|

"As when a shepherd of the

Hebrid Isles,

Placed far amid the melancholy main;

{Whether it be lone fancy him beguiles;

Or that aerial beings sometimes deign

To stand embodied, to our senses plain),

Sees on the naked bill or valley low,

The whilst in ocean Phoebus dips his wain,

A vast assembly moving to and fro,

Then all at once in air dissolves the wond'rous show."

Thomson.

General features; Emigration;

Mr. 'Matheson's Impros ements; Botany and Geology, foot-note, 1.—Produce ;

Fisheries; Distance of Inns; Aspect of the Islands, 2. Cave in Lewis;

Antiquities; 'Monastery and Church at Rodel; Stone Circle at Loch Bernera,

3.—Stornoway; Stornoway Castle, 4.—Implements; Packets; Steam-boat; Road and

Inns, 5.—Climate of Long Island, 6.—Storms, 7.—Scenery, 8.—Occurrences in

Rebellion of 1745, 9.—Prince Charles' Wanderings, 10.

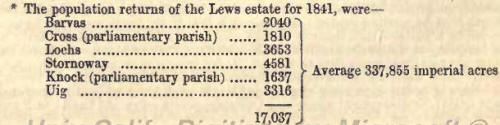

1. UNDER the general

denomination of the Long Island are comprehended that large group of islands

called the Outer Hebrides, the principal of which are Lewis, or Lews (the

land of Leod or M'Leod, and commonly styled the Lews), and Harris, North and

South Lf ist, Benbecula, and Barra; and the whole length of which, from

Barra-head to the Butt of Lewis, is about 120 miles. The northern part of

this great chain, viz. the Lews (a tract of ground about forty miles in

length, and in some places twenty-four in breadth) is in the county of Ross;

Barris, though in the same island, and all the other islands belong to the

shire of Inverness. Lews, long ago won and retained by the sword as an

appendage of the Seaforth family, " high chiefs of Kintail," and head of the

Clan Mackenzie, has now, by purchase, passed into the hands of James

Matheson, Esq. of Achany and Lews, Member of Parliament for the combined

counties of Ross and Cromarty, who is himself a descendant, and the head of

the very ancient Celtic race who possessed the Mackenzies' country about

Loch Duich and Lochalsh, in the reign of Alexander III. (A. D. 1264).

Harris, separated from the Lews by a narrow isthmus of about six miles in

width, formerly the property of an old and distinguished branch of the

Macleod family, now belongs to Lord Dunmore; Lord Macdonald possesses the

whole of North Uist; the island of Benbecula, and great part of South Uist,

formerly the property of Macdonald of Clanranald, is now that of Colonel

Gordon of Cluny; and the remainder of South Uist is the inheritance of

Macdonald of Boisdale; whilst Barra, with its surrounding isles, belongs

also to Colonel Gordon. The whole of these islands, though now completely

destitute of wood, with the exception of some ornamental plantations around

Mr. Matheson's residence at Stornoway Castle, and a thriving plantation of

oak, ash, rowan-tree, and poplars, at Rodel House, in Harris, shew, by the

large roots and stems found in the mosses and along the water courses, that

they were once well clothed with trees. The surface now (as if a great

change of climate had ensued) is everywhere covered with stunted heather and

moss, and extensive peat bogs. The islands are all more or less hilly,

though not rising to any considerable size, except one hill in Lews, and in

the district of Harris where the mountains attain the extreme height of from

2000 to 3000 feet, are there more crowded together, and more rocky and

barren than in the other islands. The splintered and spiry granite rocks in

some parts of Harris, present scenery of the most picturesque character. To

the south of the Sound of Harris, the hilly ground is chiefly confined to

the east coast, and is succeeded by a wide tract of flat peat moss. The

western shore of the islands consists of a sandy soil, yielding good arable

ground. There are here prodigious tracts of shell sand, miles in breadth,

and the downs along them are covered with the richest vegetation, and

present a most brilliant mass of colouring, from the profuse and luxuriant

flowers of the white clover, intermingled with innumerable daisies,

butter-cups, and diminutive meadow plants.[In the ruts of streams,

lacustrine islets, and clefts of rocks throughout these islands, a few

stunted stems may occasionally be seen of the common birch, the broad leaved

elm, the rowan-tree or mountain ash, the hazel and aspen, with a few

dwarfish willows—Rebus cortylifolius, Rosa tomentasa, Lonicera Periclymcnum,

and ifederallelix, aretheonly shnihs worth mentioning—(ProfessorMacGillivray.)

