|

The most prominent objects of

attraction in Skye. Skye Marble, 1.—Strathaird's Cave, 2.—Sail to Scavaig;

Bay of Scavaig and Loch Coruishk; Bruce's Encounter, 3.—Glen Sligachan; The

Saddle; Haunts of the Peer; comparison with Glencoe; The Cuchullins; Pass of

Ilartie Corrie, 4.—General Remarks on Skye; Kelp; The Caschrome; Farming;

Quern, 5.—Dwellings, 6.—Press of the Islanders; Hospitality; Women's

Apparel; Oruaments,7.—Population; Croft System; Poverty and recent distress;

Change in the Condition of the Highland peasantry in progress, 8.

1. The Spar cave, Scavaig,

and Coruishk, Glen Sligachan, and the Cuchullins, are the objects which

chiefly induce the stranger, except he be a geologist, to visit Skye. The

attention of travellcrs has hitherto been chiefly directed to the Spar Cave

and Coruishk, and Glen Sligachan is comparatively but little known ; though

it will be found equally worthy of observation. As all three can he

comprehended in one—a long day's excursion—we recommend tourists to arrange

their plans so as to combine this last scene with the others, as it can be

compared only to Glencoe; but may be said, like Coruishk, in some points to

surpass that celebrated spot in the very characters for which it is supposed

unrivalled in this country.

In proceeding to view these

objects from Armadale or Isle Oronsay, it is necessary to ride across to

Gillean (which can be done in about two hours), or any other point on the

opposite coast of Sleat, where a boat can always be procured. If we wish to

visit them from Broadford, we cross through Strath to Kilbride, a distance

of five miles, and there take boat. In Strath there are quarries of marble,

which were worked for a short time, but are now greatly neglected. The

marble is chiefly of a light grey colour, of which a very fine mantle-piece

is to be seen at Armadale; but some blocks are found as pure and

close-grained as the finest statuary marble. IIad Armadale Castle been built

of masses from these quarries, which it could have been at no great

additional expense, Skye might boast of one of the greatest architectural

curiosities in Scotland. It may be proper to add, that Strathaird's cave can

be approached from Sconser or Glen Sligachan, and that a boat can be

procured at some huts, about a mile to the west of the cave. Coming from

Kilbride, we pass the house of Mr. M`Allister of Strathaird.

2. Of the objects before us,

this cave first demands attention. It occurs on the north side of Loch

Slapin, on the west coast of Skye, and occupies the further extremity of a

Iong, straight, deep, and narrow excavation, which the sea has made in the

face of a high and perpendicular range of cliffs, such as are so common in

the Orkney Islands, and there technically termed Ghoes. As the sea often

dashes with violence into this narrow recess, the approach is, at times,

difficult. On first entering, the cave has the appearance of an ordinary

fissure, gradually widening as we advance; but we soon come to an inclined

plane of rock, covered with a beautiful white and hard calcareous deposit,

the walls on each side being also encrusted with a coating of the same

substance. The inclination of this plane is pretty steep; and the surface,

from its glistening appearance, seems so slippery, that one hesitates before

attempting to climb it. It is sufficiently rough and granular, however, to

admit of safe footing; and having surmounted this little acclivity, we are

ushered into a lofty chamber, lined from top to bottom by, and paved with,

translucent and white stalactite. The surface of the floor is unequal, and

the further extremity of the gallery is occupied by a deep and clear well.

On the inner side of this well the rock has assumed a fanciful and gigantic

resemblance to a human figure, which, in its robes of pure white, may be

regarded as the guardian genius of this beauteous sparry grotto. Not many

years ago, large stalactites hung from the roof, and there were even some

pillars extending from the floor to the ceiling; these have, however, been

unfortunately destroyed, and the cave has not altogether recovered from the

effects of the injudicious introduction of tar torches, instead of candles,

which are generally used.

