that in order to obtain his release

after the War, he agreed to induce Georgians to be loyal to the U.S.

However, it appears that there was no dishonesty involved in his making

this promise, as it seems that, ever the realist, he believed what he

preached. He explained joining the Republican Party after the War by

observing that "We may offer resistance, or refuse to act, for years to

come, and live under military government, or in a state of anarchy, and

we will still be compelled, in the end to come to the terms dictated by

the conqueror. Then why delay longer? "To continue to pay taxes and be

dominated by a government in which you had no representation was," he

believed, "unthinkable.

During the last decades of his

life Brown was one of Georgia's three most powerful politicians. The

other members of the Bourbon Triumvirate were fellow Atlantans Alfred H.

Colquitt and John B. Gordon. Though from a more prosperous family than

Joe Brown, John Brown Gordon (no relation) was also a lawyer; from the

same part of the State; and owned coal mines there that by 1860 had made

him financially secure. Unlike Brown, this fearless General was

handsome, a fine orator; and a natural-born leader of men; yet he was

much less successful as a businessman. After the War, Gordon was elected

governor and to the U.S. Senate. (Today there is a Gordon County in

Georgia, but there is no Brown County.)

How Brown solved some of his

political problems is revealed by the advice he gave his carpetbagger

partner Hannibal Kimball regarding how he might get the State of Georgia

to honor the "Bullock bonds," bonds issued during the administration of

carpetbagger governor Rufus Bullock, a one-time ally of Brown. Kimball

should, Brown said, obtain funds sufficient to control the important

newspapers, conciliate the politicians most popular with the people, and

hire lobbyists. While Brown often resorted to such use of the "carrot,"

he sometimes resorted to the stick. To silence one newspaper editor he

forced the liquidation of the newspaper by having a bank in which he was

a major stockholder foreclose on a loan to the editor.

Brown gained the seat in the U.S.

Senate earlier denied him by the voters of Georgia when General John B.

Gordon gave up his seat in order to accept a $14,000 a year position

with the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N) Governor Alfred

Colquitt appointed Brown to the U.S. Senate seat vacated by General

Gordon, and both Brown and Gordon agreed to support Colquitt for

reelection. Because many believed Brown had paid off Gordon in order to

get his seat, they were subject to an avalanche of criticism.

Brown made money through trading

before he became governor, while he was governor, and thereafter. He

made money during the war trading in bonds, especially railroad bonds,

and lending the State money. He was the president of and owned stock in

the company that leased the State-owned railroad, the Western and

Atlantic (W&A). This business fit like a hand in a glove with his

extensive interests in coal and iron mining in the Northwestern Georgia

served by the W&A because he used it to transport his iron and coal, and

it used his coal. He also owned stock in a sleeping car company, the

Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, the East Tennessee Railroad, the

Virginia Railroad, and the Texas and Pacific Railroad. He was also a

major stockholder in Georgia's Citizens Bank.

He began practicing law in Atlanta

in 1866, and his services were soon in greater demand than any other

lawyer in the State. None charged higher fees than he did. In 1866, he

was retained as counsel for four Augusta banks for a fee of $5,000, and

he and the president of a Macon bank agreed to be informers for the U.S.

Treasury in exchange for 25 percent of any money it recovered. In 1867,

he contracted to defend a bank for $9,000.

As of April 1, 1866, he owned

6,818 acres of land in plots scattered around the State. To this he soon

began adding Atlanta real estate. At that time most of his investments

were in farm land and Atlanta real estate. Tax returns for 1872 reveal

that he valued his Fulton County investments at $114,000 ($70,000 in

Atlanta real estate and $25,000 in stocks and bonds). He owned 1,696

acres of land in Cherokee County; 1,520 in Gordon County, and 1,708

acres in eight other counties. In addition, he owned coal- and

iron-bearing land in Bartow, Cherokee, and Dade counties. He also owned

28,000 acres of land in Texas that he had traded his stock in the Texas

and Pacific Railroad for.

When he was governor, Brown said

he would be willing to lease the State owned and operated Western and

Atlantic Railroad for $25,000 a month. By late 1870 the public outcry

against graft in the Western & Atlantic was so loud and insistent that

the idea of leasing the road received support from both major parties.

The Democrat who introduced in the General Assembly a bill to lease the

W&A asked Brown, who was then Chief Justice of Georgia's Supreme Court,

to put the finishing touches to the bill.

A group headed by Brown and

Kimball submitted a bid, and although their bid of $25,000, the minimum

allowed, was not the low bid, they got the lease. Their group merged

with one of the two other bidding groups, one of whose members got a

large payment from Brown for unspecified services. ("I have made it a

rule as a lawyer," Brown wrote, "to law for other people who desired it

and compromise for myself."

Like Gordon, at his mines Brown

worked convict labor leased from the State. Public protest against the

lease system resulted in four investigations of convict camps.

Investigating committees consistently gave Brown the best report.

Presumably, Brown did not hurt his cause by giving investigators free

transportation on the W&A and hosting a dinner for them

In 1887, in a debate about a

proposed amendment to the Constitution he opposed that would prevent a

state from denying the right to vote on the basis of sex, he denied that

suffrage would raise women's pay because wages are determined by supply

and demand, and being able to vote would not supply women with more

strength and ability.

In a speech he made on the floor

of the Senate on March 27, 1882 on a tariff bill, Brown revealed that he

was opposed to direct (internal) taxes because, unlike a tariff, they

were not progressive. Tariffs on imports are progressive in nature, he

said, because the wealthy consume a disproportionate share of imports;

while the burden of that day's direct taxes levied a more equal burden

on the public. He advocated the elimination of direct taxes because they

were not progressive. Only in time of war did he think it was right to

levy them. Although he said in this speech that the federal government

should spend less, in the Senate he fought hard to direct federal funds

to Georgia; disproportionately in the case of education because Georgia,

like the other Southern States, lagged behind the rest of the nation.

Even though the intent in levying a tariff is to raise revenue, he

pointed out, it will serve to protect domestic producers of the product

the tariff is levied on; so there is no such thing as a purely revenue

tariff.

"I am," he declared, "neither a

free-trade man, willing to collect all the money we have to raise by

direct tax upon the people, nor am I willing to lay a tax simply for

protection when the Government does not need the money. But if I had it

in my power I would raise all the money necessary to support the

Government by tariff, and I would so adjust the tariff which we have to

raise to meet the necessary expenses of the Government as to afford as

far as possible an incidental protection to home industry...." He was

also a supporter of a return to a bimetallic (gold and silver) monetary

standard.

Brown retired from the Senate

before his death in 1894. By then most Georgians had forgiven him for

turning Republican after the War. According to the author of a history

of Cherokee County, "It was Brown's gift for expediency that caused him

to fall into popular disfavor when the war and his last term as governor

were over. Foreseeing the era of the carpetbaggers, he aligned himself

with the Republican party and advocated submission to the victorious

North. That he was able by this policy to make reconstruction easier for

Georgia is now undisputed, but his about-face won him much contemporary

bitterness."

Thanks to

Richard Brown for the above. |

Return to B Index

Return to Mini Bios Index |