|

Death Notice and Obituary of Colonel Joseph Brown of Maury Co. and

Giles Co., TN

Nashville Republican Banner,

Feb. 6, 1868:

We heard it reported yesterday that the veteran pioneer and Indian

fighter Col. Joseph Brown of Giles County died during the morning at

the advanced age of 96 years.

Pulaski Citizen, Pulaski, Tennessee, Feb. 8, 1868:

Died in this county Feb. 4,

1868, Col. Joseph Brown aged 95 years, 6 months and 2 days. Col.

Brown immigrated with his father's family Col. James Brown a

Revolutionary officer in the North Carolina line to Tennessee in

1788. His father and brothers were massacred by the Indians in that

year. Together with his mother and several sisters and he [,they

were] captured and held in captivity for a long time. He died on the

58th anniversary of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, of which he

was one of the founders, and was a professed Christian for 80 years.

He held the first prayer meeting that was ever held in Maury County,

to which he invited in person, every white inhabitant of the county.

It is impossible to portray in a brief notice the many noble traits

that adorned the character of the deceased, or to give anything like

a synopsis of the many daring adventures in the service of his

country."

Note:

From: MaryHul@aol.com

A xerox copy of the original letter furnished by Mrs. Evelyn

McAnally, Columbus, TN. The original letter is in the Joseph Emerson

Brown Papers, The University Library, Univ. of Georgia, Special

Collections, Athens, GA.The letter was

addressed to Joseph E. Brown, Milledgeville, GA. Giles County,

Tennessee, April 26th 1859.

Honerd Friend

I received yous of the 16th

instant and was much gratefyed to hear of your health and the

welfare of your family. I am still in the Enjoyment of good health

at preasent but met with a serious deficulty on the 12th of August

last. being ould and stiff in going out of the door my shew hung on

the Upper step and I pitced forward on a stone pavemant and my right

hench bone struck the kirbing of the pavement and dislocated the

they and mashed me so that I was confined to the house for ten

weaks. but have Recovered so that I can Creap a bout with onley a

staff, and if not deceived I fell thankful to my Grate Creator for

his maney merceys to so unprofitabel a servant as I have been.

My Daughter whome I live with

and my children in Texas and Mississippie are all in their Common

health as Enquires.

My Fathers name was James

Brown and he was the third son of William Brown and as you wish to

know aboute your ancestrey I can give it f (for) a hunrd and fifty

years

Your Great Great Grand Mother

which was my Grand Mother, her maiden name was Margaret Fleming

commonly called Peggy she married William Brown and lived in the

north of Ireland and so near Londarey that she could hear the Bels a

toling in the Cittey from the (their) own house.

Father: James BROWN b: BET. JAN 1719/20 - 1733 in

Ireland

Mother: Jane GILLESPIE b: 22 JUN 1740 in PA

They settled in the

Cumberland. Joseph became a ordained Methodist? Minister after

serving in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. Mother Jane

never remarried.

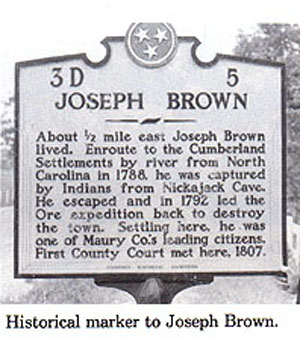

THE JOSEPH BROWN STORY:

PIONEER AND INDIAN IN TENNESSEE HISTORY

By C. Somers Miller

The central theme of Tennessee

history before 1794 was the struggle of the pioneer to wrest his own

survival from a hostile wilderness. Historians have not failed to

note that this struggle very often took the form of a series of

bloody incidents on the frontier between pioneer and Indian.

One of the most often recorded

episodes of the frontier was that of Joseph Brown, immigrant to the

old Southwest in 1788. Captured by the Cherokees, he was later

released but returned to pilot an expedition to destroy the Indians'

Five Lower Towns where he had been held prisoner. He finally settled

in Maury County, Tennessee, where he lived until his death in 1868.

His longevity and eagerness to tell of his experiences rewarded

nineteenth century historians who sought from him a description of

life on the Southern frontier. His story became one of the most

often repeated episodes in Tennessee history of this period.

In attempting to tell the

Joseph Brown "story," historians have described the character of the

pioneer and the Indian. This paper will examine several accounts of

the Joseph Brown "story" written in the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries. It is my thesis that the frontier character has not

remained a static concept but has, through the years, been

interpreted in at least three different ways, and further that the

narratives reflect the constant esteem of the Southern historian for

his region's past.

