|

General Character of

Sutherlandshire, 1.—Muir of Tulloch; Kyle of Sutherland Cattle Trysts, 2.—Strath

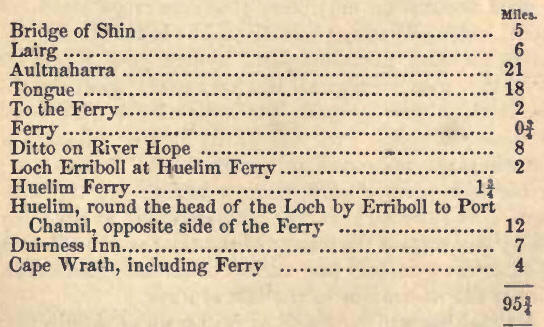

Shin; Achany; Linn of Shin; Strathfleet; Mail Phaetons to Loch Slim, 3.—Ben

Clibrick; the Crank; Line of policy observed in Sutherland-shire;

Expenditure on improvements; Suthrrlandshire Inns; Social state of the

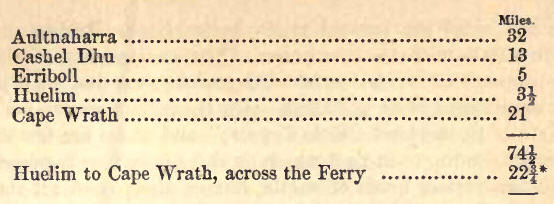

Peasantry; Projected modifications of system; Progress of Agriculture,

4.—Natural features of the county, 5.—Aultnaharra to Erriboll; Strathmore;

Ben Hope, 6.—Rob Donn, the Poet; