|

A

DETAILED account of the

causes which led to the Civil War in the time of

Charles I. would be beyond the scope of this work. The

ill-advised scheme of establishing Episcopacy in

Scotland, which, so far as Scotland was concerned, was

the main cause of the troubles, had, even before the

Union of the Crowns, been a favourite project of James

VI., who was of opinion that "a Scottish Presbytery

agreeth as well with a monarchy as God with the

devil." So long as the seat of monarchy remained at

Edinburgh it was hopeless for any Scots sovereign to

force a great religious change upon an unwilling

people. The increase of power and independence which

came with the accession to the English throne put the

King in a very different position. In i6o6 the

Scottish bishops were restored, with seats in

Parliament. In i6i8 the famous Five Articles of Perth

were passed in a General Assembly held there. By these

certain forms of Episcopal worship were introduced.

They were harmless enough from the modern point of

view, but at the time they aroused deep and bitter

feeling throughout the country. [The Five Articles

sanctioned - (1) Kneeling at Communion; (2)

administration of Communion to the sick in their own

houses; (3) private baptism; (4) confirmation of

children; and (5) observance of the festivals of

Christmas, Good Friday, Easter, Ascension, and

Pentecost.] An ecclesiastical Court of High Commission

was established, and in 1621 the Five Articles were

ratified by the Estates, a majority being obtained

with the utmost difficulty.

James

VI. died in 1625. Charles I. inherited his purposes,

but set about their realisation in a stern and

resolute temper very different from his father’s. What

to James had been matter of policy was to Charles

matter of conscience. His course of action soon

brought matters to a serious crisis. One of his first

acts was the resumption, by an act of prerogative, of

the Church revenues which had been granted away by the

Crown since the Reformation. [See, for an account of

the exceedingly important transactions with regard to

ecclesiastical property at this time, Hill Burton’s

History of Scotland, vol. vi., pp. 75-85.] These

were chiefly held by the higher nobility, and the

result of the King’s act was to create bitter

hostility to the Crown on the part of many of the

great nobles, and to array them on the side of the

popular party in the Church. The King’s visit to

Scotland in 1633 brought further matter of offence.

Serious allegations were made that he had tampered

with the constitutional powers of the Estates. The

appointment of Laud as Archbishop of Canterbury gave

the King as his chief adviser an ecclesiastical

statesman who was little disposed to compromise, and

who, as it proved, knew nothing of the temper of the

Scottish people. In 1636 the Episcopalian Book of

Canons was promulgated by royal authority. In the

following year the Service Book was issued. The

attempt to enforce its use caused the long-gathering

storm to break.

The new

liturgy was used for the first time in St. Giles’s

Cathedral, Edinburgh, on Sunday, July 23, 1637.

The riot which took place in the church, of which

Jenny Geddes is the traditional heroine, is one of the

best known incidents in Scottish history. Similar

riots took place all over the country, and these were

only the beginning of an agitation which soon became a

great national movement. The popular party was known

as the Supplicants, and assumed throughout an attitude

of scrupulous humility. The Government was obdurate;

the King and his advisers seem to have entirely

misjudged the strength and character of the

opposition. In the winter of 1637 was formed the

committee known as the Tables, which was recognised by

the Privy Council as representing the whole body of

the Supplicants, and which soon became a power in the

State co-ordinate with the Council itself. The Tables

were four in number, representing respectively the

nobles, the lesser barons, the burghs, and the

ministers. Each Table consisted of four persons. A

member of the Table of nobility was the young Earl of

Montrose.

In

February 1638 the National Covenant was signed. This

famous document was in the form of a renewal of the

Covenant which had been signed in the early days of

Protestantism, with additions relative to the new

dangers which threatened Church and State. It was

scrupulously loyal in its language, but very explicit

with regard to the great question of the hour. "We

promise and swear," said the signatories, "by the

great name of the Lord our God, to continue in the

profession and obedience of the said religion; and

that we shall defend the same and resist all those

contrary errors and corruptions, according to our

vocation, and to the utmost of that power which God

hath put into our hands all the days of our life."

The

project of renewing the Covenant is commonly

attributed to Archibald Johnston of Warriston. It was

an admirably devised and entirely successful plan for

uniting and organising the anti-prelatical party

throughout the kingdom. In the Greyfriars Churchyard

at Edinburgh, on February 28, 1638, the Covenant was

subscribed by a vast crowd amid a scene of wild

enthusiasm. Copies were sent all over the country.

Every effort was used to obtain signatures; both

persuasion and coercion were freely employed and

thousands of names were adhibited. Henceforth the

popular party was known by the historic name of

Covenanters, and came to be identified not only with

the cause of Presbyterianism as against Episcopacy,

but with the cause of national independence as against

English aggression.

In the

summer of 1638

the Marquis of Hamilton came down

from London as Commissioner from the King to deal with

the Covenanters. He had the widest powers. His

confidential instructions were to gain time by every

possible means, until the King should be in a position

to suppress the Covenanters by force.

The demands of

the Covenanters were explicit enough. They included

the abolition of the Court of High Commission, the

withdrawal of the obnoxious Book of Canons and

Liturgy, a free Parliament, and a free General

Assembly. It was well understood that Parliament and

the Assembly would probably make a clean sweep of

Episcopacy, and Hamilton tried in vain to obtain from

the Covenanting leaders a guarantee that in the event

of their meeting they should not go beyond certain

limits. At length, after much temporising, and various

journeyings between London and Edinburgh on the part

of the High Commissioner, an entire surrender was

announced. The Service Book, the Book of Canons, and

the High Commission were revoked. A meeting of

Assembly was proclaimed for November 21, and

Parliament was to be summoned in the following May.

By this time,

however, it was clear that sooner or later matters

must come to the arbitrament of the sword. The

Covenanters were quietly making preparations for war.

Early in the year the nucleus of a war-chest was

raised by subscription, the list of subscribers being

headed by Montrose. Arrangements were made for the

collection throughout the country of a "voluntary"

contribution, which seems to have been as rigidly

exacted as any tax. Large quantities of arms were

purchased in Holland. Scots officers trained in the

Thirty Years’ War were unobtrusively brought over from

the Continent. The great stronghold of the Royalist

party was in Aberdeenshire, and by far the most

powerful of the King’s adherents was the "Cock of the

North," George, Marquis of Huntly, chief of the great

house of Gordon. An attempt was made to gain him over.

