|

Position and General Features

of the Shetland or Zetland Islands, paragraph 1. Climate; Length of the Day

in Summer, 2.—Voyage from Leith, 3.—Fair Isle, 4. Roust of Sumburgh;

Sillocks, or Coalfish, 5.—Dress of the Shetland Fishers, 6. Address and

Language of the People, 7.—Ancient History of Shetland; Harold Harfager's

Conquest; Early Scandinavian Earls of Orkney, 8.—Ancient Measures of Land;

Udal and Scattald, 9.—Ancient Division of the Foudrie of Shetland; Law of

Udal Succession, 10.—First Appearance of Feudalism on the Accession of

Shetland to the Scottish Dominions; the Scottish Earls of Orkney and

Shetland, 11.—Earls Robert and Patrick Stewart; their Illegal and Oppressive

Acts, 12. The Islands pass ultimately to the Morton and Dundas Families,

14—Itinerary: Dunrossness; Quendal; the Cliff Hills; Burgh of Mousa, 14.—Scalloway

Castle; Tingwall,15.—Lerwick, 16.—Bressay Island and Cradle of Noss,17.—Whalsey

and Outskerries, 18.—Fetlar; Unst; Chromat of Iron, Hydrate of Magnesia, and

other minerals, in Unst; Skua Gull, 19.—Yell; Ca'ing Whales; falcons, 20.

The Haaf or Deep Sea Fish, 21.—Fudeland, 22.—Roeness Hill; Villains of Urie,

23.—Papa Stour, 24.—Foula, 25.—Sketch of the Natural History of Shetland;

its Botany, Zoology, and Geology, 26.

"The storm had ceased its

wintry roar,

Hoarse dash the billows of the sea;

But who on Thule's desert shore

Cries, Have I burned my harp for thee?"

MACNIEL.

1. THE group of islands

comprehended under the general name of Shetland, Zetland, Hialtlandia, or

the Thule of the ancient Romans, exceeds a hundred in number; but of these,

only between thirty and forty are inhabited, and they occupy a tract near

the junction of the German and Northern Oceans, extending exclusive of Fair

Isle, between 590 and 60° 50' north latitude, and lying about forty-seven

leagues from Buchanness, on the Aberdeenshire coast, and ninety-six leagues

from Leith; while their longitude is about one degree west of the meridian

of London. [The best authorities the reader can refer to regarding this

group of islands, are Dr. Arthur Edmonstone's "View of the Ancient and

Present State of the Shetland Islands," in two vols. 8vo.; published by

Ballantyne & Co., Edinburgh, in 1809; the recent Parochial Reports in the

New Statistical Account of Scotland, with the general observations on the

county in that work, by Laurence Edmonston, Esq., M. D.; Professor Jameson's

"Mineralogical Travels;" and Dr. Samuel Hibbert's "Description of the

Shetland Islands, comprising an Account of their Geology, Scenery,

Antiquities, and Superstitions, with a Geological map, and numerous plates;"

published by Constable & Co., in one large quarto volume, in the year 1322.]

These islands, although

magnificent and varied in their cliff scenery, are not imposing at a

distance, as their general height above the sea is inconsiderable, the

loftiest hill, that of Roeness, in the parish of North Mavine, only

attaining about 1500 feet of elevation; while the surface of the country is

seldom broken into rough picturesque summits, but disposed in long

undulating heathy ridges, among which are very many pieces of flat swampy

ground, and numerous uninteresting fresh-water lakes. Hence the grandeur and

diversified appearance of the land is not perceived by the stranger, till he

approaches close to the shore; but then, as his bark is hurried on by the

sweeping winds and tides, the projecting bluff headlands and continuous

ranges of rocky precipices begin to develop themselves, as if to forbid his

landing, as well as to defy the further encroachments of the mighty surges

by which they have so long been lashed.

Although, of course,

treeless, and almost shrubless, and, in general, brown and heathy, the

pastures of Zetland nevertheless frequently exhibit broad belts of short

velvety sward, adorned with a profusion of little meadow plants, the more

large and beautiful in their flower-cups, as the size of their stems is

stunted by the boisterous arctic winds. Many very beautiful cultivated spots

occur, especially towards the southern end of the mainland; and the retired

mansions of the clergy and gentry, scattered throughout the islands, are

uniformly encircled with smiling fields, and occasionally with garden

ground.

Besides the connected ranges of precipices, there are everywhere to be seen

immense pyramidal detached rocks, called stacks, rising abruptly out of the

sea, both near and at a great distance from land, the abodes of myriads of

seafowl; and some of them are perforated by magnificent arches of great

magnitude and regularity, while in others there are deep caverns and

subterranean recesses.

Large landlocked bays,

protected from the fury of the ocean by rocky breastworks and islets, afford

numerous sheltered havens to boats and shipping; and the long narrow arms

and inlets of the sea, called ghoes, or roes, which almost penetrate from

side to side of the islands, diversify the surface, and exhibit innumerable

varieties of cliff scenery, and contending tides and currents.

2. Although exceedingly

tempestuous, foggy, and rainy, especially when the wind blows from the south

or west, the climate of Zetland is, from its insular position, on the whole,

milder than its high latitude would otherwise occasion, and the inhabitants

are hence athletic and healthy; but the seasons are so uncertain, the

vicissitudes of temperature so rapid and frequent, and the autumnal gales so

heavy, that but little dependence is to be placed on the grain crops raised

in the islands. The winter, although not characterised by much snow and

frost, is dark and gloomy; but this is counterbalanced and compensated by

the great continued light of the summer months, during which the night is

almost as bright as the day. "The nights," as remarked by Dr. Edmonstone,

"begin to be very short early in May, and from the middle of that month to

the end of July darkness is absolutely unknown. The sun scarcely quits the

horizon, and his short absence is supplied by a bright twilight. Nothing can

surpass the calm serenity of a fine summer night in the Zetland Isles. The

atmosphere is clear and unclouded, and the eye has an uncontrolled and

extensive range; the hills and headlands then look more majestic, and they

have a solemnity superadded to their grandeur; the water in the bays appears

dark, and as smooth as glass ; no living object interrupts the tranquillity

of the scene, but a solitary gull skimming the surface of the sea; and there

is nothing to be heard but the distant murmuring of the waves among the

rocks."

3. The most regular and easy

mode of reaching Zetland is either by a sailing vessel from Leith to Lerwick,

or by the steamer, which, from Aberdeen, carries the mail-bag, and sails, on

an average, once a-week in summer. And if the visitor, upon approaching the

more southerly point of the Zetland coasts, has an opportunity of engaging a

sailing-boat, he will find it by much the best mode of ensuring for himself

a minute and careful examination of the Zetland coasts.

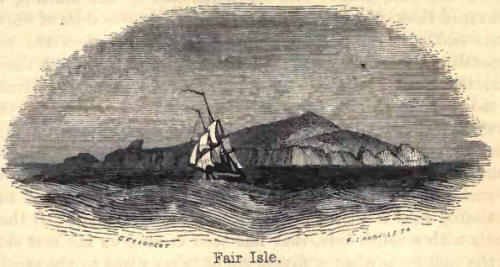

4. We shall suppose,

therefore, that the weather is propitious, and that our tourist has got past

the Pentland Firth and Orkneys, and is leaving FAIR ISLE a few leagues to

the westward of his direct course, ruminating on the unfortunate fate of the

Duke of Medina Sidonia, the admiral of the celebrated invincible Spanish

armada, who, after his defeat in the memorable year 1588, retreated

northward, pursued by the English squadron, and was shipwrecked on. this

bleak inhospitable shore; and whose crew, after great sufferings, were

mostly murdered by the barbarous natives, to prevent a famine in the isle;

the

duke, with a small remnant,

being permitted to escape in a little vessel to Quendal, on the mainland of

Shetland, where they were kindly entertained, and ultimately assisted in

their return through France to the fertile valleys of Old Spain.