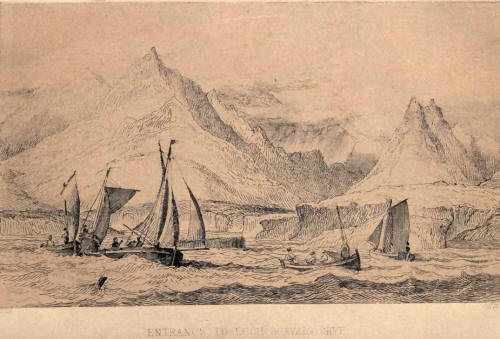

3. From Strathaird to

Coruishk is a long sail round the projecting headland of Aird. In the

western horizon are seen the islands of Rum, Muck, and Eig, and, more near,

a small island called Soa.

The Bay of Scavaig, into

which Loch Coruishk discharges itself, is a scene of almost unexampled

grandeur; and, being less confined than the latter, presents an interesting

difference of character. It is flanked by stupendous shivered mountains of

bare rock, which shoot up abruptly from the bosom of the sea. They are of a

singularly dark and metallic aspect, being composed of the mineral called

hyperstein. On the left are three shattered peaks :—Garbshen, or "the

shouting-mountain," Scuir-nan-Eig, "the notched peak," and Scuir Dhu, "the

black peak;" and on the opposite side is a similar and very high hill,

called Scuir-nan-Stree, "the hill of dispute," or "the debateablo land." A

little island at the base of Scuir-nan-Stree is styled Eilan-nan-Lice, "the

island of the slippery step," from a dangerous pass in the face of the rock,

which makes it imprudent in a stranger to visit these scenes by land.

The river which falls into

Scavaig Bay is not above 250 yards in length. Ascending its rocky channel,

we suddenly find ourselves on the margin of a fresh-water lake. Loch

Coruishk is a narrow lake, about two miles in length, from the edge of

which, on all sides, rise naked, lofty, and precipitous mountains, of the

same dark, barren, hyperstein rock, and furrowed with numerous hollows, or

corries. A few rocky islets, partially covered with dwarf mountain-ash and

long grass, afford a secure nestling-place to flocks of sea-gulls, which are

the only living creatures to be seen, unless a stray goat be descried among

the recesses of this wilderness, where they are

become as wild and

uncontrolled as on Robinson Crusoe's island of Juan Fernandez. An inclined,

rugged, and irregular platform of sharp-surfaced naked rock, with detached

rocky masses, and a stunted sward interspersed, immediately encircles the

waters of the lake, and enhances its sterile desolation, except at the upper

extremity, where it gives place to a grassy plain of refreshing verdure,

where the red deer oft times resort.

We are now treading on

classic ground. It was here the Bruce encountered Cormac Doil; and the

scenes around have been celebrated by the gifted pen of our great poet and

novelist. Perhaps few of his vivid descriptive passages are more felicitous

than the following:

"The wildest glen, but this,

can show

Some touch of Nature's genial glow;

On high Benmore green mosses grow,

And heathbells bud in deep Glencroe,

And copse on Cruchan-Ben;

But here—above, around, below,

On mountain or in glen,

Nor tree, nor shrub, nor pant, nor flower,

Nor aught of vegetative power,

The weary eye may ken.

For all is rock at random thrown;

Black waves, bare rocks, and banks of stone,

As if were here denied

The Summer sun, the Spring's sweet dew,

That clothe with many a varied hue

The bleakest mountain side."

These lines by no means

exaggerate the barren grandeur of Coruishk; indeed, it is impossible to do

justice to this rude scene. The grisly acclivities rise so abruptly, and

encompass so closely the dark and narrow lake, that, but for the reflection

of the sunbeam, its shores might almost be said to be veiled in eternal

night; while, frequently, dense vapours, curling round the circling rocks,

bestow an indistinctness of form and outline the eye of Superstition might

quail to contemplate. The remoteness of this solitude, and the gloomy

silence that reigns, and the savage forms that surround it, impress a solemn

seriousness on the mind. Few, indeed, finding themselves on the shores of

Coruishk, can, with reason, refuse to exclaim with the Bruce

A scene so wild, so rude as

this,

Yet so sublime in barrenness,

Ne'er did my wandering footsteps press,

Where'er I happ'd to roam."