Thalictrum.4lpinunt is almost the only Alpine plant to be found in Harris.

Ajuga yrantidales, Osmunda reyalis, and Pinguicula lusitanica occur along a

rocky burn about a mile south of Stornoway; but Menziesia cervlea is not now

to be found in the Siiant Isles. Dr. Balfour, in his report to the Edinburgh

Botanical Society in 1811, remarks, that "there is hardly a true Alpine or

rare plant to be found in the Long Island. Tire hanerogamous species amount

to 316, of which 15 or 1-21 part are true ferns, and .2 belong to the order

Jitters L,copodiacerc and B.quisitacere. The geology of the district is

equally simple—the whole islands being composed of various modifications of

a hard gneiss, with but here and there a basaltic or trap dyke; and in one

peninsula to the eastward of Stornoway, a small deposit of old red sandstone

conglomerate—the remains of those extensive sheets of sandstone which once

united it with the masses of the same rock on the Scottish mainland. In the

outer Hebrides there seems to be an unusual scantiness of the debris and

gravel beds which cover the rest of the kingdom; but there are in a few

places sea margins and ancient terraces, and sonic beds of deep clay,

indicative of the satue.t,gencies which elsewhere have given rise to the

great boulder clay and drift gravel of the more recent tertiary deposits.

These outer ridges of primary gneiss rocks are in fact most interesting, as

being in all probability the relics of that great line of elevated

mountains, which, ere the last change of level of the ocean in this

hemisphere, seems to have extended from the coasts of Spain and Portugal,

northwards along the Welsh, Cumbrian, and western side of Scotland, and

whence dipped eastwards the shelving strata of secondary rocks which

extended to the great European plains, across the bed of what is now the

German and Baltic seas.] In summer this part of the country presents an

agree able and smiling aspect; but in winter it shares the general

desolation of the adjoining islands. On this side the great mass of the

population of the southern islands is collected; elsewhere the country is

left uninhabited, except in the immediate vicinity of the bays and arms of

the sea. Poverty is but too prevalent among the people—a mixed Celtic and

Scandinavian race —shell-fish forming almost their only subsistence during

the latter summer and earlier autumn months. Yet, under all their

privations, these poor people are hardy, cheerful, and contented. Their

number is redundant; for which the only remedy appears to be a well-arranged

system of progressive emigration.

A deal of angry discussion

has of late years taken place on this subject, one party maintaining that

there is no necessity for emigration, were the people duly fostered and

instructed how to avail themselves of the resources within their reach, in

the sea and land, and that it is the duty of the landlords to do everything

for them, save turning them away from their native holdings. Another party,

on the contrary, maintain that where a population has within 60 years

doubled itself, and the great means of their support, in later times, (the

kelp trade), has vanished, whereby the lower orders have become pauperized,

it is vain to expect that they can be recovered, except by their engaging in

new employments, (as the deep-sea fishing), or betaking themselves to new

abodes; and that no race of landowners can long afford to let their

possessions be occupied by others totally rent free. Whatever the

necessities, on speculative views, of some of the proprietors may induce

them to do, it is fortunate for the great district of the Lews, that it is

now in the hands of a gentleman both able and willing to give the

experiment, of what can be effected by local improvement and exertion, the

fairest and most ample trial. The late proprietrix, the Honourable Mrs.

Stewart Mackenzie, (daughter of the last Lord Seaforth), and her husband,

the Honourable S. Mackenzie, Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands,

than whom the Highlanders had no more warm or intelligent friends,

introduced many spirited improvements (which, however, long absence latterly

interrupted), and laid a commencement in the formation of roads and bridges

for a regular system of drainage, and an internal communication of the

districts with one another. Mr. Matheson has followed up those measures on a

more extensive scale, under the superintendence, for a time, of a

persevering, though sanguine agriculturist, the late Mr. Smith of Deanstoun.

