|

DIVISION I. SKYE.—FROM

ARMADALE, KYLE BHEA, AND KYLE AKIN, TO DUNVEGAN AND DUNTULM.

General Description of Skye,

1.—Isles of Rum, Eig, and Muck; Tale connected with Cave in Eig, 2.—Armadale

Castle; Isle Oronsay; Isle Oronsay to Broadford, 3.—Kyle Rhea, 4.—Kyle Akin;

Castle Maoil, 5.—Broadford to Scouser and Portree, 6. Portree, 7.—East Coast

of Trotternish; Caves; Store, 8.—Portree to Dunvegan, 9 —Village of Stein,

10.—Dunvegn Castle; Antique Relics at Dunvegan, 11.—Piper's College;

MacCrimmons of Borreraig, 12.—Clach Modha, or The Manners' Stone at

Galtrigil; Phenomenon at Dunvegan Head; Glendale; Vaterstein, 13.—Lady

Grande, 14.—Dunvegan to Sligachan; Lochs Struan, Bracadale, and Herport;

Sepulchral Cairns; Episcopal Chapel; Round Tower, 15.—Talisker, 16.

Trotternish; Bay of Uig; Duntulm Castle, 17.—Quirning, 18.—Prince Charles'

Wanderings, 19.

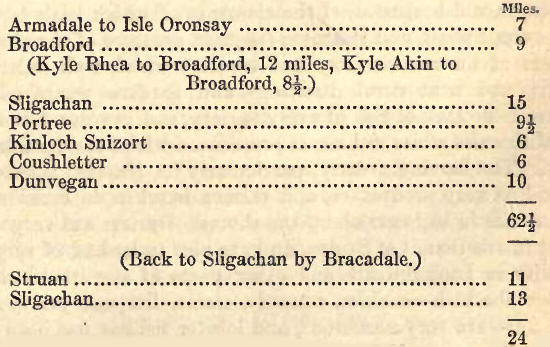

1. SKYE forms no

inconsiderable part of the county of Inverness, and is the largest of the

Western Islands. In the ancient language of the country, says Martin, it is

called Ealan Skianach, or the Winged Island, "because the two opposite

northern promontories (Vaternish lying north-west, and Trotternish

northeast) resemble two wings." Though its extreme length is upwards of

fifty miles, with a breadth varying from ten to twenty-five, it is so much

indented by arms of the sea, that it is said there is not a spot in the

island at a greater distance from the sea than three and a half miles. It

has thus as rugged an outline as any of the incise-serrated fuci with which

its shores abound. The predominating character of the island is perhaps that

of a great mountainous moorland; but it contains extensive ranges of

excellent grazing, many green hills, and in some districts a considerable

extent of fertile arable land. The mountains stand rather in groups than

ranges, and are no less striking and unusual, than diversified in their

character and outline. The most prominent and imposing of these are about

the middle of the island, and are visible from almost every part of it. The

coasts, especially on the west and north-east sides, are rocky, bold, and

varied in outline, sometimes rugged and precipitous, and again rising by

gentle slopes into irregular terraces, diversified by projecting crags, deep

hollows, and lofty pinnacles of rock. Few countries present more of the

grand and sublime in scenery than this island generally affords; and with

its magnificent and varied sky lines, its intermediate elevations and

undulation of surface, and the never-failing presence of the sea in its

numerous bays, lochs, and creeks, it has much of the picturesque and

beautiful, of the elements of which little is wanting except wood, and the

more frequent presence of the cheering proofs of human industry and comfort

which well cultivated fields, and neat rural dwellings and gardens would

supply. There is no lack of fish of every variety, and in some favourable

localities the white fishing is prosecuted with considerable success. The

herring fishery, particularly on the east side of the island, is very

productive, and salmon is taken in considerable quantities in bag nets along

the shores. Oysters are very abundant in the Sound of Scalpa, and are also

to be had of very fine quality in Loch Snizort, and other parts of the

island shores. Other shellfish—cockles, mussels, clams, limpets,

periwinkles, &c. &c.—are very numerous, and lobster fishing has been pursued

successfully on the west side of Skye, particularly at the island of Soa.

There is an extensive and well-stocked deer forest at the head of Loch

Ainort. Roe deer are numerous in the woods of Armadale, and grouse, black

game, and partridges afford good sport all over the island. Pheasants have

been successfully introduced at Dunvegan, and at Armadale hares have now

become numerous, though former attempts to introduce them into Skye, where

they are not indigenous, had been unsuccessful. Until within the last three

or four years no hares Were to be found in Skye, except in the small island

of Paffa, near Broadford.

The greatest assemblage of

mountains occurs on the southern border of the central portion of the

island, called Minginish. Here the Cuchullins, so often mentioned in the

songs of Ossian, exhibit a series of lofty and splintered peaks which meet

the eye in every direction, and all the mountains in this quarter are peaked

or conical, and present a very unusual appearance. An excellent road, though

unavoidably hilly, has been opened from the south, along the east coast of

Skye as far as Portree. Here it cuts across the country to the head of Loch

Snizort, where it divides into two branches: one leading along the west

coast of Trotternish past the bay of Uig; the other conducting to Stein and

Dunvegan, whence it has been continued by Bracadale, on the west coast, back

to the head of Loch Sligachan.

2. Of the roads leading from

the Three Ferries betwixt Skye and the mainland, we will commence with the

most southerly, that from Armadale through Sleat. This road corresponds with

the one from Fort-William to Arisaig. In crossing the ferry, or now by the

steamer which calls off Arisaig, and has superseded the ferry-boat, we enjoy

a very extensive view, commanding the whole eastern shore of Sleat, the

opposite coast from Glenelg to the point of Ardnamurchan, the hills of

Applecross in the distant north-eastern horizon, and to the west the islands

of Rum, Eig, and Muck. These islands are easily visited from Armadale or

Arisaig. The produce of them all, as of most of the Western Islands,

consists principally of sheep and black cattle.

