|

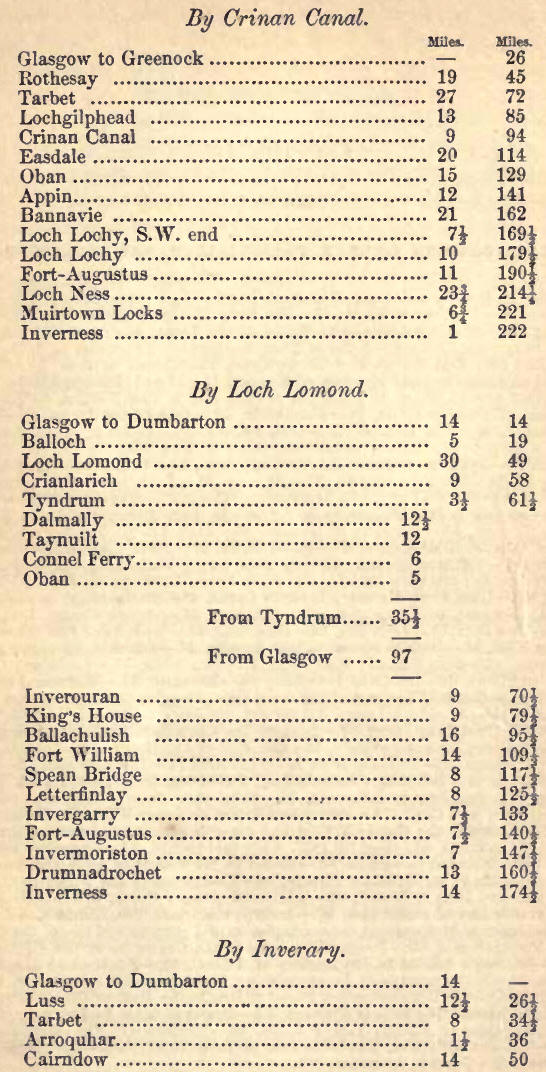

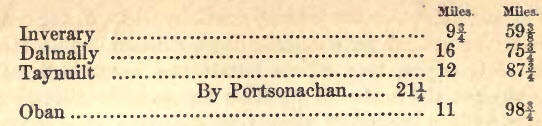

SECTION III.

ROUTE I.

FROM GLASGOW TO OBAN,

FORT-WILLIAM, AND INVERNESS.

Diversity of Routes, and

their Characteristics, 1.-By Crinan Canal.-The River Clyde, 2.-Dumbarton

Castle, 3.-The frith of Clyde, Greenock, 4.-Dunoon Castle, 5.-The Ayrshire

Coast; Battle of the Laws, G.-Toward Castle, 7.Rothesay, and Castle,

8.-Kyles of Bute, 9.-Argyle s Expedition in 1685, 10.-Loch Fyne; East Tarbct,

11.---Crinan Canal, 12.--Crinan to Oban, 13 -Whirl- poo1 of Corryvreckan,

14.-Isle of Kerrera, 15.-Oban; Dunolly Castle, 16.-District around Oban,

17.-Glasgow to Oban and to Fort-William, by Loch Lomond.-Preferable Route,

18.-Dumbarton, 19.-Vale of the Leven, 20.-Loch Lomond, 21.-Ben Lomond,

22.-Glen Fallocb, 23.-Battle of Clenfruin; The Clan Gregor, 24.-Robert

Bruce's encounter in Glen Dochart, 25.-St. Fillan's Pool, 26.-Tyndrum to

Dalmally, 27.-Loch Awe; Ben Cruachan, 28.-Kilchurn Castle, 29.-The Pass of

Awe, 30 -Bunawe, 31.-Loch Etive, 32.-Ardchattan Priory, 33.-Connel Ferry,

34.-Dunstaffnage Castle, 35.-Berigonium, 36.-Oban, 37-Glasgow to

Fort-William, by Loch Lammed.-Loch Tollic; The Black Mount, 38.-Glencoe,

39.-Massacre of Glencoe, 40.-Loch Leven; The Serpent River; The Falls of

Kinlochmore, 41.-Ballachulish, 42.-From Glasgow to Oban, by

Inverary.-Diftcrent Routes, 43.-By Loch Long-loch Long, 44.-Glencroe; Glen

Lochan ; and Glen Finlass, 46.-Loch Fyneyy Fyne; Dunedera Castle, 46.-Inver-

ary, 47.-LochFyneHerring ; Inverary Castle, 48.-To Inccrary, by the Gareloch,

Lochgoile, and Loch Eck.-The Gareloch, 49.-Carrick Castle; Lochgoile,

50.-Holy Loch, 51.-Loch Eck, 52.-Glen Aray, 53.-Loch Awe; Port Sonachan ;

Glen Nant, 54.-Oban to Inverness. Loch Linnhe, 55.-Island of Lismore;

Auchindoan, 56.-Fort-William; biaryburgh, 57.-Ben Nevis, 58.-Lochaber;

Castle of Inverlochy, 59.-Battle at Inverlochy 60.-Bannavic, 61.-Monument at

Corpach, 62.--General Character of the Great Glen, 63.-Tor Castle, 84.-First

Skirmish in 1745, 65.-Loch Lochp ; Achnacarry, Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochicl,

66.-Battle of Cean, Loch Lochy, 67.-Laggan ; The Kennedics; The late

Glengarry, 68. -Loch Oich; Invergarry Castle, 69; The Well of the Heads,

70.-Loch Oich to FortAugustus, 71.-}'ort-Augustus, 72.-Loch

Ness,73.-Invermoriston, 74.-Falls of Foyers, 75.-Boleskine ; 'Inverfarikaig,

76.-Bona, or Bonessia; loch loch. four, 77; Dochfour to Inverness,

78.-Caledonian Canal-Adaptation of the Great Glen for a Canal, 79.-Survey

and Report by James Watt, 80.-Reasons for the formation of the Canal;

Telford and Jessop's survey, 81.-General description of the Canal, 82.-Cost

till 1827, when first opened, 83.-Imperfect state of the undertaking at this

period, 84.-Report by fir Walker in 1838, and nautical investigation by Sir

W. Edward Parry, 85-Completion of the Works by Messrs Jackson and Bean in

1843-7, 86.-Alditional outlay; Extent of accommodation for vessels and of

traffic now, 87.-Incorporation with the Crinan Canal, and Commission of

Management, 88.-Adaptation of Inverness and line of the Canal for

Manufactories, 89.-Prospective results to the Commerce of the Highlands,

90.-Southey's tribute to the memory of Telford, 91.-Roads along the Great

Glen, 92.-Fort-Augustus to Invermoriston ; Lower part of Glenmoriston,

93.Invermoriston to Drumnadrochet, 94.-Aultsigh Burn; Raid of Cillie-Christ,

95. Glen Urquhart; The Falls of Dhivach, 96.-Drumnadrochet to Inverness,

97.-Fort Augustus to Foyers; Vale of Killen, 98.-Stratherrick; The River

Foyers, 99.-The General's Hut, 100.-The Pass of Inverfarikaig,

101.-Inverfarikatg to bores, 102.-Doren to Inverness, 103.

1. THE circuit from the

metropolis of the west of Scotland to that of the Highlands, by the coasts

of Argyleshire and through the Great Glen, is the route most frequented by

the crowds of tourists attracted each succeeding season to the north of our

island. In this tour great variety of choice may be indulged, as one has the

power of making the whole journey by steamer, through the Kyles of Bute and

the Crinan Canal—of being transported by coach either to Oban or

Fort-William, with a water trip intervening on Loch Lomond. Or the traveller

may take Inverary on the way; to it again, selecting as it may be either of

the accesses by Loch Lomond, the Gareloch, Loch Long, Loch Goil, Loch Eck,

or Loch Fyne. As each and all of these lines of direction are replete with

the very finest features of mountain and water scenery, and converge upon

the western extremity of the Great Glen of Scotland, with its chain of

inland lakes connected by the Caledonian Canal, and uniting the Moray Firth

with Loch Linnhe, which respectively at either end prolong this grand valley

into the German and Atlantic Oceans, the attractions of this favourite route

can be readily understood. There is, indeed, certainly nothing within the

compass of the British islands at all to be compared with it in point of

extent of continuous grandeur, diversity, and beauty. The whole is

singularly magnificent, and far from palling by repetition, each new

peregrination will be found to add fresh zest to the enjoyment of the

incomparable scenery through which we are conducted. Now, too, the steamers

and other conveyances are of a much improved class, and large and commodious

inns have been erected at Ardrishaig, on the Crinan, and at Bannavie, on the

Caledonian Canals ; the access to this last being further improved by the

construction of a suspension bridge across the river Lochy, near

Fort-William. The whole distance is accomplished in from a day and a half to

two days —the intermediate night (by steamer) being spent at Bannavie on the

way north, and at Oban on the way south. Coaching between Glasgow and

Fort-William or Oban makes no difference in time, except on the journey

north by Oban, as the coaches do not arrive in time for the same day's

steamer. The Messrs. Burns of Glasgow, into whose hands the great bulk of

the traffic alongst the routes in question has passed—though after all but a

trifling branch of their very extended establishments —are laying themselves

out by a constant adaptation of the resources at their command, to the

increasing demands of the public, to afford accommodations in every

department of a superior order, and to provide ample facilities of

communication in every eligible direction, and at very moderate charges.

