|

The Corryarick Road, 1.—The

Loch Laggan Road, 2.—Glen Spean, 3.—Loch Laggan, 4.—Anecdote of Cluny

Macpherson, 5.—The Parallel Roads of Glen Roy, 6.—Loch Spey, 7.—Glen Turret,

8.

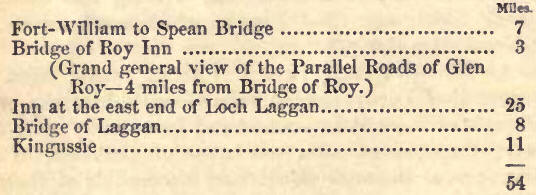

1. The Loch Laggan road forms

a communication between the Great Glen and the central districts of Badenoch,

Strathspey, and Athole; and there is now no connecting line intermediate

between this, at the western, and the great Highland road from Inverness to

Perth, at the eastern extremity of the Great Glen, the Corryarick road, from

Fort-Augustus by Garvamore, having of late years been allowed to fall into

disrepair, and being now impassable for any sort of vehicle, though still

frequented by the droves of sheep and cattle on their way to market. In

commemoration of the Corryarick road—the ne plus ultra of the peculiar

characteristics of the old military highways in the Highlands—we may observe

in passing, that it went right over a lofty mountainous pass, accomplishing

the descent on the southern declivity by no fewer than seventeen traverses,

like the wormings of a cork-screw. Garvamore, a well-known stage on this

road, eighteen miles from Fort-Augustus, and thirteen from Dalwhinnie, now

no more fulfils its oft welcome service of shelter and refreshment to weary

man and beast.

2. In striking contrast with

the Corryarick is the Loch Laggan road—a parliamentary one—admirably

engineered and constructed; it branches off from the Great Glen about seven

miles from Fort-William, at Spean Bridge, a handsome structure across the

river of that name, which issues from Loch Laggan.

From Spean Bridge to Loch

Laggan the distance is seventeen miles, and the length of that lake about

ten. There is now a good inn at the Bridge of Roy, ten miles from

Fort-William, and another at the east end of Loch Laggan (nineteen miles

from Kind ssie), having, instead of a sign, the lintel over the door cut

with the words, "Le Teghearn Cluane," or "The Laird of Cluny," to denote

that the traveller is within his domains, though not now happily subject, as

of old, to his right "of pit and gallows." In the intermediate space of

twenty-five miles, there is no resting-place, except a wretched hovel at the

west end of Loch Laggan.

3. About three miles from the

Bridge of Spean the river Roy falls into the Spean. The valley is here well

cultivated, and boasts of several good farm-houses, as Blairour and

Tirindrish, Dalnapee, Inch, and Keppoch—all perched on the gravel terraces

or platforms which here encircle the glen. The chieftains of Keppoch were

always distinguished for their bravery, and their followers were among the

most hardy of mountaineers. These Macdonalds are by many thought, but

apparently under a misapprehension, to have an equally good title to be

considered the head of the clan as any of the three rival candidates for

that distinction. They held their lands of the clan Chattan, but refused to

acknowledge the right of their superiors, proudly appealing to the claymore

instead of the sheepskin. They are now acknowledged as the head of a small

colony of respectable Roman Catholic families who inhabit this district; and

their mansion contains some relics of the '45, and a few fine pictures

brought from the continent. Glenb rry's Well of the Heads (see page 124)

recounts the murder of the family who occupied the old castle on the river's

bank, of which the site is still shewn. The Duke of Cumberland burnt the

next house, and the present residence is only the third which the family

ever occupied.

For two miles past the Bridge

of Roy the channel of the Spean is remarkably deep, confined, and rocky, and

its waters descend tumultuously; while the road, at a considerable

elevation, passes through a fine oak coppice wood, mingled with birch. On

the hill-face, will be observed, high up, a single level line of the same

character as the Parallel Roads in Glen Roy. The cultivated region

terminates at Tulloch, a substantial farm-house, seven miles distant from

Spean Bridge, and about half way to Loch Laggan. A bleak, ascending, and

mountain-girt moorland succeeds, occasionally, but slightly, enlivened by a

few straggling birches, which retain their place along the banks of the

river; and all along innumerable examples present themselves of the

scratching, polishing, and rounding off of the rocks, especially opposite

the gorge leading to Loch Treig.