Already be has drained, trenched, enclosed, and brought into culture, nearly

2000 acres of waste land, and of which a large proportion is now under crop,

and let to tenants.

There are, we believe, about

a hundred times as much more reclaimable ground on his vast property. To

overtake its culture must be the work of generations; but meanwhile, the

pasturage of the whole is being greatly improved. The most humble of the

tenants (called crofters, from having only small plots or crofts to

cultivate) have got leases, and are improving their land according to a

regular plan—the money being advanced by the proprietor in the first

instance, on an annual charge of 5 per cent. interest for the use of it.

Besides improving and repairing 80 miles of roads constructed by his

predecessors, Mr. Matheson has also formed about 100 miles of new roads, and

erected upwards of twenty bridges, thus rendering almost every corner of the

island accessible to carriages, exclusive of the improvements in the town of

Stornoway, to be afterwards noticed; and, besides his encouragement of the

fisheries, he has likewise granted feu rights of building-stances to his

villagers on easy conditions—simply binding their to certain general police

and sanitary regulations; to perfect the drainage he has erected an

extensive brick and tile work, driven by steam, at a locality where the

finest clay exists, in an inexhaustible bed; he has formed extensive canals,

or general drains, to carry away the moss water where the surface is low;

has planted about 800 acres with forest-trees, and has introduced improved

breeds of horses and cattle. By a bold and judiciously-managed experiment,

Mr. Matheson has likewise succeeded in raising from seed, in several places

in the close vicinity of the sea, the celebrated tussac grass from the

Falkland Islands, a most invaluable succulent plant for all sorts of

ruminant animals, and which, should it continue to thrive, will of itself

most amply reward his patriotic exertions. Under such auspices, the

capabilities of the soil and climate, and the power and energy of the people

to arouse themselves from their present abject condition, and the occasional

risk of starvation, from failures in their potato and grain crops, will be

fully tested, and the policy or impolicy of emigration on a great scale

demonstrated.

2. The chief product of these

islands has hitherto been kelp, of which several thousand tons are annually

exported; sea-ware being peculiarly abundant, owing to the very extended

line of sea-coast, produced by the arms of the sea, by which the Long Island

is indented, and the numerous rocks and islands with which the coasts and

the passages or straits between the larger islands abound. As an example of

the intricate winding of the salt-water lochs, and the number of islands

with which they are studded, we may refer to Loch Maddy in North Uist, which

covers about ten square miles, and yet the coast line of its numerous

windings, creeks, bays, and islands, approaches to three hundred miles. The

cod, ling, and herring fishery, are the other chief sources of subsistence

for the over-abundant population of these remote islands. A London company

have an agent regularly settled at Loch Roag for the purpose of transmitting

lobsters to the tables of the London gourmands. A vessel sails weekly for

the Thames, constructed so as to contain a large well, in which the fish are

conveyed alive, and in this way an average of 15,000 lobsters are sent every

week to the London market. Sometimes the number has been as great as 40,000!

The agent at Loch Roag distributes from £3000 to £4000 per annum among the

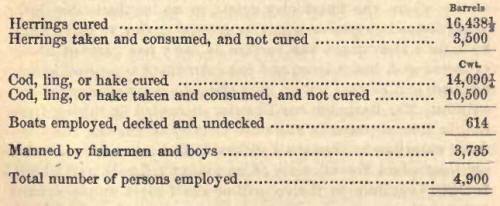

men engaged in this traffic. We are delighted to observe, in the Report of

the British Fisheries Commissioners for 1849, that the Long Island returns

stand as follows:—

The formation of a harbour at

West Loch Tarbet, in Harris has proved of the utmost benefit in the

prosecution of the fisheries. With the wages they earn in fishing, and the

burning of kelp, the poor cottars contrive to eke out the rents of their

crofts, which of themselves, at least as formerly managed, are barely

sufficient for the maintenance of the persons who labour them. To these

means, shell-fish, which are found in great variety and abundance, form a

valuable addition. The quantities of these, particularly of cockles, on the

shores of the most parts of the Long Island, is almost inconceivable. Sheep

are pretty numerous ; but these islands are more celebrated for their black

cattle and ponies, of which great numbers are annually exported. Red deer,

grouse, woodcocks, plovers, and, in some few places, rabbits, are plentiful;

and all the varieties of sea-fowl that frequent the coasts of Scotland are

found in great abundance, as also eagles, hawks, and other carnivorous

birds.