Eig is distinguished by a

peculiarly shaped hill—the Scuir of Eig— terminating in a lofty pillar-like

peak, surrounded by high and perpendicular precipices. In the south of the

island is a large cave, in which the whole of the inhabitants were at one

time smoked to death by the laird of Macleod, in revenge of an insult

offered to some of his people. The inhabitants of the island having taken

refuge in this cave, the entrance of which is not easily found, the Macleods,

after an ineffectual search, concluding that the natives had all fled, were

about to return to their boats, when they espied a man, whom, as there was

snow on the ground, they traced to this his own and his fellow-islanders'

place of retreat. Macleod caused a fire to be lighted at the mouth of the

cavern, and all within were suffocated. The floor is to this day strewed

with fragments of skeletons, evidences of the truth of the horrible tale.

Rum is a bleak mountainous

country: its only remarkable productions are its heliotropes, or

bloodstones, and its trap rocks. Both Rum and Fig are approachable on the

east side only; the western coast being very precipitous, with a strong

swell always rolling in from the Atlantic.

Rhum

Mesolithic and Later Sites at Kinloch, Excavations 1984–86 by Caroline R

Wickham-Jones (pdf)

3. But to return to Skye.

Armadale Castle, on the south coast of Sleat, the seat of Lord Macdonald, is

a modern Gothic building; a third part only of the original plan of which

has been completed. The finished portion is a simple broad oblong, with an

octagonal solid tower rising on each side of the doorway. It overlooks the

sea, and commands an extensive view of the bold rocky ranges of hills

opposite, in Glenelg, Knoidart, Morar, and Arisaig, with the openings of

Loch burn and Loch Nevish. The plantations about the castle are extensive,

and it is also surrounded by some fine old trees. Its chief embellishment is

a large staircase window of painted glass, representing Somerled of the

Isles, the founder of the family, (who flourished in the twelfth century),

in full Highland costume, armed with sword, battle-axe, and targe.

Lord Macdonald's estates in

the Western Islands are so extensive, and so much indented by the sea, that

the coast line of his possessions is, on a rough calculation, supposed to

exceed 900 miles, and the number of people on the property to be about

16,000.

There is no accommodation for

travellers near Armadale, except a small public-house, a mile to the south

of the castle, where a pedestrian might contrive to pass a night. The

parliamentary road terminates here; but a district road communicates with

the point of Sleat.

In proceeding to Broadford,

two miles from Armadale, we pass the church and manse of Sleat, and, at a

like interval further on, the house of Knock; beside which are the ruins of

an old square keep. Three miles beyond Knock, we come to Isle Oronsay, where

there is an admirable natural harbour, now regularly visited by the Glasgow

steam-boats, which proceed to Portree ; a constant communication being thus

kept up between Skye and the south of Scotland. A small steam-boat inn is

also to be found at Isle Oronsay.

The distance hence to

Broadford is nine miles. The road strikes off from Kinloch, a small

farm-house at the head of Loch-iii-Daal, across the island, and joins the

Kyle Rhea road, within about a mile and a half of Broadford. The east coast

of Sleat from its southern position and excellent exposure, may perhaps be

called the most genial portion of Skye, but in fertility it is far surpassed

by Waternish and the north end of Trotternish, in both of which districts

there is much arable land of very excellent quality. But for the most part

our course through Skye lies through moorland, almost uninterruptedly bleak

and dreary, with no features akin to the rich and sylvan beauties of other

parts of the country. But Skye is not, therefore, devoid of interest: on the

contrary, in the novelty, wildness, and grandeur of some of its scenes, it

has as much to boast of as it is deficient in fertility and the softer

graces of landscape.

4. We proceed now to conduct

the reader into the centre of the island by way of Kyle Rhea and Kyle Akin.

The extremities of the strait between Skye and the mainland have been called

Kyle Rhea, "King's Kyle," and Kyle Akin or Haken, in commemoration of

incidents which occurred on the expedition of Hato, king of Norway, in the

year 1263. The ferry at Kyle Rhea is about a third of a mile in breadth, and

the tide runs with great velocity through the narrow channel; but the

ferry-boats are good, and the crews attentive. On either side stands a

solitary public-house, affording pretty good accommodation. From the shores

of Skye a very fine view is obtained of Glenelg, with the old barracks of

Bernera, and an extended line of coast. The whitewashed houses observable

near the barracks, are part of a village which the late Mr. Bruce of Glenelg

projected, solely for retired officers; where they might at once enjoy "otium

cum dignitate," and the society of old comrades and brothers in arms.

The stage from Kyle Rhea to

Broadford, a distance of twelve miles, is extremely hilly and uninteresting,

if we except the view which, in descending, is presented of the celebrated

Cuchullins, the hills of Glamack, and the table-shaped summit of Duncaan,

which surmounts the island of Rasay. The road is joined by the Kyle Akin

road, four miles and a quarter from that place, and rather more than four

from Broadford.

5. At Kyle Akin, the late

Lord Macdonald contemplated the establishment of a considerable seaport

town, and had imposing and splendid plans prepared for it; but the scheme

proved quite abortive. The scale of houses fixed upon—two storeys, with

attics—was beyond the means of the people, and no man of capital was got to

settle in the place; and hence Kyle Akin has never attained a greater status

than what about a score of respectable-looking houses can lay claim to; but

it possesses a good inn. Close to the village are the ruins of an old square

keep, called Castle Muel, or Maoil, the walls of which are of a remarkable

thickness. It is said to have been built by the daughter of a Norwegian

king, married to a Mackinnon or Macdonald, for the purpose of levying an

impost on all vessels passing the kyles, excepting, it is said, those of her

own country. For the more certain exaction of this duty, she is reported to

have caused a strong chain to be stretched across from shore to shore; and

the spot in the rocks to which the concluding links were attached is still

pointed out.

