|

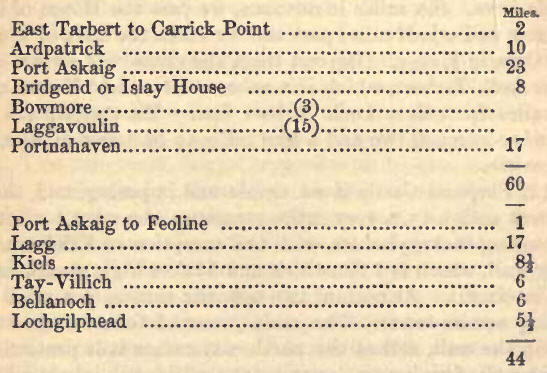

East Tarbert; Isthmus of

Tarbert; West Loch Tarbert, 1.—Sound of Islay; Port Askaig, 2.—General

Description of Islay; Fertility; Productions; Cattle; Fish; Lead and Silver

Mines; Whisky; Inhabitants, their Circumstances and Character; Villages;

Coasts of Islay, 3.—Historical Sketch of the Kings or Lords of the Isles,

4.— Macdonalds of Islay, 5.—Antiquities; Castles and Forts; Macdonald's

Guards; Destruction of the last gang of them; Dunes, or Burghs;

Hiding-Places; Chapels and Crosses; Tombstones; Monumental Stones and

Cairns; Pingwald; Relics, 6.—Hostile Descents on Islay, 7.—Port Askaig to

Bridgend; Islay House, 8. —Sunderland House and Portnahaven, 9—N. W. Coast;

Cave of Saneg More; Wreck of the Exmouth; Princess Polignae's Birthplace;

Loch Gruinart, 10.Bowmore, 11.—Promontory and Bay of Lagean; Mull of Oe;

Cave of Sloc M'haol Doraidh; Port Ellinor; Laggavoulin; Ardmore; 12.—Jura;

General Description; Animals; Antiquities, 13.—Corryvreckan,14.—Colonsay and

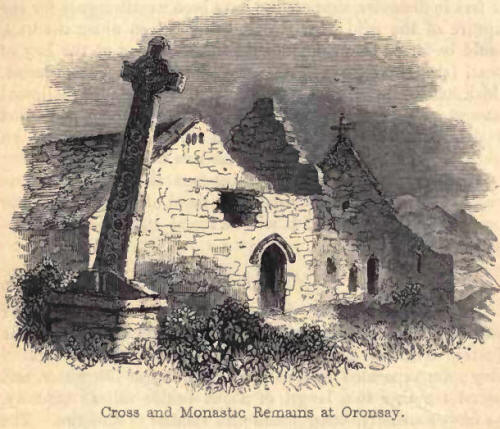

Oronsay; Monastery, and Cross, 15.

1. A REGULAR steam-boat

communication is now established from West Loch Tarbert to Isla and Jura.

The Glasgow and Islay steamer calls twice a-week at Port Askaig. The new

steamer " Islay" arrives at Islay from Glasgow, doubling the Mull of Cantyre,

every Thursday, and sails from Port Askaig in Islay, on Friday, to West

Tarbert, returning to Bowmore the capital of Islay, the same evening.

Generally, too, this boat makes a second voyage to Port Askaig and Tarbert

on Saturday. She leaves for Glasgow, round the Mull of Cantyre, on Monday

afternoon. On landing at East Tarbert, supposing the traveller proceeding

from Loch Fyne, two comfortable inns will be found, situated in a

picturesque, small, crowded, village, built almost entirely on a naked or

barren rock, and manifestly depending more on fishing and other marine

resources than on any agricultural capabilities. In the neighbourhood, to

the eastward, is presented prominently to the stranger's eye, the

interesting ruin of the Castle of Tarbert, the walls of which are still

pretty entire, although large portions have fallen within the last three or

four years; nor will he, on inquiry, be at a loss to have traditions

respecting it rehearsed to him. The traveller bound for Islay leaves East

Tarbert, and proceeds to West Tarbert, a distance of scarcely two miles,

lying across the low isthmus connecting the peninsula of Cantyre with

Knapdale, and which is said to have been formerly protected by two other

castles similar to that at East Tarbert, one in the centre and another at

the western extremity. Magnus Barefoot, of Norway, is reported to have had,

in 1093, a formal cession made to him of the Western Isles, then already

under his sway, by the Scottish monarch; and he is said, on that occasion,

to have caused a galley to be transported with great pomp across the

isthmus, that Cantyre might be brought within the letter of his treaty. At

West Tarbert there is no village, but a pier or quay has been built for the

accommodation of passengers, and the shipping of goods for the steam-packet.