Colonel Robert Monro, the original of Scott’s Dugald

Dalgetty, was sent to Strathbogie with tempting

offers, including a promise to pay off the Marquis’s

debts, which amounted to about £100,000 sterling.

Huntly’s answer uncompromisingly expressed the spirit

of Cavalier loyalty. "His family," he said, had risen

and stood by the Kings of Scotland, arid for his part,

if the event proved the ruin of this King, he was

resolved to lay his life, honours and estate under the

rubbish of the King’s ruins."

On November 21,

1638, the General Assembly met in Glasgow Cathedral.

The Marquis of Hamilton was present as Commissioner;

Alexander Henderson was chosen Moderator, and Johnston

of Warriston Clerk of Assembly. The elections had been

worked by the Tables so as to produce a thoroughly

Covenanting Assembly. Everybody knew what its main

business was to be—the trial of the bishops. The first

few days were occupied in formal and preliminary

business. On the seventh day of meeting it was

formally decided that the bishops were amenable to the

jurisdiction of the Assembly. Thereupon the

Commissioner, in the King’s name, declared the

Assembly dissolved, and on the following day its

further meeting was discharged by proclamation under

pain of treason.

The Assembly proceeded with its

business. The bishops were tried and deposed on

various grounds ;

six of them, together with

the two archbishops, were excommunicated. The whole

fabric of Episcopacy, Service Book, Book of Canons,

Articles of Perth and all, was demolished, and the

Episcopal office was declared to be for ever

abrogated. The Assembly rose on December 20.

"We

have now," said the Moderator,

"cast down the walls of Jericho;

let him that rebuildeth them

beware of the curse of Hiel the Bethelite."

The Covenanters

had now openly defied the royal authority, and war was

inevitable.

The great

struggle was to take place in England, but it was in

the north of Scotland that the first blow was struck.

Aberdeenshire was, as we have seen, the main

stronghold of the Royalist party, and there efforts to

gain adherents to the Covenant had met with little

success. In prospect of a more serious conflict in the

south, the Covenanting leaders determined first to get

rid of the enemy in their rear, and for this purpose

an army of some three or four thousand men was

organised under the Earl of Montrose.

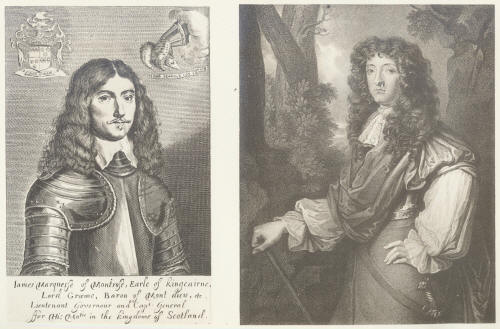

James Graham,

Earl and afterwards Marquis of Montrose, head of the

house of Graham, was at this time a young man of

seven-and-twenty. He was a man of unbounded energy and

ambition; his mental powers had been trained by

education at the University of St. Andrews and by

foreign travel; and, as was soon to appear, he

possessed in the highest degree the qualities of a

leader of irregular troops—personal courage, dash,

resourcefulness in emergency, and unfailing constancy

in misfortune. Cardinal de Retz said of him that more

nearly than any man of his age he resembled one of the

heroes of antiquity. He seems to have possessed a

marvellous personal magnetism. Patrick Gordon of

Ruthven says of him that "he was so affable, so

courteous, so benign, as seemed verily to scorne

ostentation and the keeping of state, and therefore he

quickly made a conquest of the hearts of all his

followers, so as when he list he could have led them

in a chain to have followed him with cheerfulness in

all his enterprises; and I am certainly persuaded that

this his gracious, humane, and courteous freedom of

behaviour . . . was it that won him so much renowne

and enabled him chiefly, in the love of his followers,

to go through so great enterprises." His early

association with the Covenanters is attributed to his

having met with an unexpectedly cold reception from

the King on his return from his travels. Be this as it

may, we find him in the spring of 1639 at the head of

the Covenanting army destined for the North.

Having been

joined by General Alexander Leslie, the veteran of the

Thirty Years’ War, who acted as his military adviser,

Montrose marched on Aberdeen. His army was excellently

equipped and organised, "weill armed," says Spalding,

"both on horse and foot, ilk horseman having

five shot at the least, with ane carabine in his hand,

two pistols by his sides, and the other two at his

saddell toir; the pikemen in their ranks, with pike

and sword; the musketeers in their ranks, with musket,

musketstaff, bandelier, sword, powder, ball, and

match. Ilk company, both on horse and foot, had their

captains, lieutenants, ensigns, sergeants, and other

officers and commanders, all for the most part in

buffle coats and goodly order."

On the approach

of the Covenanting army Aberdeen was abandoned by the

Marquis of Huntly, and Montrose entered the town

peaceably on March 30. At Aberdeen his army was

augmented by the accession of 500 Campbells, whom

Argyll had sent from the west, and of many Frasers,

Keiths, and others, who joined him rather out of

hatred to the Gordons than from any love of the

Covenant. Leaving a strong garrison in Aberdeen, he

marched northward against Huntly. Huntly, however,

opened negotiations, and was ultimately induced to

come to Aberdeen, where he was made a prisoner and

sent to Edinburgh. There the strongest pressure was

brought to bear on him to sign the Covenant, but he

remained steadfast in his loyalty. "For my own part,"

said he "I am in your power, and resolved not to leave

that foul title of traitor as an inheritance upon my

posterity. You may take my head from my shoulders, but

not my heart from my sovereign."

The main body of

the Covenanting army marched southward in April. In

the following month the first blood was drawn in the

civil war. A body of some 2000 Covenanters assembled

at Turriff on May 13. There they were attacked by a

force of the Gordons, with four field-guns. The

Covenanters were defeated and driven out of the town.

This was the affair known as the "Trot of Turray." The

victors marched on Aberdeen, and entered it on May 15.