Besides the small tenants,

there are in most of the islands tacksmen, who rent large farms, chiefly

well educated and gentlemanly men, and distinguished for their hospitality.

The hills are generally too

heavy and smooth in their outline, and the cliffs too low, to exhibit much

interesting scenery. Indeed, Lewis and Harris alone present any peculiar

features; as the openings of Lochs Seaforth and Clay, in the vicinity of

Gallanhead and the Butt of Lewis, and the coasts and interior and Sound of

Harris; and also the islands of Bernera and Mingalay, at the south of Barra,

in the latter of which the rocks are said to be 1200 or 1400 feet in height,

and tenanted by prodigious flocks of sea-fowl. Each kind maintains its own

peculiar portion of the rock. Their serried ranks of white breasts and red

bills, when at rest, are not less remarkable than their dissonant clamour on

being roused, when they darken the air with their fluttering masses. But the

bird's-eye view from any of the hills is curious, owing to the strange and

intricate intermixture of land and water. In addition to the arms of the sea

by which the Long Island is cut up, it is also intersected (particularly to

the south of the Sound of Harris) with numerous fresh-water lakes. These are

generally shallow, and their waters are tinged of a brown colour from the

peat, but they abound in trout. They have seldom any inlets or feeding

streams, being in many cases mere deposits of rain water—in fact, brooks are

rare, except in the Lewis

3. Of the objects worthy of

the traveller's attention, one of the principal is the remarkable cave near

Gress, in the parish of Stornoway, which used to be annually invaded by a

body of the natives, to despatch the seals, which flock hither in great

numbers. It is upwards of 200 yards in length, and is partially covered with

stalactite, like Strathaird's Cave in Skye.

As respects antiquities,

numerous remains of the circular towers, called Dunes or Burghs, are to be

seen on the hills and islands in the lochs. To these last, causeways often

conduct from the shore, raised nearly to the present surface of the water.

Of the circles of stones so common in the Highlands, and generally

designated as Druidical, there are also a great number, called by the

natives fir bkreiq, or false men, from their resemblance, when seen at a

distance, to the human form. The largest collection of them occurs near Loch

Bernera, in Lewis, and which has been figured and minutely described by Dr.

Macculloch (Western Isles, vol. i., p. 185). The principal structure

consists of a wide circle, with a large central stone, from the

circumference of which branch off four lines of upright stones, opposite

each other in a cruciform shape. The extreme points of two of these lines

are about 650 feet apart, and of the other two about 200 feet. One of those

lines consists of a double row of stones, which, like the others, average

about four feet in height. There are also some ruins of very early Christian

churches, hermits' cells, and other religious houses, in these islands, and

of a few nunneries—the last of which are now characteristically called "

Teagh nan cailichan dhu "—" The houses of the old black women." The churches

and most of the smaller chapels appear to have depended immediately on the

monastery at Rodel, or Rowadill, in Harris, founded—as remarked by

Spottiswoode, in his Account of the Religious Houses, appended to Keith's

Catalogue of the Scottish Bishops—" by Macleod of Harris, and situated on

the south-east point of the island, on the sea-coast, under Ben Rowadill."

It was one of the twenty-eight monasteries in Scotland belonging to the

Canons Regulars of St. Augustine, who here, as at Oronsay and Colonsay, were

most likely superinduced, through the influence of Rome, upon more ancient

and simple foundations of St. Columba's disciples. The establishment of this

monastery (dedicated to St. Clement) is usually ascribed to King David I,

but, we believe, on no good authority. The church is still in tolerable

repair; it is cruciform, with a tower about sixty feet high, forming one

side of the transept, and which is conspicuous from a great distance. On

Norman foundations, the superstructure is of Early English; the altar window

is simple but beautiful, and the capitals of the columns have grotesque

figures and carvings like those of Iona. There are two nude figures; and, as

Dr. 1lacculloch remarks, "the sculpture presents some peculiarities which

are well worthy the notice of an antiquary, and, from their analogy to

certain allusions in Oriental worship, are objects of much curiosity."