The sail down West Loch Tarbert, which is about ten miles in length, and

bears all the appearance of a peaceful fresh-water lake, is a highly

delightful one. Hills of moderate elevation slope gently from its waters,

rich with woods and cultivated lands, and ornamented with numerous

farmhouses and cottages, and handsome country seats and villas, presenting

scenery peculiarly lively, picturesque, and diversified. The principal

residences are Dippen Cottage, Stonefield House, Grassfield, Kilhammaig, and

Kintarbet, on the east, and Escairt House, Dunmore, and Ardpatrick on the

opposite side, almost all of which belong to families of the name of

Campbell. About midway, on the west, near Stonefield, is the village of

Laggavoulin and Whitehouse Inn, and towards the lower extremity the Clachan

or Kirkton and church of Kilcalmonell, and a little beyond, the hill of

Dunscaith, on which are the traces of a vitrified fort. The sail across to

Port Askaig, in Islay, is about twenty-three miles, On passing Ardpatrick

Point, the appearance of the bleak, sombre, heathy hills of Cantyre and

Argyle is quite uninteresting, and the passenger will feel no reluctance in

being carried away from the coast. In the views in front, the lofty conical

mountains, called the Paps of Jura, form conspicuous objects, picturesque in

the distance, but loosing their interest on a nearer approach. Jura, as the

vessel draws nigh, continues, for the distance of some miles, in seaman's

phrase, to be "kept on board" off the starboard bow and quarter.

ISLAY.

2. The sound of Islay is in

the centre about a mile in width, and is lined by abrupt but not very high

cliffs. It is remarkable for the close correspondence of the opposing

shores, and the great rapidity of its tides; and the navigation is rather

dangerous. On entering the Sound, a strong current is perceptible, which, in

a spring tide, if it happens to be adverse, with any considerable strength

of wind also a-head, will impede very considerably even the power of steam,

while the cross and short sea raised by the current, may even create alarm

to an indifferent sailor. The island of Islay now becoming "tangible to

sight," presents no very interesting or promising appearance. The coast

seems bleak and bluff, without rising into the dignity of real hill or

mountain, and presenting little else than the stunted and heathy vegetation

of Alpine scenery. Here the eye is more relieved by the scene presented in

the offing of the Sound, which seems studded with a lively group of islands,

being Colonsay, with its smaller tributaries. The landing-place of Port

Askaig is soon made, where there is a secure haven and a good pier; and a

tolerably comfortable and commodious inn greets the passenger's arrival.

After the dreariness which threatened the stranger's approach, he is

surprised, on landing at Port Askaig, to find himself at once nestled

securely among well-grown trees and, planting; the face of the hill above

the inn, and some of the adjoining grounds, which rise abruptly from the

sea, being well clad with wood.

3. Islay is about thirty

miles long by twenty-four in extreme breadth. On the south it is deeply

indented by an arm of the sca, called Loch-in-Daal, extending about twelve

miles in length, and terminated by the Point of Rinns on the west, and on

the east by the Moille of Keannouth, or Mull of Oe. This opening has no

great depth of water, but is much resorted to by shipping. About midway, on

the east side, Loch-in-Daal widens out greatly towards the Mull of Oe, which

is opposite the Point of Rinns, forming a capacious bay called Laggan. Port

Askaig is situated about the centre of a high tract of micaceous schist.

From either extremity of this tract, a broad ridge of hills of quartz rocks

extends southward; on the east, to the Mull of Oe, and on the west, to Loch

Groinart, not reaching much further than the head of Loch-in-Daal. The

northern central portion is composed of fine limestone rock, disposed in

rocky eminences or irregular undulations. An ample and fertile alluvial

plain encompasses the upper portion of Loch-in-Daal from Laggan Bay, with

the exception of a stripe of clay-slate, bordering the west side of the loch

and this level ground, which, where not cultivated, is covered with peat,

extends in a broad belt, along the termination of the western hilly range,

to that side of the island. The rest of the adjoining peninsula declines

from the ridge of low hills which skirts the western coast, in fine arable

slopes to the shores of Loch-in-Daal. The northern and western hills are of

moderate height and easy inclination, and are covered with heath, pasture,

and fern. Those on the east are more elevated and rocky. There is a great

variety of soil throughout the island, but it is generally fertile and well

cultivated. Islay, of all the Hebrides, is, beyond comparison, the richest

in natural capabilities, and the most productive. Perhaps more than one half

of its whole surface might be advantageously reduced to regular tillage and

cropping. The facilities for improvement are great ; and in no portion,

probably, of Scotland, have these advantages of late years been more

successfully cultivated; and a steady pursuit of the course of improvement

is still in progress in Islay. This island is celebrated for its breed and

numbers of cattle and horses. It belonged chiefly to Mr. Campbell of Islay

and Shawfield, but is now under the management of trustees, and the estate

is in the market, bond-holders and personal creditors having claims upon it

to the amount of upwards of £700,000. The coast, especially about

Portnahaven, abounds with fish. To the north-west of Port-Askaig, lead-mines

were at one time wrought, and with success. The ore is said to have been

unusually fine, and the late proprietor of Islay could use the rare boast of

having a proportion of his family plate manufactured from silver found on

his own domains. But the mines here have partaken of the fatality that seems

incident to all mining speculations on the north and west coast of Scotland,

and they have, accordingly, been abandoned for many years. Whisky is a great

staple commodity of this island. Its distillation has for some years been

carried on to a very large extent, and there has, of late, been a yearly

revenue of fully £30,000 realised to government from distilleries in this

island alone. More than the half of the grain producing this suin in duties

is imported.