Of these different routes,

that

By the Crinan Caron,

as longer familiar to the

public, may with propriety take precedence.

2. This route is entirely a

marine excursion. There is no land journey. But the steamers' pathway is so

completely landlocked, that there are no high seas to be encountered, though

at times, in passing the Slate Islands, the swell from the Atlantic in fresh

weather may somewhat discompose unaccustomed constitutions.

We must leave to others the

description of the great emporium of the commerce, wealth, and enterprise of

Scotland. Wending our way then at once to the Broomielaw, we embark in one

of the well-appointed swift steamers which now daily during the

season—besides luggage boats all the year—convey their respective quota of

passengers to Inverness and the places intermediate. The channel of the

river Clyde being now deepened, so as to admit vessels of large draught up

to Glasgow, its wharves are found crowded with shipping and steamers of all

sizes and dimensions. Along the river banks are seen the hulls of immense

iron and other steam-vessels, in various stages of progress, the Clyde

shipbuilders and machinists having attained a high reputation; and the tall

receding chimney stalks giving out incessant volumes of murky smoke—that of

St. Rollox far pre-eminent, reaching as it does a height of more than 400

feet, continue to testify to that manufacturing industry, of which our

sojourn in the city had already furnished perhaps overabundant proofs.

Imposing lines of buildings extend in the back ground on the north, and

numerous villas bedeck the face of the country on the south bank. About a

couple of miles down the river the villages of Govan on the left, and of

Partick on the right hand, meet the eye. On either hand the country is low

but fertile; and as the boat passes along, some fine mansions, as Jordanhill

and Scotstown, Elderslie and Blythswood, claim attention. About six miles

down, the house tops of the ancient burgh of Renfrew are descried on the

left, and further inland the smoke of Paisley indicates its position. Some

miles on, passing the villages of Old and New Kilpatrick, the birthplace of

St. Patrick, we come to Port Dunglas, and the remains of its Roman fortress,

marking the western extremity of the old Roman wall or Graham's Dyke which

extended between the two firths, and to Bowling Bay, at the termination of

the Forth and Clyde Canal. Here a small obelisk commemorates the enterprise

and ingenuity of Mr. Henry Bell, who originated that steamer traffic to

which the Clyde owes so much of its opulence. On the southern shore, as we

near Dumbarton, Blantyre House (Lord Blantyre), a princely mansion, commands

admiration from its extent and elegance, and finely wooded parks. On the

north the Kilpatrick trap hills run in upon the water.

3. Dumbarton's isolated rock,

protruded to an elevation of upwards of 200 feet, at the confluence of the

Leven and Clyde on the north side of the latter river, with its bristling

batteries, forms a conspicuous object in a landscape of surpassing richness

and brilliancy. It is basaltic, and in many place columnar, and is split

into twin summits. The governor's house stands in a recess on the south

side, not much above the base of the rock : from it a steep ascent, by

flights of steps between a narrow gap, conducts to the confined space

between the two summits, at the further end of which are erected the armoury

and the barracks. The former contains 1500 stand of arms ; the latter can

accommodate about 150 men. Within the memory of man, the entrance was by a

footpath up the sloping hank formed of debris on the north side. In the

armoury is kept Wallace's great double-handed sword, an interesting memento

of the mighty dead. The guns of the fortress, sixteen in number, are

arranged about the governor's house, in the face of the highest rock, nearly

in the same line, and pointing down the firth, behind the barracks, and on

the top of the lower eminence. A very old fragment of masonry remains on the

latter, but coeval with what period tradition gives no note. In "Balclutha's

walls of Towers," mentioned by Ossian, we recognise Dumbarton's castellated

rock. It was the capital of the Strathclyde Britons. Alcluith is mentioned

by Bede as orbs munitissimac; and the possession of it being always regarded

as a matter of importance, it figures repeatedly in the stormy history of

our country. Still it was not one of the four principal fortresses given to

the English in 1174, in security of the ransom of William the Lion, and it

is believed to have been at that time only the principal residence of the

Earls of Lennox, the third of whom, Maldwin, surrendered it into the hands

of Alexander II. On one occasion it was the scene of a most adventurous

exploit. We allude to the perilous but successful escalade by Crawford of

Jordanhill, during Queen Mary's reign. While in the possession of her

partisans, this officer of the Regent Lennox, with a few followers, on the

2d May 1571, achieved the daring enterprise of scaling the dizzy precipice,

under cloud of night, surmounting in their progress an unexpected and a very

embarrassing difficulty. One of the party, in ascending a ladder, was seized

with a fit of epilepsy. As the profoundest silence was necessary, the most

imminent hazard arose of their being discovered by the man's falling, or the

noise unavoidable in attempting his removal. The expedient however was

promptly adopted, of making him fast to the ladder, which was then turned,

and his comrades were thus enabled to pass, and reach the summit unobserved.

A striking picture is

presented as we pass the mouth of the Leven, when the town behind the

castle, and its ship-building yards, and its glass-house cones, combine with

the castellated rock as a foreground to the fair and fertile vale of Leven,

bounded in the distance by the pyramidal summit of "the lofty Benlomond."

The panorama from the top of the castle rock is extensive, varied, and

beautiful, of the river and Firth of Clyde, the Leven, and the Highlands

girdling in various but unseen fresh and salt-water lochs. An eminence on

the elevated ground, intermediate between the Leven and the Gareloch, and

not far from Dumbarton, is interesting, as the site of the castle in which

Robert Bruce frequently resided, and in which he died.

4. We are now fairly on the

expanding bosom of the Firth, skirted by fertile sloping shores, diversifies

with intermingling woods. At Port Glasgow, now somewhat of a misnomer, as it

continues but partially to fulfil that relation, Newark Castle, a large

quadrangular pile by the sea, with numerous chimney stalks and hanging

turrets, momentarily recalls us from the busy present to the days of other

years. On the opposite coast the long extending houses of Helensburgh, one

of the favourite sea-bathing villages which abound on the Clyde, mark the

entrance to the Gareloch, concealed behind the wooded peninsula of Roseneath,

on which may be descried an elegant Italian villa, a seat of the Argyle

family.

Greenock, the birth place of

Watt, is an important and bustling sea-port. Its prolonged and many-peopled

quay, with its spacious and handsome custom-house, backed by docks filled

with shipping, is all alive with the hurry of arriving and departing

steamers.

The reach of the Firth to the

Cloch Light-house, where the coast line bends to the south, is one of

uncommon character. On the north its waters sweep backwards to the circling

hills, amongst which they indent themselves in the embracing arms of the

Holy Loch, Loch Goil, and Loch Long. Holy Loch is studded with an

uninterrupted zone of neat and ornamental and cheerful villas, forming and

connecting the villages of Duneon and Kilmun. On the south the villas

adjoining Greenock and Gourock equally betoken the eager concourse of the

teeming population of Glasgow for the enjoyment of the healthful influences

of salt water and the sea breeze. The shores around are lined with one

beauteous frame of cultivated and wooded slopes. The sterner features of

alpine scenery in the ranges of high and rugged mountains to the north,

contrast with the softer graces impressed by the hand of art on the low

grounds. Steam-boats glide along the water, while trading vessels, with, it

may be, a sprinkling of yachts and pleasure boats, with less undeviating

speed, are fain to woo the uncertain breeze. It is difficult to conceive,

without witnessing, the thoroughfare of steamers which the Clyde presents.

In the season the streets of Glasgow are almost literally deserted by the

fairer portion of the inhabitants, who flock to summer quarters on the

Clyde, some as far removed as Rothesay, Largs, Ardrossan, and Arran,

distances of forty to fifty miles and more, while their lords (of the

married portion) find their way down as often during the week as

circumstances permit; but on the Saturdays, or on Friday afternoons, they

literally crowd the steamers' decks, as fully bent on holiday relaxation as

when in schoolboy days they made weekly escape from restraint, returning to

their several avocations on the Monday morning. The privilege to the

population of such a ready and noble outlet is unspeakable, while the

consequent enrichment of the coast, with the enlivening movement of this

living tide, co-operate to heighten the attractions of this magnificent

estuary, which, taken all in all, is unrivalled in the three kingdoms. The

cabin fares are less than a penny, in some instances not exceeding a

halfpenny, a mile. All this life upon the water is, notwithstanding the

rivalry of a parallel line of railway from Glasgow to Greenock, another by

Paisley to Ardrossan, and now a third in progress on the north side of the

river, to connect the city with Loch Lomond.