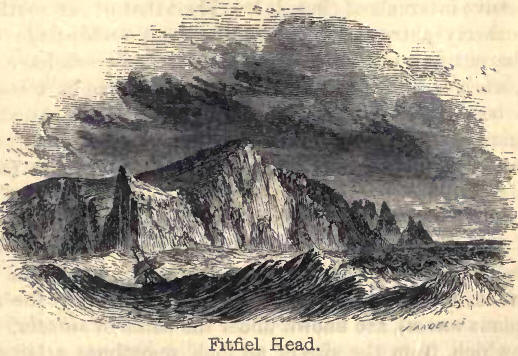

No sooner do the rocks of

Fair Isle recede from observation, than FITFIEL HEAD (the white mountain), a

considerable hill

in the south of the mainland

of Zetland, first rises to view; and a contiguous one, to the east of it,

less elevated, named SUMBURGH HEAD; the general features of the bleak low

hills of the district of Dunrossness also soon thereafter multiplying on our

sight.

5. But, before reaching land,

our vessel must have a rocking in the Roust of Sumburgh, the Scandinavian

term applied to a strong tumultuous current, occasioned by the meeting of

the rapid tides, which here join from the opposite sides of Shetland, and

rush towards the Fair Isle. Even when the sea generally is calm, and when

viewed from the adjoining headland, there is in the Roust the appearance of

a turbulent stream of tide, about two or three miles broad, in the midst of

the smooth water, extending a short distance from Sumburgh, and then

gradually dwindling away, so as to terminate in a long slender dark line,

bearing towards Fair Isle. At the beginning of each daily flood, the tide in

the Roust is directed to the eastward, until it passes the promontory of

Sumburgh: it then meets with a south tide, that has been flowing on the east

side of the country; when a divergement takes place to the southeast, and

lastly to the south. At high water there is a short cessation of the tide,

called the STILL: the ebb now begins, first setting north-west, and then

north, until the commencement of the flood. The various directions of the

tides of Zetland are no doubt owing, in a considerable degree, to

modifications which take place from the number and form of the various

headlands and inlets of the coast; but, since they are propagated at

successive intervals of time, it is evident that at the northerly and

southerly extremities of the Shetland archipelago they would be naturally

opposed to each other. Vessels have been known, when falling into the Roust

in a calm, to be tossed to and fro between Fitfiel Head and Sumburgh Head, a

distance of no more than three miles, for five days together; and, while the

sea here is always heavy, in a storm the waves rise mountains high.

In the Roust of Sumburgh

there is a considerable fishery for the Gadus carbonarius, or coal-fish,

called here the seethe, elsewhere the cuddie; and their young, which enter

the bays in myriads (while the full-grown fish sport among the most

tumultuous waves), are known under the name of sillocks. The seethe, which,

from the size of an inch, sometimes attains the length of three feet, is

caught by hand-lines, baited with haddock or shell-fish; and our proximity

to land is announced, in good weather, by the appearance of numerous boats

fishing for them and for cod.

Although the fry of the

coal-fish, in general, frequent retired bays, yet their favourite resort is

often among the constant floods and eddies near sunken rocks and bars that

are alternately covered and laid bare by the waves, and the smaller fry

appear to covet the security of thick plantations of sea-ware, within the

shelter of which they are screened from the keen look-out of their natural

enemies of the feathered race. As remarked by Dr. Hibbert, "There is,

probably, no sight more impressive to the stranger who first visits the

shores of Zetland than to observe, on a serene day, when the waters are

perfectly transparent and undisturbed, the multitudes of busy shoals, wholly

consisting of the fry of the coal-fish, that nature's full and unsparing

hand has directed to every harbour and inlet.

"As the evening advances,

innumerable boats are launched, crowding the surface of the bays, and filled

with hardy natives of all ages. The fisherman is seated in his light skiff,

with an angling rod or line in his hand, and a supply of boiled limpets near

him, intended for bait. A few of these are carefully stored in his mouth for

immediate use. The baited line is thrown into the water, and a fish is

almost instantaneously brought up. The finny captive is then secured, and

while one hand is devoted to wielding the rod, another is used for carrying

the hook to the mouth, where a fresh bait is ready for it, in the

application of which the fingers are assisted by the lips. The alluring

temptation of an artificial fly often supersedes the use of the limpet; and

so easily are captures of the small fry made, that young boys, or feeble old

men, are left to this business, which not unfrequently is carried on from

the brink of a rock, while the more robust natives are engaged in the

deep-sea fishery, or the navigation of the Greenland seas."

The Scandinavian character of

the natives first becomes evident in the form and lightness of their boats

or yawls, the planks of which are still imported from Norway, so modelled by

the hands of the carpenter, that, when they arrive in Shetland, little more

labour is required than to put them together. These boats are generally

about eighteen feet in keel, and six feet in beam ; they carry six oars, and

are furnished with a square sail. Their extreme buoyancy, and the ease with

which they cut the waves, are the circumstances insisted on by the

fishermen, as rendering their construction particularly adapted to the.

stormy seas. upon which they are launched.

6. "The boat dress of the

fisherman is, in many respects, striking and picturesque. A worsted covering

for the head, similar in form to the common English or Scotch nightcap, is

dyed with so many colours, that its bold tints are recognised at a

considerable distance, like the stripes of a signal flag. The boatmen are

also invested, as with a coat of mail, by a surtout of tanned sheepskin,

which covers their arms, and descends from below their chin to their knees,

while, like an apron or kilt, it overlaps their woollen fenwralia: for, with

the latter article, it is needless to observe, the Shetlander is better

provided than the Gaelic Highlander. The sheepskin garb has generally an

exquisite finish given to it by boots of neatskin materials, not sparing in

width, reaching up to the knees, and altogether vieing in their ample

dimensions with the notable leather galligaskins with which painters have

long been wont to encompass the royal calves of Charles XII. when they have

represented him as planning the trenches of Fredericshal. There can be no

doubt that this leathern dress is of Scandinavian origin; a similar one is

still worn in the Faroe Isles, and Bishop Pontoppidan describes the same as

being common in his time among the peasantry of Norway. This ponderous and

warm coriaceous garb is, however, sometimes disdained by the younger and

more hardy natives, who content themselves with a common sea-jacket and

trowsers of the usual form, and, in place of the worsted cap, with a plain

hat of straw."

7. Should the tourist,

desirous of exploring the country right before him, take leave of his vessel

at the nearest point of Dunrossness, which is about thirty miles south of

Lerwick, he will probably be struck with the high sharp accent and rapid

utterance of the first person who accosts him, the prevailing manner of

speech of the Shetlanders resembling much more that of the inhabitants of

England than of Scotland, and having also none of the slow drawl of the

Highlander, but much of the modulated and impassioned tones of the Irish.

The first question likely to be put to the stranger, preceding even the

usual interrogatories of name, country, occupation, destination, and so

forth, will be about the price of oatmeal in Leith, with which it is of

course expected that he should be as much interested as the natives

themselves. This is very natural ; the precariousness of their crops, from

the uncertainty of the climate, rendering these poor islanders very

dependant on foreign supplies for the luxury of meal, which is often too

scarce to be used as a necessary article of daily consumption.

8. The history of few

secluded communities can, in some respects be more fraught with interest

than that of the inhabitants of Zetland; although the picture, especially in

its central parts, is almost exclusively a melancholy one, exhibiting the

patient endurance, by a generous people, of very many grievances, at the

hands, not of their own ancient Norwegian udal landlords, but of tyrannical

strangers intruding on them as feudal superiors, after their connexion with

the crown of Scotland ; and these foreigners themselves being often but

temporary possessors, renting the islands from their sovereigns for a mere

trifle, and endeavouring to repair their finances, for the most part

desperate, by grinding down the poor.

From the slight notices in

the ancient classics, and from more recent authentic records, it has been

rendered probable by Dr. Hibbert that the successive early colonists of

Orkney were composed of Celtic, Saxon, and Scandinavian tribes, but that the

first sect never reached Zetland, in no part of which are Celtic names of

places to be found. The general result of this very learned author's

researches has thus enabled him to keep in view three great periods in the

history of these islands. "In the first period, when Agricola visited

Orkney, a Celtic race very probably inhabited the country, who appear to

have completely forsaken it a century and a half afterwards, since it was

described by Solinus, in the middle of the third century, as a complete

desert. In the second period, Orkney, and probably Shetland also, were

infested by a Gothic tribe of Saxon rovers, who were routed, A. D. 368, by

Theodosius. In- the third period, probably at or before the sixth century,

succeeded in the possession of these islands, the Scandinavians, who were

the progenitors of the present race of inhabitants in Orkney and Shetland."