6. The village of Broadford,

which is a tolerable one, consists of only a few houses and the inn. The

charges, as in most part of Skye, are moderate.

Sligachan, at the head of

Loch Sligachan, fifteen miles distant, is now the first stage from Broadford.

Along the Sound of Scalpa the slope of the hill is clad with hazel and birch

bushes, among which several little streams are seen precipitating their

waters in foamy cascades; and in the autumn months a considerable number of

herring smacks are generally to be seen at anchor in the Sound. From hence

the road leads along the side of Loch Ainort; and, crossing at its head a

small river of the same name, ascends the lower slope of the lofty and

precipitous mountains of Glamack. The road to Portree makes a circuit round

the head of Loch Sligachan, where the assemblage of mountains at the

entrance of Glen Sligachan is not a little striking and remarkable. On one

hand the Cuchullin mountains shoot their naked rocky peaks into the clouds ;

on the other, a series of dome-shaped hills rises from the plain, the

rounded tops of which, washed bare by the incessant rains, expose to view an

uncommonly red, gravelly surface, variegated only with occasional stripes of

green sod. In a small fresh-water loch above the commodious and well kept

inn of Sligachan, is found that very rare plant the Eriocaulon septangulare.

7. The rest of the way to

Portree (the king's port or haven, where James V. is said to have lain for

some time at anchor on his voyage round Scotland) is an uninteresting

moorland, until we approach within three or four miles of the village, to

which the road leads through the pastoral valley of Glenvarigil, and along

the shores of Loch Portree. In approaching the village, the eye is caught by

the bold cliff of the mountain Storr (2100 feet high) and the lofty

pinnacles of rock, which, springing from the bosom of the hill at a great

elevation, arise steeple like in front of the precipice. Close to the

village, the well-enclosed and sheltered fields and thriving plantations, in

the midst of which the residence of Lord Macdonald's commissioner is

situated, afford a most agreeable and refreshing contrast to the waste and

dreary tract through which the tourist has proceeded since leaving Sligachan.

The village is prettily situated on the north side of the fine bay of

Portree, which, running inland upwards of two miles, affords a safe and

spacious harbour, the entrance to which is marked by bold rocky headlands,

while in front of the bay, and at a distance of about four miles, extends

the Island of Rasay. The village boasts of two branch banks (National and

North of Scotland), the parish church, a court-house, a recently erected

prison, and a comfortable and well-conducted inn. From the centre of the

village there juts into the bay a wooded and craggy promontory, to which the

rather cockneyish name of Fancy Hill has been given. On its summit a neat

octagonal tower has been built, and walks have been very tastefully formed

along its sides, from which delightful views of the harbour and the

surrounding country are obtained. In spring and early summer, when the hill

is adorned with a profusion of wild flowers, and its woods are instinct with

the movements and voices of birds (it is a favourite resort of the cuckoo),

a vacant hour cannot well be more pleasantly spent than in a lounge on Fancy

Hill. On the top of the hill there is pointed out the grave of a man who was

executed there for murder and robbery about ninety or hundred years ago. His

victim was a pedlar, or, in the language of the country, a travelling

merchant. He was stabbed with a dirk, and then thrown over a rock on the

wild coast of the east side of Trotternish. The murderer escaped

apprehension, and wandered through the country for many months, but was at

last taken by a gentleman in the neighbourhood of Portree, and hanged on

this hill. It is a singular circumstance, that during this wretched

fugitive's wanderings he composed a song, which is still remembered, in

which the circumstances of the murder are minutely described.

There is direct steam

communication with Glasgow (Dunoon Castle and Mary Jane) twice a-week during

summer and autumn, and weekly during the rest of the year. Portree has

increased considerably since the publication of the last edition of this

work. Two or three neat villas have arisen in the vicinity; a handsome Free

Church is being erected, and a woollen manufactory, the machinery driven by

water power, has been established by Mr. Hogg, under the auspices of the

Highland Destitution Relief Board. From this establishment the women of Skye

receive unlimited employment in knitting, at a rate of remuneration equal to

that paid for similar work in Aberdeenshire ; from twenty to thirty persons

will be employed in and about the mill itself; and there is every reason to

anticipate that the establishment will prove remunerative to its intelligent

and enterprising proprietor, and contribute essentially to the welfare of

the district.