Islay is much exposed to

winds, having little or no wood, except young plantations, and the climate

is moist. The proprietors are generally alive to the importance of extending

among the population the benefits of education. The Gaelic language is

universally spoken throughout the island ; but, as is now the case in less

open parts of the Highlands and islands, it seems rapidly giving way to the

introduction of English. The habits of the population, with respect to

industry and sobriety, are of late years materially improved. The nefarious

and morally destructive trade of illicit distillation used to be carried on

among them to a very great extent; but the introduction of legal

distilleries, and the steady discountenance which this traffic has received

from the present proprietors, have well-nigh put an end to it, and with it

to many of its injurious consequences.

The population amounts to

about 13,000, and the island comprehends three parishes, Killarrow,

Kilchoman, and Kildalton. To these there have been superadded, by the late

Parliamentary grant, three government churches. Three new and substantial

places of worship have also been erected by the Free Church party, since the

Disruption, in 1843. A branch of the National Bank of Scotland has been

established at Bridgend, near Islay House, the princely mansion of the late

proprietor. Islay contains a respectable small town, Bowmore, situated on

the east side, and towards the head of Loch-in-Daal, and distant about three

miles from Islay House, and eleven from Port-Askaig ; and also two or three

villages; as Portnahaven, at the Point of Rinns, the western extremity of

the loch, distant seventeen miles from Islay House; and Port-Ellinor and

Lagganmhoiullin or Laggavoulin, on the east coast, about thirteen and

fifteen miles from Bowmore; and Port-Charlotte on the north-west side of

Loch-in-Daal.

The coasts of Islay consist

chiefly of low rocks and sandy beach. On the west there is hardly any

anchorage, except in Loch Gruinart, an arm of the sea, stretching into the

alluvial deposit which extends across from the head of Loch-in-Deal. There

are several small bays on the east, but they are dangerous of approach, from

sunken rocks. The coasts in general are nowise particularly interesting,

except about Saneg, on the west, where there are several large caves, one

especially, with a labyrinth of passages; and the Mull of Oe, where the

cliffs rise to a great height, and in -which there is another large cave,

that of Sloe Mhaol Doraidh, on the farm of Grastle.

4. Islay is not a little

interesting from the historical associations connected with the remains of

antiquity which it presents, in the ruins of its old castles, forts, and

chapels. It was a chief place of residence of the celebrated Lords, or

rather Kings, of the Isles, and afterwards of a near and powerful branch of

the family of the great Macdonald. The original seat of the Scottish

monarchy was Cantyre, and the capital is supposed to have been in the

immediate vicinity of the site of Campbelltown. In the ninth century it was

removed to Forteviot, near the east end of Strathearn, in Perthshire.

Shortly afterwards, the Western Isles and coasts, which had then become more

exposed to the hostile incursions of the Scandinavian Vikingr, were

completely reduced under the sway of Harold IIarfager, of Denmark. Harold

established a viceroy in the Isle of Man. In the beginning of the twelfth

century, Somerled, a powerful chieftain of Cantyre, married Effrica, a

daughter of Olaus or Olave, the swarthy viceroy or King of Man, a descendant

of Harold Harfager, and assumed the independent sovereignty of Cantyre; to

which he added, by conquest, Argyle and Lorn, with several islands

contiguous thereto and to Cantyre. Somerled was slain in 1164, in an

engagement with Malcolm IV. in Renfrewshire. His possessions on the

mainland, excepting Cantyre, were bestowed on his younger son Dugal, from

whom sprung the Macdougals of Lorn, who are to this day lineally represented

by the family of Dunolly; while the islands and Cantyre descended to

Reginald, his elder son. For more than three centuries Somerled's

descendants held these possessions, at times as independent princes, and at

others as tributaries of Norway, Scotland, and even of England. In the

sixteenth century they continued still troublesome, but not so formidable to

the royal authority. After the battle of the Largs in 1263, in which IIaco

of Norway was defeated, the pretensions of that kingdom were resigned to the

Scottish monarchs, for payment of a subsidy of 100 merks. Angus Og, fifth in

descent from Somerled, entertained Robert Bruce in his flight to Ireland in

his castle of Dunaverty, near the Mull of Cantyre, and afterwards at

Dunnavinhaig, in Isla, and fought under his banner at Bannockburn. Bruce

conferred on the Macdonalds the distinction of holding the post of honour on

the right in battle—the withholding of which at Culloden occasioned a degree

of disaffection on their part, in that dying struggle of the Stuart dynasty.