HAROLD HARFAGER, or the

FAIR-HAIRED, having, as Norwegian poets narrate, to please his love, the

Princess Gida, reduced all Norway under his power, in the year 875, was

roused to avenge the devastations and slaughter committed on the coasts of

his kingdom, by the numerous pirates and petty princes who had escaped from

their native land, impatient of his yoke, and who had settled themselves in

Iceland, Faroe, Shetland, and Orkney. He soon freed the seas from these

hordes, and subjugated all the islands adjoining the north of Scotland,

including the Hebrides. Harold then offered the conquered provinces of

Caithness, Orkney, and Shetland as one earldom, to a favourite warrior,

Ronald, Count of Merca; but this nobleman, being more attached to a

Norwegian residence, resigned the grant in favour of his brother Sigurd, who

was accordingly elected the first Earl of Orkney, and from whom sprang the

true Scandinavian dynasty of the Earls of Orkney and Shetland, the latter

country being at first too insignificant to be included in the title,

although it was comprehended in the grant. The earldom was unfettered by any

homage to a superior; and Sigurd, the first earl, by an alliance with

Thorfin, son of the King of Dublin, soon greatly extended his dominions by

the conquest of Caithness, Sutherland, and part of Ross and Moray shires.

9. But both for the support

of the new earl, and that the islands and coasts which he had subdued might

no longer be a refuge to his foes, Harold Harfager peopled them by

individuals firm in their attachment to the crown of Norway; and, in a

partition of the vanquished territories among the first colonists, the

magnitude of shares would of course be regulated by military or civil rank

and services. "But in measuring out allotments in proportional shares," says

Dr. Hibbert, "it would be necessary to resort to some familiar standard of

valuation. The Norwegians, in the time of Harold, appear to have scarcely

known any other than what was suggested by the coarse woollen attire of the

country named wadmel: eight pieces of this description of cloth, each

measuring six ells, constituted a mark; the extent, therefore, of each

Shetland site of land bearing the appellation of MARK was originally

determined by this rude standard of comparison, its exact limits being

described by loose stones or shells, under the name of mark-stones, or

meithes, many of which still remain undisturbed on the brown heaths of the

country. The Shetland mark of land presents every variety of magnitude,

indicating at the same time that allotments of land were rendered uniform in

value by a much greater extent of surface being given to the delineation of

a mark of indifferent land than to soil of a good quality." Subsequently, on

the introduction of metals as a standard for value, the mark of land was

seldom thought of in reference to the wadmel or cloth, but the equivalent

for it, or the mark-weight of, metal, was divided into eight parts, called

eures, or ounces, like those of the mark of wadmel, and hence we find such

subdivisions of the ground as eurelands or ouncelands.

Before the reign of Harold,

Scandinavian lands had been held unfettered by any tax or impost. The hardy

Northman, after discovering that a soil could be so improved by labour as to

afford to the cultivator a subsistence less precarious than that which

depends upon the resources of fishing or hunting, could enclose a piece of

ground around the cabin he had erected, to which he would affix some limited

notions of property; and such enclosed land, though it had only a single

cottage on it, was originally called a TOWN, the idea that this name

includes a collection of buildings being a change of signification induced

by feudal maxims and habits. Harold is supposed to have been the first

monarch of Norway who oppressed his people by levying a tax or scat upon

land. "But in whatever mode the tax might have been exacted in Norway, it

appears that in the colony of Shetland, the enclosures designed for

cultivation were ever considered as property that was sacred to the free use

of the possessor: these were never violated by the intrusion of a collector

of scat. Each mark of land bounded by mark--stones, or meithes, naturally

contained very little soil fit for tillage. It was, therefore, from

pastures, and from the produce of the flocks which grazed upon them, that

the scat or contribution for the exigencies of the state of Norway was

originally levied. The patch of ground which the possessor had enclosed

being rendered exempt from every imposition to which grazing lands were

liable, it is possible that the uncontrolled enjoyment of the soil destined

for culture first suggested to the early colonists of Shetland, such a term

as ODHAL, or UDAL, expressive, in the northern language, of free property or

possession; whilst to pasture land, which was held by the payment of a scat

or tax, the distinctive appellation was awarded of SCATTALD. Thus the

Shetland mark of land originally included pasture or scattald, as well as

enclosed cultivated ground, free from scat, and hence named udal.

Accordingly, when a mark of land was transferred by sale or bequest from one

individual to another, or was even let to a tenant, the proportion of

scattald remaining after the patch of free arable ground had been separated

from it, was always clearly expressed."

10. Shetland, being by nature

a separate province from the other divisions of territory belonging to the

earldom of Orkney, had a separate civil governor appointed by the King of

Denmark, as judge of all civil affairs; the country at the same time

acquiring the name of a Foudrie, and being subdivided into several

districts, each of which was under the direction of an inferior foude, or

magistrate, whose power extended little beyond the preservation of the peace

and good neighbourhood. The lesser foude was assisted in the execution of

his office by ten or twelve active officers, called rancilmen, and by a

lawrightman, who was entrusted with the regulation of weights and measures.

Cases of importance were, at stated periods, tried by the GRAND FOUDE; and

at an annual court—at which all the native proprietors or udallers were

obliged to attend—new legislative measures were enacted, appeals were heard

against the decisions of the subordinate foudes; and causes involving the

life or death of an accused person were determined by the voice of the

people. Such is an outline of the free and simple polity of the ancient

Shetlanders, and which partook so little of feudalism, that the Earl of

Orkney was regarded as possessing no legal civil authority whatever, nor any

way entitled to interfere with the national laws, rights, and privileges of

the udallers. He was only the military protector of the islands, who, on an

invasion of the coasts, or when any foreign enterprise was contemplated, had

merely to unfurl the Black Banner of the Raven, to ensure the repairing of a

crowd of eager warriors to his standard. The extensive possessions and

wealth of the Earl no doubt secured him power, and often control, over the

national councils, but such influence was ever considered as illegal. Even

when soldiers were required to be raised, a popular convocation was held,

when the levy was made up, by their fixing the number of men which each

village or town could conveniently furnish.

Our limits prevent our

following up the details of the law of the udal succession to lands which

prevailed in Shetland while it remained under the crown of Norway, all the

features of which differ remarkably from the feudal maxims which regulated

the transmission of property in Scotland.

Northern antiquaries have

bestowed much attention on this interesting topic, and it has been most

completely and successfully elucidated by Dr. Hibbert in his admirable work

on Shetland, and in several papers in the Transactions of the Society of

Scottish .Antiquaries, to which we must refer our readers. We may shortly

remark, however, that, by this law, which is ascribed to King Olaus, the

arable ground, which, having been separated by enclosure from the scattald,

was the free property of the cultivator, went to all the children of the

proprietor, male and female, in equal shares; and, in order to obviate any

evasion of this rule of inheritance, no one could dispose of an estate

without the public consent of his heirs. Even the property of the Earls of

Orkney was often portioned out in nearly equal shares among descendants, and

the kingdom of Harold Harfager himself was divided among male successors in

nearly equal proportions.

11. On the accession of the

Zetland Islands to the Scottish crown, these principles of law were

gradually encroached upon, and most of the grievances of the people, for

centuries afterwards, were founded on the barbarous and oppressive

endeavours of the Scottish earls to introduce feudal subjection and

seigniorage, in place of the ancient udal tenures. Our article on Orkney

contains a Sketch of the farther encroachments of the Scottish monarchs, and

their minions, on the liberties of these poor islanders, to which we refer.