5. On a green rocky knoll

projecting from the centre of the village of that name, are the foundation

walls of the ancient Castle of Dunoon, which seems to have been little more

than a single tower. It originally owned the hereditary High-stewards of

Scotland as its proprietors ; and it was bestowed on the Argyle family by

the crown in return for the important services rendered in aid of Robert the

Steward, in Edward II.'s reign, by Sir Colin Campbell of Lochow. Dunoon

Castle %vas taken by Edward Baliol, and retaken by Robert Stewart, grandson

of Robert Bruce, about the year 1334. It was a favourite place of resort of

that monarch for the enjoyment of the chase. On one of these occasions an

attempt to surprise him was made by Aymer de Valence, accompanied by 1500

horsemen ; but the Bruce having got intimation of the design, encountered

and defeated them in Glenderuel. Dunoon Castle was also taken in 1544 by the

Earl of Lennox, after a gallant resistance by the Earl of Argyle. It formed

the residence of the Argyle family till about the end of the seventeenth

century. Dunoon was also a Diocesan residence at one period. It is now one

of the most fashionable bathing-places on the Clyde.

6. The steamer's course now

keeps the northern or western shore, but the Ayrshire coast is sufficiently

near to enable us to appreciate the range of low beach, surmounted by

hanging woods, verdant pastures, and corn-fields. Various little enchanting

indentations as at Innerkip—where Ardgowan, the mansion of Sir .Michael Shaw

Stewart, peers forth from an affluence of foliage mantling the hill-sides ;

and Wemyss Bay, each present their clustering villas ; and marine residences

of manufacturing and commercial magnates continue to dot the shore line on

either hand. At the Bay of Largs there is a village of some

pretensions—another at Fairlie of smaller size, but almost wholly composed

of handsome residences, with enclosed garden-grounds of exuberant

vegetation, and those near the water's edge each provided with its

appurtenance of a boathouse. But these places are barely discernible. Largs

is remarkable as the scene of the great battle, or more correctly, of the

series of desperate skirmishes, in which Haco, King of Norway, was defeated,

with great slaughter, in 1263, and the power of Norway in the west of

Scotland irretrievably broken by the Scottish army under Alexander III. A

curious sarcophagus, quite entire, formed by huge and undressed slabs, on a

plateau immediately above the extremity of Largs, on the Fairlie road, would

seem to indicate the thick of the fray, or the spot where some great leader

fell.

In front of us, as we

advance, the Island of Bute to the north, with the small isles of the

Cumbrays, towards the Ayrshire coast, and between and beyond the highly

imposing elevation of the Island of Arran, Goatfell, and contiguous peaks,

conspicuous amongst its lofty and rugged summits, form a fine and varied

screen. In the remote distance we may detect the conical form of Ailsa

Craig.

7. On to the Point of Toward,

the extremity of the peninsula of Cowal, are a lighthouse and the ruins of

Castle Toward, the ancient stronghold of the Lamonts, and a splendid modern

mansion of the same name, the seat of Finlay, Esq.

Of the old castle, which

stood on a detached mound in front of a now wooded hill a little westward of

the Point, but a single tower remains. The offices of the modern building

are erected as for an outwork and gate of entrance to the castle, of which

the design is showy, but wanting in the massiveness and imposing effect of

the gloomy strongholds of the olden time. On passing the east coast of Bute,

Mount Stewart, the seat of the Marquis of Bute, comes into view. Should the

tourist's arrangements lead him to a sojourn on the island, he will be much

gratified by the great growth of the timber and extensive range of the woods

about this seat, and he will find here, too, a fine collection of paintings.

8. The Island of Bute is

nearly eighteen miles long by five broad. Rothesay, an ancient burgh, is a

favourite resort, in summer, of the inhabitants of Glasgow. Its

crescent-shaped and deeply imbedded bay is well protected by the encircling

hills. The population is about 4000 ; and, depending partly on letting

lodgings, the villas about are numerous, and varied in their style and

sizes, and much attention is paid to the cleanliness of the place, while its

fine and well-filled harbour lends it unusual animation and interest. The

fineness of the climate adds a fresh charm to the wayfarer in the luxuriant

shrubberies fronting the bay—fuchsias, in particular, attaining quite a

remarkable size; while its salubrity recommends it to the invalid for the

invigorating of the bodily frame. The principal inns are the Bute Arms and

the Clydesdale. This town, in addition to its healthy and romantic

situation, is rendered interesting by the ruins of its magnificent, old, and

ivy-cased castle, which is supposed to have been built in the eleventh

century, and was long a royal palace, and the scene of the death of Robert

III. Rothesay Castle was reduced by Iiaco, King of Norway, in his expedition

in 1263, and was subsequently held by Rudric, one of his officers, whose

daughter intermarried with the Stewards, its previous possessors. The

building is of considerable extent, there being connected with the palace a

spacious circular court, about 140 feet in diameter, formed by high and

thick ivy-cased walls; on the outside of which a terraced walk extends

around the castle, separated from the adjoining grounds by a wide and deep

ditch. This castle was partially injured by Cromwell's soldiers; and the

work of destruction was completed by a brother of the Earl of Argyle in

1685. Close by the castle is a large new jail and court-house. Several

graceful church spires serve to make up a most striking picture from the

water, especially where the towering ridges of Arran come into view in the

back ground. A green knoll on the west side of the bay, surmounted by the

ruins of an old chapel, commands a view of a low valley which stretches

across the island to Scalpsie Bay on the opposite side of the island, and

containing the waters of Loch Fad, but slightly elevated above high water

mark. This valley is finely cultivated, and intersected by large ash,

sycamore, and beech; and on a ridge, descending into it, stands the parish,

church, and the remains of a Roman Catholic chapel, in the walls of which,

under two canopied recesses, are full-sized e~gies in stone, which, with one

in the centre of the floor, are locally held to represent three brothers,

called "the stout Stewarts of Bute," companions in arms of Sir William

Wallace, and who fell at the battle of Falkirk. The shores of Loch Fad were

selected by Kean the tragedian as a place of residence.

9. The Kyles of Bute, in

their general character, are exceedingly pleasing, as they wind between

moderately-sized hills of undulating and unbroken outline, frequently

sinking sheer upon the water, and seeming to landlock the passage ; heathy

towards their summits, but verdant below, and there fringed with irregular,

waving lines of copse-wood and young plantations and stripes of cultivated

ground. Mingled agricultural and pastoral features, with successive

headlands and windings of the sea, are the characteristics which thus

distinguish the Kyles. Yet, from want of any marked features, perhaps the

general impression is rather one of disappointment. At the head of Loch

Strevan we perceive the terminating chains of the Highland mountains

disposed in several lofty rather detached rounded cones, verdant but devoid

of trees ; while towards Toward Point the softening ranges subside in wooded

and cultivated slopes. About two miles from Rothesay the steam-boat passes

the bay and village of Port Bannatyne on the Bute shore at the east end,

with Kaims Castle, an old castellated mansion, at the head of the bay.

Opposite Rothesay is the house of Achinwillan.

10. At the entrance of Loch

Ridden, on the right, and about the centre of the Kyles, on the islet of

Eilangreig, are seen the ruins of a castle which was garrisoned in 1685 by

the Earl of Argyle in his unsuccessful enterprise, and dismantled by some

English ships sent for the purpose.

Argyle, having opposed, and

afterwards refused to subscribe, a test which was devised by government

against the free principles cherished by the more determined friends of

Protestantism, had been tried and condemned as guilty of treason ; but he

contrived to effect his escape from Edinburgh Castle, and took refuge in

Holland. Here, with other disaffected refugees of distinction, he concerted

an expedition to Scotland, and sailed from Rotterdam with three ships and

about 300 men ; the Duke of Monmouth, at the same time, taking charge of a

similar small armament to make a descent on the coast of England. Partly

from want of due precaution in the Orkneys, intelligence of Argyle's

movements and force was furnished to government, so that adequate

preparations were made to oppose him. He however collected a small army of

2500 of his own and other clans ; but, remaining too long inactive in

Argyleshire, he was hemmed in by superior numbers ; and, his followers being

eventually obliged to disperse, he was taken prisoner at Inchinnan, near

Renfrew, carried to Edinburgh, and beheaded on the 26th June, 1685, meeting

death with distinguished fortitude. Monmouth, equally unfortunate, suffered

a like fate on Tower Hill. Argyle had deposited his stores, to the amount of

5000 stand of arms, and 300 barrels of gunpowder, in Eilangreig, under the

charge of a garrison of 150 men, who abandoned the castle, without offering

any resistance, to a royal squadron, which also captured Argyle's vessels,

and destroyed the fortifications.