4. Loch Laggan is about ten

miles long, and apparently a mile in general breadth, embosomed among

mountains, the declivities of which are, for the most part, covered to the

water's edge with birch, mingled with a large proportion of alder, rowan

tree, aspen, and hazel, the latter peculiarly remarkable from its uncommon

size; all literally grey with age, and fast yielding to the common decay of

nature. On the south side two small islands are seen, with ruins almost

crumbled down to the water's edge. The one is called Castle Fergus, which,

though it may have been occupied by the Lairds of Cluny, has its erection

ascribed to King Fergus, who used this as one of his hunting-seats; but

whether the great Fergus II., the founder of the Scottish monarchy, is more

than problematical. The adjacent isle is said to have been his dog-kennel,

and the height to the south, in front of which the Marquis of Abereorn has

erected a large and beautiful shooting-lodge, is called Ardverakie, or

Fergus' Hill—a name now familiar to the public—inasmuch as her Majesty

the Queen, "on whose empire the sun never sets," sojourned here with Prince

Albert and the Royal Family part of the autumn of 1848.

The Marquis of Abercorn rents these extensive

wilds, including Loch Errocht side, as a deer forest, from Cluny Macpherson.

A small lake intermediate between the loch just mentioned and Loch Laggan,

and which throws into the latter, at its east end, the river Pattoch, is the

true summit level of the country, and thus stands above all the other lakes

which contribute to the waters of the Tay, Spean, and Spey. While standing

on any of the heights hereabouts, the traveller cannot but remark the

evidences of the former submergence of the country under the sea, and also

perceive how distinct the central chains of gneiss and mica schist mountains

are from the group of higher and rougher alps which trend away towards Ben

Nevis and Glencoe. Fine white and blue granular limestone abounds all along

Loch Laggan and the neighbouring ridges, and hence the fertility which is

gradually stealing over the brown wastes.

5. In Glensheira, i1lr. Baillie of Kingussie has

erected a shooting-lodge, and inclosed grounds about it for plantations,

from whence a long line of the old military road from Corryarick may be seen

threading its way for miles along the heath. The adjoining farm-steading of

Shirramore shews what may be done even at this elevation in the way of

gardening, and leaves no excuse to the inn of Dalwhinnie, or any other, even

in the highest situation, for wanting good flowers and vegetables.

While resting at the inn with the Gaelic motto

above quoted, the tourist should visit, close by, the little "Old Kirk of

Laggan," as it is still called. It was the ancient Romish chapel of the

district; and, besides a very small altar-stone, it has two little side

altars, under rounded arches, with a large round granite font at the south

entrance. At the Bridge

of Laggan, about eight miles from the lake, and where there is a small

public-house, the Loch Laggan road crosses the Spey by a handsome framed

timber bridge of 100 feet span, and proceeds along the north side of that

river through the country of the Macphersons, passing the turreted seat of

Cluny, chief of the clan, and joining the Perth and Inverness road near the

Bridge of Spey, about four miles from Kingussie. The ancestor of the present

chief, who figured in the rebellion of 1745, contrived to secrete himself,

after the battle of Culloden, for many years in the immediate neighbourhood

of his own castle. IIc had a small hiding-hole formed, in the salient angle

of a wooded hill, of sticks and turf, with so much art, that the soldiers

stationed in the district, though they suspected he was in concealment very

near them, and of course kept a good look-out, were never able to discover

his place of retreat. lie at length became so adventurous as frequently to

indulge in the pleasures of his family fireside. On one of these occasions

the military got intimation of the old gentleman being unearthed, and a

party were despatched in perfect certainty of securing their prey. Some

friendly messenger, observing their advance to the castle, sped with all

haste to convey the unwelcome intelligence. Unfortunately, poor Cluny was at

the time in a state of insensibility, having indulged over freely in his

glass. What was to be done? The soldiers were close at hand. Wrapping him in

a plaid, his domestics hastily carried him out, and concealed themselves in

the brushwood which skirted the river, till the red-coats, who had just

gained the opposite bank, crossed the ford, and proceeded to the castle,

when they passed in safety. Shortly after, a prattling member of the clan

stumbled by accident through the roof of his chieftain's lower. "What! is

this you, Cluny?" exclaimed the man in astonishment. "I'm glad to see

you."—"But I'm not glad Lb see you, Donald."—"Surely you don't doubt

me?"—"No; but your tongue runs so fast that this story will spread like

wildfire, and by to-morrow morning will be in the mouth of every old woman

in the parish." The clansman vowed secrecy ; but Cluny, knowing his lack of

discretion, and averse to adopt the bloody alternative which self

preservation suggested, lost no time in changing his abode. His fears were

well grounded ; for next day his pursuers duly visited his empty lair.