A few days later they disbanded their army. The chiefs

remained in Aberdeen until they were driven out by the

advent of the Earl Marischal, who entered the town on

May 23. Two days later he was joined by Montrose with

4000 men.

After some

operations against the castles of some of the

Aberdeenshire Royalists, Montrose again retired to the

south, and in June Aberdeen was once more occupied by

the Royalists under Lord Aboyne. On June 14 they

advanced upon Stonehaven. They camped for the night at

Muchalls, and on the following day were attacked and

defeated by the Earl Marischal and Montrose, who had

marched north to meet them. They fell back on

Aberdeen. Montrose followed them up, forced the Bridge

of Dee, and again entered Aberdeen in triumph. Next

day hostilities were brought to an end by the news of

the Pacification of Berwick.

While these

events were taking place in the north, preparations

for war on a much larger scale were going on in the

Lowlands. On February 27 the King, determined to

reduce his rebellious subjects to obedience, issued

the Commission of Array, calling upon the feudal force

of England to assemble at York. In Scotland the royal

fortresses were seized by the Tables, and an army of

over 22,000

men, well organised and equipped, was assembled at

Edinburgh. On May 21 it began its march towards the

Border under the command of that "little old crooked

soldier," Alexander Leslie. The army was accompanied

by a contingent of Argyll’s Highlanders. These

"uncanny trewsmen "—the phrase is Robert Baillie’s

[The letters of the Rev. Robert Baillie, afterwards

Principal of the University of Glasgow, form one of

the most valuable sources of information as to the

military and political events of the time.]—seem to

have been a source of considerable anxiety to their

friends. It is curious to note that Highland troops

should have made their first appearance on the Borders

as the allies of the Covenant.

The two armies

never came to blows. The Scots encamped on Duns Law.

The King was on the other side of the Tweed.

Negotiations were opened, which resulted in the

Pacification of Berwick. It was agreed that the royal

fortresses were to be restored, and the questions at

issue were to be left to the arrangement of a free

General Assembly and a free meeting of the Estates.

The Pacification

of Berwick merely postponed hostilities. From the

first each party accused the other of bad faith. War

broke out again in the following summer. In July the

Scots army was again assembled for the invasion of

England, and on August

28, 1640, the battle of

Newburn was fought.

During

the next four years there was no important fighting in

the north. In Scotland the Covenant was supreme. What

restlessness there was among the Aberdeenshire

Royalists was suppressed by a force under General

Monro. In the summer of 1640 Argyll, acting under a

"Commission of Fire and Sword" from the Estates,

ravaged the lands of his feudal enemies in the central

Highlands and in Angus. It was during this ferocious

raid that there took place that destruction of Airlie

Castle, which forms the subject of the ballad of the

"Bonnie House of Airlie."

The

Long Parliament met in November 1640. In the autumn of

1641 the King visited Scotland, and was present at a

meeting of the Estates, at which, in outward form, all

was harmony; the troubles were brought to an end, and

honours and offices were lavished on the Covenanting

leaders. On Charles’s return to London he found his

difficulties with the English Parliament thickening

fast. On August 25, 1642, the Royal Standard was

raised at Nottingham and the great English Civil War

began.

At

first things went badly for the Parliamentary cause,

and every endeavour was made by its leaders to secure

the help of Scotland against the King. In 1643 the

Solemn League and Covenant was signed. It was followed

by the march of a Scots army into England, again

commanded by Sir Alexander Leslie, now Earl of Leven,

who had as his major-general his more famous nephew,

David Leslie. On July 3, 1644, the combined armies

decisively defeated the King at Marston Moor.

Long

before this Montrose had severed his connection with

the Covenant, and had cast in his lot with the King.

Immediately after the raising of the Royal Standard at

Nottingham, Charles had written to him asking for his

advice and assistance. Now that the English

Parliamentary party had secured the co-operation of

the forces of the Covenant, the King was sorely

overmatched. If the Scottish army could be compelled

to recross the Border, the conditions would be again

equalised. Montrose knew the Highlanders thoroughly.

They were unaccustomed to discipline; they owned no

allegiance except to their own chiefs; it was hopeless

for any ordinary general to attempt to handle them as

a regular army: but Montrose well knew how formidable

a force they might be under a leader who could secure

their confidence and who knew how to manage them. He

believed that he was himself such a leader, and, as

the result proved, his belief was entirely justified.

He conceived the idea of marching into Scotland with a

force which was strong enough to make its way to the

Highlands, and which might there form the nucleus of

an army to be composed of the loyal clans and certain

Irish supports which had been promised by the Earl of

Antrim.

Montrose received from the King a commission, dated

February 1, 1644, by which he was appointed Lieutenant

- General of the royal forces in Scotland. He found

himself, however, unable to obtain a body of troops

sufficient to force his way to the Highlands as he had

designed. He accordingly resolved to find his way

through the enemy’s country in disguise, a

characteristic beginning of the brilliant and daring

enterprise which has immortalised his name, and

thoroughly in accordance with the character of the

leader who was ever ready to stake all upon a single

cast.

The

companions of his perilous journey were Major,

afterwards Sir William, Rollo and Colonel Sibbald.

Montrose passed as their servant. On August 22 the

party reached the house of Tullibelton, near Dunkeld,

which belonged to Montrose’s kinsman, Graham of

Inchbrakie.

There

he lay for some time in hiding, and sent out

messengers to collect intelligence as to the state of

the royal cause in the country. They returned with the

worst news. Under the stern rule of Argyll and the

Committee of Estates, the King’s adherents had been

thoroughly cowed. The enterprise seemed hopeless.

At last

news came that the promised Irish succour had landed.

Instead of the 10,000 men who were expected, a force

of some 1500, commanded by Alastair Macdonald (called

Colkitto, "the left-handed,") had reached the Hebrides

in July, and had subsequently landed in Knoydart. They

had found little support among the western clans.

Montrose succeeded in communicating with Colkitto, and

directed him to march with all despatch into Atholl.

They met at Blair, and there the standard was joined

by some 800 of the Atholl men, chiefly Stewarts and

Robertsons.

Montrose was now at the head of some 3000 men.

Promptitude of action was everything. Argyll, who had

assembled a force to attack Colkitto, was approaching

from the west. Montrose at once determined to strike a

blow at Perth before Argyll could come up. He

accordingly marched southward and crossed the Tay.