This Angus's son, John, called by the Dean of the Isles, "the good John of

Isla," had by Amy, great granddaughter of Roderick, son of Reginald, king of

Man, three sons, John, Ronald, and Godfrey; and by subsequent marriage with

Margaret, daughter of Robert Stuart, afterwards Robert II. of Scotland,

other three sons, Donald of the Isles, John Mor the Tainnister, and

Alexander Carrach. It is subject of dispute whether the first family were

lawful issue or illegitimate ; or had merely been set aside, for they were

not called to the chief succession, as a stipulation of the connexion with

the royal family, to whom the others were particularly obnoxious ; or, as

has been conjectured, from the relationship of the parents being thought too

much within the forbidden degrees. The power of John seems to have been

singularly great. By successive grants of Robert Bruce to his father, and of

David II., BaIiol and Robert II., to himself, he appears to have been in

possession or superior of almost the whole western coasts and islands.

Ronald is said to have had the chief rule intrusted to him during his

father's Iifetime; but on his death he delivered the sceptre to Donald,

thereupon called Macdonald, and Donald of the Isles, contrary, it is said,

to the opinion of the men of the Isles. From Ronald, who inherited large

possessions on the mainland of Inverness-shire and in the Long Island

through the death of Ronald Rorison his mother's brother, are descended

Macdonald of Clanranald, by Allan of Moidart, and Macdonell of Glengarry (by

another Donald), rival competitors with Lord Macdonald of Sleat, descendant

of Donald, son of John, for the chieftainship of the clan Coila. The

Macdonalds of Keppoch are sprung from Alexander Carrach. Donald of the Isles

seems to have taken up his residence in the Sound of Mull, while Islay,

holding of him, fell to the share of his brother, John Mor, progenitor of

the Antrim family. By marriage with the sister of Alexander Leslie, he

became entitled to the estates and earldom of Ross, her niece having taken

the veil. Donald, resolved to vindicate his claim, proceeded with a great

force in 1411 to Aberdeenshire, defeating on his way the Mackays at Dingwall,

and burning the town of Inverness. He was encountered at Harlaw by the Earl

of Mar. After a bloody and doubtful contest, both parties retreated.

The inordinate power of these

island princes was gradually broken down by the Scottish monarchs in the

course of the fifteenth and early part of the sixteenth century. On the

death of John, Lord of the Isles and Earl of Ross, grandson of Donald, Hugh

of Sleat, John's nearest brother and his descendants became rightful

representatives of the family, and so continue. Claim to the title of Lord

of the Isles was made by Donald, great-grandson of Hugh of Sleat; but James

V. refused to restore the title, deeming its suppression advisable for the

peace of the country.

5. Towards the end of the

sixteenth century, fierce feuds broke out between the Macdonalds of Islay

and the Macleans of Mull. Sir Laughlan Maclean, in 1598, invaded Islay with

1400 men; but he was successfully opposed, at the head of Loch Gruinart,

lying to the west of the head of Loch-in-Daal, by Sir James Macdonald, the

young chief, his nephew, who had an inferior force of 1000 men; and Maclean

was slain, with a number of his followers. Hereupon the inheritance of the

Macdonals of Islay and Cantyre was gifted to the Earl of Argyle and the

Campbells. Violent struggles ensued between these parties, especially in

1614, 1615, and 1616, when the Macdonalds were finally overpowered, and Sir

James obliged to take refuge in Spain; but he was afterwards received into

favour. The power of the Macdonalds in Islay, having thus passed into the

hands of the Campbells, has never since been recovered, and their sway in

Argyleshire has wholly disappeared.

6. The remains of the

strongholds of the Macdonalds, in Islay are the following. In Loch Finlagan,

a lake about three miles in circumference, three miles from Port Askaig, and

a mile off the road to Loch-in-Daal, on the right hand, on an islet, are the

ruins of their principal castle or palace and chapel ; and on an adjoining

island the Macdonald council held their meetings. There are traces of a

pier, and of the habitations of the guards on the shore. A large stone was,

till no very distant period, to be seen, on which Macdonald stood, when

crowned by the Bishop of Argyle King of the Isles. On an island, in a

similar lake, Loch Guirm, to the west of Loch-in-Deal, are the remains of a

strong square fort, with round corner towers; and towards the heap: of

Loch-in-Deal, on the same side, are vestiges of another dwelling and pier.

Where are thy pristine glories

Finlagan!

The voice of mirth has ceased to ring thy walls,

There Celtic lords and their fair ladies sang

Their songs of joy in Great Macdonald's halls.

And where true knights, the flower of chivalry,

Oft met their chiefs in scenes of revelry—

All, all are gone and left thee to repose,

Since a new race and measures new arose.