11. Passing on the left the

dark mountains of Arran, from every point of view a striking group, from

their beetling precipices and strongly defined outlines, and rounding

Ardlamont Point, the steamer enters Loch Fyne. Skipness Castle, to be seen

on the coast of Cantyre, was one of the most capacious strongholds in the

Highlands ; being surrounded by a high and extensive wall, and the area

subdivided by a cross wall into two compartments, within one of which stands

the ancient square keep of four storeys, still inhabited ; having also two

other small projecting square towers. The shores of Cowal, on the right, are

low and uninteresting, and the hills without character; the Knapdale coast

pretty high, wild, and unattractive.

East Tarbert Bay, where a

narrow isthmus joins Knapdale with Cantyre, surrounded with exceedingly

bare, rough, rocky knolls, with the frowning ruins of its castle, is

uninviting, so that there is no room for regret that we are denied a close

inspection ; but the bay is a secure anchorage, and the village a

flourishing one, and contains an excellent inn. The ancient keep, of four

storeys, perched on a high rock, near the entrance on the southern shore,

with the hanging ruined outer wall, which encircled a very irregular area,

perhaps two acres in extent, and within which may have been a whole colony

of huts, besides the garrison, and larger buildings, are all that remain of

the old castle which was built by Robert the Bruce. Like Skipness on the

same coast of Cantyre, the tower has its staircase in the heart of the

strong thick wall, and has no corner turrets : the rooms were small, but

plastered ; and the outer screens had large round towers at intervals, two

in particular, between which was the main approach, but none entire. Ivy and

rank grass overtop the whole. A scheme was of late years projected for

uniting East and West Loch Tarbert by a canal, which would have been of

importance, particularly to the trade of Islay. For the, present it is in

abeyance.

12. Arrived near the thriving

village of Lochgilphead, a disembarkation takes place, the windings of the

Crinan Canal having to be threaded in a light track boat. The process, and

of re-embarkation again into another steam vessel at the further extremity,

occasions a rather disagreeable anxiety for the safe forwarding of one's

luggage, though the attendants are very careful in seeing after the

transmission of every package. Still, there might be some amendment in

regard to such small articles as may take injury, yet prove rather

cumbersome to carry one's self. The variety of conveyance is in itself a

pleasing change. This canal, intersecting the root of that long promontory

known by the name of Cantyre, is about nine miles in length. From the

dimensions of the locks, which in this short space are no fewer than fifteen

in number, each ninety-six feet in length, by twenty four in breadth, and

the sharp windings of the waterway, its utility in saving the doubling of

the Mull of Cantyre, which is both tedious and hazardous, is confined to

vessels of small burthen. Out out of banks of mica slate, which are

surmounted by brushwood and trees, and festooned with honeysuckle and other

plants, while an extensive moorland accompanies us on the right, the

navigation is highly pleasing and picturesque. This is especially so at the

outset, where the grounds of Achindarroch House or Oakfield (Campbell) lie

alongside, and on the other hand, Kilmorie Castle (Sir John Ord) embellishes

the view.

13. Arrived at the further

end, and on board the steamer in waiting there, as the detention at the

locks generally induces a good deal of walking, all parties find themselves

pretty well prepared to appreciate the well-ordered appointments of the

dinner-table. Quitting the Bay of Crinan, Duntroon—a modernized castle (

Malcolm), forms a conspicuous object. The run hence to Ardincaple Point,

south of Kerrera Sound, is an interesting part. of the, voyage. The numerous

detached objects, islands, mountains, headlands, bays, and inlets, broken up

into successive compartments, in their rapid transmutations, keep the

attention excited. The lofty conical mountains, hence called the Paps of

Jura, are objects too striking not to be alluded to. Off the point of

Craignish, near the Bay of Crinan, are several beautiful and picturesque

islands; and along the coast the trap dykes assume fantastic castellated

appearances. Loch Craignish, an arm of the sea, is distinguished by a chain

of islands in its centre, stretching longitudinally alongst it in a line

parallel with the shores, and composing, in their varied bold rocky, and, in

some places, cultivated and wooded spaces, with similar flanking coasts, a

landscape peculiar and striking, of which a glimpse is obtained.

14. Corryvreckan, the strait

between the northern extremity of Jura and the mountainous island of Scarba,

possesses a widespread notoriety. The commotion of the tides pouring through

this narrow passage is heightened by a large sunk rock. This dangerous

communication is studiously avoided by vessels and to small craft at certain

times it would prove sure destruction. The author of the old Statistical

Account of Jura gives us the following graphic picture of this whirlpool:

"The gulf is most awful with the flowing tide; in stormy weather with that

tide it exhibits an aspect in which a great deal of the terrible is blended.

Vast openings are formed, in which, one would think, the bottom might be

seen; immense bodies of water tumble headlong as over a precipice, then,

rebounding from the abyss, they dash together with inconceivable

impetuosity, and rise foaming to a prodigious height above the surface. The

noise of their conflict is heard throughout the surrounding islands."

"On the shores of Argyleshire,"

says Campbell the poet, "I have oftened listened to the sound of this

vortex, at the distance of many leagues. When the weather is calm, and the

adjacent sea scarcely heard on these picturesque shores, its sound, which is

like the sound of innumerable chariots, creates --a magnificent and fine

effect." Mariners never choose to tempt the rangers of this gulf. Vessels of

burthen, however, can make the passage; and at particular times it is

tranquil enough for boats to venture.'

15. Nearing Loch Feochan, the

steamer's course lies through intricate groupes of islands, Luing, Seil,

Shuna, Lunga, Easdale, and many others, on which there are excellent slate

quarries. These, with the workmen's houses, and vessels shipping cargo, are

an animated scene. They are near the shore, and the steamer runs between and

across the opening of Loch Melford.

The dark mountainous Island

of Mull, with its iron-bound shores, and the hills of Morven, famed in song,

are now seen to close in the seaward view. But in entering on that long

stretch of inland sea called Loch Linnhe, the attention is diverted to the

eastern coast, by the intervention of the long Island of Kerrera,

distinguished by the ruins at its southern termination of the Danish Fort

Gylen. To the geologist this island is of peculiar interest, as exhibiting

singular junctions of primary, secondary, and trap rocks, and a curious

angular conglomerate or breccia. The circumstance of its being the spot

where King Alexander II. died on his memorable expedition in 1249, and the

place of rendezvous where IIaco of Norway a few years afterwards met his

island chieftains, who, crowding with their galleys to assist hiin in his

descent on the coasts of Scotland, augmented his fleet to 160 sail, will

ever command for Kerrera the attention of the antiquary.

16. Kerrera forms a natural

breakwater to the Bay of Oban, stretching right across, and rendering it a

peculiarly secure ha N en. The bay is not capacious, but is flanked by

nearly parallel wooded rocks, and hemmed in by a higher rocky frontlet, at

the base of which stretch the houses of the village—a long line of neat

buildings, chiefly of two storeys, slated and white-washed, fronting the

water, and presenting a very cheerful and pleasing appearance. On a high,

isolated rock, forming the northern promontory of the bay, girt by

perpendicular precipices, and accessible only on one side, stands Dunolly

Castle, an ivy-clad square keep, an ancient seat of the Macdougals of Lorn,

descendants of the mighty Somerled of the Isles. It is four storeys high ;

but, with the exception of the vaulted dungeon, which is still entire, the

building is now a mere shell. Portions are standing of a wall which,

springing from two opposite angles, ran along the brink of the rock,

enclosing an irregular court. Conspicuous on the face of the rising ground

behind the village, a tasteful Free Church, of light early English

architecture, with a low Norman Tower and pointed spire, after a design by

Mr. Pugin has been lately erected. Nearly opposite the quay a larger and

loftier elevation indicates the Caledonian Hotel, a very commodious and

well-conducted establishment. There are two or three other inns of less

pretensions, and a large proportion of the inhabitants lay themselves out

for the accommodation of lodgers. Oban being a place of great resort in the

season, it is the centre of steam communication on the west coast. One is

hardly prepared, in so remote a corner, to find on some days of the week as

many at times as nine or ten steamers arriving and departing daily. There is

a daily steamer, and, on certain days, as many as three steamers to Glasgow.

One every day, and two on alternate days, to Fort-William and Inverness. One

thrice a week—indeed almost daily—to Staffa and Iona, and round the Island

of Mull, and two every week to Skye, and one to Stornoway. There are besides

two daily coaches, one from Glasgow by Loch Lomond, the other from Inverary.

It is also a favourite sea-bathing quarter and place of summer residence.