Perth

was defended by a force of 6000 foot and 700 horse,

with four guns, the whole commanded by Lord Elcho.

Montrose was thus vastly outnumbered; he had neither

cavalry nor artillery; and not a few of his men had no

better arms than the stones which they picked up on

the battle-field.

The

armies met on the 1st of September at Tippermuir,

between four and five miles to the west of Perth. The

right wing of the Covenanters was commanded by Elcho;

the left by Sir James Scott, and the centre by the

Earl of Tullibardine. Montrose drew up his men three

deep, with as long a front as possible. An attack by a

party of Elcho’s horse, under Lord Drummond, was

easily beaten off. Then Montrose’s line

advanced to the attack. It was made in the traditional

Highland manner, which was so often to prove

successful against regular troops. The assailants

advanced to within short range; then such of them as

had muskets fired a volley; then they rushed in and

attacked with the broadsword; The peaceable burghers

of whom the Covenanting army was largely composed had

little chance in a hand-to-hand conflict with savage

mountaineers. They broke and fled in utter rout. The

Rev. John Robertson, one of the ministers of Perth,

describes the sorry plight of some of the citizens who

reached the town, "all forefainted and bursted with

running, insomuch that nine or ten died that night in

town without any wound." "The Provost came into one

house," he says, "where there were a number lying

panting, and desired them to rise for their own

defence: They answered—their hearts were away—they

would fight no more although they should be killed."

The number of killed on the Covenanting side is

variously stated; Wishart, Montrose’s chaplain and

chronicler, gives it as 2000. On the same day Montrose

entered Perth as a victor. There he was able to

provide his army with clothing, abundance of arms and

ammunition, and six pieces of cannon.

At the

head of "a pack of naked runagates," as Baillie calls

them, Montrose had now defeated an immensely superior

force in the field, and had captured one of the chief

towns of the kingdom. It was no part of his policy to

remain there. After a victory a Highland army always

began to melt away, the men returning homewards to

secure their plunder and save their harvest. In any

case an open town could not be defended against a

regular siege by Argyll’s army. Elcho had retreated to

Aberdeen, and Montrose resolved to follow him up.

He

marched northwards through Angus and the Mearns, being

joined on the way by the old Earl of Airlie and a

considerable force of the Ogilvies and their friends.

On reaching the Dee he made no attempt to force the

bridge at Aberdeen, but marched up the right bank of

the river and forded it at the Mills of Drum. On the

night of September 11 he camped at Crathes. On the

13th the Covenanters marched out of Aberdeen to meet

him. Their force, which was commanded by Lord Balfour

of Burleigh, consisted of some 2000 foot and 500

horse. Montrose had about 1500 foot and only 44

mounted men. The armies met a little to the west of

the city, "between the Craibstane and the Justice

Mills," where the Hardgate now runs. After a four

hours’ engagement the Covenanters broke and fled.

Montrose’s Irish troops behaved with great spirit in

action, but after the battle they seem to have got

badly out of hand, and horrible atrocities were

committed by them in Aberdeen. "The men that they

killed," says Spalding, "they would not suffer to be

buried, but tirred (stripped) them of their clothes,

syne left their naked bodies lying above the ground.

The wife durst not cry or weep at her husband’s

slaughter before her eyes, nor the mother for the son,

nor daughter for the father, which if they were heard

then they were presently slain also. Nothing," he

says, "was heard but pitiful howling, crying, weeping,

mourning through all the streets."

Montrose left Aberdeen on September 16. He had hoped

for a large accession of strength in the Gordon

country, but found himself disappointed in this,

apparently through the personal jealousy of the

Marquis of Huntly. With the force at his command he

could not meet Argyll’s army in the field, so during

the following weeks we find him moving rapidly from

place to place in the Highlands, on Speyside, in

Badenoch, in Atholl, down in Angus, and again up in

Aberdeenshire. Argyll had marched northward from Perth

on September 14 with a force of some 3000 foot and two

regular cavalry regiments, besides ten troops of

horse. After following Montrose all over the country

he came up with him at Fyvie on October 28.

Notwithstanding the great disparity of’ forces

Montrose gave him battle. Argyll was repulsed, and

allowed Montrose to retreat into Strathbogie. He

himself returned to Edinburgh, "where," says Spalding,

"he got but small thanks for his service against

Montrose." Thence he withdrew to his castle at

Inverary.

Montrose again marched down through Badenoch into the

Atholl country. Notwithstanding his military successes

his prospects did not seem very cheering. He had not

succeeded in raising anything like the force he

expected from among the clans, and many of his Lowland

officers had left him. Old Lord Airlie and his two

sons alone remained faithful throughout. A descent

upon the Lowlands was thought of and abandoned. Then

was conceived the most daring and brilliant operation

of the whole campaign—one of the most daring in all

military history. This was to attack Argyll in his own

impregnable fortress of Inverary. A blow struck there

would shake the Covenanting power to its very

foundation, and would gather to the royal standard the

many enemies of the well-hated race of Campbell. A

forced march in mid-winter over the Argyllshire

mountains was only possible to such an army as

Montrose’s. It was effected with startling rapidity.

Montrose passed like a meteor from Blair Atholl along

Loch Tay, through Breadalbane and Glenorchy, ravaging

the Campbell lands as he went. Argyll fancied himself

absolutely secure, believing as he did that Inverary

was quite inaccessible to an army from the east. He

was rudely undeceived. Early in December some

shepherds arrived from the hills with the news that

Montrose was close at their heels. Argyll had just

time to save his own skin. He escaped by sea to

Roseneath. For six weeks, till near the end of January

1645, Montrose’s troops pillaged the Campbell country

at their pleasure.

His

next move was to march northward by Glencoe and

Lochaber, with the object of attacking Inverness,

which was held by a Covenanting force under Seaforth.