The most entire, indeed

almost the only, castle is on the island of Barra, and was the ancient

residence of the Macneils. It is a sort of fort, standing on an islet in

Chisamil Bay. Walls about sixty feet high enclose an irregular area, within

which are a strong square keep, and other buildings. There is a dock of the

exact dimensions of a galley, and good anchorage on all sides of the rock.

Martin was informed that, in his time, this building was reputed to be of

500 years' standing. In the island of Eriskay, in the Sound of Barra, is

another picturesque ruin, called Castle Stalker, well known to sailors as a

landmark.

4. The only town is Stornoway,

on the east coast of Lewsa burgh commenced by James VI. to civilize the

natives—on reaching which, the stranger is surprised at finding so

considerable and flourishing a place in so remote and uninviting a corner.

It is a fishing establishment, with several streets of substantial and

slated houses, and numerous shops, inns, and public-houses. There is a

,Masonic Lodge, spacious and elegant Assembly Rooms, with a handsome

Reading-room. With the surrounding tract of cultivated fields and

plantations, and some remains adjoining of an old castle, said to have been

dismantled by Cromwell's soldiery—and the modern castle, separated only by a

narrow channel of the bay from the town—and its spacious piers and capacious

bay, protected by two low headlands and an island, Stornoway forms a

remarkable relief to the prevailing dull, barren, and dreary appearance of

the country. Occasionally, from the crowded shipping, it is a place of much

life and gaiety. The town's people are distinguished by an eager pursuit of

commerce, and the shipping belonging to the port is extensive. It is the

seat of a district Sheriff-court. The seabeach consists of fine shingle,

well adapted for drying fish upon, and on which many tons of fish, piled up

in great heaps, may often be seen in various stages of preservation.

Besides promoting the

cleanliness and comfort of the town by every means in his power, such as

founding gas and water companies, and taking up half the stock of

each—laying down a Morton's patent slip, worked by steam, and which will

haul up a vessel of 800 tons—constructing a market place for the sale of

butcher meat and vegetables to the shipping—purchasing up and completing a

neat Episcopal chapel built by subscription, but which had been encumbered

with debt ;—_Mr. Matheson of Lews has also taken a deep interest in the

cause of education generally throughout the island, and especially at

Stornoway. In the year 1847, he built an industrial female school, with an

endowment for the schoolmistress, to which a handsome additional

contribution is made by the inhabitants. At this seminary Ayrshire flowering

needlework is taught, by means of which the native females are already, like

their sisters in the north of Ireland, enabled to support themselves, and

that by an employment tending directly to soften their characters and

improve their tastes. If this branch of industry shall get fairly rooted, we

presume the straw plait manufacture will follow, as in Orkney. Several

schools have likewise been built and endowed throughout the island, but

hitherto the attendance has been retarded by a disinclination on the part of

the parents to lose the services of their children in herding, and an

apprehension that education may dispose them to try to better themselves by

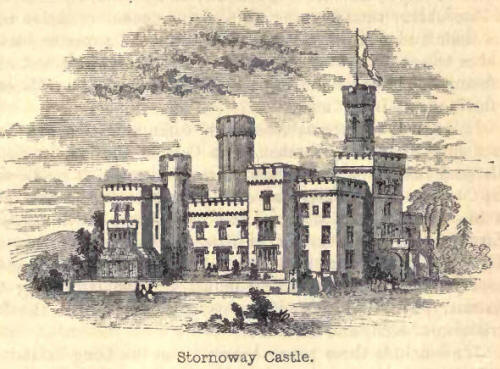

emigration. To attach himself still farther by personal residence to his

adopted island and new tenantry, Mr. Matheson has likewise erected a

splendid mansion-house, Stornoway Castle, on the site of Seaforth Lodge. It

is a very large building in the castellated Tudor style, erected chiefly of

granite found in the neighbourhood, with white sandstone dressings from

quarries near Glasgow. The south facade measures 153 feet in length; the

eastern or entrance facade 170 feet. The building is of various elevations

and projections, and being flat-roofed and battlemented, several portions

have a massive tower-like appearance, while different slender towers shoot

up above these. The octagon tower (built wholly of Colonsay granite) rises

to a height of 94, and the flag tower to 102 feet. There are in all 74

apartments in the castle, and a spacious corridor extends from end to end.

