|

Bonnie Prince Charlie

A quarter of a century

elapsed before the sword was again drawn, for the

last time, in the cause of the Stuarts. No event

in Scottish history has been the subject of deeper

or more enduring interest than the rising of 1745.

It is full of incidents of personal daring and

romantic adventure, and it has all the pathetic

interest which attaches to the last struggle of a

lost cause. In more ways than one it was, like the

Union, the “end of an auld sang.” Prince Charlie’s

departure for France ended the history of old

Scotland – the tumultuous and impoverished

Scotland of the Middle Ages – “loitering in the

rear of civilsation,” to use Mr. Froude’s phrase.

Then began the history of modern Scotland, the

prosperous agricultural, manufacturing, and

commercial Scotland in which we live. So vast has

been the change that it is not easy to realize

that the period which has elapsed between the

battle of Culloden and our own day does not exceed

the span of two long lives. [For example, in July

1897 there died in Dundee William Robertson, aged

ninety-seven, who was in early life a servant to

Colonel Alexander Macdonnell of Glengarry. While

in that situation he frequently met and conversed

with Owen Macdonnell, who had fought at

Prestonpans, Falkirk, and Culloden. Owen was then

nearing a hundred years old, and was full of

stories of the campaign. –

Edinburgh Evening Dispatch, July 12, 1897.]

After the failure of

the Spanish expedition of 1719, James Stuart, as

we have seen, returned to Italy. His marriage with

Princess Clementina Sobieska, which has already

been celebrated by proxy, took place at

Montefiascone in Setember 1719. Two sons were the

issue of the marriage, Charles Edward Louis Philip

Casimir, born in 1720, and Henry Benedict Maria

Thomas, born in 1725. The former was the Prince

Charlie of the ’45.

Early in life the heir

of the lost cause showed that he had inherited not

only the personal charm of the Stuarts, but no

small share of the valour and capacity of John

Sobieski. As a lad of fourteen he gave proof of

his courage at the siege of Gaeta. John Walton,

the agent of the English Government at Rome,

speaks with frank admiration of his bravery and

talents. “Everybody,” he writes, “says that he

will be in time a far more dangerous enemy to the

present establishment of the Government of England

than ever his father was.” [State Paper, Tuscany,

Aug. 7, 1734. Walton’s letters are full of

information about the Prince’s youth. See the

extremely interesting early chapters of Mr. A. C.

Ewald’s

Life and Times of Prince Charles Stuart.]

During the years

between 1720 and 1740 the history of Jacobitism is

that of a succession of fruitless intrigues.

Jacobite agents hung about every Court in Europe,

and the little exiled Stuart Court at Rome and

Albano was full of busy plotters, hatching

projects which came to nothing. In Scotland

Lockhart organized a body of “Trustees” to take

charge of James’s interests. This body was

regarded with much jealousy by those who

surrounded James in his exile, and appears never

to have received his formal authorisation. “They

had an opportunity,” says Burton, “for quarrelling

with the Jacobite clergy, and seem only to have

been saved from deeper quarrels with the Court of

Albano because neither body could find anything to

do or to quarrel about.”

In the meantime the

Government was taking such measures as seemed best

calculated to reduce the Highlands to order and

submission. No serious steps were taken to punish

those who had taken part in the affair of 1719; it

was evidently desired that the whole thing should

be allowed to blow over. Two disarming Acts were

passed, but were very imperfectly carried into

effect. Naturally, they were but obeyed by the

clans which were in the interest of the

Government. The disaffected clans gave up large

quantities of worthless arms – it was said that

some were imported from abroad for the purpose –

but, as afterwards appeared, they retained an

ample supply of efficient weapons. The chief

result of the Acts was to deprive the Government

of such assistance as they might have received on

emergency from the Campbells and other Whig

clans.

At the same time was

begun the enterprise of opening up the Highlands

by the great system of roads which is associated

with the name of General Wade. The main roads

actually constructed by Wade himself were (I) the

great Highland Road, which goes by Dunkeld and

Blair Atholl to Inverness, familiar to all

travelers by the Highland Railway; (2) a road

running from Stirling to Crieff, through Glen

Almond, past Loch Tay, and so north to join the

Highland road at Dalnacardoch; and (3) a road from

Inverness to Fort William, along what is now the

line of the Caledonian Canal. This last road was

connected with the Highland Road by a branch

passing over Corryarrack. As we shall see, this

branch was, for military purposes, or more use to

the Jacobites that it ever was to the Government.

Since the beginning of

the eighteenth century a number of independent

Highland companies had been maintained as a kind

of police force in the service of the Government.

It was Duncan Forbes of Culloden, Lord President

of the Court of Session, one of the wisest and

most patriotic of Scottish statesmen, who first

suggested the idea of utilising the dangerous

warlike spirit of the clans by raising Highland

regiments for foreign service. The Forty-third

Regiment, afterwards the Forty-second, was

embodied in Strathtay in May of 1740. It inherited

from the old independent companies their name of

the Black Watch, which it has since made

illustrious throughout the world.

In 1739, much against

his will, Walpole declared war against Spain. It

seemed to the Scottish Jacobites that war with

France was inevitable, and that their opportunity

was come at last. In the beginning of 1740 some of

their leaders met at Edinburgh and framed an

“Association” engaging themselves to take arms and

venture their lives and fortunes to restore the

family of Stuart, provided that the King of France

would send over a body of troops to their

assistance. This document was signed by Lord

Lovat, James Drummond, titular Duke of Perth, Lord

Traquair, Sir James Cambell of Auchinbreck,

Cameron of Lochiel, John Stewart, brother of Lord

Traquair, and Lord John Drummond, and was

entrusted to Drummond of Balhaldy to be carried to

Rome. The French Court was approached, and was

lavish in its promises of aid. Cardinal Tencin,

who, on the death of Cardinal Fleury in January

1743, became Prime Minister to Louis XV., was

actively friendly to the Stuart cause. John Murray

of Broughton, who had now been constituted James’s

Secretary for Scottish affairs, was sent to Paris

to arrange the details of an invasion of Great

Britain. It was ultimately arranged that 3000

French troops should be sent to Scotland under the

Earl Marischal, while 12,000 under Marshal Saxe

were to be landed in England and to march to

London. Murray then proceeded to Scotland to

prepare the Jacobite clans to support the

projected invasion. The troops were assembled at

Dunkirk; a fleet was prepared at Brest and

Rochefort; and Prince Charles, with his father’s

permission, came to France to accompany the

expedition. “I go, Sire,” said he at parting with

James, “ in search of three crowns, which I doubt

not but to have the honour and happiness of laying

at your Majesty’s feet. If I fail in the attempt

your next sight of me shall be in my coffin.”

“Heaven forbid,” answered James, bursting into

tears, “that all the crowns of the world should

rob me of my son. Be careful of yourself, my dear

Prince, for my sake, and I hope for the sake of

millions.”

Charles reached Paris

on January 20, 1744, and the expedition was at

once put into motion. The British Government were

greatly alarmed, as the greater part of their

troops were in Flanders, the fleet was in the

Mediterranean, and there were only six ships of

the line ready at Spithead. However, the

expedition was attended with the usual ill-luck of

all Jacobite enterprises. Its fate is thus

described by Home in his

History of the Rebellion: “Orders were

immediately given to fit out and man all the ships

of war in the different ports of the Channel;

never were orders better obeyed, for the French

fleet having been driven down the Channel by a

strong gale of easterly wind, before they could

get up again Sir John Norris with twenty-one ships

of the line and a good many frigates arrived in

the Downs, where he lay watching the motions of

the transports at Dunkirk from the 16th

to the 23rd of February. That day an

English frigate came into the Downs with the

signal for seeing an enemy’s fleet flying at her

masthead. The English ships unmoored and, having

the tide with them, beat down the Channel against

a fresh gale of westerly wind; at four in the

afternoon the English fleet caught sight of the

French ships lying at anchor near Dungeness, but

as the tide was spent they also were obliged to

come to anchor. While the two fleets were in this

position, Marshal Saxe, who with the young

Pretender had come to Dunkirk that very day, was

embarking his troops as fast as possible. In the

evening the wind changed to the east and blew a

storm. The French ships, sensible of their

inferiority, as soon as it was dark cut their

cables and ran down the Channel. During the night

all the ships of the English fleet, two excepted,

parted their cables and drove. Both the fleets

were far enough from Dunkirk, and if the weather

had been moderate Marshal Saxe might have reached

England before Sir John Norris could have returned

to the Downs; but when the storm rose it stopped

embarkation, several transports were wrecked, a

good many soldiers and seamen perished, and a

great quantity of war-like stores was lost; the

English fleet returned to the Downs and the French

troops were withdrawn from the coast.”