By this time he had been joined by many of the western

chiefs. At Kilcummin, now Fort Augustus, on January 29

and 30, a bond promising support to the royal cause

was subscribed by the chiefs present. Among the

signatures appear those of Maclean of Duart, Maclean

of Lochbuy, Macdonald of Keppoch, Macdonald younger of

Glengarry, the Captain of Clanranald, the Tutor of

Struan, the Tutor of Lochiel, the Macgregor, the

Macpherson, and Stewart younger of Appin. It was

immediately after the signature of this bond that the

news reached Kilcummin that Argyll was again on

Montrose’s track at the head of some 3000 men, partly

his own clansmen and partly some of the troops which

had been recalled from England. With these he was

ravaging Lochaber. Montrose’s resolution was at once

taken. He made one of his astonishing forced marches

over Corryarrack, and down Glen Roy, and on the

morning of February 2 swooped on Argyll at Inverlochy.

We have

Montrose’s own account of this famous march and fight,

written to the King the day after the batttle:-

"My march was

through inaccessible mountains," he says, "where I

could have no guides but cowherds, and they scarce

acquainted with a place but six miles from their own

habitations. If I had been attacked with but one

hundred men in some of these passes I must have

certainly returned back, for it would have been

impossible to force my way, most of the passes being

so strait that three men could not march abreast. I

was willing to let the world see that Argyle was not

the man his Highlandmen believed him to be, and that

it was possible to beat him in his own Highlands.

"The

difficultest march of all was over the Lochaber

mountains, which we at last surmounted, and came upon

the back of the enemy when they least expected us,

having cut off some scouts we met about four miles

from Inverlochy. Our van came within view of them

about five o’clock in the afternoon, and we made a

halt till our rear was got up, which could not be done

till eight at night. The rebels took the alarm and

stood to their arms, as well as we, all night, which

was moonlight and very clear. There were some few

skirmishes between the rebels and us all the night,

and with no loss on our side but one man. By break of

day I ordered my men to be ready to fall on upon the

first signal, and I understand since, by the

prisoners, the rebels did the same. A little after the

sun was up both armies met, and the rebels fought for

some time with great bravery, the prime of the

Campbells giving the first onset, as men that deserved

to fight in a better cause. Our men having a nobler

cause did wonders, and came immediately to push of

pike and dint of sword after their first firing. The

rebels could not stand it, but after some resistance

at first began to run, whom we pursued for nine miles

together, making a great slaughter, which I would have

hindered if possible, that I might save your Majesty’s

misled subjects. For well I know your Majesty does not

delight in their blood, but in their returning to

their duty. There were at least fifteen hundred killed

in the battle and the pursuit, among whom there are a

great many of the most considerable gentlemen of the

name of Campbell, and some of them nearly related to

the Earl. I have saved and taken prisoners several of

them, that have acknowledged to me their fault and lay

all the blame on their chief. Some gentlemen of the

Lowlands that had behaved themselves bravely in the

battle, when they saw all lost fled into the old

castle, and upon their surrender I have treated them

honourably and taken their parole never to bear arms

against your Majesty. . . . We have of your Majesty’s

army about two hundred wounded, but I hope few of them

dangerously. I can hear but of four killed, and one

whom I cannot name to Your Majesty but with grief of

mind—Sir Thomas Ogilvy, a son of the Earl of Airlie,

of whom I writ to your Majesty in my last. He is not

yet dead, but they say he cannot possibly live, and we

give him over for dead. Your Majesty never had a truer

servant, nor there never was a braver, honester

gentleman."

The defeat at

Inverlochy was a crushing blow to the Covenanters. The

power of the Campbells was humbled to the dust. From

the safe refuge of a boat on Loch Fyne Argyll had

witnessed the rout of his army and the slaughter of

his kinsmen. Montrose thought that he would shortly

have Scotland at his feet, and that he would ere long

cross the Border at the head of a victorious army. "I

am in the fairest hopes," he writes to Charles, "of

reducing this kingdom to your Majesty’s obedience. And

if the measures I have concerted with your other loyal

subjects fail me not, which they hardly can, I doubt

not before the end of this summer I shall be able to

come to your Majesty’s assistance with a brave army,

which, backed with the justice of your Majesty’s

cause, will make the rebels in England, as well as in

Scotland, feel the just rewards of rebellion. Only

give me leave, after I have reduced this country to

your Majesty’s obedience, and conquered from Dan to

Beersheba, to say to your Majesty then, as David’s

General did to his master, ‘Come thou thyself lest

this country be called by my name.’"

Montrose did not

rest upon his laurels. After his victory he again

marched northward, up what is now the line of the

Caledonian Canal. The Covenanting army at Inverness

melted away at his approach. On February 19 he reached

Elgin. Here he received a welcome accession of

strength; he was joined by a force of the Gordons

under Lord Gordon, Huntly’s eldest son, and Lord Lewis

Gordon.

His object now

was to strike at the Lowlands. The road to the south

was blocked by a force of the troops who had been

recalled from England, commanded by General William

Baillie of Letham, an old soldier of Gustavus

Adolphus’s, and a much more formidable antagonist than

the amateur commanders whom as yet Montrose had had

opposed to him. There was also a force of some 600

horse under Sir John Hurry, a soldier of fortune who

changed sides four times during the troubles.

From Elgin,

Montrose marched by Huntly and Kintore to Stonehaven,

plundering the lands of the north-country Covenanters

as he went. Near Fettercairn he came into touch with

Hurry’s cavalry, who retreated before him. Baillie

well knew the peculiar weakness of a Highland army. He

determined to avoid an engagement as long as possible,

knowing that every day of waiting and manoeuvring

would weaken his enemy by desertions. Wishart tells a

characteristic story of the two commanders. The armies

had come face to face with each other at Coupar-Angus,

on opposite banks of the Isla. Neither could cross the

river without serious loss if the passage was

disputed. Montrose, in the spirit of old-world

chivalry, sent Baillie a challenge by a trumpeter. He

asked permission to cross the river unopposed, or if

the Covenanting general preferred he might himself

cross to Montrose’s side, if he would pledge his

honour to fight without further delay. The old

campaigner drily replied "that he would mind his own

business himself, and would fight at his own pleasure,

and not at another man’s commands."

At last Baillie

retired towards Fife, without ever having come to an

action. Montrose marched westward and occupied Dunkeld.

