hill-shading wherever the streaks and patches of blue

leave a tract of dry land big enough to build a mountain upon. Argyllshire,

Inverness-shire, Perthshire and Dumbartonshire, as presented by the maker of

maps, may be compared to the colours of some fighting regiment, after half a

century of arduous campaigning, blackened by powder and rent by bullet. This

is putting it poetically, but a more prosaic comparison would be to say that

these West Highlands on the map are like a cabbage-leaf devoured by

caterpillars.

Such a wild and picturesque district is a very

Paradise for the tourist, but hitherto this "Land of Mountain, Moor and

Loch" has been remarkably difficult of access. It is traversed diagonally by

the chain of lochs that form the. Caledonian Canal, cutting through

Argyllshire and Inverness- shire from the Island of Mull to the Moray Firth,

like the straight slash of a knife, and the traveller has been enabled to

skirt these rugged shires by steamer, while he has also been able to

penetrate tar into Argyll and Dumbarton by the great southern lochs; but

where the paddle-wheel ceased to revolve there has been no locomotive to

take up the running. From the stopping-points of the steamers, there have

been a few coach routes, but these have covered only an infinitesimal part

of this marvellously beautiful country, and hitherto the land west of the

Grampians, from Lochaber, south to the sea, has been left almost alone to

the pedestrian or cyclist of untiring muscle. Hitherto one railway alone has

intruded amongst these glorious glens, these frowning peaks and gleaming

lochs—the line that runs from Kuhn in Perthshire, almost due west, bisecting

the Argyllshire Highlands. But nearly all the passengers by this route have

been making straight for the terminus at Oban, and in the short run after

the Grampians are crossed, have had nothing more than a glimpse of the

scenery now completely opened up from South to North.

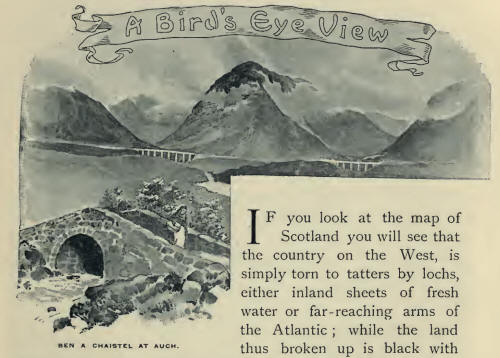

The West Highland Railway, now completed, breaks fresh

ground from start to finish of its hundred-mile run; carrying the traveller

through what is, perhaps, the most sublime and characteristic portion of

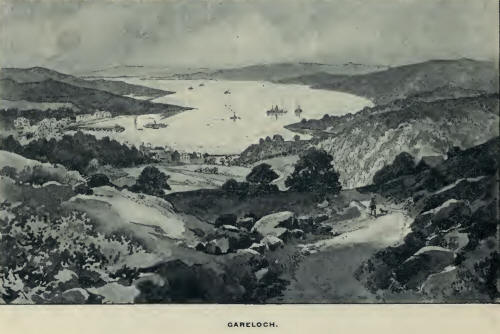

Scotland. Taking up at Helensburgh, which lies at the mouth of the Gareloch,

an uncompleted end of the North British Railway, it winds northwards along

the base of the Grampians to Inverlair, whence it strikes westwards through

Lochaber to Fort William on Loch Linnhe, which with a branch to Banavie,

makes connection with the Caledonian Canal, and brings within the reach of

the traveller the most tempting possibilities in the way of circular tours.

Now in Dumbartonshire, now in Perthshire, now in Argyllshire, now in

Perthshire again, now in Inverness-shire, it never for one moment meets the

prosaic: the panorama of landscape that passes before the carriage windows

changing almost every minute, into more and more bewitching visions of

infinite variety. As the Irish navy engaged on the construction of the line

observed, "Sure, it's the most amphibious country ever seen by the naked

eye"—so many sheets of deep blue water break upon the sight as the train

sweeps round each curve, that to the non-engineering traveller, it seems as

if a new Caledonian Canal might have been constructed almost as easily as a

railway; while the hills are piled on each other in such multitudinous

profusion that the opening out of each new vista of towering peaks fairly

intoxicates an artist with delight.