This attempt to invade

Britain was followed by the formal declaration of

war with France. Charles, deeply mortified by the

failure of the enterprise, retired to Gravelines,

where he lived incognito during the summer of 1744

awaiting events. In the beginning of the following

winter he went to Paris, but found the French

Government not disposed to renew the attempt at

invasion.

The defeat of the

British army at Fontenoy in May 1745 at last

decided Charles to carry out a project which had

long been forming in his mind, namely, to wait no

longer for foreign aid, but to come to Scotland

himself, to throw himself upon the loyalty of his

own people, and with their help to make an attempt

to recover the crown of his fathers. Charles’s

project was not communicated by him to the French

Government; whether they knew of it or not they

gave it no overt support, but they threw no

obstacle in his way. There were then in Paris two

merchants of Irish descent, named Ruttledge and

Walsh, sons of refugees who had followed the

fortunes of James II. They had obtained from the

French Government an old man-of-war of 60 guns

called the

Elizabeth, and had also purchased a 16 gun

brig, the

Doutelle, which vessels they had equipped

for privateering purposes. These vessels were

placed at the disposal of the Prince. He borrowed

180,000 livres from his bankers, pawned his

jewels, and procured what arms he could – 1500

muskets, 1800 broad-swords, 20 field guns, and

ammunition. These were placed on board the

Elizabeth.

Charles did not

communicate his wild project to his father until

he was on the eve of sailing, and it was too late

to prevent it. “Let what will happen,” he wrote,

“the stroke is struck, and I have taken a firm

resolution to conquer or to die, and stand my

ground as long as I shall have a man remaining

with me.”

On June 22, 1745, he

went on board the

Doutelle at Nantes, accompanied by the

Marquis of Tullibardine, Sir John Macdonald, Ǽneas

Macdonald, Colonel Strickland, Sir Thomas

Sheridan, Captain O’Sulivan, George Kelly, Mr

Buchanan, and Anthony Walsh, the owner of the

ship. On July 4 the

Doutelle was joined at Belleisle by the

Elizabeth, and on the 5th the

expedition finally set sail for Scotland. Four

days after leaving Belleisle the ships were

encountered by an English man-of-war, the

Lion, under Captain Brett, who engaged the

Elizabeth. After six hours of sever

fighting both vessels drew off; the

Elizabeth being so much damaged that she

had to run back into Bret, carrying with her the

bulk of the money, arms, and stores which had been

provided for the expedition. Charles repeatedly

urged Walsh, who was in command of the

Doutelle, to bear down to the aid of the

Elizabeth, but Walsh absolutely refused to

risk the person of the Prince, kept at a distance

from the fight, and after it was over made sail

for Scotland. On July 23 the Prince landed on the

island of Eriska in the Hebrides.

On the day after the

Prince’s landing, Alexander Macdonald of Boisdale,

brother of Macdonald of Clanranald, came to meet

him. When he found upon what errand the Prince and

his companions were come to Scotland, “he did all

he could,” says Ǽneas Macdonald, “to prevail upon

them to return to France without making any

attempt to proceed.” [Narrative,

Lyon in Mourning.] He pointed out to the

Prince the madness of attempting to attack the

Government without foreign support, and implored

him to abandon his enterprise. Charles was

resolute. “If I can only get a hundred good,

stout, honest-hearted fellows to join me,” he

said, “I’ll make a trail of what I can do.” The

result was that Boisdale prevented all

Clanranald’s men that lived in South Uist and the

other islands, to the number of 400 or 500, from

joining the insurrection. The Prince, in the

meantime, sent a messenger to Sir Andrew Macdonald

of Sleat. Ǽneas Macdonald crossed to the mainland

to summon his brother, Macdonald of

Kinlochmoidart.

On the 25th

Charles himself crossed to Lochnanuagh and landed

at Borradale in Arisaig. On the following day

young Clanranald, Glenaladale, and a number of

other chiefs came in, and messengers were sent out

to summon others. The opinion of the chiefs was

unanimous that the enterprise was hopeless, and

that Charles ought to return, but the Prince’s

courage and resolution overcame all objections.

There was no more zealous Jacobite in Scotland

than Cameron of Lochiel, but even he thought that

there was not the least prospect of success. He

determined not to take arms, but came to Borradale

for the purpose of waiting on the Prince. On his

way he called at the house of his brother, John

Cameron of Fassefern. Home, who had the incident

from Fassefern himself, narrates what passed

between the brothers. Fassefern asked Lochiel what

was the matter that had brought him there at so

early an hour? Lochiel told him that the Prince

was landed at Borradale and had sent for him.

Fassefern asked what troops the Prince had brought

with him, what money, what arms. Lochiel answered

that he believed the Prince had bought with him

neither troops, nor money, nor arms, and,

therefore, he was resolved not to be concerned in

the affair, and would do his utmost to prevent

Charles from making a rash attempt. Fassefern

approved his brother’s sentiments, and applauded

his resolution; advising him at the same time not

to go any further on the way to Borradale, but to

come into the house and impart his mind to the

Prince by letter. “No,” said Lochiel, “I ought at

least to wait upon him and give my reasons for

declining to join him, which admit of no reply.”

“Brother,” said Fassefern, “I know you better than

you know yourself. If this Prince once sets his

eyes upon you he will make you do whatever he

pleases.” Fassefern was right. When Lochiel

arrived at Borradale he implored Charles to

abandon his enterprise and return. When Charles

absolutely refused Lochiel then begged him to

remain hid where he was till some of his friends

should meet together and consult what was best to

be done. Charles answered that he was determined

to put all to the hazard. “In a few days,” said

he, “with the few friends I have, I will erect the

royal standard, and proclaim to the people of

Britain that Charles Stuart has come over to claim

the crown of his ancestors, to win it, or to

perish in the attempt. Lochiel, who my father has

often told me was our firmest friend, may stay at

home and learn from the newspapers the fate of his

Prince.” Lochiel yielded. “No,” said he, “I will

share the fate of my Prince, and so shall every

man over whom nature or fortune hath given me any

power.

On Lochiel’s decision

depended the fate of the insurrection. It seems

clear that had he persisted in his refusal to join

the Prince very few other chiefs would have done

so. As it was, his example was followed by all the

Jacobite clans.

It was determined to

raise the standard of insurrection on August 19.

The

Doutelle, having discharged her stores, put

to sea on the 4th. On the 11th

the Prince went by sea to Kinlochmoidart; there he

remained to the 17th. In the meantime

the first blow had been struck. An English officer

named Captain Switenham, when on his way to take

command at Fort-William, was taken prisoner on the

14th; and two days later two companies

of the Royal Scots, who were on the march from

Perth to Fort-William, were attacked on the shores

of Loch Lochy by a force under Macdonald of

Tiendrish and made prisoners. On the 19th

the Prince went from Kinlochmoidart to Glenfinnan,

and there the standard of King James VIII. was

unfurled by the Marquis of Tullibardine. In the

course of the day the standard was joined by

Lochiel at the head of seven or eight hundred men,

and by Macdonald of Keppoch with about 300. The

Prince remained till the 22nd at

Kinlochiel, thence he marched by Fassefern, Moy,

and Letterfinlay to Invergarry Castle, which he

reached on the 26th. There he was

joined by Ardshiel with 260 men of the Stewarts of

Appin. Murray of Broughton, the Judas of the

cause, had joined the Prince on the 18th

at Kinlochmoidart. On the 25th he was

appointed secretary. On the 26th, at

Invergarry, a document was drawn up and signed by

all the chiefs present, pledging themselves not to

lay down their arms or make peace separately

without consent of the whole.