The Macdonalds had a body

guard of 500 men, of whose quarters there are marks still to be seen on the

banks of the loch. For their personal services they had lands, the produce

of which fed and clothed them. They were formed into two divisions. The

first was called Ceatharnaich, and composed of the very tallest and

strongest of the islanders. Of these, sixteen, called Buannachan, constantly

attended their lord wheresoever he went, even in his rural walks, and one of

them denominated "Gille 'shiabadh dealt" headed the party. This piece of

honourable distinction was conferred upon him on account of his feet being

of such size and form as, in his progress, to cover the greatest extent of

ground, and to shake the dew from the grass preparatory to its being trodden

by his master. These Buannachan enjoyed certain privileges, which rendered

them particularly obnoxious to their countrymen. The last gang of them was

destroyed in the following manner by one Macphail in the Rings:—Seeing

Macdonald and his men coming, he set about splitting the trunk of a tree, in

which he had partly succeeded by the time they had reached. He requested the

visitors to lend a hand. So, eight on each side, they took hold of the

partially severed splits; on doing which Macphu . removed the wedges which

had kept open the slit, which now cloyed on their fingers, holding them hard

and fast in the rustic man-trap. Macphail and his three sons equipped

themselves from the armour of their captives, compelled them to eat a lusty

dinner, and then beheaded them, leaving their master to return in safety.

Macphail and his sons took shelter in Ireland. The other division of these

500 were called Gillean-glasa, and their post was within the outer walls of

their fastnesses. These forms were so constructed that the Gillean-glasa

might fight in the outer breach, whilst their lords, together with their

guests, were enjoying themselves in security within the walls and especially

within the impenetrable fortifications of Finlagan. [Descriptive and

Historical Sketches of Islay, by William Macdonald, A.M., M.D.]

On French Isle, in the Sound,

are the ruins of Claig Castle, a square tower, defended by a deep ditch,

which at once served as a prison and a protection to the passage. At

Laggavoulin Bay, an inlet on the east coast, and on the opposite side to the

village, on a large peninsular rock, stands part of the walls of a round

substantial stone burgh or tower, protected on the land side by a thick

earthen mound. It is called Dun Naomhaig, or Dunnivaig (such is Gaelic

orthography). There are ruins of several houses beyond the mound, separated

from the main building by a strong wall. This may have been a Danish

structure, subsequently used by the Macdonalds, and it was one of their

strongest naval stations. There are remains of several such strongholds in

the same quarter. The ruins of one are to be seen on an inland hill, Dun

Borreraig, with walls twelve feet thick, and fifty-two feet in diameter

inside, and having a stone seat two feet high round the area. As usual,

there is a gallery in the midst of the wall. Another had occupied the summit

of Dun Aidh, a large, high, and almost inaccessible rock near the Mull.

Between Loch Guirm and Saneg, and south of Loch Gruinart, at Dun Bheolain (Vollan),

there are a series of rocks, projecting one behind another into the sea,

with precipitous seaward fronts, and defended on the land side by cross

dykes; and in the neighbourhood numerous small pits in the earth, of a size

to admit of a single person seated. These are covered by fiat stones, which

were concealed by sods.

There are also several ruins

of chapels and places of worship in Islay, as in many other islands. The

names of fourteen founded by the Lords of the Isles might be enumerated.

Indeed, most of the names, especially of parishes of the west coast, have

some old ecclesiastical allusion. In the ancient burying-ground of Kildalton,

a few miles south-west of the entrance of the Sound, are two large, but

clumsily sculptured stone crosses. In this quarter, near the Bay of Knock,

distinguished by a high Sugarloaf-shaped hill, are two large upright

flag-stones, called the two stones of Islay, reputed to mark the

burying-place of Yula, a Danish princess, who gives the island its name. In

the churchyard of Killarrow, near Bowmore, there was a prostrate column,

rudely sculptured; and, among others, two gravestones, one with the figure

of a warrior, habited in a sort of tunic reaching to the knees, and a

conical head-dress. His hand holds a sword, and by his side is a dirk. The

decoration of the other is a large sword, surrounded by a wreath of leaves ;

and at one end the figures of three animals. This column has been removed

from its resting-place and set up in the centre of a battery erected near

Islay House some years ago. Monumental stones, as well as cairns and

barrows, occur elsewhere; and there is said to be a specimen of a circular

mound with successive terraces, resembling the tynewalds, or judgment-seats,

of the Isle of Man, and almost unique in the Western Islands. Stone and

brass hatchet-shaped weapons or celts, elf-shots or flint arrow-heads, and

brass fibulae, have been frequently dug up.

7. In later days, Islay was

distinguished by a visit from the French squadron under Admiral Thurot, in

1760, which put in in distress for provisions, for which, however, the

Admiral honourably paid. Again, in the autumn of 1778, the notorious Paul

Jones made a descent here. In the Sound he captured the West Tarbert and

Islay packet. Among the passengers was a Major Campbell, a native of the

island, just returned from India where he had realised an independence, the

bulk of which he had with him in gold and valuables, and the luckless

officer was reduced in a moment from affluence to comparative penury. Of

much more recent occurrence was the appearance in Loch-in-Daal on 4th

October 1813, of an American privateer of twenty-six guns, with a crew of

260 men. "The True Blooded Yankee," by which a crowd of merchant vessels

which, happeriod to be lying in Port Charlotte was rifled, and then set on

fire, occasioning a loss estimated at some hundred thousand pounds. It is

some satisfaction to know that this piratically named craft was subsequently

made prize of and condemned.

The genuine Islaymen, are to

this day remarkable for size and goodliness of person, and the body of

clansmen who accompanied Islay to welcome her Majesty at Inverary in 1847

attracted peculiar notice.

8. We proceed now to conduct

the reader through the island. Leaving the inn of Port Askaig, the road

winds up a ravine or gully, for nearly a mile, exciting hopes that the

wayfarer has really been conducted to fairy-land. These, however, soon

cease; for, on making the summit of this ravine, the country again becomes

bare and exposed, but presenting an appearance of abundant and rich

vegetation, with marks of successful culture around. After traversing four

or five miles, the country assumes a still improved appearance. The

government church and manse of Kilmenny are passed on the left, and after

about four miles more travelling, we reach the inn of Bridgend. Previous to

this, however, the sea is seen on the opposite coast of Islay, flowing into

the spacious Bay of Lochin-Daal, which forms a very interesting and lively

object, running straight inward from the Irish Channel, a distance, from the

Point of the Rinns to Islay House, of at least twelve or fourteen miles.

Before arriving at Bridgend, the appearance of the country, particularly to

the left, strikes a stranger as rich, beautiful, and interesting, varied in

surface, and forming principally a strath or glen, watered by a considerable

stream, interspersed with thriving plantations of larch and other trees.

From Bridgend, a pretty good view is had of Islay House, or, as it is here

called by the natives, The White JIouse. This mansion is surrounded,

especially in front, by a very extensive and level lawn, with the ground

gently rising, and well wooded behind. The house is on a large and princely

scale, the pleasure-grounds and gardens extensive and embellished. Towards

Bridgend, to the left of Islay House, stood formerly the village of

Killarrow.

From Bridgend the touirst may

easily make a short and interesting excursion to .Loch Finlagan, which lies

north-east from Islay House about five miles, and on an island in which are

to be seen the ruins, as already mentioned, of a principal residence of the

Kings or Lords of the Isles. Between it and Islay House lies the place

Eallabus, until lately the residence of the factor of Islay; an interesting

and beautiful locality, and the native spot of John Crawfurd, Esq., the

author of a "History of the Indian Archipelago," the "Embassy to Ava," &c.

9. If it be the object of the

tourist to have a full local acquaintance with the fertile and interesting

Island of Islay, certainly the queen of the Hebrides, we would recommend his

taking, first, the road along the north side of Loch-in-Daal to the Rinns,

or the Point of Islay stretching to the south-west. After passing along

rather a bleak tract for two or three miles, he arrives at the Bay of

Sunderland, bending gently inwards from the direct course of Loch-in-Daal;

and passing along the beach for upwards of a mile, be may turn to the right,

and, after a gentle ascent, will come unexpectedly in view of the

mansion-house and grounds of Sunderland, (Mac Ewen, Esq.); and, if

interested in rural and agricultural pursuits, he will reflect with pleasure

that the beautiful scene now before him was, not many years ago, a bleak,

uninteresting, and unpromising expanse of dry moss and heather, with

scarcely even a spot of green sward on which to rest the eye. Returning

again to the road, the traveller still proceeds close to the sea-shore, and

along a fertile and tolerably cultivated stretch of country, passes the new

and thriving village of Port Charlotte, and, some five or six miles onward,

the road cuts across the extreme promontory of this part of the island,

conveying him to the village of Portnahaven, a celebrated cod-fishing

station, on the property of Mr. Mac Ewen of Sunderland, and containing about

sixty slated houses, very picturesquely situated on a rocky nook of a wild

bay, which is protected by an island in the offing from the stern blasts of

the west. On this island a lighthouse has been built ; and, perhaps no

station on the whole coast of Scotland, if we except Cape Wrath, more loudly

demanded this preservative measure to the shipping interests and to human

life.

10. Leaving Portnahaven, the

traveller can by a good road proceed along the north-west coast of the

island, where be will find a fertile country, well cultivated, till he come

to the church of Kilchuman; and, leaving it on the right, he had better

still adhere to the line of the coast. Approaching Kilchuman, and

afterwards, for the distance of two or three miles, the soil becomes sandy

and arid; but, removed from the immediate sea coast, it is mingled with a

good fertile loam, which has been improved, on the best principles of

husbandry, by the proprietor of Sunderland, whose lands stretch downwards in

this direction. Following the coast from Kilchuman, its appearance is

striking and grand: perpendicular rugged rocks rising from the ocean, and

rent by numerous chasms, among which are a series of curious caverns, arrest

the attention.

Within the cave of Saneymore,

the access to which is somewhat difficult, there is an inner cave, opening

into successive passages, and narrow galleries with intermediate chambers,

amidst which the reverberation of a gun-shot is quite overpowering, and the

cadence of the notes of the bagpipe, varies from the faintest murmur to

deafening loudness. It was near Sancymore that the tragical shipwreck of the

emigrant brig Exmouth, from Londonderry for Quebec, occurred, on 27th April

1847, when all the passengers, 240 in number, with all the crew excepting

three, found a watery grave. The appearance of the shore after the storm,

strewed with fragments of wreck and dead bodies, and mangled limbs, is

described to have been appalling and heart-rending beyond conception.