The Cherokees and the American

settlers in the transmontane area of North Carolina were the cause

of much concern during the Revolutionary War. American revolutionary

leaders worried that Indian presence in this area might hamper trade

with New Orleans and block communication with American posts on the

Mississippi and Ohio. The frontier settlements of Watauga,

Nolichucky, and on the Holston were considered by the British to be

in violation of the Proclamation Line of 1763, which forbade

colonists to settle west of the Appalachians, and represented a

threat to British authority in the area.

In the competition between the

Americans and the British for the Cherokees' favor, the British were

successful. Hoping to cause the withdrawal of frontier support from

the southern American armies, Lord Cornwallis formulated plans in

1780 for an Indian attack on the settlements. The Cherokees and

Chickamaugas began a number of raids on white settlements which were

countered by expeditions upon the Indians led by John Sevier. The

result was constant strife in that part of the west.

The Treaty of Hopewell,

written in November, 1785, was an attempt to make peace with the

Cherokee and other Indian tribes which had sided with the British.

Although the negotiations defined a boundary between lands of the

Indians and the settlers, efforts at such adjustment came too late:

settlers and land-hungry speculators, following successful treaty

writers, had already spilled over into Indian regions. A boundary

line which divided two peoples became an area of "claims and

counter-claims, of raids and counter-raids, of land occupied in some

places by white and red men alike. It was a frontier of depth and

trouble."

Sevier's expeditions against

the Cherokees, though highly praised by some historians, made

pioneer life more troublesome. A large band of belligerent Cherokees

had been forced southward down the Tennessee River where they joined

a smaller group of Chickamaugas. Living in a number of villages

clustered around the Tennessee, known as the Five Lower Towns, and

located not far from present-day Chattanooga, they were soon

strengthened in their mountain bastion by the addition of groups

from the Creek and Shawnee tribes. This location made matters worse

for the settlers because the Five Towns were the center of Indian

water communications and near the Great Indian Warpath which

connected them with allies to the south in Georgia and with those as

far north as Detroit. Even worse, other trails leading northward

enabled the Cherokees to strike at newly settled areas along the

Cumberland River. The Indians, strengthened in numbers, had found a

strategic location to launch attacks against any intruding whites.

North Carolina was faced with

a moral and legal obligation to reward soldiers of the Continental

line and militia who had served during the Revolution. As the state

treasury was empty, the solution to this problem seemed to lie in

the abundance of western lands across the mountains, which could be

granted,, with little expense to the state, to North Carolina's

Revolutionary veterans.

Living in the rolling piedmont

section of that state was Colonel James Brown who had immigrated to

the colonies from Ireland and purchased a small land holding at the

head of the Yadkin River. He had been married to Jane Gillespie

Brown for several years when, with a growing family, he relocated in

Guilford County. After a short time, he was chosen a magistrate of

that county, served as High Sheriff and as a ruling elder of the

Presbyterian church.

The Revolution had come to

Guilford Court House in March 1781. Brown, a soldier in the

Continental line, was engaged in the battle under Colonels Lee and

Washington which resulted in a tactical victory for the Americans.

Thus, when North Carolina in 1785 offered payment of Revolutionary

soldiers' claims in western lands, James Brown took advantage of the

opportunity and located his military warrant on the Cumberland and

Duck Rivers.

Shortly thereafter he took two

of his older sons, explored the Cumberland valley, and entered large

claims for additional lands. Choosing a tract for settlement about

five miles below Nashville, he returned for his family in North

Carolina, leaving the two sons to build a cabin and clear the land

for cultivation.

During the winter of

1786-1787, he built a large boat on the Holston to transport his

family down the Tennessee and up the Ohio and Cumberland Rivers to

Nashville. The boat was well constructed of oak, two inches thick,

and upon its stern Brown mounted a small cannon. He took on board a

cargo of useful goods and embarked from the Long Island of the

Holston on May 4, 1787, with a party of himself, his wife, two sons

who were grown; Joseph, aged fifteen; a younger son, George; and

three daughters, Jane, ten, Elizabeth, seven, and Polly, four. There

were, in addition to Brown's family, five young men and several of

the family's Negro slaves aboard.

About daybreak of May 9, as

they passed a Cherokee village on the lower Tennessee, a canoe

approached their boat. It was filled with Indians who hailed the

settlers and appeared so friendly that they were permitted to come

on board. Their headman Cutleotoy, professed friendship and was

kindly treated. Shortly thereafter the Indians returned to their

town and immediately sent runners to Nickajack and Running Water

villages down river, to raise a group of warriors to intercept the

boat.