12. The transition from the

freedom enjoyed by the islanders under their native sovereigns and earls, to

the feudal thraldom imposed by the Scottish government, was consummated in

the reign of Queen Mary, who, in the year 1565, made an hereditary grant of

the crown's patrimony, and of the superiority over the free tenants in the

islands, to her natural brother, LORD ROBERT STEWART, THE ABBOT OF HOLYROOD,

for an annual acknowledgment of £2006: 13: 4 Scots. With her usual caprice,

this grant was afterwards revoked by Mary, for the purpose of erecting

Orkney and Shetland into a dukedom for her favourite the Earl of Bothwell;

but on his attainder, Lord Robert was immediately reinstated in the

enjoyment of the crown lands, when he left to a superintendent the

collection of the third of the popish benefices appointed by the reformed

parliament of Scotland to be collected for the support of parochial

ministers, and contented himself with the immense temporal influence which

the estates of the crown and of the bishopric gave him, when subsisting

under one undivided fee. An attempt was now made to bring the free tenants

of the crown under his power as a mesne lord, and, by issuing out new

investitures to them, Lord Robert materially increased his revenue. "But the

chief design of this tyrant," as stated by Dr. Hibbert, "was to wrest, by

oppression and forfeiture, the udal lands from the hands of their possessors

; to retain the poor natives who might be forced out of their tenements as

vassals on his estates; and to entail upon them the feudal miseries of

villain services. This he was enabled to accomplish by establishing a

military government throughout the islands, which was intended to impede all

avenues to judicial redress. his rapacity and oppression at length became so

great, and the complaints of the natives so loud, that the Scottish

government was obliged to interfere ; and, after an investigation, Lord

Robert was condemned to imprisonment in the Palace of Linlithgow, and the

estates of Orkney and Shetland reverted, by his forfeiture, to the crown.

lie was thus, for three years, restrained from tyrannising over the

islanders ; but his interest at the Scottish court, where his crimes and

follies were always forgiven, procured for him, in the year 1581, a

reinstatement in his former possessions ; and, to enable him to control the

decrees of justice in the country courts with less chance of detection, he

had the address to procure for himself the heritable appointment (by King

James VI., in 1581) of JUSTICIAR, with power to convoke and adjourn the

law-tings, to administer justice in his own person, and appoint the various

officers of the court ; to all which were added the hereditary titles of

Earl of Orkney and Lord of Zetland. One of the most successful measures of

Earl Robert for increasing his exactions from the poor Shetlanders was his

afterwards effecting, by quibbling, and a technical interpretation of his

new charters, the setting aside of the ancient shynd-bill or document by

which land was conveyed to a purchaser. It was the recorded decree of a

court, that all the heirs and claimants over a property consented to its

transfer or sale; and when signed and sealed by the foude, it constituted

the only legal title by which udal lands could be bequeathed to heirs, or

disposed of by sale. The abolition of this excellent form must have greatly

increased the dependence of the people on their feudal lord ; and the new

mode of investiture introduced by him, with all the burdens and casualties

common in Scotland, must have materially augmented his revenues.

EARL ROBERT STEWART was

succeeded, about the year 1595, by his son, Earl Patrick, a man more wicked

and rapacious than his father; and who, at the time of his investiture, had

wasted his original patrimony by riotous expenses, which he sought to redeem

by fraud and violence. He compelled the poorest of the people by force to

erect his Castle of Scalloway; and many wealthy Scandinavians were obliged

to abandon their possessions and quit the country. At length the

lamentations of the inhabitants pierced even the dull ears of the Scottish

government, and Earl Patrick was summoned, by open proclamation, "to compear

upon the 2d of March 1608, to answer to the complaints of the distressit

people of Orkney." The charges were fully proved, principally by the humane

bishop of the province, who had matured and preferred them; and, the earl

being cast into ward, and afterwards beheaded, the government of Orkney and

Shetland was for a time intrusted to Bishop Law. In the year 1612, the lands

and earldom were annexed to the crown, and erected into a STEWARTRY; and Sir

James Stewart got a grant of the islands in the quality of farmer-general. A

court of stewartry was erected, the power of the bishop was restricted to

the exercise of his jurisdiction as commissary; and causes were now tried in

the halls of the Castles of Scalloway and Kirkwall ; while the open spaces

of the Scandinavian law-tings were again devoted to legislative

convocations, at which a little parliament of udallers again began to meet,

in order to replace, by a fresh code of pandects, the ancient law books

which Earl Patrick had destroyed.

But the sufferings of the

people had not yet come to an end. The tyrannical privilege first assumed by

the late Earls of Orkney, of condemning lands on pretended feudal

forfeitures, was perpetuated in various ways by the tacksmen of the crown

revenues. The oppressions of Sir James Stewart, the new farmer, occasioned,

in ten years afterwards, his recall. The crown estates were then let out to

a number of court favourites, who felt little compunction in flagrantly

abusing their trust; and the udallers were reduced, by their overwhelming

authority, to the most dispirited state of humiliation.

In 1641, the rents of the

bishopric, upon the establishment of a presbytery in the islands, were

granted to the city of Edinburgh; and, two years afterwards, King Charles

I., on the fictitious plea of a loan affirmed to have been made to him by

the Earl of Morton, procured from parliament the confirmation of a grant, to

his favourite, of the lands of the Earldom of Orkney and lordship of

Shetland, subject to redemption by payment of £30,000 sterling. Soon after

this contract the Earl of Morton died, and his son, on coming into

possession of the islands, immediately endeavoured to sweep away every relic

of the udal tenures, and especially of the shynd-bill, which he represented

as an illegal infringement of his universal right of superiority over the

lands of the province.

13. During the Commonwealth,

Cromwell sent deputies into the islands, who committed great irregularities,

particularly in the clandestine alteration of the weights and measures.

Charles II. restored episcopacy, and commanded the rents of the church lands

to be paid to the bishop. As the family of Morton was then in embarrassed

circumstances, the possession of the crown lands was committed in trust for

the family to GEORGE VISCOUNT GRANDISON, who appointed ALEXANDER DOUGLAS OF

SPYNIE as factor to receive the crown rents of the islands, and to grant feu

charters. Spynie's mission to Shetland is well remembered ; for he was

instructed to dispute the validity of all tenures which did not depend on

confirmations from the crown; and as many of the recent settlers possessed

only dispositions and sasines from the old udallers, which they expected

would have been at least preferable to the despised .shynd-bill, they were

likewise compelled to make up new titles as vassals to the king. From this

period, then, may be dated the complete subversion of the ancient laws of

the country. The udallers now abandoned for ever the open space of the

lawting, where, beneath no other canopy than the sky, their fathers had met

to legislate for at least six centuries. They were henceforward required, as

vassals of the crown, to give suit and presence at the courts held within

some covered hall at Kirkwall and Scalloway.

The right of representation

in parliament, bestowed on the people of Orkney,—for, till the late Reform

Act, those of Shetland were denied the privilege of sharing in the election

of a member of the British senate, and which right was necessarily exercised

under the Scottish law regulating freehold qualifications,—likewise entailed

on the former, in the most complete manner, all the forms of feudal

conveyancings, and thus caused

them farther to seek an

alteration of the usages of their forefathers.

In the reign of Queen Anne,

the Morton family acquired still larger and less qualified grants of the

islands, and especially their vice-admiralty, and the right of patronage to

all the churches ; and, in 1742, the Earl of Morton obtained from parliament

a discharge of the claim of reversion previously competent to the crown:

but, in the year 1776, the earl found this property so troublesome to him,

from the vexatious lawsuits in which it had involved him, that he sold his

entire rights over Orkney and Shetland for the sum of £60,000 to Sir

Lawrence Dundas. The Earl of Zetland, whose father, Lord Dundas (lately

deceased), obtained this title, is now lord-lieutenant of the Stewartry. The

islands pay their proportion of the land-tax, and in every other respect

have become subject to British laws, their internal administration being

committed to the sheriffs and justices of peace.