The reader may be interested

to know that Ardnave, a handsome residence beyond Saneg, is the birthplace,

we believe, at least the paternal residence, of Miss Campbell, Lady of

Polignac, sometime prime minister of France.

Loch Gruinart, an arm of the

sea, which the traveller will meet in his progress, is celebrated by Dean

11lonro, in his account of the Hebrides, for the number of seals which were

caught or slain on the sand-banks which the recess of the tide here leaves

exposed ; but the sport of seal-catching here has long ago been forgotten.

The sands of Gruinart are

celebrated in the traditional lore of the islanders, for the bloody conflict

already mentioned, fought in 1598, between the Macdonalds and Macleans. The

east side of Loch Gruinart presents merely a low sandy expanse of coast,

after which it rises gradually into higher and bleaker hills towards the

Sound of Islay and Port Askaig. From the head of the loch, a walk of four or

five miles across the country conducts to Bridgend. The route here

described, from Bridgend till returning there, might be accomplished easily

in a long summer or autumn day, with the help of a good Islay pony, and an

equally hardy and active guide.

11. After resting at

Bridgend, proceed we now to the metropolis of Is]ay, the village of Bowmore,

lying about three miles south-west from Bridgend, and on the shore of Loch-inDaal

; a continuation of tile-roofed cottages extending partially along the shore

from Bridgend. Bowmore is of considerable size, containing a population of

from 900 to 1200 inhabitants. It was commenced in 1768, and is judiciously

and r agularly planned ; but the plan has been but indifferently observed,

houses being permitted to be erected of any size, shape, or material, suited

to the means and views of the builder. A principal street, ascending a

pretty steep hill, is terminated at the west by the school-house. From the

hill behind, an extensive and beautiful view is obtained of Loch-in-Daal in

all its expanse, of Islay House and the adjacent grounds in the distance, of

the Rinns, and the district of Islay already described. Another wide and

also ascending street crosses this at right angles, beginning at the quay,

which is a substantial edifice, admitting common coasting vessels to load

and unload, and terminates at the summit by the village and parish church; a

respectable building, of a circular form, surmounted by a neat spire. A

third street runs parallel to the one first described, along which the

houses present so poor an appearance as to leave the popular designation it

has received in the village, of the "Beggar Row," far from being a misnomer.

12. Leaving Bowmore, the

traveller proceeds southward, passing the church on his left, and continues

to ascend by a gentle acclivity for about a mile. The road now slopes gently

downwards, and inclines towards the wide expansive Bay of Laggan. But at the

summit mentioned, a good view is had of the bleak promontory—a dead and dull

mass—dividing Loch-in-Daal from the Bay of Laggan, tapering to the west, and

terminating in a rocky point. On descending along the road to the Bay of

Laggan, the traveller is struck with the appearance of its ample and

spacious waters, bounded partly by rocks of rugged aspect and moderate

height, and skirted all along its basis by a broad belt of beautiful sand.

In this hay many shipwrecks have occurred, by seamen mistaking it, and

bearing up for it, instead of Loch-in-Daal. Leaving the level of the bay, a

gentle acclivity is ascended, and the scene becomes less interesting, though

still a pleasing variety of pasture and tillage is seen scattered around. On

his right, the traveller has a considerable portion of the island cut off.

This is the bluff Point of Keannouth, or, as it is more frequently called,

the Oe. If interested in antiquarian pursuits, it may repay his labours here

to turn off, obtaining a guide to bring him to the old castle or fort of Dun

Aidh, built upon the extreme summit of the rock forming the western

extremity of the Point of Oe. The scene is impressive and grand. The castle

or fort is quite a ruin, but may be seen to have been a place of very

singular strength in its day. The cave of Stoc Mhaol Doraidh, on the farm of

Grastle near the Oe, is only accessible by boat, and with favourable

weather. A huge pillar of rock guards the outer entrance, which is an

archway in a wall of rock. From the space within, a low opening, only

admitting a small boat, ushers into a spacious apartment with two recesses,

all watered by the sea. Our road soon now attains the sea-shore, at a

spacious bay, forming a safe and good anchorage, with a much better outlet

than Loch-in-Daal, and well sheltered, especially from the north and west.

Here a new village has been in progress for a few years back, named Port

Ellinor, in compliment to Lady Ellinor Campbell of Islay.

A mile or two farther on, the

road arrives at the small village of Laggavoulin, near which is the parish

church of Kildalton, and the clergyman's residence, very picturesquely

situated beside a rocky inlet of the sea coast, opposite to the remains of

the round tower or burgh Dunnivaig. From Port Ellinor to Laggavoulin, the

country presents a well cultivated and fertile aspect, and a surface

obviously susceptible of great and advantageous agricultural improvements.

