"IT'S a far cry to Lochaber," but in

these days of luxurious locomotion the traveller is carried from London into

the very heart of the 'Western Highlands with almost as little exertion as

if he were going from the City to his suburban home. Leaving late in the

evening, he finds the long journey accomplished in the course of the night

and early morning, and the through carriages of the great trunk lines are

nowadays so comfortable that it is simply a case of being whisked along at

lightning speed in bed or in an armchair. For those who prefer to travel by

day, the beauty of the scenery, and the interest attaching to the places

'which are passed on the railway route to Edinburgh or to Glasgow, renders

the trip a strong attraction in itself, although it cannot compete with the

fascination of the Highland tour that has drawn them to the North, and which

culminates after the two great Scottish cities are passed.

The EAST COAST route from the

Metropolis to Scotland- 393 miles to Edinburgh, whence it is a run of 47

miles to Glasgow, which lies at the door of the Western Highlands— links

together three of the great railways; the Great Northern, from King's Cross

to Doncaster; the North Eastern, from Doncaster to Berwick-on-Tweed ; and

the North British, from Berwick to Edinburgh and Glasgow. The ordinary

carriages on this route are well nigh perfection in all the appliances for

the comfort of the traveller, while corridor dining saloons and sleeping

cars bring in the luxuries of railway transit. Through travellers may break

their journey at Peterborough, Grantham, York, Durham, Newcastle, Berwick,

or any station further north on the direct route.

On speeding from under the roof of

King's Cross terminus, the northern suburbs are traversed, London being left

behind when the Alexandra Palace is passed. Hatfield House, close to the

line, is next noted. Soon after, there is seen on the left Knebworth House,

the seat of Lord Lytton, and, passing through Hitchin and Biggleswade, we

reach Huntingdon (58 miles from London). The famous fen country is now

entered, and level plains are traversed, wrested by skilful drainage and

tillage, from Whittlesea Mere. Peterborough (76k miles), which may be called

the capital of the fens, presents a striking appearance, rising with its

noble cathedral out of the flat lands around it. The cathedral is a

magnificent specimen of Gothic architecture, and is recognised as being one

of the most impressive ecclesiastical piles in Great Britain.

After a short stoppage, the train

resumes its course, and at Essendine, Lincolnshire is entered. Soon after,

the handsome tower of Caseby Church is seen on the right, and a little

beyond we see Grimsthorpe Castle, the beautiful residence of Baroness

Willoughby d'Eresby. Soon after passing Corby, and the church of Burton

Coggles on the right, the highest point of the Great Northern system is

reached, about 400 feet above the sea-level. We are now approaching Grantham

(105 miles), which is the first stopping-place of the "Flying Scotchman" and

the other famous East Coast expresses. The ordinary main line trains stop

here for a few minutes. Grantham has a striking parish church in the Gothic

style, with a crocketed spire 280 feet in height; but the town is mostly

notable for the gigantic ironworks of Messrs. Richard Hornsby & Sons, which

cover nearly seventeen acres and employ about I,5oo hands.

Newark (120 miles), the next

prominent point, is a town that has had a large part in the making of

history. Its ancient castle has seen rough work since its foundations were

laid by the Saxons, and in the civil war of the seventeenth century it was

thrice besieged by the Roundheads, surrendering at last to the Scotch army

of the Parliament. Leaving Newark behind, we pass through one of the finest

fruit-growing districts in England, the country on both sides being almost

continuous orchards. Passing through Retford (138 miles), we come to Scrooby,

a famous meeting-place of the "Pilgrim Fathers" before they sought asylum in

America: At Doncaster (156 miles)—a name familiar to everybody—attention is

attracted by the fine parish church (a splendid example of pointed

architecture, but dating only from the middle of the present century), with

a tower 170 feet in height dominating the town. Soon after leaving Doncaster,

Shaftholm Junction is passed, where the train changes from the metals of the

Great Northern to those of the North Eastern. Then Selby is reached, and the

Ouse is crossed.

York (188 miles from London) is the

first point at which there is a stoppage of any duration, an interval of

twenty minutes for refreshment being given to the day trains. It is one of

the most interesting cities in the kingdom, with its wonderful Minster and

its ancient walls. The walls date from 1280, when they were built by Edward

the First, and the city gates stand now as then, although more than six

centuries have passed over them. The beginning of the glorious Minster was

early in the seventh century, but the

present edifice is said to have

been commenced in 1171.