In the meantime the

authorities were not idle. To the Government

Charles’s landing had come as a bolt from the

blue. The first rumour of it which had reached

them was contained in a letter written by Lord

President Forbes to Henry Pelham, the Prime

Minister, on August 2.

Sir John Cope, then

commanding the troops in Scotland, is described by

Home as “one of those ordinary men who are fitter

for anything than the chief command in war,

especially when opposed, as he was, to a new and

uncommon enemy.” His incapacity to deal with the

terrible emergency with which he was confronted

has earned for him an immortality of ridicule,

perhaps not altogether deserved. The troops which

were at his disposal at the outbreak of the

insurrection were thus described by himself at the

inquiry into his conduct which subsequently took

place. “As much as I can remember on the 2nd

of July the troops in Scotland were quartered

thus: -

“Gardener’s Dragoons

at Stirling, Linlithgow, Musselburgh, Kelso, and

Coldstream.

“Hamilton’s ditto at Haddington, Dunse, and the

adjacent Places.

“N. B. – Both Regiment at grass.

“Guise’s Regiment of Foot at Aberdeen and the

Coast-Quarters.

“Five Companies of Lee’s at Dumfries, Stranraer,

Glasgow, and Stirling.

“Murray’s in the Highland Barracks.

“Lascells’s at Edenburgh and Leith.

“Two additional Companies of the Royal at Perth.

“Two ditto of the Scotch Fuziliers at Glasgow.

“Two ditto of Lord Semple’s at Cupar in Fife.

“Three ditto of Lord John Murray’s Highland

Regiment at Crieff.

“Lord Loudon’s Regiment was beginning to be

raised; and, besides these, there were the

Standing garrisons of invalids in the

Castles.

“N. B. – As to the

additional Companies of the Royal, Scotch

Fuziliers, and Semple’s, by reason of the draughts

made from them, and the difficulty the officers

met with in getting men, I believe, I may safely

say, that upon an average they did not exceed 25

Men per Company, and those all new-raised Men. The

three additional Companies of Lord John Murray’s,

I believe, might be pretty near complete; of these

three last I soon after sent one to Inverary, and

the other two, which I took with me, mouldered

away by desertion upon the March northward.”

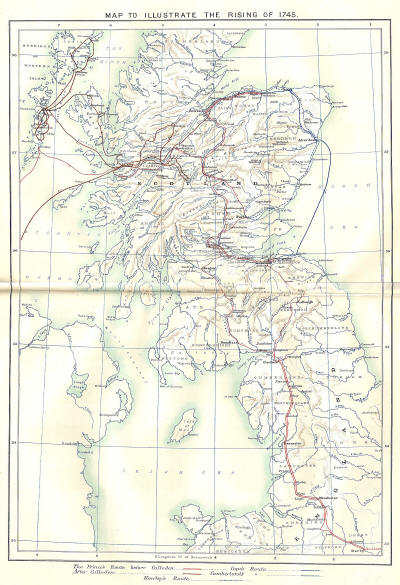

Map to illustrate the

Rising of 1745

The first intimation

of the Prince’s landing reached Cope on August 8.

He at once ordered as many troops as could be

spared from the garrisons to concentrate at

Stirling in readiness for a march into the

Highlands. On the 19th he himself left

Edinburgh to take command of this force, leaving

General Guest at Edinburgh Castle in command of

the whole of the troops in the Lowlands. In the

meantime the Lord President had gone north to

raise the loyal clans for the Government.

Cope left Stirling on

the 20th with five companies of Lee’s,

Murray’s Regiment, and two companies of Lord

Murray’s Highland Regiment. He halted over the 21st

at Crieff to wait for provisions, and there was

joined by eight companies of Lascelles’s. On the

22nd he resumed his march to Amulree,

encountering the utmost difficulties as to

transport. Tay Bridge, now Aberfeldy, was reached

on the 23rd, Trinifuir on the 24th,

Dalnacardoch on the 25th, and

Dalwhinnie on the 26th.

At Dalnacardoch he was

met by Captain Switenham, who had been released by

the insurgents. Switenham informed him that the

Prince’s force was now some 3000 strong, and that

it was his purpose to march over Corryarrack and

descend into the Lowlands.

Cope’s intention had

been to march to Fort Augustus by the Corryarrack

road, and his first idea now was to attempt to

force the pass, but he was soon satisfied that to

attempt to do so in face of a determined enemy

would be to court certain destruction. On the

morning of the 27th he held a council

of war, consisting of all the field-officers and

commanders of corps in his army, to consider what

ought to be done. The council were unanimously of

opinion that an attack upon the pass was out of

the question; that to return to Stirling would

spread the insurrection by encouraging the

disaffected in the north, and would in itself be a

dangerous movement; and that to remain where they

were would not prevent the enemy from reaching the

low county. In these circumstances, it was

determined to continue the march northwards to

Inverness. This was done, and Inverness was

reached on August 29.

The Prince’s way to

the Lowlands was thus left clear. On the 28th

he marched over Corryarrack to Garvemore. It was

at first proposed to pursue Cope, but it was

considered that he had too long a start, and,

accordingly, it was decided to continue the march

to the south by Dalwhinnie and Dalnacardoch. Blair

Castle was reached on August 31, Dunkeld on

September 3, and on the evening of the 4th

the Prince entered Perth, and there proclaimed

King James VIII. At Perth he was joined by many

leading Jacobites, including the titular Duke of

Perth, Lord George Murray, Lord Ogilvie, Oliphant

of Gask, and the Chevalier Johnstone, well known

as one of the historians of the insurrection. Many

recruits came in, including 200 of Robertsons of

Struan, and many others from Atholl and the

surrounding districts. Something was done to

organize the army and to make commissariat

arrangements. A sum of £500 was exacted from the

city of Perth [The money was much needed. It was

said that when he reached Perth the Prince had

only a guinea in his pocket.] Various staff

appointments were made. Lord George Murray and the

Duke of Perth were appointed lieutenant-generals.

The former was not only a devoted Jacobite, but a

man of great capacity and of considerable military

experience. To him was due no small measure of the

success which afterwards attended the Prince’s

arms.

At Perth information

was received that Cope was collecting shipping at

Aberdeen in order to convey his troop once more to

the south. It was according determined to press on

southwards, and, if possible, to anticipate his

return by seizing Edinburgh. On the 11th

the Prince marched out of Perth, and on the same

night reached Dunblane. Next day he marched to

Doune, and on the following day crossed the Forth

at the Fords of Frew. Linlithgow was reached at

six in the morning of Sunday, September 15.

When it became known

that Cope had refused battle to the Jacobite army,

and that Prince Charles was actually advancing on

the Lowlands, the greatest alarm and confusion

prevailed in Edinburgh. The Jacobites were almost

openly triumphant, while the friends of Government

were thrown into the utmost consternation.