A party of forty Indians led

by the half-breed John Vann, who spoke English, met Brown's boat

before it reached Nickajack. Vann also pleaded friendship citing the

Treaty of Hopewell and was successful in boarding under the pretense

of wanting to trade. Once Vann had accomplished his first stratagem,

seven or eight other canoes appeared. Despite Brown's protests, more

Cherokees came on board and began scuttling the boat. In the ensuing

melee, the Indians gained control and Colonel Brown was killed by a

Cherokee warrior.

Once the Indians had grounded

the boat at Nickajack, they began to expropriate prisoners. A group

of Creeks who had happened to be along, took Mrs. Brown, her

youngest son, George, and her three daughters and hastened to their

towns on the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers. Kiachatalee, of Nickajack,

obtained Joseph Brown and turned him over to Tom Tunbridge, deserter

from the British army, who had established a trading post among the

Cherokees and had married Kiachatalee's mother. As the Indian trader

hurried Joseph off to his home, the boy heard rifle shots coming

from the direction of the river. He soon learned that his two older

brothers and the five other men had been ambushed and killed by the

Cherokees.

In the meantime, the Indians

of Nickajack had come to believe that they had been cheated of some

of their captives by the Creeks. Warriors were dispatched to catch

up with the Creek party. When they were intercepted, two of the

Brown daughters were returned to Nickajack.

After Joseph Brown arrived at

Tunbridge's house, an old Indian woman came in and angrily scolded

the trader for having brought the boy away from Nickajack, and

thereby preventing his being killed along with others. She warned

that Brown would later pilot an army there to kill them all. Shortly

after she had gone, Cutleotoy with a group of braves approached

Tunbridge and asked that the boy be released to them so that they

might kill him. The Englishmen resisted the Indians' demand, saying

that Joseph Brown was Kiachatalee's prisoner and that his step-son

would be sure to revenge the boy's death. Finally, after Cutleotoy

threatened Tunbridge with a drawn knife, the boy was turned over to

them.

Brown was taken to a place a

short distance away where it appeared that he was to be killed.

Being a religious young man and as death was certain, he asked for

some time to pray. Joseph knelt and prayed the prayer of St.

Stephen, trying to give his soul to God. He remembered the

experience of St. Stephen: how the saint when he was stoned, saw the

heavens open, revealing Christ at the right hand of God. At this

point, Brown's eyes opened involuntarily and he saw smiles upon the

Indians' faces. Later Joseph learned that Cutleotoy had decided

against killing him because the Indian highly valued the Negro slave

he had obtained from the division of the Brown property, and feared

that Kiachatalee might kill the slave in revenge for Joseph Brown's

death.

The boy's life had been spared

and soon he was taken into an Indian family and began to adopt their

ways of life. Joseph wore the breech cloth and the short shirt, and

his head was shaved, leaving a scalp lock. He even developed a

relationship of respect and affection with his captors, Kiachatalee

and the Tunbridges. He lived with the Cherokees for almost a year

during which time he became acquainted with the territory around

Nickajack and the other Five Lower Towns.

Warfare between the Indians

and settlers continued on the frontier. An expedition under Colonel

Joseph Martin came near Nickajack but was repulsed by the Indians.

During the winter of 1788-1789, General Sevier followed a large body

of Cherokees to a town on the Coosa River where he took about

forty-five prisoners and returned with them to the white

settlements. Sevier proposed a prisoner exchange with the Indians

and it was in this way that Joseph and his two sisters were released

from captivity in April, 1789.

Brown and his sisters made

their way back across the mountain to an uncle's home in the

Pendleton District of South Carolina. There they waited for some

news of the condition of Mrs. Brown, their sister Elizabeth and

brother George. About six months after Sevier's exchange, Mrs. Brown

and Elizabeth were taken to Rock Landing, Georgia, and restored to

their family through the efforts of the Creek chief, Colonel

Alexander McGillivray. George Brown was to remain with the Creeks

until October, 1793..

The reunited family remained

in South Carolina for almost a year. In the fall of 1790, gathering

together their belongings, they again headed for the Cumberland

settlements. This time they chose the overland route to their

property south of Nashville. Upon arrival, they began farming in

spite of constant threats of Indian massacre. Joseph Brown, now

considered a grown man, was often employed as a post rider between

the Cumberland settlements and Knoxville. In this capacity he was

often exposed to Indian attack and several times narrowly escaped

death or capture. He began to regard himself as an Indian fighter

and participated in an expedition against the Cherokee.