After leaving York, we pass Thirsk

Junction (210 miles) and Northaflerton Junction (218 miles), the name of the

latter reminding us that there the "Battle of the Standard" was fought in

1138, when the Scots were defeated by the English army under the Archbishop

of York. Crossing the Tees, we enter Darlington (233 miles), "the cradle of

English railways," and a centre of the worsted industry. It was from

Darlington to Stockton, a few miles distant to the north-east, that in 1825

George Stephenson constructed the first railway ever opened for passenger

traffic.

We are now in the great iron and coal

district, but a pleasant change from the industrial character of this part

of the country is afforded by the city of Durham (254 miles), with its noble

cathedral towering on a height that rises from the waters of the Wear. The

architecture is of the Norman period, and the lantern tower, 214 feet in

height, dates from the thirteenth century. The town is also notable for its

fine

Castle, now forming part of the University.

Gateshead (267 miles) is the next

town of importance, lying on the southern bank of the Tyne, facing

Newcastle. Like the latter, it is a centre for collieries, iron works, and

other grimy industrial necessities, and although it is not beautiful, it is

decidedly interesting. The Tyne is crossed by Robert Stephenson's mighty

High Level Bridge (1,337 feet in length and 112 above the water), which cost

nearly half a million to build. Newcastle (268.4 miles) has many claims to

interest—especially the remains of the eleventh-century Castle,—whence the

name is derived, but they are all dwarfed by the importance of the town as a

coaling centre.

Leaving Newcastle behind, the coal

districts are gradually lost to view, and by the time Morpeth (285 miles) is

reached, the scenery is charming again. Soon glimpses of the sea may be had,

and presently Bamborough Castle is seen on a commanding rock, four miles

from the shore, while on a clear day may be detected the Fame Islands, where

Grace Darling performed her heroic rescue. Skirting the cliffs, we reach the

Tweed, the boundary between England and Scotland, which is crossed by a

bridge of twenty-eight arches, 2,160 feet in length and 126 feet above the

water. The opening of this bridge, in 1850, by the Queen, was aptly

described as "the last act of the Union."

Berwick-upon-Tweed (33 miles) is in a

curious position, inasmuch as it is a part of neither England nor Scotland,

but is a separate county and free town to itself. In the olden days the

Scots and the English were continually contending for its possession, and

its sixteenth century ramparts and gates are still in good preservation. At

Berwick-upon-Tweed, where there is a stoppage of a few minutes, the North

Eastern Railway ends and the North British begins. The line continues to

follow the curve of the coast, and skirting Halidon Hill on the left, the

train enters Scotland at Lamberton, at one time an east coast Gretna Green.

Thence the first important point is the ancient town of Dunbar (364 miles),

where Cromwell gained his great victory over the Scottish Army in 1650.

Opposite Dunbar may be seen towering out of the sea to a height of over 400

feet, the Bass Rock, whereon an old State prison used to stand. Following

the Firth of Forth, and looking across to Fife, we pass through Prestonpans,

where Prince Charlie in the '45 defeated Sir John Cope; then comes

Portobello, which serves as a seaside suburb for Edinburgh. Three miles

further and the Scottish capital itself is entered miles from King's Cross),

the sight of Arthur's Seat rising over the city, bringing home to the

traveller the agreeable fact that he has really reached the land of hills.

The short run from Edinburgh to Glasgow, and thence to the Western

Highlands, is described in a subsequent section.

Another route is by the Midland

Railway, via Leeds, Settle and Carlisle, and thence to Edinburgh, Glasgow,

and all places in the North, by the North British.