The furnishings are in a style of befitting splendour. *

5. Many of the people,

especially in the south of the Long Island, are Roman Catholics. Early

marriages are very frequent among them. Some of the rude-fashioned

instruments of husbandry, once common throughout the Highlands, retain their

hold here, and the ancient querns or handmills are in almost general use in

most of the secluded parts of Lews and Harris, and also in the southern

Barra Isles. The islanders of the northern part of Lews, with their long

matted and uncombed hair, which has never even been' restrained by hat or

bonnet from flowing as freely in the wind as their ponies' manes, and their

true Norwegian cast of countenance, form perfect living portraits of the

ancient Norsemen. The other inhabitants, chiefly of Celtic origin, combine

the characters of fishermen and field-labourers; they are distinguished by

acuteness no less than simplicity, and, though poor, they are honest and

hospitable.

Small packets, partly

supported by government, ply between each of the islands of North and South

Uist and Harris to Dun-vegan in Skye ; and from Stornoway to Poolewe, on the

coast of Ross-shire: thus keeping up a regular communication with the

mainland. A swift steamer, also, in the summer season, makes trips once

a-week from Glasgow to Stornoway, and once a fortnight in winter, driving a

thriving trade. She calls once a fortnight at Loch Inver.

In regard to internal means

of communication, we have here only to observe further, that Colonel Gordon,

in South Uist and Benbecula, has formed about fifty miles of road; that the

Countess of Dunmore, as acting for her son the Earl, still in his minority,

has made a fine road from Rodel, through Harris, to join those on Mr.

Matheson's estates; and that the Highland Destitution Fund has latterly been

to some extent employed, both in promoting industrious habits among the

peasantry, as fishermen and farmers, and in aiding in the construction of

roads and harbours. [At Bayhiravagh, in the mainland of Barra, there is a

small inn and two excellent roads, one of ten miles, along the west coast,

and the other of eight miles, passing through fine scenery on the east

coast. South Uist, where large tracts have recently been reclaimed from the

sea is now being skirted along the west side by a good road which, when

completed, will be twenty-four miles long, with a small inn at Poulachar, or

Kilbride, on Barra Sound, and another at Stonybridge, about twelve miles

farther north. Along the east coast, there is a range of bold lofty

mountains, deeply indented by arms of the sea, where there are several

anchorages with deep water, and in Lochboisdale a fine pier, accessible at

all times of tide. Benbicula separated from South Uist by a ford open from

six to eight hours each tide, and from North Uist by a rather intricate

ford, passable four to six hours each tide), is intersected by a fine new

road made by the proprietor, six miles long, with the little inn of

Craigorry at the south, and that of Gramisdale at the north end. In North

Uist there are two roads proceeding from Loch Maddy (where there is a good

inn), one of twelve miles, along the south coast to Cairinish, having no

resting place by the way; the other is twenty-nine miles long, divided by

the small but good inns of Grainetote, nine miles; Teighary, eight miles;

and Cairinish, twelve miles. At Tarbet, in Harris, there is a great inn.]

We conclude these general

remarks on the Long Island by submitting to our readers the following

beautiful description from the pen of, we believe, their native historian,

Professor William Macgillivray, now of Aberdeen, which we extract from his

very valuable account of the Outer Hebrides, published in the Edinburgh

Journal of Natural and Geographical Science for 1830, and which is fully

borne out by the recent statistical reports of the local clergyman.

6.. "The climate is subject

to great variations. It is, however, generally characterized by its great

dampness. In every part of the range iron is covered with rust in a few

days, and finer articles of wooden furniture, brought from foreign parts,

invariably swell and warp. Spring commences about the end of March, when the

first shoots of grass make their appearance in sheltered places, and the

Draba verna, Iuznunculus Ficaria, and Bellis perennis unfold their blossoms.