14. The preceding historical

details have been rendered necessary by our desire to make tourists fully

acquainted with the associations of the people among whom they have to

sojourn, before mixing with them, and to avoid repetition and lengthened

explanations in the subsequent parts of our Itinerary. Landing, then, on the

mainland, and securing one of the first of the little black or brownish

barrel-bellied broad-backed ponies he meets with, we would advise the

tourist, after taking a peep of the fine corn lands about Dunrossness and

Quendal, to hasten on over the bleak mountain ridge of the Cliff Hills,

which are too often muffled up in wet and exhaled mists, to Lerwick,

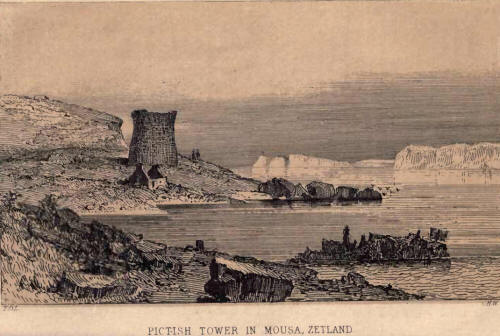

visiting on his way the Scandinavian burgh of Mousa,

[The Burgh of Mousa is,

perhaps, the most perfect Teutonic fortress now extant in Europe. It

occupies a circular site of ground, shout 50 feet in diameter, and is built

of middle-sized schistoze stones, well laid together without any cement. The

round edifice attains the height of 4-2 feet, bulging out below and tapering

off towards the top, where it is again cast out front its lesser diameter,

so as to prevent its being scaled from without. The doorway is so low and

narrow as only to admit one person at a time, and who has to creep along a

passage 15 feet deep ere he attains the interior open area. lie then

perceives that the structure is hollow, consisting of two walls, each about

five feet thick, with a passage or winding staircase between them of similar

size, and enclosing within an open court about 20 Feet in diameter. Near the

top of the building, and opposite the entrance, three or four vertical rows

of holes are seen, resembling the holes of a pigeon-house, and varying from

eight to eighteen in number. These admitted air and a feeble degree of light

to the chambers or galleries within, which wound round the building, and to

which the passage from the entrance conducts, the roof of one chamber being

the floor of that above it. In this structure, it is on record that the

ancient inhabitants, on the occasion of sudden invasion, hastily secured

their women and children and goods; and it would appear that even one of the

Earls of Orkney was not able to force it. Such burghs seldom yielded except

to stratagem or famine; and being the places of defence round which the huts

of the neighbourhood naturally arranged themselves, their nanie came

latterly to designate the town or burgh which arose about them.]

and the modern Castle of

Scalloway. For several miles before him, as he scampers on, the traveller

will perceive the sea-coast broken into creeks, islets, and sea holms, and

long lines of ragged rocks; and around him, misty hills and heaths without a

shrub, but relieved occasionally by groups of cottages, and winding stone

dykes, intended to protect from the invasions of cattle a few patches of

greenish corn land.

15. Scalloway Bay, with the

numerous cottages, of a better description than common, arranged round its

fine semicircular harbour, is exceedingly picturesque. Towering above the

village is the castellated mansion of Earl Patrick, erected in the year

1600, with the building of which a most flagrant exercise of oppression is

still remembered by the poor Shetlanders. Under the penalty of the

forfeiture of property, a tax was wantonly laid by the Earl on each parish,

obliging the inhabitants to find as many men as were requisite, as well as

provisions for the workmen, who were kept to their tasks by military force.

The castle is a square formal structure, now reduced to a mere shell,

composed of freestone brought from Orkney, and of the fashion of most of the

castellated mansions of the same date in Scotland; it is three storeys high,

the windows being of a very ample size, with a small handsome round turret

at the top of each angle of the building. Entering by an insignificant

doorway, over which are the remains of a Latin inscription, we pass by an

excellent kitchen and vaulted cellars, while a broad flight of steps leads

above to a spacious hall ; the other chambers, however, being of a small

size.

North from Scalloway the

tourist should visit the beautiful green valley of Tingwall, contained

between the Cliff Hills on the east, and a less steep parallel ridge on the

west. He will first meet a large stone of memorial, and in a small holm at

the top of the adjoining loch he will be shewn the seat where the chief

foude, or magistrate, of Shetland was wont to issue out his decrees—a

communication having been made to it from the shore by means of large

stepping-stones. The foude, his raadmen or counsellors, the recorder,

witnesses, and other members of the court, occupied the inner area of the

holm, their faces being turned towards the east, while the people stood on

the outside of the sacred ring and along the shores of the loch. When, in

criminal cases, the accused was condemned by this court, he had the right of

appeal to the people at large; and if they opened a way for him to escape

from the holm, and he was enabled, without being apprehended, to touch the

round steeple of the adjoining ancient church of Tingwall, the sentence of

death was revoked, and the condemned obtained an indemnity.

16. A paved road, cut across

a thick bed of peat moss, leads from the fertile vale of Tingwall to Lerwick,

distant about four miles; and, as the traveller approaches the town, he will

likely be regaled with a splendid view of the Sound of Bressay, burdened

with vessels of all sizes, among which stately king's ships may be

majestically gliding, and backed by the fine symmetrical conoidal hill which

occupies the whole of the island of Bressay, and by the distant cliffs of

Noss. Ranged along the shore are a number of white houses, of from two to

three storeys in height, roofed with a blue rough sandstone slate, but

disposed with the utmost irregularity, and an utter disregard of every

convenience, except that of being as near as possible to the sea and its

landing-places. Such is Lerwick, the capital of Shetland, which seems to

have been originally erected in the beginning of the seventeenth century, in

connexion with the Dutch fishermen, whose busses, to the number of not less

than 2000, annually crowded on the approach of the fishing season into

Bressay Sound. Nor were the subsequent attempts of builders to form a street

or double row of houses more successful in introducing ideas of mutual

accommodation, in order to obtain equality of breadth and straightness of

direction. The sturdy Shetlander was not to be so dispossessed of his

ground; and, accordingly, some taller houses may be seen to advance proudly

into the road, taking precedence of the contiguous range, while in some

places lesser dwellings claim the privilege of encroachment, as of equal

importance. The salient and re-entering angles of fortification may thus be

studied in Lerwick; or, in the more peaceful thoughts of Gray's description

of Kendal, we may say—"They seem as if they had been dancing a country

dance, and were out. There they stand, back to back, corner to corner, some

up hill, some down." Like part of Stromness in Orkney, the Lerwick street is

laid with flags, which are seldom pressed by. heavier beasts of burden than

the little shelties from the neighbouring scatholds, loaded with cazies of

turf ; and no cart ever rattles over their surface. The number of shops in

the town, and the groups of sailors of all nations engaged in their small

purchases, gives it an unusually lively appearance. It boasts no kind of

manufactory except one for straw-plait, and Shetland hose and other woollen

stuffs, which are daily becoming more and more valuable, and no public

buildings except one, which serves as a town-house, court of justice,

masonic lodge, and prison, to which may be added the parish kirk, and

dissenting meetinghouse. Provisions are here abundant, and about one-half

their price in Scotland; and the great boast of the inhabitants of Lerwick

is its vegetables, and especially its esculent roots and artichokes. The

number of inhabitants is greatly increasing: by the census of 1821, the

parish contained 2224 individuals; and by the census of 1841, 3284. In 1701,

when the adjoining Sound was frequented by Dutch vessels, from 200 to 300

families resided in Lerwick; but, in 1778, Mr. Low remarked that the town

then only contained 140 families. The printed reports of the Government

census of 1841, state the gross population of the Orkney and Shetland Isles

to be together 60,007, without discriminating between the two groups; and

the increase to be three per cent, within the previous ten years. Dr. L.

Edmonston, writing in 1840 for the New Statistical Account, believed the

population to be decreasing, owing to the disasters of the recent seasons,

and the departure from the country of the young and able-bodied men. The

proportion of females to males he reckons to be as two to one; but he thinks

that, under judicious management, the Shetland Isles could probably maintain

three times the present number of inhabitants, which a few years ago, he

states, amounted to 31,000.

To the south of the town

stands the citadel, named after the queen-consort of George III.,

Fort-Charlotte. It is believed to have been originally constructed during

Oliver Cromwell's time, and rebuilt by Charles II. in 1665; but, being burnt

and rendered defenceless in the year 1673 by a Dutch frigate, it was utterly

neglected, till remodelled in 1781, and mounted with twelve guns, for the

protection of the town from attacks by sea.

The habits of the higher

classes in Lerwick differ but little from those of the generality of

Scottish towns. Like the more wealthy inhabitants of the adjoining country

and of Orkney, they receive part of their education in Aberdeen or

Edinburgh, or in England; returning with much-to-be-admired contentment to

their native solitudes, to which they are uniformly observed to have the

strongest attachment. Strangers have always spoken in the highest terms of

the urbanity of the people of Lerwick, and sailors are wont to descant with

rapture on the hours they have spent in its hospitable harbour. When Dr.

Hibbert visited Lerwick, there was but one inn in the place, where be met

with much civility and attention.