In 1794 Brown volunteered to

serve under Major James Ore in a campaign that was to destroy the

Cherokee base at Nickajack. He piloted the volunteers across the

mountains and while the rest of the men circled the village, Brown,

being familiar with area, led twenty men to another position to

insure that no Indian would escape after the battle began. The

frontiersmen completely surprised the Indians and killed or captured

about one hundred Cherokees. Brown later reported that he had been

in the midst of the fighting, had nearly scalped one Indian and had

taken a squaw prisoner. He believed that he had fulfilled the

earlier prophecy of the old Cherokee woman: he had piloted an army

there to destroy them. The victory over the Cherokees in 1794 ended

the Indian menace from the Five Lower Towns.

Joseph Brown returned to his

new wife and his home on the Cumberland where his first son was born

in 1795. The same year he was engaged as a spy and guard at Fort

Blount. Brown had a personal interest in seeing that the Indian

threat was diminished on the Tennessee frontier; he still possessed

title to a large acreage along the Duck River which had been granted

his father.

In 1805 he decided that

conditions were safe enough to move his family across the Duck into

what is today Maury County where he came to play an active role in

the county's history. Brown and his brother-in-law, Benjamin Thomas,

became the first white inhabitants of that area. Brown constructed a

house in which the first county court was held in 1807, and was one

of the commissioners to establish the town of Columbia. In this town

he began to acquire property and by May, 1811, owned more than

fifteen hundred acres. That Brown had become a man of some standing

in Maury County is indicated by the inscription of "Esquire" beside

his name in county records.

During the Creek War of

1813-1814, he was elected a colonel and served under General Andrew

Jackson for four months, participating in the battles of

Tallahatchee and Talledega. In the latter engagement he and his

command were thrown into battle against five hundred Indians.

Seventy Indians were killed and the Tennessee troops emerged

victorious. From his engagements at these battles, a curious story

has found its way into some histories of this man. It was written

that at the battle of Talledega, Brown learned from an Indian that

Cutleotoy was still alive and had possession of several Negroes who

were descendants of the slave taken from the Brown family in 1788.

Investigation indicates that as early as October, 1811, Brown was

aware that the slaves were within three days' traveling distance of

his home in Maury County.

Colonel Brown forcibly

recovered some of these slaves from Cutleotoy at Fort Hampton in

January, 1814, and in so doing he violated a treaty made between the

United States government and the Cherokees. The Treaty of Tellico of

1798 had bound the United States to protect the Cherokees against

any claims arising from Indian thefts or plunderings which occurred

before the date of the treaty Legally, Brown was barred from

recovering any of the Negroes and he could have been subjected to

damages resulting from this act.

After the Creek Wars Brown

returned to Maury County, never again to participate in Indian

expeditions. Interviewed in 1852, he stated that he had since 1815

led a peaceful life. Perhaps this was a correct description from

someone who had undergone Indian captivity and had been involved in

numerous campaigns. Records indicate that the rest of his life may

have been peaceful but that the tranquillity was definitely

interrupted from time to time. Between 1817 and 1821 he was sued

several times in cases before the Maury County Circuit Court.

Shortly after he appeared as a defendant in court, he volunteered

his services to go to Washington to collect claims for property lost

in the Seminole War.

Some of the peacefulness to

which he referred may have been derived from his acceptance of

ministerial duties for the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in

Columbia. Yet it would be difficult to describe the religion he

practiced as entirely tranquil. Someone who viewed Brown's religious

experiences in the 1820's described them for a later audience:

About 1822, when a small boy,

I attended a camp-meeting at McClain's. Only a few tents were then

built; some camped in covered wagons...Among the tents built, was

the one so long occupied by Co. Brown, and there I first saw him

under religious excitement, and first heard that involuntary "Oh!'

accompanied by the spasmodic jerk, forward and downward, and as he

arose erect, "My Redeemer!" was uttered in a low voice. Those who

once heard him, can recollect the effects and intonations of his

voice....."

As Brown grew older, his

religious zeal increased, an enthusiasm probably accentuated by the

growing prevalence of fundamentalism in rural Tennessee. In any

case, his letters and interviews reveal a man who came more and more

under religious influences. That this tendency was also reflected by

his biographers will be shown later.

There developed during the

1850's a growing interest in Tennessee history, perhaps attributable

to the reorganization of the Tennessee Historical Society in

Nashville in 1849, which was incorporated the following year by the

state legislature. Although this organization received little

popular support and its meetings were few, a handful of men, mostly

Nashville residents, attempted to stimulate interest in the state's

history and desired to preserve papers and artifacts which might be

revealing of the state's past.