It is not until the end of May, however, that in the pasture-grounds the

green livery of summer has fairly superseded the gray and brown tints of the

withered herbage of winter. From the beginning of July to the end of August

is the season of summer, and October terminates the autumnal season. During

the spring easterly winds prevail, at first interrupted by blasts and gales

from other quarters, accompanied by rain or sleet, but ultimately becoming

more steady, and accompanied with a comparative dryness of the atmosphere,

occasioning the drifting of the sands to a great extent. Summer is sometimes

fine, but as frequently wet and boisterous, with southerly and westerly

winds. Frequently the wet weather continues with intervals until September,

from which period to the middle of October there is generally a continuance

of dry weather. After this, westerly gales commence, becoming more

boisterous as the season advances. It is, perhaps, singular, that while, in

general, little thunder is beard in summer, these winter gales should

frequently be accompanied by it. Dreadful tempests sometimes happen through

the winter, which often unroof the huts of the natives, destroy their boats,

and cover the shores with immense heaps of sea-weeds, shells, and drift

timber.

7. "After a continued gale of

westerly winds, the Atlantic rolls in its enormous billows upon the western

coasts, dashing them with inconceivable fury upon the headlands, and

scouring the sounds and creeks, which, from the number of shoals and sunk

rocks in them, often exhibit the magnificent spectacle of terrific ranges of

breakers extending for miles. Let any one who wishes to have some conception

of the sublime, station himself upon a headland of the west coast of Harris

during the violence of a winter tempest, and he will obtain it. The blast

howls among the grim and desolate rocks around him. Black clouds are seen

advancing from the west in fearful masses, pouring forth torrents of rain

and hail. A sudden flash illuminates the gloom, and is followed by the

deafening roar of the thunder, which gradually becomes fainter, until the

roar of the waves upon the, shore prevails over it. Meantime, far, as the

eye can reach, the ocean boils and heaves, presenting one wide-extended

field of foam, the spray from the summits of the billows sweeping along its

surface like drifted snow. No sign of life is to be seen, save when a gull,

labouring hard to bear itself up against the blast, hovers over head, or

shoots athwart the gloom like a meteor. Long ranges of giant waves rush in

succession towards the shores. The thunder of the shock echoes among the

crevices and caves; the spray mounts along the face of the cliffs to an

astonishing height ; the rocks shake to their summit, and the baffled wave

rolls back to meet its advancing successor. If one at this season ventures

by some slippery path to peep into the haunts of the cormorant and rock

pigeon, he finds them sitting huddled together in melancholy silence. For

whole days and nights they are sometimes doomed to feel the gnawings of

hunger, unable to make way against the storm; and often during the winter

they can only make a short daily excursion in quest of a precarious morsel

of food. In the mean time the natives are snugly seated around their blazing

peat-fires, amusing themselves with the tales and songs of other years, and

enjoying the domestic harmony which no people can enjoy with less

interruption than the Hebridean Celts.

"The sea-weeds cast ashore by

these storms are employed for manure. Sometimes in winter the shores are

seen strewn with logs, staves, and pieces of wrecks. These, however, have

hitherto been invariably appropriated by the lairds and factors to

themselves ; and the poor tenants, although enough of timber comes upon

their farms to furnish roofing for their huts, are obliged to make voyages

to the Sound of Mull, and various parts of the mainland, for the purpose of

obtaining at a high price the wood which they require. These logs are

chiefly of fir, pine, and mahogany. Hogsheads of rum, bales of cotton, and

bags of coffee, are sometimes also cast ashore. Several species of seeds

from the West Indies, together with a few foreign shells, as lanthin.a

communis and Spirula Peronii, are not unfrequent along the shores. Pumice

and slags also occur in small quantities.