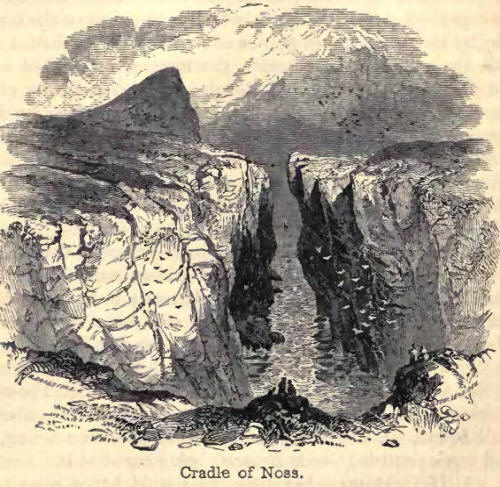

17. From Lerwick the tourist

should cross over to Bressay, and thence to the island of Noss, to see the

famous wooden trough or cradle, suspended by ropes, communicating with the

Holm of Noss. It is sufficient for the conveyance across of one man and a

sheep at a time. The Holm, which is only 500 feet

in length and 170 broad,

rises abruptly from the sea in the form of a perpendicular cliff, 160 feet

in height, the elevation at which the cradle hangs over the boiling surge in

the channel below. The temptation of getting access to the numberless eggs

and young of the sea-fowl which whiten the surface of the Holm, joined to

the promised reward of a cow, induced a hardy and adventurous fowler, about

two centuries ago, to scale the cliff of the Holm, and establish a connexion

by ropes with the neighbouring main island. Having driven two stakes into

the rock, and fastened his ropes, the desperate man was entreated to avail

himself of the communication thus established in returning across the gulf;

but this he refused to do, and, in attempting to descend the way he had

climbed, he fell, and perished by his fool-hardiness. We will not spoil the

interest the tourist will feel in ascertaining on the spot the method

whereby the communication was afterwards completed, and the cradle lowered

down on its cordage for the transport of the little stock of sheep which now

tenant the Holm, by describing the process.

Proceeding northward along

the coast of the mainland to the capacious Bay of Cat Firth, which is closed

in on the farther side by the promontory of Eswick, the traveller should

next visit the valley of Burgh, with the remains of the old house and chapel

of the Barons of Burgh—a Scottish family of the name of Sinclair, who were

established here in 1587 by King James VI., on the express condition that

they should not hold their lands according to the law of udal succession,

but by feudal tenure, as observed in Scotland; and which family, during the

seventeenth century, maintained here an establishment of a degree of

splendour previously unknown in Shetland.

Passing on to the house of

Nesting—which is noted as the spot where the Parson of Orphir in Orkney, a

creature of Earl Patrick Stewart, who had ministered greatly to his avarice,

was pursued by four brothers, who here slew him, and of one of whom it is

recorded, that, tearing open the dying man's breast, he drank of his heart's

blood—we reach the barren shores of Vidlin Voe, and the house of Lunna, from

the neighbourhood of which a long promontory stretches out for several miles

into Yell Sound. Lunna is a great fishing station—much ling, cod, and torsk

or tusk (Gadus Brosme) being cured at it.

18. If the tourist has time,

he should hence cross to the island of Whalsey, in which he will see a

system of farming practised that would not do discredit to the Lothians, and

the appearance of which is highly encouraging to every philanthropic mind;

and if he desires to witness the deep-sea fishing for ling, with its full

equipment of sheds for drying, agents' houses, and temporary huts for the

boatmen, and all the bustle and activity of those who are obliged to catch

the few calm days of summer in seeking their bread upon the waters, he will

from Whalsey sail over to the little cluster of islands called the

OUTSKERRIES, where this fishing is pursued on a large scale.

19. FETLAR, an island from

five miles to six miles and a half long and five miles broad,

notwithstanding the fertility of its valleys and the number of its ancient

law-tings, and its steep cliffs at Lamboga being the resort of the peregrine

falcon, has little to recommend it to the tourist, unless he be a geologist.

Its southern shores consist of a ridge of gneiss, succeeded, between Urie

and the Bay of Tresta, by a broad belt of alternating beds of serpentine,

diallage rock, micaceous schist, and chlorite schist, to the north of which

rises the high serpentine vord or Wardhill of Fetlar, which is in like

manner flanked on the farther side with a similar succession of rocky beds

intermixed with talcose schist, and exhibiting occasionally a conglomerate

structure. From Fetlar to the handsome seat of Belmont (Thos. Mouat, Esq.)

in Unst, the distance is about six miles, being across a channel diversified

with several sea-holms. Guarded by the tumultuous rousts and tides in Blomel

and Uyea sounds, and on the north of Scaw, Unst presents but few interesting

external features, except its sea-coast precipices, above which its bleak

yellowish serpentine hills rise with a most forbidding and dreary aspect.

Uyea island is, however, the great resort of shipping in pursuit of the

deep-sea fishing, which also rendezvous here for the supply of goods to the

several fishing stations in the neighbouring isles; and Buness, the

residence of T. Edmonston, Esq., near the head of Balta Sound, on the

eastern coast, will long be celebrated as having been the site where the

French philosopher Biot, and his successor Captain Kater, in the years

1817-18, carried on their experiments for the purpose of determining, in

this high latitude, the variation in the length of the second's pendulum.

The island also abounds in stone circles and barrows; and at Cruciefield the

great juridical assemblies of Shetland were anciently held, previous to

their removal to the Vale of Ting-wall, on the mainland.

But the great treasure of

Unst is its chromate of iron, a mineral which of late years has become an

object of commercial importance, on account of the use to which it has been

converted, in affording the means for procuring a yellow pigment for the use

of the arts, and its application to the dyeing of silk, woollen, linen, and

cotton. It was formerly obtained, at a high price, chiefly from America; but

Dr. Hibbert, in the year 1817, discovered it strewed in great loose masses

on the surface of the hill of Cruciefield, at Hagdale, and Buness, and in

several other places in the vicinity of Balta Sound in Unst, and succeeded

in satisfying the proprietors of its value. It was first seen in insulated

granular pieces left loose on the surface from the disintegration of the

rocks of serpentine which enclosed it; but it was soon traced out as

disseminated in thin ramifying veins from two to six inches in breadth, and

ultimately in beds of much greater magnitude. The ingredients of the

serpentine rock are silex, magnesian earth, alumen, oxidulated iron, and

chromate of iron; the two latter also being found in grains as minute as

gunpowder, and therefore appearing as component parts of the rock, as well

as in detached masses and veins. Associated with these occur potstone and

indurated talc, with beautiful specimens of amianthus and common asbestus;

and at Swinaness, a headland at the northern entrance of Balta Sound, Dr.

Hibbert also discovered a very rare pure white and transparent mineral, the

native hydrate of magnesia, which, on analysis, presents 60.75 parts of pure

magnesia, and 30.25 of water, in 100 parts.

Besides the other kinds of

sea-fowl with which this island abounds, the hill of Saxaford, on the

north-cast side, which is estimated at a height of 600 feet, and which is

composed of micaceous and talcose slate, is noted as the occasional resort

of the rare skua gull (Cataractes vulgaris) which breeds also in Foula, and

on Rona Hill, in the mainland.

20. Yell is a dull

uninteresting island, six miles broad by about twenty miles long, wholly

composed of long parallel ridges of gneiss rocks, of a heavy uniform course

from southwest to north-east, and sloping gradually towards the shore. It

is, however, an excellent fishing station ; and, from the days of George

Buchanan, has been noted for its booths, or small warerooms, filled with all

sorts of vendible articles, now chiefly imported from Scotland, but

anciently from Hamburgh and Bremen. In the troubled sea of Yell Sound, and

the vicinity of its little holms or islets, distinguished for their fine

succulent pastures, and as the breeding-places of the tern, parasitic gull,

and eider duck, herring shoals and swarms of young sillocks are always to be

seen; and perhaps the tourist may witness the pursuit and capture of a drove

of ca'ing whales, as the Delplzinus deductor is styled in Shetland, which

occasionally appear off these coasts in a gregarious assemblage of from 100

to 500 at a time. Their seizure is always attended with great excitement and

cruelty; and, although the blubber affords a rich prize to the captors,

nothing can better display the debased state of the husbandry in some of

these north isles, than the fact that the carcases of the whales are in

general allowed to remain untouched, tainting the air until they are

completely devoured by the gulls and crows. [We understand that the carcases

are now in some instances better estimated, and that the bones are purchased

for exportation as hone manure.]