Indeed, in the months of July and August, it literally swarms with

strangers. Yet, for sea-bathing it is not well adapted. The water is all

that could be desired, and the beach is pretty good, but the ground along

shore is so confined, that there is little privacy, and there are no bathing

machines. This is, indeed, a general want on the west coast. On the Clyde,

however, the houses often lining the roadway along the bathing ground,

persons can dress and undress in-doors, though it is anything but seemly in

the fair sex in their bathing gear to cross the public way so unconcernedly

as they do. But, indeed, the good people of Oban are singularly behind hand

in meeting the requirements which one would suppose to be indispensable to

the suitable lodgment of their migratory visitors, if not to their own

comfort. The ground-storey of the houses being chiefly occupied with

shops—some of them very good—a peculiar mode of access to the upper floor

prevails, viz., by a passage right through the dwelling, and then up an

outside back stone stair-ease. Thus, and from close contiguity, the back

areas are disagreeably overlooked—in one part of the town the exposure is

heightened by the back-ground being to the water side. Many of the houses

are disgracefully deficient in some of the arrangements essential to the

decencies of life, and preservation of health. A drawback to the well-being

of the place is the limited supply of fresh water, which would probably call

for considerable expense to remedy by artificial contrivances. ' Some more

unexceptionable houses are springing up at the north end of the village. The

furniture is very commonplace, and the apartments plain enough. But the

charges are high. There is no regular butcher or vegetable market; the

supplies are uncertain, and mostly of inferior quality, even the mutton

being ill-fed and scraggy ; and, what will seem more strange, there is but

little fish to be had. A. good deal of salmon and salmon-trout at times, but

only so, and herring; but there is no white fish caught in the bay—what is

exposed for sale, and that in but moderate quantity, being brought chiefly

from Loch Etive. It is rather surprising, considering the steam

communication, that abundant supplies of all eatables should not flow in

from other places for general consumpt. The inns, of course, have their own

source of supply. No mean compensation is abundant and capital dairy

produce, excellent bread, and good groceries. There are some most

respectable shops—among others, a bookseller's, with a tolerable library.

Will it be believed that at this time of day there is no direct post between

Oban and Fort-William—a distance of only forty miles—and that a letter from

the one to the other has to be conveyed round by Inverary, Glasgow, Perth,

and Inverness, and the answer, of course, to make the same extraordinary

roundabout?

17. Yet with these drawbacks

a few weeks can be spent delightfully at Oban. The scenery around is in the

highest degree grand, varied, and beautiful; indeed, the whole features of

the district are remarkable, and it comprises many most noted localities,

while antiquarian remains of great interest abound in the neighbourhood. We

need but enumerate Staffa, Iona, the Sound of Mull, Loch Etive, Loch Creran,

the Pass of Awe, Loch Leven, and Glencoe, Ben Nevis, Ben Cruachan,

Dunstaffnage, and Dunolly, Duart, Ardtornish, Aros, Mingarry, Loch Alline,

Inverlochy, Kilchurn, Gylen, and other castles; Achendown, the Bishop of

Lismore's Palace, and Ardchattan Priory; Berigonium, the site, at least

reputed, of that Pictish capital ; memorials, some of actual monarchy,

others of the almost regal sway of those great princes, the Lords of the

Isles, and rival families of almost equal note. And these are very

accessible from the numerous public conveyances, and the facilities of

transport by boat, besides which, there are very good vehicles kept for

hire. In the immediate, vicinity of Oban there is much to interest. The

heights above command splendid views across the water, the huge sombre

mountains of ,Mull looming above the intervening green and rocky Isle of

Kerrera. From an agreeable promenade in front of the main street, we can

bend our steps along the sides of the bay—though on the north the limits are

somewhat confined by the grounds of Dunolly—or, by an outlet at either

extremity of the street, find our way into the country behind, which is of

that irregular surface characteristic of a trap and conglomerate formation.

From Dunolly the prospect is very fine. The drive to Loch Feochan to the

south is picturesque, while, in the opposite direction, au interval of four

miles brings us to Dunstaffnage, an imposing pile, the residence (though not

the existing edifice) of our early Scottish kings; and by extending the

excursion as far again—from the low rocky eminence on the opposite bay of

Ardnamucknish, the Selma of Ossian, and supposed to indicate the site of

Berigonium—a panorama of mingled mountain, `eater, rock, and plain, is

commanded, of great expanse and most striking character.

Here we may add, that the

powerful Staffa and Iona boats make the circuit of the island of Mull, and

regain Oban about six o'clock in the evening, and that a steamer proceeds to

Fort-William and Corpach in the morning, to bring on the passengers who

leave Inverness the same morning by the canal steamers. On the way tourists

are landed at Ballachulish, where there are conveyances up Glencoe, and they

are picked up again on the return voyage in the evening; or they can, by a

small boat, join the Glasgow boat, which passes on in the evening to Corpach,

where the north-going passengers spend the night, while the northern

travellers on their way south make Oban their resting place.

Having conducted the reader

as far as Oban, we retrace our steps to carry on the descriptions of the

other routes thus far, before proceeding onwards.

To commence with that

FROM GLASGOW TO OBAN AND To

FORT-WILLIAM BY LOCH LOMOND.

18. Though each of the

different routes to the north, by the west coast, possesses its own peculiar

attractions, the palm must be assigned, to that by Loch Lomond and Loch Awe

to Oban, or by Glencoe to Fort-William. But Glencoe can he conveniently

visited on the way from Oban to Fort-William, which itself is not to be

lost, so that Oban is the point to be preferred, there being a coach to Oban

and another to Fort-William, diverging at Tyndrum, the passengers by both

which are conveyed along Loch Lomond by steam. The space to Dumbarton is

traversed sometimes by water, at others by coach, as may suit either

company's arrangements. But the railway from Bowling Bay to Loch Lomond will

doubtless cause a diversion in the stream of passenger traffic.

19. Dumbarton, a few hundred

yards up the river Leven, consists chiefly of a long, crooked, and irregular

street, at the upper end of which a bridge of four arches is thrown across,

and the road to Loch Lomond proceeds on the west side of the stream. The

brick cones of extensive and long-established crown and bottle glass works

still form a prominent feature in the appearance of the town; but owing

chiefly to the repeal of the duties on glass, the manufacture has been

almost given up here. More recent, but already distinguished, ship-building

works in all branches, both timber and iron, also characterise the place;

but the most distinctive feature of all, is its peculiar and renowned

castellated rock, already described in this route. The population in 1841

was 4453. The town was made a royal burgh in 1222 by Alexander II. A remnant

of privileges, much more extensive, is still enjoyed in immunity by the

burgesses, from dues at the Broomielaw and every other port belonging to

Glasgow, with the right of free navigation of the Clyde. In former times the

space round the Castle would seem to have been under water at full tide.

Besides steamers direct several times a-day to and from Glasgow, and twice

a-day to and from Greenock, there are ferry-boats out from Dumbarton at any

hour to meet the steamers.

20. The Leven is, in itself,

a clear winding stream, known to fame by its connexion with the name of

Smollett, whose family residence, Bonhill (now Messrs. Turnbull), is about

halfway between the Clyde and Loch Lomond. A monument has been erected. to

his memory in the village of Renton, a round column on a square die; but it

is shamefully neglected, the tablet being left broken and defaced. He was

born in the old farm-house of Dalquhurn, taken down several years ago. It

stood on the opposite side of the road to the monument, and at the south end

of the village. On either side of the valley the ground rises in continuous

and very gentle slopes, cultivated to the top, with a large quantity of wood

interspersed. Amid these peaceful scenes the spirit of trade has found a

local habitation—numerous public works for bleaching, dyeing, calico

printing, and the manufacture of pyroligneous acid, or white vinegar, being

embowered along the river banks, the workmen belonging to which inhabit the

considerable villages of Renton and Alexandria on the west, and Bonhill on

the east side of the river. Various country seats fill up the fertile and

populous valley, as Cordale House (Stirling), Levengrove (Dixon),

Strathleven (Ewing), Levenbank (Stuart), &c. Nearing the Loch, Tillichewen

Castle (William Campbell, Esq., one of the great Glasgow merchants), a

handsome Gothic structure, is passed, and on the opposite side of the

valley, Balloch Castle (— Stott) shows itself above the foliage. Omnibuses

ply from Dumbarton to the Loch Lomond steamers, and to the Suspension Bridge

at Balloch, at the foot of the lake—soon to be superseded by the railway

above alluded to, in progress, to Bowling Bay, near Port Dunglas on the

Clyde, whence it is eventually to be carried on to Glasgow. The line has

been leased by Messrs. G. & T. Burns, the well-known and spirited steam-boat

proprietors.