Edinburgh was almost defenceless, though it was

still nominally a fortified city. In those days,

it must be remembered, the appearance of the city

was very different from that which it now

presents. Neither the new Town nor the southern

suburbs were then in existence. The city was

bounded and defended on the north side by the Nor’

Loch, a swampy lake which covered the ground now

occupied by Princes Street Gardens; on the west,

south, and east is was surrounded by the old

Flodden wall, which ran from the West port out by

the Vennel to Heriot’s Hospital, thence round by

Potterrow to the east end of the Cowgate, then up

the hill to the Netherbow Port, which crossed the

High Street a little below the Tron Church, and so

down to the Nor’ Loch, separating the old town of

Edinburgh proper from the Canongate, which was

then a separate burgh. This wall, which was just a

strong park dyke, varying from ten to twenty feet

in height, was of little use as a defence in

modern warfare. No guns were mounted upon it,

indeed there were no platforms upon which guns

could be mounted. The wall had no re-entering

angles or flanking bastions; in many places houses

were built up against it. In some cases these

houses were commanded by higher houses opposite to

them, and outside the city; a continuous row of

such houses ran from the Cowgate to the Netherbow

Port. “The condition of the men who might be

called upon to defend them,” says Home, “was

pretty similar to that of the walls.” There was a

body of civic troops called the Trained Bands,

which nominally amounted to sixteen companies of

from 80 to 100 each, but these warriors were not

likely to prove very formidable in the field. Sir

Walter Scott says of them that for many years

their officers “had practiced no other martial

discipline than was implied in a particular mode

of flourishing their wine glasses on festive

occasions, and it was well understood that if

these militia were called on, a number of them

were likely enough to declare for Prince Charles,

and a much larger proportion would be unwilling to

put their persons and properties in danger for

either the one or the other side of the cause.”

Besides these, the only troops available for

defence were the men of the Town Guard, the old

“Town’s Rats,” 126 in number, Gardiner’s dragoons,

who had been left at Stirling, and had retreated

before the advancing Jacobites, and Hamilton’s

dragoons, who were encamped on Leith Links.

Notwithstanding these

disadvantages, it was resolved to make some effort

to defend the city. A meeting was held, at which

it was decided to strengthen the walls as well as

time would permit, and to raise a regiment of

volunteers. The friends of Government were much

encouraged by the arrival of Captain Rogers,

aide-de-camp to Cope, who arrived from the north

with the news that Cope was going to march his

troops from Inverness down to Aberdeen, and bring

them south by sea, in time, if possible, to save

Edinburgh. Their object, therefore, was to defend

the city until his arrival.

On September 6 a

petition was presented to the Town Council by

about 100 citizens praying that they might be

authorized to associate as volunteers for the

defence of the city. The number of volunteers

rapidly increased, and on September 11, six

captains, nominated by the Provost, were appointed

to the regiment. On the following day the

volunteers assembled in the College yards and were

told off into companies, and had arms and

accoutrements served out to them. In the meantime,

fortifications were added to the walls under the

direction of Colin Maclaurin, Professor of

Mathematics in the University. The volunteers were

instructed with all possible speed in the

rudiments of drill, and guns were obtained from

the ships at Leith and mounted on the walls.

On Sunday, September

15, it was rumoured that the van of the insurgents

had reached Kirkliston. It was now proposed that

Hamilton’s dragoons should march up from Leith to

join Gardiner’s at Corstorphine, and that this

force, supported by the city volunteers, should

give battle to the Highlanders in the open. Lord

Provost Stewart offered the services of 90 of the

City Guard. Accordingly, orders were issued by

General Guest to Hamilton’s dragoons to march up

to Edinburgh.

What happened on that

Sunday morning is graphically described by Scott:

“The fire – bell, an ominous and ill – chosen

signal, tolled for assembling the volunteers, and

so alarming a sound, during the time of Divine

service, dispersed those assembled for worship,

and brought out a large crowd of the inhabitants

to the street. The dragoon regiment appeared

equipped for battle. They huzza’d and clashed

their swords at sight of the volunteers, their

companions in peril, of which neither party were

destined that day to see much. But other sounds

expelled these warlike greetings from the ears of

the civic soldiers. The relatives of the

volunteers crowded around them, weeping,

protesting, and conjuring them not to expose lives

so invaluable to their families to the broadswords

of the savage Highlanders. There is nothing of

which men in general are more easily persuaded,

than of the extreme value of their own lives; nor

are they apt to estimate them more lightly when

they see they are highly prized by others. A

sudden change of opinion took place among the

body. In some companies the men said that their

officers would not lead them on; in others, the

officers said that the privates would not follow

them. An attempt to march the corps towards the

West Port, which was their destined route for the

field of battle, failed. The regiment moved,

indeed, but the files grew gradually thinner and

thinner as they marched down the Bow and through

the Grassmarket, and not above forty-five reached

the West Port. A hundred more were collected with

some difficulty, but is seems to have been under a

tacit condition that the march to Corstorphine

should be abandoned, for out of the city not one

of them issued. The volunteers were led back to

their alarm post and dismissed for the evening,

when a few of the most zealous left the town, the

defence of which began no longer to be expected,

and sought other fields in which to exercise their

valour.”

“We remember,” says

Scott, “an instance of a stout Whig and a very

worthy man, a writing-master by occupation, who

had esconced his bosom beneath a professional

cuirass, consisting of two quires of long foolscap

writing-paper; and, doubtful that even this

defence might be unable to protect his valiant

heart from the claymores, amongst which his

impulses might carry him, had written on the

outside, in his best flourish “This is the body of

J--- M---, pray give it Christian burial.’ Even

this hero, prepared as one practiced how to die,

could not find it in his heart to accompany the

devoted battalion further than the door of his own

house, which stood conveniently open about the

head of the lawmarket.”

It is all very well

for Sir Walter to make fun of these worthy

citizens, but probably they acted in the most

judicious possible manner. They were not soldiers

in any sense; they were entirely unaccustomed to

discipline and to the use of arms; had they gone

forth to encounter Lochiel’s fierce swordsmen they

would have been cut to pieces in ten minutes, and

their sacrifice would not have averted the capture

of the city, or even delayed it by a single day.

On the forenoon of the

following day, Monday the 16th, a

message was brought from the Jacobite camp by a

Writer to the Signet names Alves, who said that he

had been taken prisoner by the Jacobites, that he

had seen the Duke of Perth, and had received from

him a message to the inhabitants of Edinburgh to

the effect that it they would admit the prince

peaceably into the city they should be civilly

dealt with; if not, they must lay their account

with military execution. This increased the alarm

of the townsfolk, who now petitioned the Provost

to call a meeting to consider what should be done.

This the Porvost refused to do, as he considered

that with the aid of the two regiments of dragoons

the defence of the city might still be prolonged.

On Tuesday morning the Jacobites advanced to

Corstorphine. The dragoons had been drawn up by

Colonel Gardiner at Coltbridge to dispute their

passage. When the two forces came in sight of each

other some “young people well mounted,” belonging

to the Prince’s force, were ordered to ride out

and reconnoiter the dragoons. These “young people”

rode close up to the dragoons and fired their

pistols at them. Then ensued the “Canter of

Coltbrig.” The dragoons were seized with a general

panic, their officers in vain tried to rally them.

The men turned their horses’ heads and fled in the

utmost confusion. Between three and four o’clock

in the afternoon they galloped through the fields

by the Lang Dykes, where the New Town now stands,

in full view of the citizens. They never stopped

till they reached Leith; there they only made a

short halt. They continued their flight by

Musselburgh, and prepared to bivouac for the night

in a field near Preston Grange, but a cry was

raised that the Highlanders were coming, and these

cowardly troopers again fled, and only stopped

when they reached Dunbar. Nobody had made any

attempt to pursue them.

The city being thus

left defenceless, the townsfolk were driven to

desperation. A meeting of the Town Council has

hastily convened. The Provost sent to request the

attendance of the Lord Justice Clerk, the Lord

Advocate, and the Solicitor-General, in order that

they might assist the Council with their advice;

but these functionaries had discreetly left the

city when the danger became imminent. Many of the

citizens crowded into the Goldsmith’ Hall, where

the Town Council were assembled, clamouring for

surrender. The meeting was adjourned to the New

Church aisle. While the discussion was proceeding

there, a letter addressed to the Lord Provost,

Magistrates, and Town Council was handed in at the

door. On being opened it was found to be

subscribed “CHARLES, P. R.” After some discussion

the letter was read. It contained a summons to

surrender the city; protection was promised to the

liberties of the city and to private property;

“but,” it was continued, “if any opposition be

made to us we cannot answer for the consequences,

being firmly resolved at any rate to enter the

city, and in that case if any of the inhabitants

are found in arms against us, they must not expect

to be treated as prisoners of war.”