Yell boasts of no less than

eight ancient circular burghs; and, at one time, of twenty chapels or

religious houses, although they are almost all completely in ruins. All the

ecclesiastical buildings of Hialtland appear to have been devoid of the

least show of ornament; for the pointed arch, pinnacled buttress, or the

rich stone canopy, never dignified any of them. A tall, rude tower was their

only, and that but an occasional, appendage: but, from their great number,

they would appear often to be not so much parish churches as the private

oratories of the independent udallers, or the free-will offerings of foreign

seamen, erected in fulfilment of their vows to Our Lady, St. Olla, St.

Magnus, St. John, or some of the other saints of the calendar, whose

intercession was believed to have saved them from shipwreck. Crossing from

this island to the central districts of the mainland, the tourist will find

but little to reward his toil, if he attempt to thread his way among their

endless swamps, firths, and uninteresting tame hills, composed chiefly of

gneiss, with a few interstratified beds of limestone, the latter of which

however, where they occur, bestowing a superior verdure and richness on the

pastures. A few gentlemen's seats, some of them, as at Busta, having walled

gardens, and, for the climate, rather large-sized trees, though no bigger

than bushes, may be seen: but in general the country is tenanted chiefly by

flocks of the little wild yet fine-fleeced sheep, for which Shetland is

famed, with here and there a few patches of corn land, tilled by the ancient

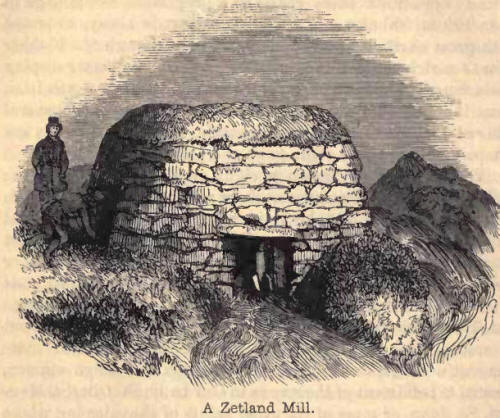

Scandinavian single-stilted plough, the produce of which is ground into meal

by the no less primitive simply-constructed water-mill peculiar to the

country, or the still more antique hand-mill or quern. The richer pastures

of the sea holms, which, by strict laws, were wont to be preserved from

being encroached on by the passing stranger, always exhibit a more

lively green than the

adjoining hills; and the bold granitic shores, crowned with the remains of

ancient burghs or round towers, (like that of Cullswick, on the

south-western coast), would, but for their continued recurrence under

similar forms, be considered grand and imposing. Around the more lofty and

inaccessible headlands, the voyager may yet descry solitary couples of the

royal hawks, which can bear no other birds, even of their own species, to

occupy the same cliff with them, hovering over their young; and he may be

told that old acts of parliament specially reserved them, from all ordinary

grants, for his majesty's use, according to ancient custom. The goshawk, or

Falco palumbarius, was the object in general of the falconer's search; but

the bird held in chief estimation was the Falco perigrinus niger, of which a

single pair is believed to have always bred in Fair Isle, and others in

Foula, Lamboga, Fitfiel, and Sumburgh Head.

21. To the naturalist,

view-hunter, and commercial gentleman, studious of knowing the arcana of the

Haaf, or deep-sea fishing, the north-western portions of the Mainland,

consisting of the parishes of Aithsting, Walls, Sandness, and North Ma-vine,

present many objects deserving of a visit. At Aithness, SouIam Voe, Stennis,

Hillswick, Feideland, Vementry Island, and many other places, the cod, ling,

and tusk fisheries have been pursued for a very long period; and in ancient

times, from the 1st of May to the 1st of August, vessels freighted with

goods for exchange of fish, were constantly arriving from Hamburgh, Lubeck,

Bremen, and Denmark, and latterly from Scotland and England. In our

introductory paper to this work (p. 14) we have given a short sketch of the

Dutch fisheries in Shetland, to which we refer; and our limits permit us

only to add, that the foreign merchants, on landing, always found booths

ready for their use, or they were permitted to erect shops for the display

of their wares, for the ground-rent of which they paid the native

proprietors at a most exorbitant rate. Besides books, lines, nets, and

various kinds of grain and fruits, cloths, linens, and muslins, were the

articles tendered to the fishermen, who bartered for them their fish, both

in a wet state, and, under the name of stock-fish, such as were dried in

their stone buildings, called skoes, to which also they added stockings,

wadmel, horses, cows, sheep, seal-skins, otter-skins, with butter, and oil

extracted from the livers of fish.

The men employed at the haaf,

or the fishing station most distant from the land, are generally the young

and hardiest of the islanders. Six tenants join in manning a boat, their

.landlords importing for them frames, ready modelled and cut out in Norway,

which, when put together, form a yawl of six oars, from eighteen to nineteen

feet in keel, and six in beam ; and which is also furnished with a square

sail. After waiting for a fair wind, or the ceasing of a storm, the most

adventurous boatmen give the example to their comrades, starting off in

their yawl, and taking the first turn round in the course of the sun, when

they are instantly followed by the whole fleet, each boat of which strives

to be first at the fishing station, often forty or fifty miles away. Arrived

at the ground, they prepare to set their tows, or lines, provided with ling

hooks. Forty-five or fifty fathoms of tows constitute a bught, and each

bught is fitted with from nine. to fourteen hooks. Twenty bughts are called

a packie, and the whole of the packies a boat carries isa fleet of tows. The

fleets belonging to the Feideland haaf are so large as seldom to be baited

with less than 1200 hooks, provided with three buoys, and extending to a

distance of from 5000 to 6000 fathoms. The depth to which the ling are

fished for varies from fifty to one hundred fathoms; and after the lines are

all set, which, in moderate weather, requires from three to four hours, the

fishermen rest for two hours, and take their scanty sustenance: their

poverty, however, allowing them no richer food than a little oatmeal and a

few gallons of water; for the Shetlanders can rarely supply themselves with

spirits.

At length one man, by means

of the buoy rope, undertakes to haul up the tows; another extricates the

fish from the hooks, and throws them in a place near the stern, named the

shot; a third guts them, and deposits their livers and heads in the middle

of the boat. Along with the ling, a much smaller quantity of tusk, skate,

and halibut are caught, the two last being reserved for the tables of the

fishermen ; and six or seven score of fish are reckoned a decent haul,

fifteen or sixteen a very good one, and when above this quantity the

garbage, heads, and small fish are thrown overboard, the boat,

notwithstanding, being then sunk so far as just to Lipper with the water. If

the weather be moderate, a crew is not detained longer than a day and a half

at the haaf ; but as gales too often come on, and as the men are reluctant

to cut their lines, the most dreadful consequences ensue, and many of the

poor fishermen never reach land. On their return to shore, the boatmen are

first engaged in spreading out their tows to dry; then some of them catch

piltocks with a rod and line, or procure other kinds of bait, at a distance

from the shore; while others, again, mend the tows and cook victuals for the

next voyage to the haaf: thus, in the busy fishing season, so incessant and

varied are the demands on the fishermen's time, that they rarely can snatch

above two or three hours in the twenty-four for repose. Their huts are

constructed of rude stones without any cement, covered with thin pieces of

wood and turf for a roof, and the dormitories consist only of a little straw

thrown into a corner on the bare floor, where a whole boat's crew may be

found stealing a brief rest from their laborious occupations.

22. Feideland, the most

northerly of these great fishing stations, is a long narrow. peninsula,

jutting far out into the ocean, distinguished, as is every place having the

same Scandinavian name, by its superior green pastures : everywhere about it

the coast is awfully wild ; and the peninsula, broken on each side into

steep precipices, exhibits now and then a gaping chasm, through which the

sea struggles, while numerous stacks rise from the surface of a turbulent

ocean, the waves beating around them in angry and tumultuous roar.