21. Loch Lomond, "the lake

full of islands," is unquestionably the pride of Scottish lakes, from its

extent, its numerous islands, and the varied character of its scenery. At

its lowest ex- tremity, where it insinuates its waters into the vale of

Leven, it is for a space quite narrow ; it then expands on either hand, but

especially on the east side, and attains in some places a breadth of seven

or eight miles, and measuring thirty miles in length. Its banks again

approach towards each other, and thence to its termination the lake, winding

among the projecting arms of primitive mountains, and slightly altering at

intervals its general bearings, alternately contracts and dilates its

surface, as it meets and wheels round the impending headlands, among which

it at last loses itself in a narrow, prolonged stripe of water. The

mountains, in general, gradually increase in height, steepness, and

irregularity of surface towards the head of the lake. Those on the west are

intersected by successive glens, as Fruin, Finlass, Luss, Douglas, Tarbet,

and Sloy. The opposite mountains are more unbroken. Numerous little bays

indent the shores, their bounding promontories consisting at the lower end

of flat alluvial deposits, but towards the upper parts of the lake passing

into inclined rocky slopes and abrupt acclivities. At the lower extremity

also, there are large tracts of arable ground ; while above Luss they occur

only at intervals in the mouth of the glens, at the bottom of ravines, or in

open spaces created by the partial receding of the hills. Interrupted masses

and zones of wood and coppice diversify the face of the hills, oak coppice,

mixed with alder, birch, and hazel, predominating. In the broader part, the

surface of the water is studded with islands of many sizes and various

aspects—flat, sloping, rocky, heathy, cultivated, and wooded, stretching

across the lake in three parallel zones. The islands are about thirty in

number; and of these, ten are of considerable size, as Inchconagan, which is

half a mile long; Inchtavanach and Inchmoan, each three quarters ;

Inchlonaig, a mile ; and Inchmurren (the largest and most southerly) two

miles in length. These two last are used as deer parks by the families of

Luss and Montrose, and it is still the practice to place insane persons and

confirmed drunkards in some of the islands. Several gentlemen's residences,

which encompass the lower end of the lake, are surrounded by richly-wooded

parks, as Batturich Castle (Findlay) on the east side, on the site of the

ancient seat of the Lennox family; and Ross Priory (Mrs. M'Donald Buchanan),

frequently visited by Sir Walter Scott ; and in the opposite direction,

Cameron (Smollett) ; Bel Retira (Campbell) ; Arden (Buchanan) ; and farther

up, Rossdhu (Sir James Colquhoun, Bart.), finely situated on a projecting

promontory; and Camstradden (also Sir J. Colquhoun). An obelisk may be

descried on the south-east, raised to the memory of the celebrated George

Buchanan ; and the banks of the Endrick are immortalized by the sojourn for

many years of Lord Napier of Merchiston, the inventor of logarithms, and the

ancestor of the heroes of Acre and Scinde. The whole tract of country on the

east side of Loch Lomond and Leven belongs to the Duke of Montrose, whose

seat, Buchanan, is situated at some little distance inland, while the west

side, from the Fruin water to Glen Falloch, is, with scarce an exception,

the property of Sir J. Colquhoun. A few miles above Luss, we have to admire

successive mountain slopes, rising one behind another in rugged acclivities,

feathered with oak coppice, and irregular rocky precipices shooting up

above; the ample sides of Ben Lomond, in particular extending north and

south in lengthened slopes, his lofty head—a compressed peak—aspiring to the

clouds ; while towards the head of the lake the towering alps of Arroquhar

and Glen Falloch, with their bulky forms, abrupt sides, peaked summits, and

jagged outlines, terminate the prospect. A couple of steam-boats ply upon

Loch Lomond, and, instead of proceeding to Oban or Fort-William, the tourist

can be conveyed from Glasgow to the head of the lake and back again the same

day, or he may reach Inverary, if not Oban, or the Trosachs, or Aberfoil Inn

; the former by the coach or by cars from Tarbet, the two latter from

Invcrsnaid by cart, for those who, coming first, are first accommodated in

the vehicles at command ; others by ponies, always in readiness, caparisoned

with gentlemen's and side saddles; for, though the road be not macadamized,

it is now-a-days quite a thoroughfare. Indeed, it must be confessed that the

rough cart-track is only fit for little sure-footed highland ponies, which

career along as over a bowling-green. At the worst, if disappointed, a walk

of five miles brings one to the little steamer on Loch Catrine. If hurried,

he will find coaches for Stirling, in waiting, at the further end ; and, if

much pressed, may reach Edinburgh or Glasgow the same night. It must be

observed, that it is proper, if for Loch Catrine, to leave the boat on the

way up at Inversnaid, where, as at Tarbet, Rowardennan, and other spots,

there are excellent inns.

The most interesting portion

of the sail on Loch Lomond, is after rounding the most southerly group of

islands at the west, doubling across to Bahnaha on the east, then recrossing

to Luss on the western shore. Here the spacious bosom of the lake is

encircled by islands of various character, presenting middle distances in

every direction. The eye courses over an extensive circuit. To the south the

ground declines, and the outlines are soft and low, and almost horizontal;

and the aspect of nature fertile in the highest degree. The upper boundaries

are mountainous, lofty, and exceedingly varied. Not a point of the compass

is deficient in interest; the panorama is in every part complete, and in all

splendidly beautiful. Viewed in favourable circumstances, be they a hot and

sultry sun, a breathless air, and cloudless atmosphere, when every object is

resplendent with light, and every leaf pencilled as in a mirror; or a cloudy

day, when the overburthened heavens recline their masses on the mountain

sides, or the restless vapours flit along their surface, and when receding

hollow, and projecting cliff, advancing promontory, and retiring bay, or

mountain-cleaving ravine, in mingled light and shade, are contrasted in

strong relief, it may fairly be questioned whether a Lacustrine expanse, so

magnificent, so lovely, and so entirely perfect, is anywhere to be seen.

22. Ben Lomond has perhaps

been ascended by a greater number of tourists than any other of our Highland

mountains. The general view, however, from its summit cannot compare with

that from many others, there being but few openings through the mass of

mountains which stretch around. But the bird's-eye view of Loch Lomond

itself, as seen from the shoulder of the hill, amply repays the labour of

the ascent,—so remarkably lively and diversified is the aspect of its

bespangling islands, the strong contrast between the general character of

its upper and lower portions, the sinuosities of its shores, the mountains

which overhang its waters, or flank its glens, and the rich blush and

glittering smile of its waving fields and cultivated spots. From opposite

Tarbet, the ascent (here rather steep) generally occupies two hours. At

Rowardennan, opposite Inveruglass, five miles further down the loch, it is

more tedious, but considerably more easy, and this is the route most

commonly followed. The waters of Loch Lomond, like those of Loch Ness, are

said to have risen and been much agitated at the time of the great

earthquake at Lisbon, and on the occurrence of several slight earthquakes

since felt in various parts of Scotland ; their depth in the upper division

of the lake being also in several places, as in the other lake just

mentioned, upwards of a hundred fathoms. It is much less than this towards

the lower or eastern end—a farther distinguishing peculiarity of the

opposite extremities of Loch Lomond.

23. At Luss, where the Rev.

Dr. Stewart, the translator of the Gaelic Bible, officiated, there are slate

quarries. Three miles above Tarbet is a small wooded island called

Inveruglass, and about two miles further, another called Eilan Vhou, on each

of which are the ruins of a stronghold of the family of Macfarlane. In a

vault of the latter, an old man of the name, who died not long ago, lived a

hermit's life for a considerable number of years. Nearly opposite

Inveruglass island, about a mile distant from the lake, are the ruins of

Inversnaid fort, on the way to Loch Catrine, an old military station,

chiefly designed to keep the clan Gregor in check. At Tarbet the mountains

to the west, at the head of Loch Long, present a fantastic appearance, from

which they are known by the name of "The Cobbler and his Wife." The head of

Loch Lomond is eight miles from Tarbet ; and six miles from the latter place

a huge mass of rock will be observed by the road side, in which a small

chamber, secured by a door, has been hewn out to serve as a pulpit to the

minister of Arroquhar, whose duty it is to preach occasionally in this part

of the parish. At the head of the lake is Ardlieu, a good inn. The lake is

succeeded, at its upper extremity, for about two miles and a-half, by a

level tract of meadow and arable ground. Behind the inn, where hardwood,

spruce, and larches occupy the valley, the resemblance to many Swiss scenes

is said to be remarkable. Intermediate behind this and Strathfillan is a

wide elevated valley, called Glen Falloch, rising in undulating slopes,

unadorned save by a few scattered firs, and flanked on the east side by

flattened broadly conical mountains, separated by wide corries. From hence,

the river Falloch descends through a shelving rocky channel. It forms an

obtuse angle with the lake, from the end of which the road, following the

course of the river, inclines to the right, and thus looking back, as we

ascend to the upper portion of Glen Falloch, the bulky mountains at the head

of the lake, separated by deep hollows, are seen disposed in a vast

semicircle, and form a most imposing alpine prospect.