When this letter had

been read the cry for surrender became louder than

ever. It was agreed that a deputation should be

sent to wait on the Prince at Gray’s Mill, about

two miles from Edinburgh, where he was, to request

that hostilities should be suspended, in order to

give the citizens an opportunity of considering

the letter.

The deputation was not

long gone when news arrived which entirely altered

the aspect of affairs. This was that Cope’s

transports had arrived from Aberdeen and were

lying off Dunbar, where he proposed to disembark

his troops and to march immediately to the relief

of Edinburgh. Messengers were at once dispatched

to recall the deputation, but they were unable to

overtake it. Many of the more zealous citizens

wished to continue the defence, so as to give Cope

time to come up. However, this idea was abandoned,

as it was remembered that several magistrates and

town councilors were in the power of the

Highlanders, who were regarded as mere ruthless

savages, and who, it was considered, would, in the

event of hostilities being commenced, probably

hang them all. About ten o’clock at night the

deputies returned with a peremptory answer. “His

Royal Highness the Prince Regent,” wrote Secretary

Murray, “thinks his manifesto and the King his

father’s declaration, already published, a

sufficient capitulation for all His Majesty’s

subjects to accept of with joy. His present

demands are to be received into the city as the

son and representative of the King his father, and

obeyed as such when there . . . He expects a

positive answer before two o’clock in the morning,

otherwise he will think himself obliged to take

measures conform.” The unlucky bailies could think

of nothing better than “to send out deputies once

more to beg a suspension of hostilities till nine

o’clock in the morning, that the magistrates might

have an opportunity of conversing with the

citizens, most of whom had gone to bed.” A second

deputation accordingly started for Gray’s Mill

about two in the morning in a hackney-coach. The

Prince refused to see them or to grant any further

delay, and they were briefly ordered to “get them

gone.”

While these

negotiations were going on, the Jacobites, well

knowing the value of time, were quietly making

preparations to take the city by a

coup de main. About midnight Cameron of

Lochiel ordered his men to get under arms, and

very early in the morning a detachment, about 500

strong, started by moonlight from the Borough

Muir, guided by Murray of Broughton. They marched

round by Hope Park to the Netherbow Port,

preserving the strictest silence and keeping well

out of sight of the Castle. When they reached the

Netherbow, Lochiel placed twenty Camerons on each

side of the gate, and hid the rest of his men in

St. Mary’s Wynd and the adjoining streets. He then

sent forward a man in a riding-coat and

hunting-cap, who represented himself as the

servant of an English officer of dragoons, and

asked to be admitted. The guard, however, refused

to open the gat, and ordered the man to withdraw,

threatening to fire upon him.

Day was now breaking,

and Murray proposed that the detachment should

retire to St. Leonard’s Hill, and there await

further orders; but, just as they were about to

leave, a piece of good fortune enabled them to

effect their purpose. It will be remembered that

the second deputation sent out to treat with the

prince went in a hackney-coach. They returned to

Edinburgh in the same coach, and were set down in

the High Street. The driver had his stables in the

Canongate, so, after bringing back the deputation,

he had to pass through the Netherbow Port in order

to get home. He was known to the man on guard, and

accordingly, after some discussion, the gate was

opened to let him pass. Lochiel’s men instantly

rushed in and overpowered, disarmed, and made

prisoners of the guard. Parties were at once

detached to seize the other gates and the town

guard-house. This was quickly and easily done,

without bloodshed; “as quietly as one guard

relieves another,” says Home. This took place

about five in the morning, and the citizens were

presently awakened by the sound of the pibrock, to

find that the Highlanders were masters of

Edinburgh. [Lord Provost Archibald Stewart was

brought to trial in 1747 for neglect of duty and

misbehaviour in the execution of his office in

allowing the city so easily to fall into the hands

of the insurgents. The evidence at his trial is a

valuable source of information as to what took

place.]

About ten o’clock the

main body of the insurgents, having marched round

the south side of Edinburgh, entered the King’s

Park and halted in the Hunter’s Bog. Shortly

afterwards Charles himself appeared. A great crowd

of people was assembled in the park, one of the

spectators being John Home, the historian. He

gives a graphic picture of Charles’s appearance at

the time. “The figure and presence of Charles

Stuart were not ill-suited to his lofty

pretensions. He was in the prime of youth, tall

and handsome, of a fair complexion; he had a

light-coloured periwig, with his own hair combed

over the front; he wore the Highland dress – that

is, a tartan short-coat without the plaid, a blue

bonnet on his head, and on his breast the Star of

the Order of St. Andrew.” After standing for some

time in the park to show himself to the people,

Charles mounted his horse and rode to the door of

Holyrood. He was ushered into the palace of his

fathers by James Hepburn of Keith, one of the most

devoted of Jacobites and the model of a

high-minded and patriotic Scottish gentleman of

the old school.

At mid-day King James

VIII. was solemnly proclaimed at the Cross, and

the Commission of Regency was read, with the

declaration issued at Rome in 1743, and a

manifesto in the name of Charles as Prince Regent,

dated at Paris, May 16, 1745.

The next two days were

spent in Edinburgh. In the meantime Cope had

reached Dunbar. The two regiments of dragoons

which had fled from Edinburgh had come there on

the morning of the 17th, “in a

condition not very respectable.” The

disembarkation of the troops, artillery, and

stores was completed on the 18th, and

Cope found himself at the head of a force of some

2000 men.

Home had made his way

to Dunbar, and by him Cope was furnished with

detailed information as to the strength and

condition of the Highland army. “He was

persuaded,” he said, “that the whole number of

Highlanders whom he saw within and without the

town did not amount to 2000 men; but he was told

that several bodies of men from the north were on

their way, and expected very soon to join them at

Edinburgh . . . Most of them seemed to be

strong, active, and hardy men; many of them were

of very ordinary size, and if clothed like our

countrymen would, in his opinion, appear inferior

to the King’s troops. But the Highland garb

favoured them much, as it showed their naked

limbs, which were strong and muscular: their stern

countenances and bushy, uncombed hair gave them a

fierce, barbarous, and imposing aspect. As to

their arms,” he said, “that they had no cannon or

artillery of any sort but one small iron gun,

which he had seen without a carriage, lying upon a

cart drawn by a little Highland horse. That about

1400 of them were armed with firelocks and

broadswords; that their firelocks were not similar

or uniform, but of all sorts and sized – muskets,

fusees, and fowling-pieces; that some of the rest

had firelocks without swords, and some of them

swords without firelocks; that many of their

swords were not highland broadswords, but French;

that a company or two (about 100 men) had each of

them in his hand a shaft or a pitchfork with the

blade of a scythe fastened to it, somewhat like

the weapon called the Lochaber axe, which the Town

Guard soldiers carry. But all of them,” he added,

“would be soon provided with firelocks, as the

arms belonging to the Trained Bands of Edinburgh

had faller into their hands.”

On the 19th

of September, Cope left Dunbar, and marched

towards Edinburgh. “The people of the county,”

says Home, “long unaccustomed to war and arms

flocked from all quarters to see an army going to

fight a battle in East Lothian.” That night Cope

encamped in a field to the west of Haddington.

The Jacobite leaders

were unanimously resolved to march out and give

battle to Cope in the open. On the morning of

September 20, the Jacobite camp at Duddingston was

struck, and the army commenced its march

eastwards. On the same morning Cope resumed his

march towards Edinburgh by the high road from

Haddington. At Huntington he left the high road,

and followed the road passing through St. Germains

and Seton until he reached the open ground between

Seton and Preston, close to the sea.