8. The cliffs towards the

mouth of the bay are remarkably fine, and form the commencement of a

magnificent range of coast scenery, which stretches along the east side of

Trotternish to the Point of Aird. The first portion to Ru-na-bradden

consists of high precipitous and continuous cliffs, occasionally broken into

successive terraces characteristic of the trap rocks of which they are

formed, and presenting no indentations or landing-places. About the centre

rises the Storr, a lofty mountain, the sea side of which is quite

perpendicular, especially towards the summit, and affords some singular

appearances, having poised on its lower acclivity several detached and

sharply pinnacled masses of rock of great height. One of these is strikingly

like the monument to Sir Walter Scott, in Princes Street, Edinburgh ; and,

singularly enough, there is a projecting part of the same rock, which, when

viewed from a certain point, strongly resembles the bust of the Great

Novelist. The tourist ought by no means to omit a visit to Storr, and he

will find himself amply repaid, not only by the solitary grandeur of the

scene itself, with its Crags, knolls, and mounds confusedly hurled, The

fragments of an earlier world; but also by the magnificent view which it

commands. Storr is generally visited by the land route, but when the weather

is favourable the trip may be combined with a boating excursion. Viewing, as

we proceed, a natural bridge of rock in a severed reef running out from

Storr, and then visiting the caves at the south entrance of the bay, of one

of which Martin, in his Western Highlands, says,—"On the south side of Loch

Portree, there is a large cave, in which many sea cormorants do build ; the

natives carry a bundle of straw to the door of the cave in the night time,

and there setting it on fire, the fowls fly with all speed to the light, and

so are caught in baskets laid for that purpose." After leaving the caves the

boat will cross to the north headland, and when passing along the fine cliff

scenery of the coast of Scorribreck, the party may land and visit a cave,

about two miles north from the entrance of the bay, in which Prince Charles

Edward found a temporary, but comfortless refuge, when wandering among the

Hebrides a hunted and miserable fugitive. It is partially encrusted with

stalactite of a yellowish colour, and the entrance is a piece of very

picturesquely ornamented natural architecture, gracefully festooned with

ivy.

A little further on, the boat

will pass the small rocky island of Holm, where, if the party have taken the

trouble to supply themselves with hand-lines and bait, some excellent

fishing may be had, and then proceed to the beach below Storr. This is a

salmon-fishing station during the season; and not far from the

landing-place, a stream, shooting over the face of a lofty cliff, forms a

fine cascade. From the beach to the base of the precipice and pinnacles of

Storr, there is an ascent of varying steepness, but equivalent to a three

miles' walk. Tourists to whom a boating excursion has no attractions, will

probably be content to forego the caves and the magnificent cliff scenery,

and to approach Storr by land. In doing this they may either proceed by a

track through the fine pastoral farm of Scorribreck for about eight miles,

during which, if they be free of the gentle craft of angling, they may have

good sport on the hill-lochs of Fadda and Leathan, which they pass on their

way, or they may adopt an easier, though more circuitous route, and proceed

by the parliamentary road to Snizort, and breaking off at Renitra, advance

to Storr through Glenaulton with very little fatigue.

9. From Portree to Dunvegan

the distance is twenty-two miles. About six miles from the former village it

reaches the head of Loch Snizort, where there is a public-house, and passes

by the house of Skeabost (- Macdonald), fenced by hawthorn hedges, and

sheltered by well-grown trees. A little further on, and clustered together,

stand the Free Church, the manse, and school-house of Snizort. On the

opposite side of the loch are seen the houses of Tote and Skirinish, and the

parish church and manse of Snizort; and beyond them the house of Kingsburgh

(Donald Macleod, Esq.) About two miles beyond Skeabost is the cottage of

Treasland (- Gray), and a mile further on, the public-house of Tayinlone,

being the half-way stage between Portree and Dunvegan.

About a mile and a half from

Tayinlone there is an eminence of considerable elevation, which is

surmounted by one of those interesting vestiges of antiquity, the duns or

round towers. It is a circular dry stone building, the thick walls of which,

though dilapidated, remain yet of considerable height, after having

weathered the storms of more than 1000 years. The view from this dun is very

extensive, including the points of Trotternish and Vaternish, the Minch, and

the distant mountains of Harris. Resuming our journey from Tayinlone, we

next pass the house of Lyndale, pleasantly situated at the sea-side,

surrounded by large fields, and sheltered by thriving wood. The road now

approaches the head of Loch Grishernish, and passes Edinbain and Cushletter.

In descending to these places—in both of which there are numerous patches of

arable land, indicating, by their minute subdivision and defective draining,

the disadvantages under which agriculture is pursued in Skye—we obtain a

glimpse of the mansion-house of Grishernish on the opposite side of the

loch, redeeming, in some measure, by its comfortable and pleasant aspect,

the dreariness which generally characterises the routes from Lyndale to

Dunvegan.

10. At Fairy Bridge, about

three miles from Dunvegan, the Vaternish road strikes off in a northerly

direction, and, proceeding along the northern shore of Loch Bay, passes the

farmhouse of Bay, the mansion-house of Fasach (Major Allan Macdonald), and

the village of Stein, on to Hulin and Ardmore, a district seldom surpassed

in the fertility of its arable land, and the excellent quality of its

pasture. The village of Stein was established by the Fishery Board, and was

once an important station for the herring fishing, but its importance in

that respect is now at an end, the herring shoals having almost wholly

abandoned the west coast of Skye, and betaken themselves to the sounds and

lochs on the east side. A manufactory of tile-drains was a few years ago

established by Macleod of Macleod, at Bay, but the subsequent misfortunes of

that estimable and public-spirited proprietor, brought the undertaking to a

premature close.

11. After leaving Fairy

Bridge, the parliamentary road approaches and passes close to the

plantations which surround Dunvegan Castle. This venerable and imposing

structure, which possesses at once all the amenities of a modern residence,

and the associations connected with the far-away and barbarous time in which

it originated, stands near the bead of a long bay, interspersed with

numerous and flat islands, and formed by two low promontories, between the

extremities of which are seen the distant mountains of the Long Island. To

the west are two hills, which, from their singularly flat and horizontal

summits, are called Macleod's Tables. The castle stands upon a rock

projecting into the water, and protected by a stream on one, and a moat on

another side: it occupies three sides of an oblong figure enclosing an open

area on the side next the sea, which is laid out as a parterre, and fenced

by a low wall, pierced with embrasures. It is a very ancient, highly

imposing, and extensive structure, still in perfect repair, and is the

family seat of Macleod of Macleod. There are two towers, one of which is

said to have been built in the ninth, the other was added in the thirteenth

century. The walls of the former are from nine to twelve feet thick, and

contain many secret rooms and passages. Very considerable alterations have

lately been made on the edifice. The north wing, which was modern, has been

replaced by a building to correspond with the rest of the castle, The walls

of the centre building, which had been slated, have been raised and

surmounted by embrasures, as on the great tower; turrets placed at all the

corners, and the flag-staff tower raised two storeys. The interior has

undergone much alteration and improvement, and altogether, Dunvegan is now

one of the finest buildings of its kind, and one of the most comfortable

residences in the Highlands. The best point of view is the slope of the hill

to the south of the castle; whence the long vista, formed by the

island-studded bay, and terminated by the blue mountains of the outer

Hebrides, composes an admirable back-ground.