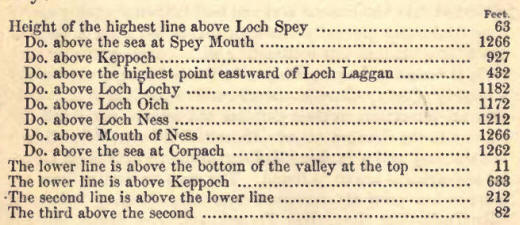

6. The Parallel Roads of Glen Roy.

These remarkable formations have been long known

to the public; but the question regarding their origin has given rise to a

great deal of very violent and ridiculous discussion on the part of those

who, zealous for the greatness and antiquity of their Celtic ancestors, have

maintained them to be the works of the old Fingalians; while from writers of

a different class they have received much patient examination, and have

elicited several important physical observations, and no small degree of

ingenious argument. The theory which one class of observers )could have us

to believe, is, that the roads or terraces in question were formed by human

labour for the purposes of hunting; and, on the supposition that the country

was anciently covered with forests, that they might have served as avenues

for the rapid passages of the huntsmen, and the entrapping or exposure, and

more easy slaughter of the deer.

The roads or lines of Glen Roy are composed of

sand and gravel: they occupy corresponding elevations on the opposite sides

of the glen, and are perfectly horizontal. They are three in number, one

above the other, on each side, or, we should more properly say, all round

the glen. The average breadth of the terraces or lines is sixty feet. Their

course is occasionally interrupted by protruding rocks, or deep chasms; and,

in the centre of the valley, there are one or two detached rocks jutting up

like islands, which have rings, or platforms, round them of a similar

character, and at the same height as the lowest lateral terrace. The surface

is inclined, so that standing on any of them, and looking along, the

horizontal continuity is less observable than when the eye is cast around

the glen, and surveys the whole series at once, when the mathematical

regularity of the lines distinctly marked on the hill face, as a friend

aptly remarked, like the lines of text and half text on a writing school

copy-book, and generally distinguishable by a more decided green, or a

verdant tint contrasting with purple heath or grey rock, is certainly very

striking. As the enduring memorials of a mighty agency, when the waters

covered the face of the earth, they are impressive in their peculiar and

seldom paralleled testimony to the changes on our terrestrial sphere. Glen

Roy is not the only valley in this neighbourhood in which these singular

appearances are to be found. The same or similar lines are more or less

perfectly continued over the adjoining valleys of Glen Turit, Glen Gloy,

Glen Fintack, and Glen Spean, but not approaching in effect to those of Glen

Roy; and, on a more extensive survey, traces of a similar description have

been found in the neighbourhood of Loch Laggan, and in the open country

towards Fort-William. Further observations have likewise fully established

that the interesting phenomena of parallel lines, and alluvial banks,

corresponding in height, though widely separated from each other, are not

confined to this corner of the kingdom; but that similar appearances exist

in other parts of the Highlands, and in the south of Scotland and England:

while in Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and America, they occur on such a

scale as makes their origin quite intelligible. The whole subject has of

late been investigated with extraordinary pains and nicety of observation by

Mr. Robert Chambers of Edinburgh. Previously scientific enquirers had

confined their speculations on the mode of operation of the acknowledged

agent, water, to the theory of a lake, the barrier of which, whether of

rock, gravel, or ice, had given way at successive elevations. It remained

for Mr. Chambers, from a comprehensive survey of similar indications

throughout the kingdom, to adduce the consistent rationale of a general

marine submergence and subsequent elevation, which may now be received as

the correct exposition of these and other similar terraces. lIr. Chambers

and D. Milne, Esq., were the first to observe that the terraces often pass

from one valley to another, along the ridge or water-shed, at the top which

separates them, and that they are prolonged far off into other glens, there

never having been in fact any inclosing barriers.

The following is a note of the measurements made

by Dr. Macculloch of the relative elevations of the lines of Glen Roy:—

The most favourable point of view is that first

attained approaching from the bridge of Roy, being about four miles distant

from the inn. A straight section of the glen, about six miles in extent, is

then under the eye. The road is tolerable, so that the tourist may gratify

his curiosity at little inconvenience; and as the scene is a fine pastoral

valley, the flanking hill sides lofty, steep, and continuous, his

expectations will not be disappointed.

7. Should the pedestrian bend his steps through

the glen, he will find a snug farm house—Glen Roy—about ten miles from the

Bridge of Roy. From this point a walk of about half-a-dozen miles conducts

along the rocky course of a rapidly shelving stream, exhibiting a succession

of cascades, to Loch Spey—the parent source of the river Spey—a bleak

moss-girt sheet of water, imbedded in the central recesses of remote

mountain chains, by shepherds and sportsmen only trod. He will get into the

Corryarick road—near the lodge of the Glensheira shootings, celebrated for

their abundant stock of grouse—two or three miles north from Garvamore, and

about eight or nine miles from the Bridge of Laggan public-house.

8. Or if his object be to regain the Great Glen,

a pretty stiff hill walk of about six miles from the farm-house of Glen Roy,

by a beautifully verdant hollow called Glen Turrit, and across the

intervening hills, will bring him to Laggan, at the east end of Loch Lochy. |