From Duddingston the

Prince marched to Musselburgh, and there crossed

the Esk by the ancient bridge. Lord George Murray,

having received intelligence of Cope’s

whereabouts, considered that it was all-important

to attack him if possible from higher ground, and,

accordingly, the line of march was inclined to the

right. The height near Falside was occupied. The

route was then directed downhill towards Tranent,

and the army took up its position to the east of

that village. The enemies were now within sight of

each other, about half a mile apart. Cope had

expected to be attacked from the west, but as soon

as he saw the enemy appear on his left he changed

his front from west to south. On his right were

the village of Preston and the wall of Erskine of

Grange’s park, on his left the village of Seton,

in his rear Cockenzie and the sea, in his front

the enemy and the town of Tranent. The armies were

separated by a piece of impassable boggy ground,

which rendered a direct attack possible.

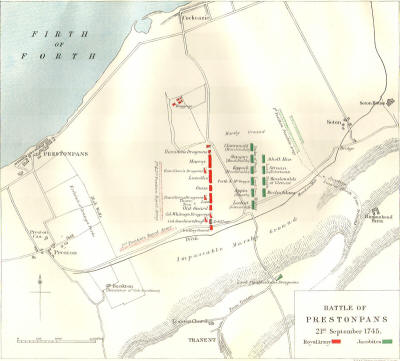

Battle of Prestonpans

The Jacobite leaders

wished to attack Cope at once, and Lord George

Murray sent down an officer to reconnoiter the

marsh. He reported that it was impossible to cross

it and attack the enemy in front without serious

loss. The Jacobites then moved to their left, and

took up a position opposite Preston Tower,

whereupon Cope resumed his first position, facing

Preston, with his right to the sea. Afterwards the

Highlanders returned to their former position, and

Cope did the same.

Both armies lay on

their arms all night. Charles and his officers

held a council of war, and resolved to attack at

daybreak, across the east end of the marsh.

There was in the

Jacobite army a Mr Robert Anderson, son of

Anderson of Whitburgh in East Lothian, who knew

the ground well, as he had often shot over it.

After the council of war had broken up, Anderson

came to Hepburn of Keith, and told him that he

could undertake to point out the place at which

the marsh could be safely crossed by troops,

without their being exposed to the enemy’s fire.

Hepburn sent Anderson to Lord George Murray. Lord

George at once saw the importance of the

information, and wakened the Prince. It was

decided that Anderson’s proposal should be

adopted. Orders were sent to recall Lord Nairn,

who had been detached with 500 men towards

Preston, to head off Cope from the Edinburgh road.

Before daybreak on the 21st the troops

were quietly got under arms, and marched off in

column, three deep, under Anderson’s guidance.

They passed to the east of Ringanhead Farm, across

the marsh, and then marched directly north towards

the sea until the rear of the column was on firm

ground. There they halted, and formed into two

lines to the left.

The first line

consisted of the Clanranald, Glengarry, and

Keppoch Macdonalds, under the Duke of Perth, on

the right, and the Macgregors, the Appin Stewarts,

and Lochiel’s men, under Lord George Murray, on

the left. The second line was commanded by Lord

Nairn, and consisted of the Antholl men, the

Struan Robertsons, the Glencoe Macdonalds, and the

Maclachlans. Charles took his place between the

lines.

Cope was taken

entirely by surprise. As the Highlanders were

crossing the marsh they were seen by some of his

cavalry pickets, who at once galloped in to give

the alarm. When he discovered that he was about to

be attacked from the east, he hastily changed his

front. His line of battle, as originally arranged,

had been as follows: Five companies of Lee’s

regiment on the right, Murray’s regiment on the

left, eight companies of Lascelles’s regiment and

two of Guise’s in the centre, two squadrons of

Gardiner’s dragoons on the right, and two on the

left. Apparently there was considerable confusion

in taking up the new ground. “The disposition was

the same,” says Home, “and each regiment in its

former place in the line, but the outguards of the

foot, not having time to find out the regiments to

which they belonged, placed themselves on the

right of Lee’s five companies, and did not leave

sufficient room for the two squadrons of dragoons

to form; so that the squadron which Colonel

Gardiner commanded was drawn up behind the other

squadron commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Whitney.

The artillery with its guard, which had been on

the left and very near the line, was now on the

right, a little farther from the line, and in the

front of Lieutenant-Colonel Whitney’s squadron.”

[It is very difficult to arrive at any accurate

estimate of the number of troops engaged at

Prestonpans. Cope’s returns were lost, and the

figures given by himself at his trial were given

from memory. The evidence as to the number of the

forces on both sides is very contradictory. It

will be found reviewed in the Notes to the

Chevalier.]

The harvest had just

been got in, and the ground between the armies was

a wide, level stubble field, without a bush or

tree upon it. As the line of the clansmen began to

move forward to the sound of the pipes, the field

was still covered with a thick mist, but presently

the sun rose, the mist lifted, and the opposing

forces became clearly visible to each other. “The

King’s army,” says Home, who was an eye-witness,

“made a most gallant appearance, both horse and

foot, with the sun shining upon their arms.” But

once again the spectacle was seen of a regular

army swept away in a moment by the terrible charge

of the claymores. The battle was a mere rout; it

did not last five minutes. Home thus describes the

scene: “As the left wing of the rebel army had

moved before the right, their line was somewhat

oblique, and the Camerons, who were nearest the

King’s army, came up directly opposite to the

cannon, firing at the guard as they advanced. The

people employed to work the cannon, who were not

gunners or artillerymen, fled instantly. [“When

Sir John Cope marched with his army to the north,

there were no gunners or matrosses to be had in

Scotland but one old man who had belonged to the

Scots train of artillery before the Union. This

gunner and three old soldiers belonging to the

company of invalids in the garrison at the Castle

of Edinburgh, Sir John Cope carried along with him

to Inverness. When the troops came to Dunbar, the

King’s ship that escorted the transports furnished

Sir John Cope with some sailors to work the

cannon; but when the Highlanders came on, firing

as they advanced, the sailors, the gunner, and the

three old invalids ran away, taking the powder

flasks with them, so that Colonel Whiteford, who

fired five of the field pieces, could not fire the

sixth for want of priming. Sir John Cope had only

four field-pieces when he came to Inverness, but

he ordered two field-pieces to be taken from the

Castle there and added to his train.” – Home, p.

113,

note. At Prestonpans there were only from

ten to fifteen rounds of ammunition per gun.

Evidence of Robert Jack, Cope’s Trial.] Colonel

Whiteford fired five of the six field-pieces with

his own hand, which killed one private man and

wounded an officer in Lochiel’s regiment. The line

seemed to shake, but the men kept going on at a

great pace; Colonel Whitney was ordered to advance

with his squadron and attack the rebels before

they came up to the cannon: the dragoons moved

on, and were very near the cannon when they

received some fire which killed several men and

wounded Lieutenant-Colonel Whitney. The squadron

immediately wheeled about, rode over the artillery

guard, and fled. The men of the artillery guard,

who had given one fire, and that a very

indifferent one, dispersed, the Highlanders going

on without stopping to make prisoners. Colonel

Gardiner was ordered to advance with his squadron

and attack them, disordered as they seemed to be

with running over the cannon and the artillery

guard. The Colonel advanced at the head of his

men, encouraging them to charge; the dragoons

followed him a little way; but as soon as the fire

of the Highlanders reached them they reeled, fell

into confusion, and went off as the other squadron

had done. When the dragoons on the right of the

King’s army gave way, the Highlanders, most of

whom had their pieces still loaded, advanced

against the foot, firing as they went on. The

soldiers, confounded and terrified to see the

cannon taken and the dragoons put to flight, gave

their fire, it is said, without orders; the

companies of the outgruard being nearest the

enemy, were the first that fired, and the fire

went down the line as far as Murray’s regiment.