The way to the south was now open, but Baillie’s

Fabian policy had succeeded. Montrose’s army had

melted down to some 800 men. With such a force it was

out of the question to invade the Lowlands. Montrose’s

information was that the whole of Baillie’s force was

now on the west side of the Tay. He determined to make

a dash on Dundee. Early in the morning of April 3 he

started from Dunkeld. Dundee was reached next day, and

occupied with little resistance. Montrose, however,

had been misinformed as to Baillie’s movements, and he

just escaped irreparable disaster. His men had

scattered through the town in quest of drink and

plunder, when news came that Baillie and Hurry, with

3000 foot and 800 horse, were within a mile of the

town. Montrose managed to collect his troops—a notable

example of his personal power of command—and escaped

from the east gate of the town just in time. Baillie

followed close at his heels during the night, hoping

to corner him against the sea at Arbroath. Montrose,

however, doubled back, slipped round Baillie’s rear,

crossed the South Esk at Careston Castle at sunrise,

and succeeded in reaching the Grampians. It was a

wonderful achievement; the men had been marching and

fighting for three days and two nights without food or

sleep, and were half dead with hunger and fatigue.

Wishart says that he often "heard officers of

experience and distinction, not in Britain only, but

also in Germany and France, prefer this march of

Montrose to his most famous victories."

As we have seen,

Montrose’s army had dwindled to a mere handful. Lord

Lewis Gordon, always untrustworthy, had deserted, and

had taken many of the Gordons with him. There was

nothing to be done but to retire again to the North

and endeavour once more to build up an army. Baillie

was watching the Highlands from Perth, and Hurry had

gone north to Inverness to collect forces for an

attack on the Gordons. Lord Gordon had gone home to

his own country to raise further levies, and, if

possible, to bring back the men who had been carried

off by Lord Lewis.

After picking up

some recruits in Perthshire, Montrose found his way

into the Mar country. There he met Lord Gordon at the

head of 1000 foot and 200 horse. He had already been

joined by Lord Aboyne, who, with a few horsemen, had

escaped from beleaguered Carlisle. By a daring raid on

Aberdeen Aboyne secured a much-needed supply of

gunpowder. Then it was decided to attack Hurry.

Montrose marched

over the hills by the route which is now followed by

the road from Cocksbridge to Tomintoul, and then down

Strathspey. Hurry advanced from Inverness to meet him.

Near Elgin the armies came into touch. Hurry retired

on Inverness, closely followed by Montrose. At

Inverness the Covenanting army received a large

accession of strength, being joined by the Earl of

Seaforth, who had again changed sides, the Earl of

Sutherland, and a force of the Frasers. This placed

Hurry at the head of nearly 4000 men, of whom 400 were

cavalry. Montrose’s force did not amount to more than

1500 foot and 250 horse, the latter consisting chiefly

of the Gordons. Hurry turned upon his enemy, secure of

victory. On the evening of May 8 Montrose reached the

village of Auldearn, on the road between Forres and

Nairn, some two miles east of the latter. Here he was

attacked by Hurry on the following morning.

Montrose took up

his position along the ridge crowned by the village of

Auldearn, at right angles to Hurry’s line of advance.

The village itself was the centre of his position. It

was only occupied by a handful of men, enough to lead

the assailants to believe that it was held in force.

Alastair Macdonald with 400 Irish was posted on the

right, in a position strongly defended by dykes and

ditches. Montrose himself was on the left, behind the

ridge, with the remainder of the infantry and the

whole of the cavalry, the latter under Lord Gordon.

Hurry’s right wing was commanded by Campbell of Lawers,

his left by Captain Drummond; he himself remained in

the rear in command of the reserves.

The royal

standard had been entrusted to Macdonald, with the

object of causing Hurry to believe that Montrose

himself was stationed on the right, and if possible of

inducing him to make his main attack there. The ruse

was successful. Hurry sent the bulk of his force to

attack the Irish. Macdonald in an evil moment allowed

himself to be drawn from his strong position, and

narrowly escaped disaster, though

he himself performed

Homeric feats of personal prowess. "Some of the

pikemen," says Wishart, "by whom he was hard pressed

again and again pierced his target with the points of

their weapons, which he mowed off with his broadsword

by threes and fours at a sweep." News was sent to

Montrose that the right wing was routed. Wishart

describes what followed. "To prevent a panic among his

men at the bad news, with admirable presence of mind

he (Montrose) at once called out, ‘Come, my Lord

Gordon, what are we waiting for? Our friend Macdonald

on the right has routed the enemy and is slaughtering

the fugitives. Shall we look on idly and let him carry

off all the honours of the day?" With these words he

hurled his line upon the enemy. The shock of the

Gordons was irresistible. After a brief struggle

Hurry’s horse wavered, recoiled, wheeled, and fled,

leaving their own flanks naked and exposed. Though

deserted by the horse, the infantry, being superior in

numbers and much better armed, stood their ground

bravely until Montrose came to close quarters and

forced them to fling down their arms and save

themselves by flight." Having thus disposed of Hurry’s

right wing, Montrose turned upon those who were

assailing Macdonald’s position. "The horse fled

headlong, but the foot, mostly veterans from Ireland,

fought on doggedly, and fell man by man almost where

they stood." The victory was complete. The Covenanters

were pursued for miles with tremendous slaughter. The

whole of their colours, baggage, and ammunition were

captured by the Royalists.

A week

before the battle of Auldearn, Baillie, whom we left

at Perth, had broken into the Atholl country, where

Blair Castle was held for the King. On hearing of the

battle he marched northward, and at Strathbogie was

joined by Hurry with the remains of his defeated army.

Montrose, weakened by the desertion of many of his

Highlanders, was in no haste to fight, and withdrew up

Strathspey into Badenoch. Lord Lindsay was collecting

a force in Forfarshire with the object of advancing

against Montrose from the south. An attempt on

Montrose’s part to attack him was frustrated by the

desertion of the bulk of the Gordon horse. Montrose

retired into Strathdon, and took up his position at

Corgarff Castle, there to await events.

By the

end of June he was once more in a position to fight.

Lord Gordon and Colonel Nathaniel Gordon had succeeded

in bringing back most of the Gordons, and Alastair

Macdonald had brought in more men from the Highland

glens. Montrose was at the head of some 2000 men.