- Lord of the Isles, canto iii.

4. Glen Sligachan terminates

in a bay adjoining Scavaig to the south, whence it stretches across the

Island to Loch Sligachan. A farm-house at the west end of the glen, called

Camusunary, (Mr. Mac-Rae), is the only dwelling-place to be seen along the

shores of this remote region, where its white walls, its freestone

window-lintels, its slates, and green door, are viewed with the agreeable

surprise one feels at unexpectedly meeting old friends. Mr. Mac-Rae's boat

is, of course, the only one to be had; and, as his shepherds are seldom at

hand to man her, it is imprudent in the traveller to pass through Glen

Sligachan on his way to Coruishk. He should proceed to it by boat, from

Sleat or Kilbride, and reserve Glen Sligachan for the latter part of his

day's excursion. We would warn him, however, that he will take three or four

hours to walk to the inn at the other end of the glen, (eight miles

distant). The bottom of the valley is very uneven, and quite pathless,

excepting the track which has been worn by the few ponies which pass the

way: the burns, also, are numerous, and after rain swell very suddenly, and

sometimes to a considerable depth.

The extreme breadth of the

valley, between the precipitous parts of the mountains, may be about a mile;

in some places they approach within a few hundred yards of each other. A

river runs out at either end, fed by numerous torrents, which channel the

sides of the mountains. The western one, and the river Scavaig, abound with

salmon. On either side of the rivers is a tract of broken, sloping, rocky

moorland, out of which the mountains tower up on very abrupt acclivities.

They are chiefly composed of the same black-looking hyperstein rock which

surrounds Coruishk; and are almost equally destitute of vegetation, except

some of the declivities, which are tinted with patches of verdure. Near

Camusunary are two small lakes, Loch-nan-Aanan, "the lake of fords," and

Loch-na-Creich, "the lake of the wooded valley," a name certainly not

applicable to its present condition, but which, with the appearance of some

stumps of trees among the moss, prove this, like many other parts of the

Highlands, to have been once covered with wood. The first mountain on the

west, next Camusunary, is Scuir-nanStree, already noticed as dividing the

glen from Coruishk; and opposite it is Blaven, (Blath Rhein), a long,

sharply-ridged, and pointed mountain, not properly one of the Cuchullin

group, but of the same distinctive character. One ascent of this latter

mountain is peculiarly hazardous, as, at a part called "The Saddle," the top

of the ridge is for two yards scarcely above a foot in breadth. We have met

with shepherds who have crossed this dangerous pass ; to them the steepest

hills in the neighbourhood are accessible, but they declared some of the

pinnacles to be so needle-peaked, that a man could hardly venture to stand

on the top of one of them.

The next mountain to Blaven,

is Ruadhstach; and the lofty and perpendicular one beyond it is Marscodh.

Both are favou- rite haunts of the red deer, who may generally be descried

browsing about the summit. Among the singular assemblage of pinnacles on the

west side, above Sligachan, are Basader and Scuir-nan-gillean, the highest

of that extensive and peculiar series of mountains included in the general

term, Cuchullin, several of which, with Blaven, and others on the south of

the glen, exceed 3200 feet in altitude. On the rough sides of Glen Sligachan

are reared large flocks of goats.

The mountains of this wild

glen are considerably higher, and not less savage than those of Glencoe. The

two contrast in that the gigantic barriers of Glencoe are more

perpendicular, and hem in the glen more closely—meeting the eye at times,

especially in the descent from King's-house, in close proximity, challenging

emotion by their impassable and threatening front; while in Glen Sligachan,

the character is that of a vast display of dark, naked rock, which, if it

lose in impressiveness, from being less absolutely precipitous, and also in

being further removed from the spectator, compensates by comprehending the

full expanse of the mountain acclivities, from base to summit, in continuous

sheeted masses of naked sterility, on a scale rarely to be witnessed, and

assuming in the mountain outlines very marked, and even fantastic features:

The scenery of the Cuchullins is rendered the more effective from the

mountains springing almost from the sea level : thus presenting elevations

as striking as inland mountain countries of much greater actual altitude. In

traversing the solitudes, too, we feel a constant, and almost painful

consciousness, that no other form of mortal mould exists within their desert

precincts. A solemn silence generally prevails, but is often and suddenly

interrupted by the strife of the elements. The streams become quickly

swollen, rendering the progress of the wayfaring stranger not it little

hazardous; while fierce and fitful gusts issue from the bosom of the

Cuchullins. The heaven-kissing peaks of this strange group never fail to

attract a portion of the vapours, which, rising from the Atlantic, are

constantly floating eastward to water the continent of Europe; and fancy is

kept on the stretch, to find resemblances for the quick succession of

fantastic appearances which the spirits of the air are working on the

weather-beaten brow of these hills of song.

Instead of being conveyed to

Camusunary, and proceeding from thence along Glen Sligachan, the latter may

be reached across a wild pass, called Hartie Corrie, which traverses the

Cuchullins, and gives the advantage of, in going, a grand mountain ravine,

while it leads into Glen Sligachan at a point where the most imposing view

is presented of the Cuchullins. Let not the view-hunter, however, select

this mode of approach to Coruishk. The fatigue of the walk helps to blunt

the appreciation of its characteristics, and the previous familiarity with

scenes of gloomy grandeur, tends to, perhaps, a degree of disappointment of

the expectations entertained. The first impression, indeed, looking down

upon Coruishk from the high hill which separates it from Hartie Corrie, is

perhaps one rather of savage beauty, though unquestionably to adopt a bold

image—"beauty reposing in the lap of terror."

5. In concluding our remarks

on Skye, we may observe, that black cattle, sheep, and kelp form its chief

riches. For the sale of the former, two or three markets are held annually

at Portree. Kelp is formed by burning sea-ware, previously dried in the sun,

in small circular and oblong pits, attended by men to rake the crackling

ingredients. The smoke of these pits spreads during the summer months in

dense volumes round the shores, and diffuses a disagreeable pungent odour.

This alkaline substance, as is well known, is chiefly used in the

manufacture of glass. The best kind is made from the seaweed cut from the

rock, which is generally done every third year; that made from the

drift-ware is naturally more impure. During the late war, kelp yielded above

£20 per ton. Now, from the introduction of Spanish barilla, and other

causes, the price scarcely averages a fourth of that sum. It may be

conceived that it is, or at least lately was, a chief source of the revenue

of the west coast and Orkney proprietors, from the circumstance of

Clanranald's estate having some years produced 1500 tons of this article. We

trust that the alleged valuable properties of the recently discovered

alkali, called kelpina, may restore to kelp, as some anticipate, a portion

of its former value. The climate of this island is exceedingly damp: the

farmers, in consequence, are all provided with wattled barns, having lateral

openings, closed only by twigs and boughs of trees, where they are able to

dry part at least of their scanty crops in the most rainy seasons. In

husbandry, the caschrome, or ancient crooked spade, is a good deal used by

the poor; it is a clumsy substitute for a plough, with which an active man

will sometimes prepare about a fourth of an acre in a day ; and is certainly

of advantage in the cultivation of their miserable crofts, which are

frequently altogether scarcely equal in value to the purchase price of a

plough. The casclarome is formed either of a stout obtusely angled knee of

wood, or two pieces bound together with iron: the upper limb or handle is

four or five feet long; the lower about two and a half feet, and shod at the

point with a sharp flat piece of iron, which is driven into the soil by

means of a lateral wooden peg projecting from the angle, on which the right

foot acts. The rest of the farming of the cottars is of a piece with this.