Leaving the village just mentioned, the road keeps along the shore for two

or three miles farther, when the country assumes rather a pastoral than an

agricultural appearance, and is partially studded with birch, hazel, and

other copsewood. Turning down into a small beautifully wooded promontory,

forming one side of a still, peaceful inlet of the sea, is seen an elegant

and spacious cottage, built by Mr. Campbell of Islay. Onwards a mile or two

is the farm and house of Ardmore. From this quarter of the island, a good

view is presented of the opposite coast of Cantyre—towards Campbelltown, and

the Mull of Cantyre. In clear weather also, the Irish coast is discernible

to the naked eye. From Ardmore, round the coast to Port Askaig, there is

scarcely any object of interest to reward the toil of exploring it. But if

it suits the tourist's time and purpose better than returning by Bowmore and

Bridgend to Port Askaig, he can easily make the latter place, from

Laggavoulin or Ardmore, in the course of one day, though at the expense of

some bodily fatigue.

JURA.

13. This island is about

thirty miles long, and tapers from the south, where it is seven or eight

miles wide, till at the northern extremity it becomes only about two miles

broad. It is, with the exception of a narrow border on the east side, a

rugged and barren region. A series of steep and lofty mountains of quartz

rock extend northwards from the Sound, shooting into four conical peaks,

three of which, more elevated than the others, are, from their peculiar

shape, called the Paps of Jura; the highest being about 2500 feet. These

are, on their lower sides, covered with dusky heath, and higher up with

broken fragments of stone and masses of rock; and with the exception of the

embedding moss around these, they are there almost bare of vegetation. The

west side is altogether wild and rugged, unfit for cultivation, and

uninhabited. On the cast the shore is low, and succeeded by gentle slopes,

extending to the base of the hills. This coast is indented by several bays,

and shoots out various points of land; thus presenting a somewhat pleasing

appearance. It is intersected by numerous rapid streams, and the soil by the

shore is poor and stony—on the declivity more or less clayey and spouty.

There are two fine harbours on the east side, the southernmost protected by

several small islands at the mouth: the entrance of the other is between two

projecting points of land. Loch Tarbert, a long arm of the sea, at the

middle of the west side, almost intersects the island. This inlet abounds

with a variety of shell-fish. On the same coast there are quantities of fine

sand, used in the manufacture of glass. The population does not exceed 800.

The breeds of cattle and horses are hardy, but more diminutive than those of

Islay. Though the name of the island is significant of the abundance of deer

on it—Jura, from Dhuira, or Dera—yet these animals are now not numerous,

eagles and goats being the chief tenants of its rocky solitudes.

Several tumuli, remains of

Danish burghs, and similar antiquities, are to be met with ; and in one or

two places there are traces along the declivities of a wall that had been

about 41 feet high, with, at its lower termination, a deep pit about 12 feet

in diameter, supposed to have been a contrivance for the capture of the wild

boar, which, being driven along the wall, would be forced into the pit. At

the north end of the Bay of Small Isles there are remains of a considerable

encampment, which has consisted of three ellipses of some depth, hollowed

out and embanked, and protected on one side by a triple line of defence with

deep ditches, and by regular bastions on another, and having a mount of some

size at the east end.

14. Corryvreckan, the strait

between the northern extremity of Jura and the mountainous island of Scarba,

possesses a wide-spread notoriety. It will be found described p. 76.

COLONSAY AND ORONSAY.

15. These islands are

distinguished, next to Iona, by the most extensive remains of religious

edifices of any of the Western Islands. They lie about north-west of the

Sound of Islay; are separated by a narrow strait, dry at low water, and

extend together to a length of about twelve miles; Oronsay, the most

southerly, being much the smaller of the two. The Islands are named after

St. Columba, and his companion St. Oran. The hills are rugged, but not high,

and the pasture on the low grounds, particularly to the south, is remarkably

rich. Rabbits abound in these islands. The population may amount to about

600. A Culdee establishment was founded in Colonsay, called after St. Oran

Killouran. There exist on Oronsay the ruins, still pretty entire of a priory

or a monastery of either Cistertian or St. Augustine monks, of which the

abbey stood in Colonsay, but it has been completely destroyed. Both were

founded by the Lords of the Isles about the middle of the fourteenth

century. The priory measures sixty by eighteen feet. Adjoining it is a

cloister of a peculiar form. It forms a square of forty feet externally, and

twenty eight within. On each of two opposite sides are seven low arches,

composed of two thin stones for columns, with two others forming, an acute

angle, and resting on two flat stones placed on the top of the upright ones.

The only remaining side has five small round arches. In a side chapel is the

figured tomb of an abbot, Macdufie, anno 1539, and also a stone with a stag,

dogs, and a ship sculptured upon it. A large and very elegant stone cross

stands beside these buildings, and within the priory are various tombstones

of warriors and others. Several tumuli exist in Oronsay; and on Colonsay are

the ruins of several chapels, and within the memory of man those of St.

Oran's cell were discernible, and there are also some monumental stones.

|