One of the first members of

the society was William Wales, of Nashville, who in 1852 began

publishing the South-Western Monthly, a literary magazine. Wales had

been inspired by the organizations' founding and in an extended

editorial he urged his reader's to take an interest in Tennessee

history and chided them for their wavering support of the historical

society's work. Tennessee had a "glorious train of events for

contemplation;;" in its history were stories of fabulous romance. To

preserve these "mementos of the past, " the public should cooperate

with the society. Other states had given generous support to their

organizations and libraries; Wales regretted that Tennessee had done

very little to record her greatness.

The same editorial entreated

its readers to learn from the "patriarchal few who might acquaint"

them with a time when the state was an unbroken wilderness.

Apparently, Wales had followed his own advice and traveled to Maury

County to write a sketch of the aging Joseph Brown. It is probable

that he was accompanied on this interview by Feliz K. Zollicoffer

who in 1850 had taken charge of the Nashville Banner. Zollicoffer

would have been well acquainted with Brown, for he was a Maury

County native and had been publisher and editor of the Columbia

Observer before moving to Nashville. In his ANNALS OF TENNESSEE,

published in 1853, James G. M. Ramsey printed Brown's narrative

which was supplied by Zollicoffer. A comparison of Ramsey's account

and that published in the South-Western Monthly reveal so many

similarities that it is evident Zollicoffer and Wales must have

combined efforts.

The narrative in Wales'

quarterly portrayed the story of the brave pioneer who unflinchingly

endured dangers to migrate to a new territory. It mattered not at

all that the Indian had an older right to the land; rather, it was

the duty of the pioneer to open this land for settlement. The savage

was a definite obstacle that must be overcome. If this obstacle

threatened the white settler, he must be punished or killed.

Brave and conscious of his

duty, Joseph Brown personified the pioneer. He had come to Tennessee

as a youth, and experienced numerous hardships in Indian captivity.

After his release from the Indians, he returned to Tennessee to

insure the safety of its frontier society against the defiant

savage. He was a man to whom the United States owed gratitude for

its first step in civilization. Brown, the gallant pioneer, became a

hero in Tennessee history. Wales accomplished what he had set out to

do; he had recorded the exploits of Joseph Brown so that they would

not "moulder in oblivion.." Now well over one hundred years old, the

narrative in the South-Western Monthly remains one of the most

detailed accounts of the Indian exploits of Joseph Brown.

The same year that Wales began

publication of his literary magazine, Mrs. Elizabeth Ellet wrote

PIONEER WOMEN OF THE WEST. Directed to a national audience and

published in New York, her book contained numerous sketches of

frontier women, one of these being Mrs. James Brown.

Mrs. Ellet, born in the

western part of New York in 1818, was the daughter of a pioneer of

the section, William Nixion Lummis. At the age of fifteen she

married Dr. William H. Ellet, a professor of chemistry at Columbia

College, New York City. The same year as their marriage, Dr. Ellet

accepted a position at South Carolina College where they remained

until 1849, when they returned to New York. Mrs. Ellet developed an

interest in history and published hundreds of essays, shot stories,

and sketches during her life time. Her PIONEER WOMEN is not well

documented but she acknowledged assistance from Milton A. Haynes of

Nashville and her use of valuable manuscripts belonging to a

historical society of Tennessee.

Mrs. James Brown's story

differed in at least one respect from the narrative published by

Wales' Ellet and included the story of Brown's recovery of the Negro

slaves. After the Battles of Talledega, the Indian fighter learned

that Cutleotoy was still living and had with him the descendants of

the slaves taken from the Brown family in 1788. Joseph Brown

proceeded to the Indian village and obtained his rightful property.

Describing the episode, Ellet portrayed Cutleotoy as a criminal

deserving death and Brown as the ideal Christian who was able to

repress his feelings of revenge for his father's death. The Cherokee

was presented as a criminal race "whose blood thirsty natures panted

for the blood of the white man," a lawless people who deserved death

in the Nickajack campaign.

Ellet believed

that by telling the story of Mrs. Brown, the condition, progress,

and character of a people would be better illustrated. The tale had

all the characteristics of a romance but it was a "plain sad story

of trials and sufferings" incident to the period and border life.

The sadness and suffering of those hardy and wise pioneers was

inspiring because, despite adversities, they had been able to

construct a state in the midst of Indian warfare. The recurrent

theme in Ellet's history was the perseverance of the pioneer. The

world of the frontier woman was one of "vexation and sorrow," but

she endured the hardships of frontier life and experienced the loss

of husband and sons killed by Indians.

|

Thanks to

Richard Brown for the above. |