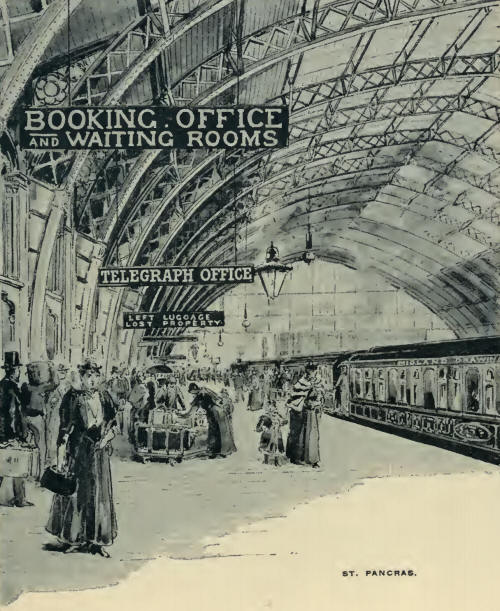

On leaving St. Pancras, a short run

of eighteen miles brings us to the cathedral city of St. Albans, whence the

great Lord Bacon took his title, and where he lies buried. Passing through

Chiltern Green and the "Chiltern Hundreds," so familiar in Parliamentary

life, we reach Bedford (4 miles), with Elstow close by, associated with the

name of John Bunyan. Wellingborough follows, a town with the ruins of

Croyland Abbey near, and presently Kettering (72 miles) is reached, both

towns centres of the Northamptonshire boot and shoe industry. It was in

Kettering that the first missionary meeting was held in England. Leicester

(9 miles), the focus of a great wool-growing country, is the next note

worthy point, an ancient town celebrated for many things, but perhaps most

of all for the introduction of the stocking-frame. Passing through

Loughborough (iii-a miles), Trent (120 miles), and Ilkeston (126 miles), we

come to Chesterfield (146 miles), where attention is riveted by the church

of St. Mary and All Saints on the hillside, with an extraordinary leaning

spire, curiously twisted in a most singular fashion. We are now in the heart

of the Midland coal and iron fields. In the church of the Holy Trinity at

Chesterfield lie the remains of George Stephenson, to whom the neighbourhood

owes so much of its prosperity. At Ilkeston this route is joined by trains

going northwards viii Kettering by way of Melton Mowbray and Nottingham.

Sheffield (158 miles), the renowned

scat of the cutlery and implement trades, is the next town of importance,

and although placed amid beautiful surroundings, it would be difficult to

imagine a more unlovely town, it being wholly devoted to that metal working

which has made the name of Sheffield steel known the world over. To turn the

eye from the mass of smoking chimneys that represents Sheffield, to the

environments of the city is one of the most abrupt contrasts afforded

anywhere in Great Britain. Five rivers converge where Sheffield has been

built, and from their banks rise well- wooded hills, forming a most

picturesque setting for such a "black diamond." Leeds (198 miles), the

centre of the woollen trade, is the next considerable city, and close by, on

the banks of the Aire to the right, a view is obtained of the beautiful

ruins of Kirkstall Abbey. A little further on' we pass through the model

village of Saltaire, built by Sir Titus Salt, the philanthropist and

manufacturer, for the use of his workpeople.

From Settle (236 miles) onwards to

Carlisle the scenery is magnificent, the railway threading for seventy-two

miles a mountainous district presenting almost insurmountable engineering

difficulties in the construction of the road in 1869. Settle itself is a

pleasant little market town surrounded by romantic scenery, some of the most

picturesque scenes in the West Riding being within easy reach. We proceed

onwards through Yorkshire, Westmoreland and Cumberland, piercing the Pennine

range, and winding in and out amongst its numerous spurs, through country so

rugged that the construction of the seventy-two miles of railway involved an

expenditure of over three millions, while seven years were spent in the

task, the principal engineering features being nineteen viaducts and

thirteen tunnels, with innumerable deep cuttings and high embankments.

Proceeding up Ribblesdale, we note on

the right Pen-y-Ghent, a fell 2,273 feet in height, while a few miles

further north rises Ingleborough (2,374 feet) on the left, and on the right

Whernside (2,414 feet). Batty Moss is crossed by a gigantic viaduct, 1,328

feet in length, and 165 feet above its foundations; and Blea Moor is

traversed by a tunnel 2,640 yards in length and 500 feet below the surface.

From the Dent Head viaduct a fine view is obtained of lovely Dentdale on the

left, and, later, Garsdalc is seen on the same side. North of Hawes

Junction, Aisgill Moor is crossed, standing 107 feet above sea level, and

Westmoreland is entered between Wild Boar Fell (2,323 feet) on the left and

Shunnor Fell (2,346 feet) on the right. The way is now along the romantic

Eden Valley, and after passing Appleby (277-41" and leaving behind, on the

right, Cross Fell (2,901 feet), the highest of the Pennine Hills, we reach

Carlisle (308 miles).

Here we are on the borders of

Scotland, and, owing to its situation, Carlisle has seen much of war in the

days when the English and the Scots were two nations. It was besieged by the

Parliamentary Army during the Civil War, and had to surrender, and it is

associated in the memory with the march into England of Prince Charlie in

the '45. Picturesqueness is given to the town by the cathedral and the

castle on the high ground overlooking the River Eden.

If Edinburgh be taken as the starting

point for the Western Highlands, the passenger traverses the land of Scott.

Through Eskdale we go, passing Netherby Hall, the scene of the ballad of

"Young Lochinvar," cross the line of the Cheviot Hills and next the River

Teviot, reaching Hawick 353 miles), an important seat of the Scotch tweed

manufacture. Skirting the Tweed valley, which lies on the right, we pass

close to the ruins of Melrose Abbey. Crossing the Tweed, the Gala Water is

followed to Galashiels, another centre for tweeds and tartans, and presently

Edinburgh is reached-406 miles from London.

|