24. Glen Fruin, near the

southern extremity of Loch Lomond, was the scene of a well-known sanguinary

clan conflict (in the commencement of the seventeenth century), which

entailed on the clan Gregor a long series of unexampled persecution and

blood-thirsty cruelty. Before adverting to the particulars of the affray,

which jealous and powerful neighbours succeeded in converting into the

source of a legalised warfare of extermination against this unfortunate

race, in connexion with it the circumstances may be reviewed of a barbarous

incident, which had excited James VI. to very harsh measures against them,

and in all probability induced him to make the battle of Glen Fruin the

signal for every species of oppression and wrong. The act alluded to was of

a nature so revolting as to justify the most rigorous punishment; but it

must be considered, that the MacGregors' share in the transaction was but

secondary; and even in those barbarous days, the spectacle was rare, of

government yielding to those revengeful impulses which among families

perpetuated to future generations a deadly quarrel as an heirloom. Some

young men—Macdonalds from Glencoe, having been found trespassing on the

king's deer-forest of Glen Artney, to the north of Loch Achray, by the

under-forester, Drummond of Drummondernoch, had had their ears cropped for

their offence. Their kinsmen in retaliation slew Drummond, when, by his

majesty's special directions, providing venison for the occasion of Anne of

Denmark's arrival in Scotland ; and, having cut off his head, they repaired

to the house of his sister, Mrs. Stewart of Ardvorlich, on the side of Loch

Earn. Her husband was from home; and Mrs. Stewart, giving . them but a cold

reception, laid only bread and cheese before them. While she was out of the

room, they placed Drummondernoch's bloody head upon the table, with a piece

of the bread and cheese in the mouth. The ghastly sight drove her insane;

and leaving her home, she long wandered in a state of mental aberration

through the mountains; and, to add to the catastrophe, she was soon to

become a mother. The murderers hied them from Ardvorlich to the neighbouring

church of Balquhidder, where the MacGregors, with their chief, laying their

hands on the head of Drummond, swore at the altar to shelter and defend the

authors of the deed. This took place about the year 1590. Letters of fire

and sword were issued against the MacGregors, and they henceforth underwent

the most unrelenting treatment at the hands of their powerful neighbours,

who gladly availed themselves of the countenance of Government to harass

them to the utmost. One of the most active of their enemies was Sir Humphry

Colquhoun of Luss, who directed his persecution against the MacGregors of

Balquhidder. With him, Alexander of Glen Strae, at the head of Loch Ave, was

particularly anxious that a reconciliation should be effected ; and for that

purpose, having solicited a conference, he repaired with two hundred of his

clan to a place appointed in the valley of the Leven. On their return

homewards from the meeting, they were treacherously assaulted in Glen Fruin,

by Luss, with eight hundred of his retainers and neighbours. MacGregor had,

however, been apprised of the meditated attack, and his men were on their

guard. They fought so obstinately as to come off victors in the contest,

slaying two hundred of the name of Colquhoun, besides others of their

opponents, and making many prisoners. A tragic incident, of a peculiar

nature, added seriously to the loss of the discoinfited party, and was very

probably the chief means of the battle of Glen Fruin being followed by such

calamitous consequences to the MacGregors. In the adjoining town of

Dumbarton, the principal part of the youth of the Lennox were being educated

at the time: curiosity had led about eighty of them, hearing of the meeting

of their parents and friends, to repair to the neighbourhood of the scene of

action. It was deemed advisable, when hostilities commenced, to confine them

in a barn. They all fell into the hands of the MacGregors, who, while they

followed up the pursuit, set a guard over them, by whose act, or by some

unfortunate mischance, the building was set on fire, and the poor children

destroyed. A partial representation of all these occurrences was made to the

king (James VI.), and to excite him still more effectually, a procession was

got up of sixty widows, whose husbands had been slain on the occasion,

mounted on white palfreys, and tearing on long poles upwards of two hundred

bloody shirts of the slaughtered Colquhouns. Henceforth the clan Gregor were

treated little better than wild beasts. Their lands were confiscated, their

very name was proscribed; and, being driven to such extremity, they became

notorious for acts of reprisal, and famous as systematic leviers of

black-mail. Their services in Montrose's wars first induced some relaxation

of the enactments against them, but till a much later period they continued

in a peculiar position with the clans around them, and endured, though not

with tame submission, along with chastisement, at times deserved, much

unjust and unmerited persecution.

25. Proceeding northwards we

join the main road from Stirling to Fort-William at Crinlarich, between

eight and nine miles from the head of Loch Lomond, and between three and

four miles from Tyndrum, the first stage. There Ben ,Nlore, with its

associated hill-tops, form a noble group. We are now in Strathfillan, to the

east of which is Glen Dochart, nearly in a line with Loch Tay. At the foot

of Ben More lies Loch-an-Our, and further to the east Loch Dochart.

This locality is memorable

for one of the most remarkable passages in the life of Robert Bruce. After

his defeat at Methven, near Perth, he had endeavoured, with a few hundred

men-at-arms, to find his way into the Argyleshire Highlands, but was

encountered in Strathfillan by a superior body of highlanders under Allaster

Macdougal of Lorn, son-in-law of John, the Red Comyn, whom Bruce had slain

at Dumfries, and consequently his inveterate enemy. The battle field, which

lies immediately below Tyndrum, is still called Dalry, or the King's Field.

The Bruce was obliged to retreat. In covering the rear of his forces at a

narrow pass on the edge of Loch-an-Our, three of Lorn's men, who had by a

short cut got ahead of the king, simultaneously assailed him. While one

seized the bridle, another laid hold of a leg and stirrup, and the third

leapt behind him on the horse's back; but his undaunted presence of mind and

uncommon bodily prowess, enabled him, unhurt, to rid himself of this

formidable superiority of numbers. It is said that the first had his arm

hewn off; and the second was thrown down by the King putting spurs to his

horse. Meantime, having extricated himself from the grasp of his third

assailant, he threw him to the ground, and cleft his skull, and then too

killed his prostrate foe with his sword. "Methinks," said Lorn, addressing

one of his followers, "he resembles Golmae-morn protecting his followers

from Fingal." It was on this occasion that Bruce

"Hardly'scaped with scathe and

scorn,

Left the pledge with conquering Lorn"—

the brooch of his mantle,

which unloosed. This precious relic was lost about the middle of the

seventeenth century, and after passing through various hands, was, after an

interval of nearly 200 years, restored to and preserved in the family of

Lorn. This style of brooch, of a circular form, has a raised centre

cairngorm or other stone, and half a dozen little cylinders projecting from

the outer circlet studded with smaller stones of different hues, and is a

favourite and very beautiful shoulder-fastening for the plaid.

26. About half-way between

Crinlarich and Tyndrum there is a line in the river, called the Pool of St.

Fillan's, which is to this day at times the scene of the observance of a

degrading superstitious rite. At every term day, but chiefly Whitsunday and

Lammas, it was and still is occasionally customary to immerse persons insane

or of weak intellect at sunset. They are then bound hand and foot, and laid

all night in the churchyard of St. Fillan's, within the site of the old

chapel. A heavy stick is laid on each side; round these is warped several

times a rope passing over the patient's breast, and made fast in a knot,

which, if found loosed in the morning, a recovery may be looked for ; if

not, the case is supposed to be desperate.

27. At Tyndrum the roads to

Fort-William and Oban diverge. In the hill-face a lead-mine is wrought, in

which the proportion of silver is considerable. The stretch of country

between CalIander and the Western Sea is, for the most part, almost bare of

trees, but to Dalmally, at the head of Loch Awe, our way lies through a

succession of fine pastoral valleys, flanked by lofty hills, characterized

by their pleasing verdant covering, though not distinguished, except

occasionally, as at the Pass of Leni and Lochearnhead, by any very marked

features. There is a considerable descent to Loch Awe. The inn, churches,

and manses of Dalmally (13 miles from Tyndrum) are delightfully nestled

among trees at the opening of Glenorchy, which leads to the Black Mount. The

churchyard of DalmalIy was the burying-place of the Macgregors, many of

whose memorial stones are still to the fore.

28. Loch Awe is about thirty

miles in length, and varies from one-half to two and a half miles in width.

It discharges its water by the river Awe, which issues from a lateral offset

of the lake, branching off at no great distance from its eastern extremity,

and extending from three to four miles into the valley connecting with Loch

Etive, the outlet being thus somewhat peculiarly close by the main feeding

streams. Ben Cruachan's gigantic bulk occupies the space bounded by the

valley and the portion of the lake to the eastward. Its towering proportions

give quite a distinctive character to this end of Loch Awe, different from

the remainder of the lake, which is bounded by numerous chains of hills of

elongated outline, rising tier above tier, and presenting to the eye a great

expanse of mountainous ground, ascending in a gradual inclination. Ben

Cruachan is the focus of the lofty ranges which line Glen Strae and Loch

Etive. It presents a front of several miles to the river Awe and its parent

offset of the lake, while its huge flanks are of corresponding proportions.