Several antiques are

preserved in the family of Macleod, the most remarkable of which are, the

fairy flag, the horn of Rorie More, and a very old drinking cup, or chalice.

Of the fairy flag, only a small remnant is now left: its peculiar virtue

was, at three different times to ensure victory to the Macleods, on being

unfurled when the tide of battle was turning against them. Twice has it been

produced with the desired effect; but the return of peaceful times has

precluded any further occasion for its services, and a portion of its

magical influence is still in reserve for a future emergency. The fairy

flag, which is of a stout yellow silk, is said to have been taken by one of

the Macleods from a Saracen chief during the crusades; but the probability

is, that it had been a consecrated banner of the Knights Templars. The Horn

of Rorie More, a celebrated hero of the house of Macleod, has a curve

adapted to the bend of the arm, by the aid of which its contents can be

conveniently transferred to the mouth, on slightly raising the hand. Each

young chief, on coming of age, should, by ancient custom, drain at a draught

this lengthy wine cup full of claret, being a magnum of three bottles. The

literal achievement of this feat belongs to the manners and men of the olden

times, and the greater part of the horn is now, by a proper and allowable

device, filled up when the ceremony is to be performed. The chalice is a

piece of antiquity of most venerable age and curious workmanship; it is

about a foot in height, rests on four short legs, and is made of a solid

block of oak, richly encased and embossed with silver, on which is a Latin

inscription, in Saxon black letter, engraved in a very superior style,

which, translated, is as follows:-

Ufo, the son of John,

The son of Magnus, Prince of Man,

The grandson of Liahia Macgryneil,

Trusts in the Lord Jesus,

That their works will obtain mercy.

O Nieil Oimi made this in the year of God

Nine hundred and ninety three.

It is said to have been part

of the spoil taken from an Irish chief, "Nial Glundubh"—Niel of the Black

Knees. The author of the admirable Statistical Report of this parish doubts

the correctness of the century; the first nine being very indistinct, and

the introduction of the Arabic numerals into Europe having been only two

years previous to 993, and their use not at all common in western Europe for

a considerable time thereafter. It is, however, unquestionably of great

antiquity, and a very interesting object. These relics accord well with the

high antiquity of the family of Macleod, descended from Liot, or Leod, son

of Thorfinn, son of Torf Einar, first Earl of Orkney, and grandson of

Rognvallar of Norway, brother of the famous Rollo the Dane, founder of the

duchy of Normandy. Leod settled in Lewis, and the Macleods of 'Macleod, or

of Skye, are descended from his son Tormoid, and settled in this island in

the tenth century, while the Lewis 31acleods are sprung from Leod's other

son, Torquil.

12. There is a very good inn

at Dunvegan. On the west side of the bay, opposite Dunvegan Castle, stands

the farmhouse of Uiginish, now the residence of the parish minister of

Durinish. A few miles further down the bay, and close to the shore, is seen

the pleasantly situated mansion-house of Husabost, the residence of Nicol

Martin, Esq., on whose property, and still farther down the bay, is the farm

of Borreraig, once the site of a school or college of pipers, instituted by

the MacCriminons, long the hereditary pipers of the Macleods, and the

acknowledged most accomplished masters of pipe-music in the Highlands,

adding, for several generations, to musical talent other equally

distinguishing qualities. A cave, opening towards the bay, is pointed out as

the place where the disciples received their instructions, and one may fancy

that, issuing from the rock, and mingling with the sounds of the wind and

waves of a wild Highland loch, even the strains of the bagpipe may have been

softened into sweetness and melody. The course of instruction was systematic

and protracted. Macleod bestowed on them the farm of Borreraig, rent free;

but when rents rose, having proposed to resume one-half, but to secure the

remainder to MacCrimmon in fee, the sensitive musician broke up the

establishment; and from that day the Borreraig MacCrimmons dropped their

professional cultivation of the great Highland instrument, though it is

believed their representative, now an officer in the British army, retains

more characters of his race than the family name. A similar establishment

existed in Trotternish, at a place called Peingowen, which was settled by ,MI'Donald

on his pipers, the M'Arthurs; and a little green Bill, called Cnocphail, was

their daily resort, and that of their pupils. Among the other most

celebrated pipe performers in the Highlands were the Macgregors of Fortingal,

the Mackays of Gairloch, the Rankins of Coll, and the M'Intyres of Rannoch.

13. Adjoining Borreraig, and

extending to Dunvegan Head, is the farm of Galtrigil, on which is a stone of

no little celebrity, called Clach Modha, or the tanners' Stone. It is a flat

circular stone, on which, it is said, written characters, probably Runic,

might formerly be traced; but if so, they are no longer distinguishable, and

the stone is now interesting chiefly from its mystic virtue in communicating

to all who sit upon it a degree of politeness and good manners not otherwise

attainable. Should a desire of testing the efficacy of this Hebridean rival

of the celebrated Blarney Stone of Ireland lead any tourist to Galtrigil, it

will be worth his while to extend his walk for a mile further, to Dunvegan

Head, and enjoy the prospect which that promontory offers of the shores of

the Long Island, as they dimly appear on the opposite side of the Minch. On

the face of a precipitous cliff near Dunvegan Head, a curious phenomenon has

been occasionally, though rarely, observed. A jet of vapour or smoke,

resembling the column of steam discharged from the escape-valve of a

steamer, has been seen to issue horizontally from the face of the cliff.