The Highlanders threw down their muskets, drew

their swords and ran on; the line of foot broke as

the fire had been given from right to left;

Hamilton’s dragoons, seeing what had happened on

the right, and receiving some fire at a good

distance from the Highlanders advancing to attack

them, they immediately wheeled about and fled,

leaving the flank of the foot unguarded. The

regiment which was next them (Murray’s) gave their

fire and followed the dragoons. In a very few

minutes after the first cannon was fired, the

whole army, both horse and foot, were put to

flight; none of the soldiers attempted to load

their pieces again, and not one bayonet was

stained with blood. In this manner the battle of

Preston was fought and won by the rebels; the

victory was complete, for all the infantry of the

King’s army were either killed or taken prisoners,

except about 170, who escaped by extraordinary

swiftness, or early flight.”

Johnstone’s

Memoirs (Ed. 1822), p. 29

et seq. The following are the figures as

given by Mr Blaikie (Itinerary, pp. 90 and 91), probably as

accurate an estimate as can be reached:

SIR JOHN COPE’S ARMY.

EXCLUSIVE OF OFFICERS,

SERGEANTS, DRUMS, ETC.

Rank and File.

Three Squadrons Gardiner’s Dragoons (13th

H.) . . . .

Three “ Hamilton’s “

(14th H.) . . . . 1567

Five Companies Lee’s Regiment (44th)

. . . . . . . 291

Murray’s Regiment (46th) . .

. . . . . . . . . . 580

Eight Companies Lascelles’s Regiment (47th)

. . . .

Two “ Guise’s

“ (6th) . . . . .

1570

Five Weak Companies of Highlanders of Lord John

Murray’s Regiment (42nd), and Lord

Loudon’s Regiment 183

Drummond’s (Edinburgh) Volunteers . . . .

. . . . 16

2207

Add same proportion of officers, sergeants, drums,

etc., as recorded at Culloden (16 per

cent.) . . . 353

TOTAL 2560

Six guns and some cohorns (mortars).

They had no gunners; Lt. Colonel Whiteford

(Marines) served the guns with his own hands, and

Mr Griffith (Commissary) the cohorns.

THE PRINCE’S ARMY.

Clanranald . .

. . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . 200

Lochiel . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . 700

Keppoch . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . 300

Stewart of Appin . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . .

260

Glengarry . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . 400

Glencoe . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . 120

Robertson of Struan . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . 200

Duke of Perth . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . 150

Maclochlans . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . 150

Lord Nairn . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . 150

Grants of Glenmoriston . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . 100

Cavalry . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

50

2880

Less dismissed by Liochiel, August 30 . .

. . . . . . .

150

2730

Allowance for desertion by Keppoch’s men (Aug 27),

and a further allowance for leakage owing to

desertion, illness, guards, etc., less a few men

recruited in Edinburgh 150

Colonel Gardiner, who,

though severely wounded, had in vain attempted to

rally his men, was killed by the stroke of a

Lochaber axe. “The panic terror of the English

surpasses all imagination,” says the Chevalier

Johnstone, “they threw down their arms that they

might run with more speed, thus depriving

themselves by their fears of the only means of

arresting the vengeance of the Highlanders. Of so

many men in a condition from their numbers to

preserve order from the retreat, no one thought of

defending himself. Terror had taken entire

possession of their minds. I saw a young

Highlander about fourteen years of age, scarcely

formed, who was presented to the Prince as a

prodigy, having killed, it was said, fourteen of

the enemy. The Prince asked him if this was true.

‘I do not know if I killed them, but I brought

fourteen soldiers to the ground with my sword.’

Another Highlander brought ten soldiers to the

prince, whom he had made prisoners, driving them

before him like a flock of sheep. This Highlander,

from a rashness without example, having pursued a

party to some distance from the field of battle

along the road between the two enclosures, struck

down the hindermost with a blow of his sword,

calling at the time ‘Down with your arms.’ The

soldiers, terror-struck, threw down their arms

without looking behind them, and the Highlander,

with a pistol in one hand and a sword in the

other, made them do exactly as he pleased. The

rage and despair of these men on seeing themselves

made prisoners by a single individual may easily

be imagined. These were, however, the same English

soldiers who had distinguished themselves at

Dettingen and Fontenoy, and who might justly be

ranked among the bravest troops of Europe.”

The field of battle

presented a hideous spectacle, as the killed and

wounded had almost all fallen by the edge of the

sword. According to Home, the royal troops lost 5

officers and 200 men killed, [This is probably

under-estimated. Johnstone says 1300, which is out

of the question. The real number was probably some

400 or 500.] and 80 officers taken prisoners. The

Jacobite loss was 4 officers and 30 men killed, 6

officers and 70 men wounded. Cope’s cannon, tents,

baggage, and military chest, containing some

£2500, were captured. The unlucky general himself,

with his principal officers and such of the

cavalry as had kept together, fled by Lauder and

Coldstream, the next day reached Berwick, where he

was received by old Lord Mark Kerr with the famous

remark: “Good God! I have seen some battles,

heard of many, but never of the first news of

defeat being brought by the general officers

before.”

The night Prince

Charles slept at Pinkie House; next day he

re-entered Edinburgh in triumph.

After the victory the

Highlanders treated their conquered enemies with

great forbearance. To the wounded of the royal

army they showed a humanity which might well have

been imitated by the regulars on a subsequent

occasion. They were, however, very active in

despoiling the dead. They appropriated wigs,

watches, clothes, saddlery, and whatever else they

could lay hands on. Their ignorance of civilized

life sometimes led them into absurd mistakes,

about which some good stories are told. One of the

best known of these is that of the Highlander who

helped himself to an English officer’s watch. Not

knowing the nature of a watch, he omitted to wind

up his new possession, which, accordingly, stopped

during the night. Next day he sold it for a

trifle, saying that he was glad to be rid of it,

“because she had dee’d in ta nicht-time.”

On Monday, September

23, the day after his return to Edinburgh, Prince

Charles issued several proclamations. He promised

protection to the citizens; he forbade all public

rejoicings for his victory, which had been

purchased with the shedding of so much British

blood and attended with calamity to so many

innocent people. He further directed that public

worship should be conducted as usual in the city

churches. A deputation of the city ministers

waited on him to ask whether they would be allowed

to offer the usual prayers for King George. The

Prince replied that he could not expressly grant

them their request without giving the lie to his

own pretensions; but, at the same time, he

promised that no minister should be called to

account for any indiscreet language he might use

in the pulpit. Mr M’Vicar, the minister of the

West Kirk, managed to compromise matters in his

prayers by offering the following petition:

“Bless the King! Thou knows what King I mean. May

the crown sit long upon his head. And for the man

that is come among us to seek an earthly crown, we

beseech Thee in mercy to take him to Thyself and

give him a crown of glory.”

The victory of the

Prestonpans entirely altered the aspect of

Charles’s affairs. At first his enterprise had

been looked upon, even by his warmest friends, as

a piece of Quixotic folly which had no reasonable

prospect of success. Now he had beaten the King’s

troops in a pitched battle, and was master of all

Scotland except the Castles of Edinburgh and

Stirling and the Highland forts. Now he had to

make up his mind what he was going to do next.

There were two courses open to him, either to

invade England at once, or to stay in Edinburgh

for a while to recruit his army and to collect

stores, arms, and ammunition. Every day was

strengthening the hands of the Government; troops

were being recalled from Flanders; 6000

auxiliaries were being sent over by the States of

Holland and, as soon appeared, preparations were

being made to send a strong force to the north

under Marshal Wade. On the other hand, it was

considered with justice that the news of

Prestonpans would soon bring abundance of recruits

from the Highlands. It was decided to remain for a

few weeks in Edinburgh.

The greatest efforts

were made to collect munitions of war.