In all points of view, the aspect of this mountain is peculiarly massive,

stately, and imposing. The sloping shores of the lake are well cultivated

and wooded, and the streams which fall into it exhibit many pleasing

cascades. About twenty-four little islets are scattered over Loch Awe,

chiefly towards the eastern extremity, some of them beautifully crowned with

dark, nodding pines. On one of these islands, Inishail, or the Beautiful

Isle, are the ruins of a small nunnery of the Cistertian order; and on

Fraoch Elan (the heather isle), those of a castle, which was granted, in

1267, to Gilbert Macnaughten, by Alexander III. This latter isle was the

Hesperides of the country, and is named also from Fraoch, an adventurous

lover, who, attempting to gratify the wishes of thİ fair Mego for the

delicious fruit of the isle, encountered and destroyed the serpent by which

it was guarded, but fell himself a victim to his temerity.

29. The conjoined waters of

two rivers, descending from the respective, nearly parallel, glens, Strae

and Orchy, disembogue themselves into Loch Awe at its eastern extremity, and

at the base of Ben Cruachan. A spacious tract of meadow ground terminates

the lake; and at the mouth of the river, on a point of land between its

waters and a prolonged sweep of the lake, on a slightly protruding rock,

stands an imposing pile of ruins, those of Kilchurn Castle, or Caolchairn,

the "Castle of the Rock." They compose a square oblong building, with one

truncated angle; and a large square keep, flanked by round, hanging turrets,

occupies one corner. The remaining buildings are of varying elevations ; but

the whole of each side of an uniform height, thus affording at once variety

and simplicity of outline, while the general form is set off by a round

tower at each of three angles. All the exterior, and greater part of the

interior walls are entire ; and thus the castle, as a whole, forms, from its

size, a prominent and striking object. The square tower was built in 1440,

on the site of an old castle of the Macgregors, by Sir Colin Campbell, the

Black Knight of Rhodes, third son of Duncan, lord of Lochow, and founder of

the Breadalbane family,—a man of distinguished character. He acquired by

marriage a considerable portion of the estates of the family of Lorn, and

the territories of his descendants extend, uninterruptedly, for 100 miles

inland from the western sea. One of the best points of view is from the

east—the river and meadow-ground in the fore, and the prolonged waters of

the lake, studded with wooded islands, the back ground. The drive round the

base of Ben Cruachan is singularly fine. The bend of the mountain is skirted

with oak woods, above which its giant sides rise with rapid inclination. On

the other hand, the water is hounded by a chain of richly wooded eminences,

divided into separate islands.

30, The river Awe is hounded

by a narrow stripe of flat ground; but the offset of the lake, which

precedes, occupies the whole of the bottom of the valley. For about a mile

and a half next the river it is not a gunshot across ; beyond this gorge it

widens considerably to the main expanse. At the narrow part of the opposing

hills, the eastern one, the base of Ben Cruachan, rises sufficiently abrupt,

while the western ascends from the brink of the water in an acclivity all

but perpendicular, strewed below with finely powdered alluvium, mixed with

verdure, and terminating at top in a continuous, grim, and furrowed

precipice. Where the arm of the lake widens, the western bank declines in a

lengthened slope, affording an exquisite position for the residence and

grounds of Upper Inverawe, while the opposite one increases in steepness;

and the road, amidst the foliage of clambering birch and oak, skirts the

dark waters, which lie deep and still beneath. This spot is called the Pass

of Awe, or the Brander, and is altogether a piece of magnificent scenery.

The prolonged narrow vista of water, hemmed in by impending precipices, with

the wooded islets at its termination, form a splendid landscape of singular

grandeur, richness, and beauty. At this pass John of Lorn made an

unsuccessful attempt to withstand Bruce's advance into his domains, when the

tide of fortune having turned, he came to pay off old scores. Lorn unwarily

left his enemy an opportunity of attaining a vantage ground, a chosen body

of archers, under James of Douglas, Sir Alexander Fraser, and others, having

ascended the hill face, which led to the discomfiture of the Argyle men with

great slaughter.

The view from the top of Ben

Cruachan is, perhaps, as interesting as is to be obtained from any of our

Highland mountains, offering a peculiar intermixture of land and water in

one section of the panorama, and overlooking a most extensive maze of

mountains in the other.

31. Near the mouth of the Awe

and the ferry at Bunaw on Loch Etive, an extensive iron furnace has been

wrought since the middle of last century, by a Lancashire company, who took

long leases of the adjoining woods for the smelting of English iron ore. On

the opposite side of the river, Inverawe House, belonging to Campbell of

Monzie, lies at the foot of Ben Cruachan, amid sheltering trees. A rude slab

has been erected near the little inn of Taynuilt, commemorative of the

thrill of pride felt even in the remotest localities of our common land in

the name of Nelson.

32. Loch Etive is a beautiful

navigable inlet of the sea, about fifteen miles in length, divided into two

distinct compartments of very different characters at the ferry of Bunaw, Of

the western section, framed by hills comparatively low. the shores

alternately widen and contract, projecting into frequent low promontories.

Wood and heath clothe the high grounds, while their borders are diversified

by cultivated fields. The view up the lake is terminated by intersecting

chains and the far-spreading sides and towering broadly-peaked summit of Ben

Cruachan. But above the ferry, where the waters of the ocean have insinuated

themselves amid the recesses of the towering mountains, stretching from Ben

Cruachan towards Glencoe, the scenery assumes a character of severe and

striking grandeur—a long' vista of bare and noble-looking mountains sinking

sheer upon a sheet of water, which but for the rise and fall of the tide, we

might take for an inland lake. We heartily recommend the tourist to hire a

boat to carry him into the heart of this solitude; and if he will, following

the road on the north side of Loch Etive for a couple of miles downwards,

cross over to Bercaldine House on Loch Creran, and thence proceed to Oban by

the ruins of Bercaldine Castle and by Connel Ferry, he will be much

gratified by the detour. Occasionally a steamer takes a run from Oban up

Loch Etive, and parties ought by all means to avail of any such opportunity.

33. On the north side of Loch

Etive, about midway to Connel Ferry, the ruins of Ardchattan Priory, and the

high-roofed prior's house, still inhabited, both encased with luxuriant ivy

and o'er-canopied by trees, with the rich, ascending, undulating, and wooded

parks behind, merit attention. Ardchattan is a name familiar and interesting

to all acquainted with Highland annals. The Priory was built by Duncan

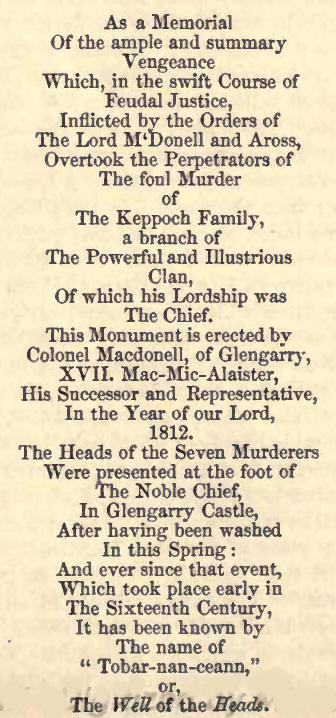

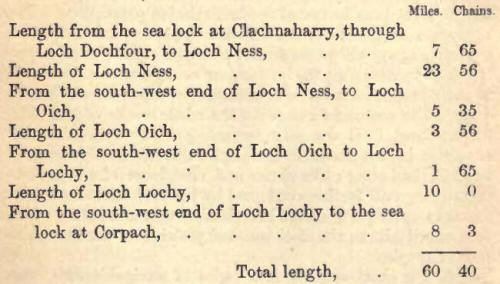

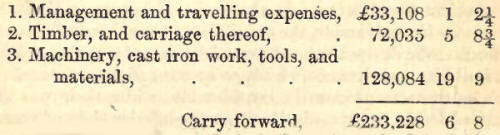

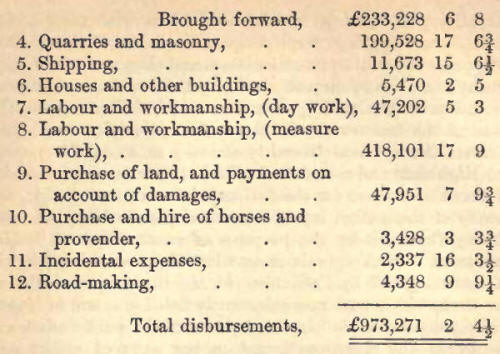

Macdougal, a relative of the Lord of Lorn, in or about the year 1230, and it