Harrowing is performed with a rake, or light harrow with wooden teeth, drawn

by a man or woman—for the women put their hands to many a piece of drudgery

not allotted to them elsewhere—or this implement is sometimes drawn by a

horse, to whose tail it is attached by a straw rope. The people of all

classes are extremely partial to drying their grain in iron pots over the

fire, before being converted into meal; and till a recent period the whole

sheaf was passed through the fire to the entire sacrifice of the straw. No

rotation of crops is observed except from potatoes to oats, and from oats to

potatoes; and a series of oat crops is often taken till the land is run out,

when it is allowed to rest for another term of years useless under weeds.

Among the larger tacksmen regular rotation and many improvements are

observed, but the dampness of the climate, notwithstanding the accompanying

mildness of temperature, is unfavourable to agriculture. The Cheviot sheep

are now common.

The quern, or handmill, is to

be found in some of the remote districts of Skye. It consists of two flat

stones, about twenty inches in diameter, selected for their hardness and

grittiness. Across the central hole in the upper stone, is a piece of wood,

with a small tapering hollow, which fits a wooden pivot on the lower stone.

Placing the finger, or a stick, in a hole sunk for that purpose, close to

the exterior edge of the upper stone, it is with the greatest facility made

to revolve with the desired velocity; and the whole machine being placed on

a sheet, or sheepskin, the grain gradually poured in at the hole in the

upper stone, is speedily ground into meal, which falls out at the

circumference between the two stones. This seems to have been the first

grinding instrument in all countries, and is evidently that alluded to in

Scripture:—"Two women shall be grinding at the mill" (that is, one feeding

and the other turning it), "the one shall be taken, and the other left."

6. The dwellings of the

poorer Hebrideans generally are extremely mean and comfortless. They consist

of three apartments, of which the first is appropriated to the cattle, and

the access to the whole is through the byre, the door being at the end; and

this byre being only cleaned out twice a-year, the consequent filth requires

no comment. The apartments are separated by low partitions of stone, board,

or wattle-work. In the centre is the sitting-room—the fireplace in the

middle of the floor, and the smoke pervading all parts, there being only an

outlet in the roof. A rough table, one or two stools, an arm-chair of

plaited straw, reserved for the exclusive use of the goodwife, occasionally

a rude sofa-bench for four or five persons, and a chair or two, but as

frequently mere stones, covered with turf, for seats; and in the innermost,

the sleeping-apartment, a couple of bedsteads, filled with heather, ferns,

or straw, comprise the bulk of the furniture. The walls are of stone,

generally double, the vacancy being crammed with earth. They are at times,

particularly in the Long Island, seven or eight feet thick, and form a ledge

on the outside, on which a couple of sheep can graze abreast, or two persons

might walk round the roof, which is supported by a few rough undressed

couples. A single small window, often without glass, is all there is for

light. The soot-saturated thatch is commonly removed every year, to serve as

manure for the potatoes. The fare of the peasantry is chiefly potatoes, with

fish, shell-fish, milk, and a little meal, but little or no animal food.