This eruption of vapour is always preceded by a rumbling noise, which

continues for some time, and increases in loudness, until the appearance of

the vapour or smoke. This phenomenon was described to us by three several

individuals resident in Galtrigil, one of whom mentioned, in order to give

an idea of its continuance, that a boy who was herding near the scene, on

one of the occasions when the phenomenon was observed, came running to our

informant's house, which was nearly a mile distant, in a state of much

excitement, to tell of the wonder he had witnessed, and our informant having

proceeded to the place, arrived in time to hear the noise and see the

eruption.

Extending westerly from the foot of Macleod's Tables, and opening upon Loch

Poltiel, is the fine arable valley of Glendale, about the centre of which,

shaded by venerable trees, is the farm-house of Hummir, once the residence

of the enthusiastic and credulous author of the Treatise on the Second

Sight, a curious tract, which has been reprinted in the Miscellanea Scottica.

Thence, a short walk through the moor of Millevaig leads into the secluded

glen of Vaterstein, the soil of which is of excellent quality, terminating

in the rocky peninsula of Feast, the most westerly point in Skye.

14. We may here most

fittingly allude to the, in this country, unprecedented and pitiable story

of Lady Grange. This gentlewoman, the lady of Lord Justice Clerk Grange,

brother of the Earl of Mar, having, contrary to her husband's wish, become

privy to his and others being in concert with the rebel chiefs of the 1715,

and being on bad terms with each other, it was resolved, at a hasty

conference of some of the leading persons, that it was necessary for their

safety to have her removed to a remote part of the country. The chiefs of

Macleod and M`Donald undertook her seclusion, and she was conveyed away by

force, two of her teeth being knocked out in the struggle. Meanwhile, a

report of her death was got up. The unfortunate lady was confined for some

time in some miserable hut in Skye; she was then transported to Uist, thence

to St. Kilda, where she was detained seven years. From that she was carried

back to Uist and Skye. While there she ingeniously enclosed a letter in a

ball or clue of worsted, which was sent with others for sale to the

Inverness market. The purchaser forwarded the letter to its destination. The

consequence was, that government despatched a vessel of war in search of

her. But even the awakened vigilance of the authorities was unavailing. This

persecuted woman was reconveyed to Uist, her conductors having by them a

rope with a running noose and a heavy stone attached, wherewith to commit

her to the deep should occasion require. She finally died in Waternish, and

was buried in the churchyard of Trumpan, in that parish. The perpetration

and the impunity of such a course of outrage strikingly illustrates the

lawless state of the Highlands and Islands previous to the Disarming Act.

15. We have already said that

the Portree and Dunvegan road has been extended through Durinish and

Bracadale to Sligachan, a distance from Dunvegan of about twenty-four miles.

This extension of the road is very interesting to the tourist, as it opens

up to him the fine scenery of Bracadale and Talisker, while it induces him

to prosecute his wanderings, by removing all necessity for retracing his

steps by the dull road between Dunvegan and Portree. Leaving the inn of

Dunvegan, the road passes close in front of the castle, and thence by

Kilmuir, where stands the neat parish church of Durinish, by ti atten,

Feorlig, Caroy, Ose, Ebost, and Ulinish, to Struan, near the head of Loch

Bracadale, where there is a small but comfortable public-house, which

conveniently divides the distance to Sligachan. On the farm of Feorlig, and

close to the road, are some sepulchral cairns of considerable magnitude. At

the head of Loch Caroy stands the only Episcopal chapel in Skye, a small but

neat building. The cure is at present, and for some time back has been

vacant. A few miles further on, on the farm of Ulinish, stands the best

specimen to be found in the island of the Danish dun or burgh, and which is

described by Dr. Johnson in his Journey to the Western Islands. From the inn

of Struan, the road proceeds close to the church of Bracadale, round the

head of Loch Struan, and thence, ascending the hill above Gesto, goes on to

Drynoeb, at the head of Loch Harport, and thence through a fine pastoral

valley to Sligachan, where it rejoins the road to Portree. The whole route

from Dunvegan to Sligachan is very pleasing, and contrasts favourably with

the other lines of road in Skye, which seem, as if of set purpose, to have

been drawn along the bleakest and dreariest tracts of the island.

16. The road to Talisker

breaks of from the Bracadale road at the head of Loch Iiarport, on the south

side of which it proceeds. The distance from Sligachan to Talisker is

thirteen or fourteen miles. About four miles from TaIisker, and on the shore

of the loch, is Carbost, the site of a distillery, where whisky is

manufactured, which, in the opinion of every genuine Skyeman, is unrivalled

in excellence. Around the distillery there is a large extent of arable

ground, improved and brought into admirable cultivation by the spirited

proprietors of that establishment, Messrs. H. and K. M`Askill. The road from

Carbost to Talisker is wild and dreary, giving no indication of the beauty,

warmth, and fertility of the sheltered valley into which it rather abruptly

descends. The house of Talisker (Hugh M`Askill, Esq.) stands at the head of

a singularly rich, flat vale, scooped out, as it were, from the line of

lofty and precipitous rocks which fences that part of Skye, lying open to

the sea on the west, and almost encircled in every other direction by

impending high grounds. The house is surrounded by sycamores and other

trees, of venerable age and large growth, and it possesses a garden, the

products of which, in fruit and flowers, may vie with those of the gardens

of the most favoured parts of Scotland. Behind the house rises a singularly

shaped rock, which may be ascended with some little difficulty, and commands

an extensive prospect. From the cliffs around descend many cascades, more

than one of which present at times a singular spectacle, for the water,

rushing from the edge of the cliff, is met by the blast, and carried up in a

thin, curved column, like the smoke from a cottage chimney, which, falling

into its former channel behind the ledge, again and again renews its

unsuccessful efforts to descend to the lower level.