8. "Scenes of surpassing

beauty, however, present themselves among these islands. What can be more

delightful than a midnight walk by moonlight along the lone sea-beach of

some secluded isle, the glassy sea sending from its surface a long stream of

dancing and dazzling light,—no sound to be heard save the small ripple of

the idle wavelet, or the scream of a seabird watching the fry that swarms

along the shores ! In the short nights of summer, the melancholy song of the

throstle has scarcely ceased on the hill-side when the merry carol of the

lark commences, and the plover and snipe sound their shrill pipe. Again, how

glorious is the scene which presents itself from the summit of one of the

loftier hills, when the great ocean is seen glowing with the last splendour

of the setting sun, and the lofty isles of St. Kilda rear their giant heads

amid the purple blaze on the extreme verge of the horizon."

9. It was on the little Island of Eriskay, at the south end of South Uist,

that Prince Charles Stuart first landed, on the 22d of July 1745, from the

small frigate of sixteen guns, the Doutelle, in which he sailed from

Belleisle, with the very limited suite who accompanied him on his chivalric

and excessively daring enterprise to recover the crown of Britain. his

retinue consisted of the Marquis of Tullihardine, otherwise called Duke of

Athole, Sir John Macdonald (a French officer), Mr. . neas Macdonald (a

banker in Paris), Mr. Strickland, Mr. Buchanan, Sir Thomas Sheridan, Mr.

O'Sullivan, and Mr. Kelly; to whom the precise Bishop Forbes adds, Mr.

Anthony Welch, the owner of the Doutelle. Along with this vessel, the

Elizabeth, a French ship of war of sixty-eight guns, had left port, as a

convoy ; but the latter vessel having, off the Lizard, engaged a British

ship of war, the Lyon, of fifty-eight guns, both were so disabled that the

Elizabeth had to be carried back to France ; while the little frigate made

its way alone for the north of Scotland. The adventurers were soon joined by

Mr. Alexander Macdonald of Boisdale, who assured the Prince that he had

miscalculated in reckoning on any assistance from Sir Alexander Macdonald of

Sleat, and the Laird of Macleod ; and his opinion turned out to be quite

correct. To Boisdale's remonstrances as to the foolhardiness of the

expedition, and the small chance of the clans mustering in any force, the

Prince replied :—"I am come home Sir; and I will entertain no notion at all

of returning to the place from whence I came for that I am persuaded my

faithful highlanders will stand by me." In a day or two the Doutelle sailed

for Loch-na-Gaul, sometimes called Loch-na-Naugb, between Arisaig and

Moidart, and the party landed on the 25th of July at Borradale, whence they

afterwards crossed that arm of the sea, and proceeded up Loch Shiel to

Glenfinnan, at the head of the loch, where the standard was unfurled. In

Loch-na-Gaul young Clanranald, with Mr. Macdonald of Kinloch-Moidart,

Macdonald of Keppoch, Mr. Hugh Macdonald, brother of Moidart, and Mr.

Macdonald, younger of Scothouse, came on board the Doutelle. The

communications from Sir Alexander Macdonald, Macleod of Macleod, and at

first from Lochiel (though Lochiel subsequently proceeded to Borradale),

were of such a nature that every individual, even the members of his suite,

importuned the Prince to return to France ; but he was firm in his

resolution, determined indeed, " having set his life upon a cast, to risk

the hazard of the die."

The ebb of his fortunes

brought the poor Prince back to the Long Island. And the best feature in his

deportment is, the magnanimity with which at this period he bore up under

his adverse lot, and the very trying privations to which he was subjected,

and the buoyancy of spirit with which he encountered the toils that hemmed

him round, gathering fresh elasticity from each recurring hair-breadth

escape, while wandering about a hunted fugitive, lie was secreted for

several days in the Cave of Corradale, on the east side of Benmore, in South

Uist.

Prince Charles effected his

escape from the Long Island to the Isle of Skye through the instrumentality

of the celebrated Flora Macdonald—he disguised as Betty Burke, the Irish

female attendant of Miss Macdonald ;—Miss Macdonald having procured

passports from Mr. Macdonald of Armadale, her stepfather, who commanded one

of the independent companies engaged in searching for the Prince. They were

accompanied by a Neil Mac Eachan, (father of Marshal Macdonald, Duke of

Tarrentum,) a sort of preceptor in Clanranald's family, who travelled as

Miss Macdonald's servant. |