Baillie, on the other hand, had been seriously

weakened by the transfer to Lindsay’s force of over

1000 of his best men, in exchange for 400 recruits. He

was still in the North, where he had been ordered by

the Estates to lay waste Huntly’s country.

Montrose accordingly endeavoured to bring Baillie to

an engagement at Keith. Baillie, who occupied a strong

position there, was not to be drawn. Montrose retired

south towards the Don. Baillie had to follow him or

leave the road to the Lowlands open. Montrose crossed

the Don at Alford and took up his position on a ridge

of high ground to the south of the river. There

Baillie attacked him on July 2.

The

forces were nearly equal in respect of numbers; the

Covenanters had rather the best of it in cavalry.

Montrose’s force was drawn up along the crest of the

ridge with the cavalry on the flanks, under Lord

Gordon and Aboyne. Part of the force was concealed

behind the ridge. Baillie forded the Don about half a

mile in front of Montrose’s centre, crossed a piece of

boggy ground near the river-side, and advanced up the

slope of the hill to the attack. He was not waited

for. The horse on Montrose’s right wing, headed by

Lord Gordon and supported by a body of Irish

musketeers, charged his cavalry and drove it back in

confusion. Then the main body rushed down and fell on

with the claymore. The Covenanting infantry made a

brave stand, but soon they too broke and fled.

Montrose had won another decisive victory. Young Lord

Gordon was struck down in the moment of victory by a

shot from one of the fugitives. His death was a

terrible loss to the army and to the royal cause in

Scotland. "Montrose," says Wishart, "could not

restrain his grief, but mourned bitterly as for his

dearest and only friend."

The

victory at Alford cleared Montrose’s way to the south.

Six days after the battle the Covenanting Parliament

met at Stirling and resolved to levy a new army from

the Lowland counties. It was to assemble at Perth on

July 24. The unlucky Baillie, foreseeing certain

disaster, twice tendered his resignation, but it was

not accepted, and to make matters worse he was

subjected to the control of a military committee whose

members could not even agree among themselves.

Montrose in the meantime was receiving great

accessions of strength. The news of his victory and

the prospect of a descent on the Lowlands brought

crowds of clansmen to his standard—Macleans from the

west, Macdonalds of Clanranald and Glengarry,

Macgregors, Macnabs, Macphersons from Badenoch,

Farquharsons from Braemar, and a contingent of Atholl

men under Patrick Graham of Inchbrakie. Towards the

end of July he marched south from Fordoun, where he

had awaited his reinforcements, and appeared in the

neighbourhood of Perth. He was still expecting further

reinforcements and had no desire to fight a serious

battle just yet. A few skirmishes took place, in which

the Covenanters always had the worst of it. Early in

August he was joined at Dunkeld by a strong force of

the Gordons, and by eighty horsemen of the Ogilvies

under the brave and ever loyal old Earl of Airlie. All

was now ready for the advance into the Lowlands.

Montrose marched down through Kinross, descended the

vale of the Devon, destroyed Argyll’s castle of Castle

Campbell near Dollar, and crossed the Forth at the

Fords of Frew. On August 14 he reached Kilsyth.

Baillie

had to follow him. He crossed the Forth at Stirling

Bridge, and on the night of the 14th he camped at

Hollinbush, about two and a half miles east of

Montrose’s position. According to Wishart his force

consisted of 6000 foot and 800 horse, while Montrose

had 4400 foot and 800 horse. The Covenanting force,

however, consisted of hastily raised and untrained

levies, mostly Fifeshire men who could with great

difficulty be persuaded to serve out of their own

shire, and their commander was sorely hampered by the

Committee which had been set over him, and which

included among its members Argyll, whom Montrose had

beaten at Inverlochy, Elcho, whom he had beaten at

Tippermuir, and Balfour of Burleigh, whom he had

beaten at Aberdeen.

The

Committee imagined that Montrose was anxious to avoid

an engagement. Exactly the reverse was the case. A

Covenanting force of 1500 men had been raised in

Clydesdale by the Earl of Lanark; they were

approaching from the west, and were now within 12

miles of Kilsyth. Montrose’s one object was to fight

Baillie before Lanark could come up. He drew up his

men in an open meadow a little to the east of Kilsyth.

On the morning of the15th the Covenanters advanced to

attack him over rugged ground.

To the

north of Montrose’s position there was a hill which

commanded his left flank. It appeared to the Committee

that if this could be occupied they would be in a

position to cut off Montrose’s expected retreat. They

accordingly directed Baillie to move to his right and

take possession of the hill. To try to execute a flank

movement across the front of an active and determined

enemy was simply fatuous, and Baillie knew it, but the

Committee insisted on their point. The fatal movement

was begun. Montrose saw what was aimed at and

despatched a force under Adjutant Gordon to hold the

hill. A glen with a burn running through it had to be

crossed by the Covenanters. The obvious result

happened. The straggling column was charged in flank

by the Macleans and Macdonalds and cut in two. Its

head was attacked on the hill by Gordon, who was soon

strongly reinforced, and was cut to pieces. The rout

became general, and the fields were soon covered with

terrified fugitives. The pursuit was remorseless and

the slaughter frightful; Wishart says that 6000 of the

Covenanters perished. Some of their leaders took

refuge in Stirling Castle; some escaped by sea; Argyll

went on board ship at Queensferry and reached

Newcastle.

Kilsyth

was Montrose’s crowning victory. Baillie had told the

Committee that the loss of the day would mean the loss

of the kingdom, and he was right. The King’s

Lieutenant now had Scotland at his feet. The

Covenanting leaders fled or submitted; the western

levies dispersed to their homes. The imprisoned

Royalists were set at liberty. The towns opened their

gates; Edinburgh surrendered in the most abject

manner. It seemed that the royal authority was

completely restored, and Montrose, in the King’s name,

summoned a meeting of Parliament for October.

His

immediate object, however, was to go to the help of

the King in England. He had assured Charles that he

would soon cross the Border at the head of 20,000 men.

He had imagined that the Lowlanders, once freed from

the tyranny of Argyll and the Kirk, would flock to his

standard, and that he would continue his career of

victory till the royal cause was- triumphant

throughout the island.