17. We will now return to

Loch Snizort, for the purpose of shortly describing the district of

Trotternish, along the west side of which a parliamentary commissioners'

road has been opened to the extent of about fourteen miles, terminating

about a mile and a half beyond the Bay of Uig. It strikes off from the

Dunvegan road, within a short distance of the head of Loch Snizort.

Trotternish is the richest district in Skye, and contains a good deal of

excellent arable ground. Passing the church and manse of Snizort, about two

miles from the latter, we leave on the left the house of Kingsburgh. The

circular Bay of Uig is distant five miles from Kingsburgh; and, in the words

of a late eminent writer, whose works, on their first appearance, occasioned

no slight sensation in this and other remote quarters of the Highlands

"presents one of the most singular spectacles in rural economy—that of a

city of farms." The sloping sides of the bay are crowded with houses; and

each cultivable patch of land has found an industrious and successful

occupant. At the head of the bay the ground rises steeply, and environs

about a couple of hundred arable acres, in which some six hundred people

live in a scattered hamlet. A short way from Uig is the old house of

Monkstadt, or Mougstot, for some time the seat of the chief of the powerful

family of MacDhonuill, after Duntulm Castle, the ancient family residence,

had fallen into ruins. On an islet, in a lake, imperfectly drained,

adjoining Monkstadt, are the remains of a religious house; whence, no doubt,

its name is derived, and as in other parts of Skye the remains of round

towers or Danish forts, and of stone circles, are frequent. Duntulm Castle

stands near the point of Trotternish, about seven miles farther on. Little

of it now remains, and it was in no respect different from the ordinary

towers on other parts of this coast. On the way to it will be observed some

beautiful specimens of columnar basaltic rock, and close by it Lydian stone

occurs in small nodules, or layers. Towards the close of the sixteenth

century, the dungeon of Duntulm witnessed the dying agonies of a nephew of

Donald Corm Mor, the then Macdonald, who was here confined for a detected

purpose of conspiring against his uncle. He was fed with salt beef, and then

denied the means of satiating his craving thirst, in the torments of which

he closed his existence. Duntulm was visited in 1540 by a royal fleet, with

which James V. proceeded to the Hebrides, to quell the turbulent island

chiefs, several of whom, including Macleod of Lewis, Macleod of Dunvegan,

and several chieftains of the clan Macdonald, he carried prisoners to the

south.

18. There is a remarkable

bowl-shaped hollow called Quiraing, on a hill top, or rather in the heart of

a hill, on the east side of Trotternish, about three miles distant from

Stcinscholl Bay, and twenty-two miles from Portree, by a good road. It is

approached from Uig, from which it is distant about seven miles. It

resembles the crater of an extinct volcano. The hill may be about a thousand

feet in height, and it presents to the north-east a front of rugged basaltic

precipices, over which various little streamlets occasionally trickle. In

the hollow is a level oblong green platform, measuring 100 paces by 60, and

around rises on all hands a circle of rocks, for most part innaccessible,

rising from the surrounding declivities, and which shoot up above into

detached columnar and pyramidal masses of varied figure. Through the

intervening chasms confined views are obtained of the sea and surrounding

country. As may be readily conceived, the effect, whether of sunshine or

mist, streaming or circling amidst the broken summits of this deeply

imbedded and secluded spot, is not a little singular. The main inlet is by a

steep narrow passage, the access to which is strewed with broken fragments

of stone, and near the entrance of which stands an isolated needle-shaped

rock.

19. Trotternish has long been

familiar to the public as the scene of some of Prince Charles Edward's

adventures. Under the escort of Flora Macdonald—a name which, as Dr. Johnson

predicted, will live in history—he, in the course of his wanderings, after

the battle of Culloden, landed from the Long Island.* Miss Macdonald

repaired to Mougstot to communicate to Lady Margaret, lady of Sir Alexander

Macdonald, and who had been expecting the Prince, notice of their arrival.

Sir Alexander had withheld himself from the rebellion, though one of the

first applied to on the Prince's landing. He, however, had a leaning to the

cause, and the fugitive adventurer found a stanch friend in his lady in the

day of need. The Macdonalds have the proud distinction of having been almost

exclusively the first to join the Prince; and to them he was peculiarly

indebted, during his eventful and extraordinary wanderings, when the sun of

his prosperity had for ever set. No wonder, then, that in parting with

Captain Roy Macdonald at Portree, he should thus have given utterance to his

regret, that "he had always found himself safe in the hands of the

Macdonalds; and so long as he could have a Macdonald with him, he still

would think himself safe enough." A party of soldiers were, at the moment of

Miss Macdonald's appearance, stationed in the house of Mougstot. Miss

Macdonald remained in the house, to converse with the officer in command,

while Lady Macdonald, Mr. Macdonald of Kingsburgh, and Captain Donald Roy

Macdonald, who happened to be there at the time, in the garden, concerted

measures for the Prince's further progress, who had, in the meantime, stayed

at the beach. The Prince and Kingsburgh walked together to the residence of

the latter, which has been mentioned above. Miss Macdonald proceeded to the

same quarter on horseback, along with a Mrs. Macdonald, Kirkibost, North

List, and their servants; while Captain Macdonald went in search of young

Macleod of Rasay, to whose keeping, and that of his kinsmen, the adventurer

was shortly afterwards committed.