Requisitions were made of stores and public money.

A sum of £5000 was levied from the city of

Glasgow, and parties were sent out in all

directions to beat up recruits. The weeks which

followed Prestonpans were the halcyon time of

Jacobitism. Prince Charles’s followers were

flushed with victory and confident of success. The

Prince himself kept a royal court at Holyrood, as

if he were already at St. James’s. He spent his

days in the camp and the council chamber; [“The

Prince formed a Council which met regularly every

morning in his drawing-room. The gentlemen whom he

called to it were the Duke of Perth, Lord Lewis

Gordon, Lord George Murray, Lord Elcho, Lord

Ogilvie, Lord Pitsligo, Lord Nairne, Lochiel,

Keppoch, Clanranald, Glencoe, Lochgarry, Ardshiel,

Sir Thomas Sheridan, Colonel O’Sullivan,

Glenbucket, and Secretary Murray. The Prince, in

this Council, used always first to declare what he

himself was for, and then he asked everybody’s

opinion in their turn. There was one-third of the

Council whose principles were that kings and

princes can never either act or think wrong, so,

in consequence, they always confirmed whatever the

Prince said. The other two-thirds, who thought

that kings and princes thought sometimes like

other men, and were not altogether infallible, and

that this Prince was no more so than others, and,

therefore, begged leave to differ from him when

they could give sufficient reasons for their

difference of opinion. This very often was no hard

matter to do, for as the Prince and his old

governor, Sir Thomas Sheridan, were altogether

ignorant of the ways and customs of Great Britain,

and both much for the doctrine of absolute

monarchy, they would very often, had they not been

prevented, have fallen into blunders which might

have hurt the cause. The Prince could not bear to

hear anybody differ in sentiment from him, and

took a dislike to everybody that did; for he had a

notion of commanding this army as any general does

a body of mercenaries, and so let them know only

what he pleased, and expected them to obey without

enquiring further about the matter. This might

have done better had his favourites been people of

the country, but, as they were Irish, and had

nothing to risk, the people of fashion that had

their all at stake, and consequently ought to be

supposed capable to give the best advice of which

they were capable, thought they had a title to

know and be consulted in what was for the good of

the cause in which they had so much concern; and

if it had not been for their insisting strongly

upon it, the Prince, when he found that his

sentiments were not always approved of, would have

abolished this Council long ere he did.” – Lord

Elcho’s account, citied by Scott,

Tales of a Grandfather, chap. lxix.] in the

evenings, says Home, “he received the ladies who

came to his drawing-room; he then supped in

public, and generally there was music at supper,

and a ball afterwards.” His own personal

popularity was unbounded. If he had some of the

Stuart vices he certainly had a very ample share

of the Stuart charm. With his youth, his good

looks, his kindness and his courage, he won the

goodwill of everyone who saw him. Of course the

women were wild about him; not a few of them

mounted the White Cockade and gave their jewels

and treasured heirlooms to raise a little money

for his service. There was a certain Miss Isabella

Lumnisden, who plainly told her lover, a young

artist named Robert Strange, that he need think no

more of her unless he joined Prince Charlie.

Strange, who afterwards became Sir Robert Strange,

the most famous line engraver of his time, joined

the Prince’s Guards and suffered exile for the

cause. He fought at Culloden, and only escaped his

pursuers by hiding under his sweetheart’s ample

hood. We are indebted to him for a picturesque and

detailed account of the battle and the night march

which proceeded it. [See p. 153. It is pleasant to

note that Strange had his reward; he married Miss

Lumisden in 1747.

In the meantime, the

good folk of Edinburgh were not without a taste of

the miseries of war. There was still a small

garrison of royal troops in the castle. Shortly

after the battle the castle was blockaded by the

Highlanders. General Guest, the commandment,

demanded that the blockade should be raised

forthwith, and informed the Lord Provost that

unless communication between the castle and the

city were renewed he would open fire upon the

city. A night’s respite was granted, and the

General’s communication was laid before Prince

Charles. The Prince expostulated upon the

unreasonableness of punishing the citizens for

what after all was no fault of theirs. The

commandant consented to postpone the bombardment

till he should receive orders from London.

However, on October 1 the Highlanders fired upon a

party who were going up the Castle Hill with

provisions. Next day the Castle fired upon the

houses that covered the Highland guard. The Prince

replied by strengthening the blockade, whereupon

the cannonade of the city was actually commenced.

Throughout the afternoon of October 4 and on the

following day fire was maintained from the

Half-Moon battery upon the city. Several houses

were destroyed, and the citizens were frightened

out of their wits. Yielding to their earnest

entreaties, the prince consented to raise the

blockade. A very vivid picture of the stated of

affairs in Edinburgh during the Prince’s

occupation, and of the conditions under which

business was carried on, is given in the diary of

Mr. John Campbell, then principal cashier of the

Royal Bank of Scotland, which was recently printed

by the Scottish History Society (Miscellany,

vol. i., pp. 537-559

et seq.).

By the end of October

the Prince’s army had increased to nearly 6000

men. Many recruits had come from the north under

Lord Ogilvie, Gordon of Glenbucket, Lord Pitsligo,

Lord Lewis Gordon, Cluny MacPherson, the Marquis

of Tullibardine, and other. He had also been

joined by the Earls of Kilmarnock and Nithsdale

and Lord Kenmure. Two troops of Life Guards, under

Lord Elcho and Lord Balmerino, had been organized,

and a train of artillery had been formed. By this

time Wade was at Newcastle at the head of a

powerful force. [As to the strength and

composition of Wade’s force, see Mr Blaikie’s

Itinerary, p. 95. It was estimated at the

time at 14,000 foot and 4000 horse, probably an

exaggeration.] Charles was eager to fight him

without delay, and urged an immediate march into

England. His advisers counseled further delay;

ultimately a middle course was adopted; it was

decided to cross the Border at Carlisle, so as to

avoid immediate collision with Wade’s army. This

would afford an opportunity to the English

supporters of the cause to rise, and at the same

time would impose upon Wade the necessity of a

fatiguing march before he could bring the invaders

to an action. On the 31st of October

the Prince marched out of Edinburgh, and his army

rendezvoused at Dalkeith. It was decided that the

march into England should be made in two columns.

One, under the Duke of Perth, was to march to

Carlisle by the western road, by Peebles and

Moffat; the other, commanded by the Prince

himself, took the road by Lauder and Kelso. Lord

George Murray accompanied the Prince.

The Prince’s column

reached Lauder on November 3, Kelso on the 4th,

and Jedburgh on the 6th. On the 8th

he crossed the Esk into England, and on the

following day was joined by the western column;

the whole army encamped for the night in the

villages to the west of Carlisle. On the 10th

Carlisle was summoned to surrender. Pattison, the

deputy mayor, refused, and preparations were being

made for a siege when news arrived that Wade was

about to march from Newcastle to relieve Carlisle.

The troops were accordingly withdrawn from the

trenches, and were marched to Brampton, where they

encamped on the 12th. It turned out,

however, that Wade was not moving, accordingly the

siege of Carlisle was resumed, and on the 15th

the town and Castle both surrendered on terms. On

the 17th the Prince entered Carlisle,

with a hundred pipers playing before him.

A few days after the

surrender of Carlisle, a council of war was held

to consider the next step. The effective force of

the army had been greatly reduced to desertion on

the march from Edinburgh, and did not now exceed

4500. There were four possible courses of action:

to march to the east and attack Wade; to return to

Scotland; to continue the march towards London; or

to sit still at Carlisle and see if the English

Jacobites would rise, which as yet they showed no

sign of doing. The general opinion of the chiefs

was that the Prince should return to Edinburgh and

carry on a defensive war in Scotland till such

time as he was in a condition to attempt invasion.

The Prince, however, insisted on continuing the

march to the south, and at length the chiefs

assented.

The cavalry left

Carlisle on November 20, and marched that day to