He was

bitterly undeceived. Mr Gardiner comments with justice

on the astonishing absence of all grasp on the

concrete facts of politics, which in Montrose was

coincident with the most intense realisation of the

concrete facts of war. He entirely misjudged the

temper of the Lowlands. The sympathies of the common

people were all on the side of the Kirk; probably most

of them desired nothing more than to be left in peace

by both parties to get their harvests in; in any case

they hated and feared the Highlander and the Irishman,

who had won Montrose’s victories. Montrose entirely

failed to raise a Lowland army; what recruits he did

get were almost all of the upper classes. On the other

hand, the army of Kilsyth was rapidly melting away.

The clansmen had no fancy to be led south of the

Tweed; they were disappointed in not getting the

plunder of the Lowland towns; they all found pressing

reasons of one kind or another for returning to their

homes. The Macdonalds left in a body with Alastair at

their head. Montrose marched southward from Bothwell

in the beginning of September. Before he reached the

Border he found himself in command of a mere handful

of men.

In the

meantime a formidable antagonist was approaching from

the south. David Leslie, at the head of 4000 cavalry,

had been detached from the Scottish army before

Hereford, and was making for the Border with all

possible speed. In the first week of September he

crossed the Tweed at Berwick. He continued his march

towards Edinburgh, expecting to fight Montrose in the

Lothians. When in East Lothian he heard that his enemy

was at Kelso. He turned to the west, marched down by

Gala Water, and on the night of September 12

encamped at the village of Sunderland.

Montrose was at Selkirk. The greater part of his army

was encamped on Philiphaugh, on the north side of the

Ettrick. The number of men with him is variously

given. According to Mr Gardiner, he had only 500 of

his faithful Irish and some 1200 horse, of whom only

150, under Lord Airlie and Nathaniel Gordon, took part

in the fight. He was badly served by his cavalry

scouts. On the morning of the 13th, favoured by a

thick mist, Leslie with his whole force succeeded in

surprising the doomed Royalists. With such disparity

of force the battle was a mere rout. A brief and

gallant stand was made in vain. Montrose and a few

others succeeded in saving themselves by flight; most

of the men were slain or taken prisoners. The

Covenanters butchered their prisoners in cold blood.

Among the camp followers were some 300 Irish women,

the wives of the soldiers, with their infant children.

These shared the fate of their husbands and fathers.

Most of the prisoners of rank perished on the

scaffold.

The

crushing disaster of Philiphaugh ended Montrose’s

brilliant and fruitless career of victory. Ever since

the battle of Naseby (June 14, 1645) the royal cause

in England had been hopeless. It was now equally

hopeless in Scotland. Montrose escaped to the

Highlands, where he attempted in vain to reconstruct

an army. In May 1646 the King surrendered himself to

the Scots army in England. Shortly afterwards he

commanded Montrose to disband his forces. Montrose

himself escaped to Norway in September. "His high

enterprise had failed," says Mr Gardiner. "No skill of

warrior or statesman could deal successfully with a

problem the solution of which depended on the one hand

upon the wisdom of Charles, and on the other on the

discipline of the Gordons and of the Highland clans."

Four

years later Montrose again appeared in arms in

Scotland. The last act of his drama is brief and

tragic. The execution of Charles I. took place on

January 30, 1649. The dominant faction in Scotland

acknowledged Charles II. as his successor in the

kingdom of Scotland, and proceeded to open those

negotiations which led to his appearance in Scotland

for a brief period in the character of a "Covenanted

King." Montrose, filled with grief and rage by the

death of his master, was burning with desire to avenge

his blood and to restore his son to the crown.

Charles, while actually in treaty with the

Covenanters, granted to Montrose a commission

authorising him to solicit help from the Northern

Powers and to effect a descent on Scotland. Montrose

landed in Orkney in March 1650 with some 700 men.

There he remained some weeks, and was joined by about

800 men from the islands. With this force he crossed

into Caithness. A strong force under David Leslie was

sent north to meet him. On April 27 he was attacked

and defeated at Carbisdale by a detachment under

General Archibald Strachan. He escaped wounded from

the fight, and a few days later was captured by

Macleod of Assynt and handed over to the Covenanting

general.

His

fate was now sealed. He was sent as a prisoner to

Edinburgh. After the battle of Inverlochy the doom of

forfeiture and death had been pronounced against him

by the Estates, and by the Church he had been

"delivered into the hands of the devil." No trial was

needed. On May 21, 1650, he was put to death at the

Cross of Edinburgh with every circumstance of insult

and degradation.

With

the justice of his cause we are not here concerned,

nor with the vindication of his political conduct. As

to the latter, his own point of view is clear enough.

"The Covenant which I took," he said to the

Covenanting ministers the day before his death, "I own

it and adhere to it. Bishops, I care not for them. I

never

intended to advance their interest. But when the King

had granted you all your desires, and you were every

one sitting under his vine and under his fig-tree,

that then you should have taken a party in England by

the hand, and entered into a League and Covenant with

them against the King, was the thing I judged it my

duty to oppose to the yondmost." His military

reputation is beyond question. Dr Hill Burton speaks

of it depreciatingly, on the ground that "he was

defeated on the only occasion when he met face to face

with another commander of repute." So he was, when the

"other commander of repute" outnumbered him five to

one. The story of his campaign speaks for itself. He

was one of the greatest commanders of Highland troops

that ever lived, and in personal loyalty and bravery

he has left an illustrious example to all ages.

The battles of

Dunbar and Worcester were followed by the rule of the

Commonwealth in Scotland. One more attempt was made

for the King in the North. In

1653 a force was raised in

the West Highlands by the Earl of Glencairn, who was

joined by Glengarry, Lochiel, and Atholl. His idea,

apparently, was to emulate the feats of Montrose, but

he was not the man to do it. The command of the force

was taken over by General Middleton, who arrived from

England, having escaped from the Tower. He held a

commission as generalissimo of the King’s forces in

Scotland. An army of 3000 men, under Monk and General

Morgan, marched northward against the Royalists.

Morgan met and defeated them on the banks of Lochgarry.

Lochiel held out in the west for some time; but

ultimately submitted. There was no more important

warfare in the Highlands for a generation. |