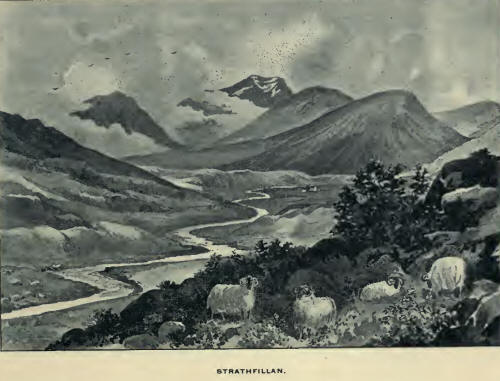

The scenery may be divided roughly into four sections.

From Helensburgh to Ardlui the line hugs in succession the shores of three

great lochs—Gareloch, Loch Long, and Loch Lomond—which cleave their way

through grand mountain barriers ; from Ardlui to Gortan, it threads its

course along a bewildering maze of stupendous crags from Gortan to Rannoch,

it traverses the great Moor of Rannoch, which has no parallel in Britain ;

and from Rannoch to Fort William it passes through a country that combines

all the features of the previous stretches, loch, moor and glen, overhung-

by vast eminences scattered over the land with lavish prodigality— Ben

Lomond, Ben Irne, Ben Vane, Ben Voirlich, Ben More, Ben Doran, and a phalanx

of other mountains, culminating in mighty Ben Nevis. Never was there a

railway that less disfigured the country through which it passed. Like a

mere scratch on the mountain slopes, it glides from valley to valley,

unobtrusive as a sheep path, and not even John Ruskin would regard it as a

desecration of the Highland solitudes. Along the course of this West

Highland Railway little evidence of cultivation meets the eye of the

superficial observer; and yet many of the best sheep farms of Scotland—in

some instances feeding not less than 20,000 head of the finest black-faced

sheep of the country—are found on the lands traversed by it. It is a land of

sport, the home of the deer, the grouse and the white hare, while the

streams abound with trout, and those who know it will cease to wonder why

the old clansmen who inhabited those bare yet beautiful glens sought so

often and so successfully to make the cattle of the Lowlands their own. Up

to Ardlui, houses are far apart, but still one feels that the country is

inhabited; north of that place houses are few, and when a dwelling-place

appears it is generally a low thatched hut, and you have to look twice

before asserting dogmatically which is the house and which is the haystack.

If ever there was a railway which was so evidently a

railway for the tourist and holiday-seeker, it is the West Highland.

Manufactures there are none, but the railway will give to agriculture and

farming, facilities hitherto unknown, and there will, without doubt, be an

increased traffic in sheep and cattle, which will find a new outlet to the

South from the districts converging on Spean Bridge and at other points of

the line. Industries will doubtless grow, now that the railway is opened,

but goods traffic will require some years to develop, although the

well-known "Long John" whiskies of Fort William will contribute something.

It opens up a world hitherto known only to the sportsman and to the

comparative few who, with abundant leisure and means, could penetrate the

magnificent country through which it passes. Beyond this, the extensive

country which is brought within

easy access of the commercial metropolis of Scotland

will be developed by the industry and enterprise, characteristic of the

industrious and intelligent community which has given Glasgow so prominent a

place among the cities of the Empire. Not only does it throw open a new land

of promise, as we have shown, but it will shorten by upwards of an hour the

journey between Edinburgh or Glasgow and Oban —a watering-place that

requires no introduction to popular favour. Along the line, coach roads

strike off to right and left, taking the traveller through the many

interesting districts into which the railway runs—the "Rob Roy" country, the

"Lady of the Lake" country, and the ever famous Glencoe—making connection

with steamboat services on the lochs, and transporting him whither he will,

by land or by water, over this happy hunting ground of the tourist. Now that

the bridle track and sheep path have been supplemented by the iron-way, in

such an embarrassment of alluring alternatives, the difficulty is not to

find a route, but to select one, for the West Highland Railway emphatically

forms perhaps the greatest of the great "show-routes" of Britain.

|