23. Sailing westward by Uyea

Island to Roeness Voe, the stranger will obtain a complete view of the vast

impending cliffs of granite, cut into numerous eaves and arches open to the

Atlantic, that form the farther coast of North Mavine. Above these rises the

red barren scalp of Roeness Hill to a height of 1447 feet, which, though

steep, abounds with alpine plants, and from the circular watch-tower on its

summit commands a most extensive and instructive view, from the peaks of

Foula to the broad bay of St. Magnus and the hills of Unst. In the district

near at hand there is a chain of deep circular lakes, which, when the sun

shines bright, reflect on their bosom every one of the rugged and dreary

crags by which they are surrounded ; sky, rocks, and heath limiting the

horizon on all sides ; no marks of man's labour appearing, but tranquillity

pervading the scene, except where the stranger, gaining the summit of a sea

cliff, beholds suddenly the tumbling billows of the ocean, and thousands of

insulated rocks whitened with innumerable flocks of sea-fowl, and hollowed

out at their base into caverns, the secure retreats of otters and seals.

At Doreholm, a spacious arch

of seventy feet, and the Isle of Stennis, a great fishing-station belonging

to Messrs. Cheyne, which are exposed to the unbroken fury of the Atlantic,

enormous masses of rock have been bodily heaved up, and removed to

considerable distances by the waves, while, on the summit of the cliffs in

that neighbourhood, especially at the Villians of Ure, the tired feet of the

traveller will be unexpectedly refreshed with a walk on the finest and

softest sward, to which the compliment, often paid to some rich vale of

England, may well apply—"Fairies joy in its soil." It is the favourite

promenade of the inhabitants, especially on the fine summer evenings ; nor

is this pleasing bank, on which numerous sheep are continually feeding, the

less interesting from being encircled with the harsher features which

Hialtland usually wears, and perched on the top of naked, reds precipitous

crags, on which a rolling sea is always breaking.

24. Though troubled is the

channel which separates PAPA Sroua, the southernmost islet and promontory of

St. Magnus Bay, from the mainland, the tourist, if possible, should not omit

paying a visit to its grand porphyritic stacks, and magnificent underground

rocky excavations which the inhabitants visit at certain seasons armed with

thick clubs, and well provided with candles, in search of the seals which

breed in them. When attacked with these weapons, the poor animals boldly

advance in defence of their young, and often wrench with their feet and

teeth the clubs out of their enemies' hands ; but in vain : escape is

denied, and these gloomy recesses are stained with blood, and numbers of

dead victims are carried off in boats.

Papa Stour, like Iona and

some others of the Hebrides, was the resort, in the earliest period of

Christianity, of certain Irish priests or papae who fled here either for

refuge from some commotion in their own country, or came over to proclaim to

the heathen the glad tidings of the Gospel of God's grace. In Shetland,

three islands bear the name of Papa, Papa Stour being the largest ; and this

island is the only part of the country where the ancient Norwegian amusement

of the sword-dance has been preserved, and where it still continues to

beguile the tediousness of a long winter's evening. We have no room for a

description of it, and must refer our readers to Sir Walter Scott's

"Pirate," and Dr. Hibbert's minute account.

25. The bold island of

Fughloe (Foula) or Fowl Island, is the last we have room to notice in this

sketch. It presents the appearance, when viewed from the sea, of five

conical hills rising from the waters at the distance of eight leagues west

of the mainland, and towering into the sky. They are all composed of

sandstone, set on a primitive basement; and the highest, called the Kaim, is

estimated as of an elevation of 1300 feet.

There is now little doubt

that this island is the Thule descried by Agricola from Orkney, from the

north-western parts of which it is often visible. It was one of the last

places in which the pure Norse language was spoken; in general, the parish

schoolmaster officiates as a sort of pastor to the inhabitants, except when

the minister of 'Wes visits them, once a-year, for the purpose of

celebrating the communion.

"The low lands remote from

the sea," says Dr. Hibbert, "are frequented by parasitic gulls, which build

among the heather. The surface of the hills swarms also with plovers,

Royston crows, scapies, and curlews. On reaching the highest ridges of the

rocks, the prospect presented on every side is of the sublimest description.

The spectator looks down from a perpendicular height of 1100 or 1200 feet,

and sees below, the wide Atlantic roll its tide. Dense columns of birds

hover through the air, consisting of maws, kittywakes, lyres, sea-parrots or

guillemots ; the cormorants occupy the lowest portions of the cliffs, the

kittywakes whiten the ledges of one distinct cliff, gulls are found on

another, and lyres on a third. The welkin is darkened with their flight ;

nor is the sea less covered with them, as they search the waters in quest of

food. But when the winter appears, the colony is fled, and the rude harmony

produced by their various screams is succeeded by a desert stillness. From

the brink of this awful precipice the adventurous fowler is, by means of a

rope tied round his body, let down many fathoms ; he then lands on the

ledges where the various sea-birds nestle, being still as regardless as his

ancestors of the destruction that awaits the falling of some loose stones

from a crag, or the untwisting of a cord. It was formerly said of the Foula

man, `his Butcher (grandfather) guid before, his father guid before, and he

must expect to go over the Sneug too."

One of the highest rocks is

occupied by the bonxie or skua gull, the terror of the feathered race; but

he is so noble-minded as to prefer waging war with birds larger than

himself: even the eagle forbearing to attack lambs in the skua's presence.

NATURAL HISTORY OF THE ZETLAND

ISLANDS.

26. The natural history of

these islands so greatly resembles that of Orkney, that, after the full

details we have given of the latter, it would be less necessary for us to

enter minutely on that of the former groups, even had we room to do so. The

plants of Shetland differ less from those of the north of Scotland and

Orkney in the number of new species, than in the more limited vegetation,

and the absence of species elsewhere abundant, especially of the ligneous

and larger herbaceous tribes; while they no doubt, on the other hand,

exhibit many approaches to an identity with the Arctic Floras of Spitzbergen

and Greenland. Similar remarks apply to the zoology of these islands. We

have not yet been enabled to institute a proper comparison, with any degree

of correctness, between the plants of Shetland and those of Great Britain in

general; and we regret not having it in our power, as yet, to present our

readers with the results of a careful examination of the effects which the

high latitude and exposed situation of these islands have produced on the

size and geographical distribution of their vegetables. [In our introductory

remarks on the resources of the Highlands, and in the preceding Itinerary,

we have said enough, for such a work as this, on the fishes of the Shetland

seas; and to these details we refer.]

But to the geologist we can

say, that if Scotland in general be the best nursery for the British

botanist, Shetland, undoubtedly, presents the most varied and best exposed

field for tracing the relations of rocks to one another, and acquiring

enlarged and correct apprehensions of the forms under which they were

originally consolidated, as well as the subsequent changes they have in many

instances undergone. The variety of the rocky materials of these islands is

indeed great; and the deep indentations of the sea, and the extensive ranges

of precipices all round the coasts, enable the explorer to obtain easy and

satisfactory access to them ; while the narrowness of their rocky zones, and

the prolonged courses of some of the beds along the headlands and islets,

extending out into the contiguous ocean, leave us at no loss to conclude

that the whole group are but the wrecks or small remaining portions of a

high ridge or breastwork of stone, which may have originally extended not

only to the adjoining mainland of Scotland, but also, in all probability, to

the opposite continent.

In the preceding remarks we

have noticed the positions of several particular rocks and minerals; and it

now only remains for us to present our readers with a general sketch of the

geology of the whole cluster of the ZetIand Islands, such as they may find

useful in directing them where to seek for specimens for scientific

collections, or the examination of the country.

The central ridges of the

south-eastern portion of the mainland, extending from Fitfiel Head to

Hawksness, and composing the range of the Cliff Hills, consist chiefly of

primitive clay slate (the phyllade of the French), with a few quartz and

hornblende beds amongst it; but with the exception, however, of a small belt

of land, stretching from Quendal Bay in a north-westerly direction to

Spiggie (a district about five miles in length by one in breadth), which is

formed of a sienite, denominated by Dr. Hibbert, from the prevalence of a

mineral disseminated through it, epidotic sienite. To this clay slate

deposit succeeds, on the eastern side of the island, a series of blue and

reddish sandstones, presenting a good deal of the aspect of hard

unstratified quartz rock in their lower masses; but decidedly arenaceous and