At Kingsburgh the poor Prince

seems to have given way to the overflowings of his heart at the temporary

relaxation from the hardships to which he had lately been subjected. His

host and he became quite like two intimate friends of equal rank and long

acquaintance. The little china toddy bowl was replenished once and again;

and it was only after a friendly altercation, on Kingsburgh insisting on

removing the bowl, and in the course of which it was broke, that the Prince

could be persuaded to retire to rest. From Kingsburgh, changing his female

habit for the Highland dress, he proceeded next day to Portrec, where

Captain Malcolm Macleod, and two sons of Macleod of Rasay, took charge of

him, and conducted him, first to Raaza, and afterwards to Scorribreck, in

Trotternish. At Scorribreck, we are told by Captain Macleod, that he "

entreated the Prince to put on a dry shirt, and to take some sleep ; but he

continued sitting in his wet clothes, and did not then incline to sleep.

However, at last he began to nap a little, and would frequently start in his

sleep, look briskly up, and stare boldly in the face of every one of them,

as if he had been to fight them. Upon his waking he would sometimes cry out,

`Oh, poor England! oh! poor England! "'

Captain Macleod and the

Prince went from Scorribreck to Strath, where the old Laird of Mackinnon and

Mr. John Mackinnon, Ellighuil, undertook to convey him to the continent of

Scotland. The party landed on the south side of Loch Nevish, opposite the

point of Sleat, and afterwards sailed up to the head of the lake, making a

very narrow escape from a boat with a party of armed men, by whom they were

pursued. They directed their steps to Borradale. Meantime, the military

hearing of his having landed,had adopted precautions which promised to

render escape impossible, having placed a chain of sentinels within sight of

each other, between the terminations of the various long arms of the sea and

fresh-water lakes, by which the country is indented from Loch Hournhead to

the head of Loch Shiel. Large fires were at night lighted at the different

posts, and the sentinels kept constantly in motion from fire to fire. One

only chance was inadvertently left. The sentinels passed each other between

the fires, and thus for a few minutes, when their backs were turned, the

space between was left unobserved. Accompanied by Mr. Macdonald of

Glenaladale, and two other gentlemen of the same name, and by Mr. Donald

Cameron, Glenpocan, the Prince skulked about within the enclosed grounds in

the most imminent danger; but at length taking advantage of the imperfection

in the toils of their adversaries, they succeeded in making 'their way up

the course of a small mountain stream between two posts, towards the head of

Loch Mourn.

Hence they hied them to Glen

Moriston, and Charles spent three weeks in a cave in a high mountain between

that glen and Strathglass, tenanted by seven men, whose occupation was

plunder, yet who, notwithstanding the large price set on the Prince's head,

tended him with the greatest fidelity and kindness, putting themselves to

much trouble to supply his wants, and even occasionally procuring him the

newspapers of the day.

Removing to Lochaber, the

Prince for some weeks lived concealed, along with Mr. Cameron of Clunes,

among the recesses of the woods and mountains bordering Loch Arkaig and Loch

Lochy. At last he was enabled to join Lochiel and Cluny, who were securely

secreted on the confines of Perthshire, and with whom he remained for about

three weeks, in the memorable cage, a half aerial habitation, in the rocky

face of Benalder, amidst the even now remote solitudes of Loch Ericht. Here

intelligence reached him that two French vessels, sent on purpose, were

lying waiting him in Loch-na-Nuagh; whither he immediately hied him with his

friends: "and thus was he destined," as Mr. Chambers remarks, "like the

hare, which returns, after a hard chase, to the original form from which it

set out, to leave Scotland, where he had undergone so long and so deadly a

chase, precisely at the point where he had set foot upon its territory." A

considerable body of fugitives, with their friends, were soon assembled upon

the shore, opposite the vessels. The unfortunate prince attempted to brave

the desperation of his fortunes, by holding out prospects of a brighter

season, when he should return under circumstances to insure the means of

recompensing his gallant Highlanders for all their devotedness, and all its

consequences. "But the wretchedness of his present appearance was strangely

inconsistent with the magnificence of his professed hopes. The many noble

spirits who had already perished in his behalf, and the unutterable misery

which his enterprise had occasioned to a wide tract of country, returned to

his remembrance; and looking round him, he saw the tear starting into many a

brave man's eye, as it cast a farewell look back upon the country which it

was never again to behold. To have maintained a show of resolution under

circumstances so affecting, was impossible. He had drawn his sword in the

energy of his harangue, but he now sheathed it, with a force which spoke his

agitated feelings; he gazed a minute in silent agony, and finally burst into

a flood of tears. Upwards of a hundred unfortunate gentlemen accompanied him

on hoard; when the anchor being immediately raised, and the sails set, the

last of the Stuarts was quickly borne away from the country of his fathers."

The remains of Flora

Macdonald, latterly Mrs. Allan Macdonald of Kingsburgh, after an eventful

life, of which part was passed in North Carolina during the American war,

lie interred within the Kingsburgh burying-ground, in the churchyard of

Kilmuir, in Trotternish. She died in 1790. A good portrait of her may be

seen in the town hall of Inverness.

We are aware of the

geological appearances of Skye being extremely important and interesting,

though the plan of our present volume does not admit our enlarging on them.

The preceding sketch, and the next division of the present section of our

subject, will be found, we trust, to contain a sufficient number of

practical directions to the tourist, and descriptions of all the general

features and most important objects in the island. |