7. The dress of the Islesmen

has always differed from that of the mainland Highlanders. The kilt, which,

no doubt, is now falling into general disuse, is not to be met with in Skye,

and it seems never to have been worn here. At present, the ordinary fashion

of short coats and trousers of coarse cloth universally prevails. From their

frequent boating, one would expect to find the dress of the Skyemen adapted

to the seafaring life; but even a cut-away jacket is seldom to be seen. The

people have none of those distinctive marks which at once betray the

occupation of those curious tribes—the fishermen of the east coasts. Indeed,

except during the herring season, these islanders seldom trouble their heads

about fishing, unless it be to catch a few rock-cod, lythes, and cuddies,

for the use of their families; and even this duty ordinarily devolves on the

younger urchins. Various efforts have been made to extend the deep-sea

fishing, but, unless under the immediate stimulus of individual enter-prize,

it does not seem to make sensible progress—except in the Lewis, where the

quantity of cod and ling taken is now very considerable—while the more

uncertain fruits, and more fitful labour, of the herring fishery finds

general favour in all parts of the Highlands and Islands. It is strange that

constant exposure to the sea-breeze does not teach the general use, in the

Isles, of the small felt bonnet, or some substitute for the common hat,

which is generally worn. The west coast Highlanders or Islesmen, when they

make their appearance in any of the towns of the east coast, may almost be

detected by their hats, from the picturesque shapelessness and amphibious

consistency which their head-gear speedily acquires from steeping in the

Atlantic mists. The Orkney boatmen, who are more constantly on the water,

understand these things better, and by their comfortable southwesters—a

glazed, or leathern skull-cap, shaped like that of an Edinburgh carter, with

a broad flap hanging down behind to protect the neck—give proof of their

experienced wisdom. Such a thing as a straw bonnet is rarely to be found

among all the female peasantry of Skye, or of the Islands in general. The

lasses go bareheaded, trusting to the attraction of the emblematic snood;

matrons bedizen themselves with the varieties of the venerable and simple

mutch, curtch, and toy; and the clothing of the female population of Skye is

hence generally coarse and mean in the extreme. No comfortable cloak of "guid

blue cloath," which many of the east coast Highland wives have added to

their wardrobes, is to be seen. The old women throw a dirty breachdam,

resembling a blanket, over their shoulders: the others have seldom anything

to vary their simple gowns of dark blue or brown stuff.

An air of squalid penury,

too, soon settles about them; and in middle age their prematurely-pinched,

care and penury-worn features, are far from engaging ! Kindly feelings and

affections, however, live under this unpromising exterior. The people of

Skye and the adjacent islands, and west coast of the adjoining counties, are

of short stature, firmly knit, active, and more mercurial than the central

Highlanders. Such generalizing observations must of course not be strictly

interpreted. The gentry of these parts are wonderfully numerous. They are

exceedingly hospitable; and the Southron will, perhaps, be astonished to

find in their houses all the comforts and elegancies of life. The ladies are

characterized, for the most part, by fair complexions, tall, slender forms,

and blue eyes, indicative of their northern origin. The peasant women are

remarkable for their industry, at least in spinning; for they are always to

be seen with the old rock and distaff in their hands, whether walking or

seated by their hearths, or at their cottage doors. A brooch of pewter,

brass, copper, or silver, used by the old women to fasten their

blanket-plaids in front, is almost the only ornament indulged in. It is

often preserved with much care, and handed down from mother to daughter as a

valuable family relic.

8. The population, as of the

other Hebrides, is very redundant, owing to the system of small crofts,

which, becoming subdivided, are too small for the support of a family—a

pernicious system, to which the kindly feelings and the cupidity of

landlords and tacksmen have been alike tempted: for, while it is painful to

the most ordinary sensibility to dispossess the people, the high nominal

rents increasing according to the minuteness of subdivision, occasionally

may have subserved a purpose, and thus led to the same result as the

disinterested and benevolent feelings which, in general, prompt to the

perpetuation of the mistaken system. Now the pressure of the recent Poor

Laws has alarmed Highland proprietors, and, of late, precipitated more

frequent occasional summary ejectments, and compulsory emigration.

Unfortunately it too often happens that their own embarrassed or

straightened circumstances stand in the way of those gradual changes which

humanity and sound policy dictate. The failure of the potatoe crop,

occasioning an excessive degree of distress, where, as in the Highlands and

Islands, it had been a staple source of sustenance, has contributed to

hasten on a general change in the condition of the Highland peasantry. Much

difference of opinion prevails as to the best system for their permanent

welfare, as to size of croft and other details; and public attention is kept

so much alive on the subject, that though many of the poor Highlanders must

needs be subjected to many a bitter pang in their present transition state;

and no people endure the ills of life, and the pinching poverty of their

lot, with so much of unrepining and quiet endurance, it cannot be doubted

that eventual and permanent amelioration must be the result; and it is to be

hoped that all persons immediately concerned will act under an increasing

sense of responsibility towards those committed by providence in

subordination to them. The young men in Skye and other islands go to the

south in summer to seek work, and return in winter: the young women for a

shorter time in harvest. A large portion of the middle-aged resort to the

herring fishing on the cast coast, during June, July, and August—a migratory

character which is not favourable to morals or religious principle. |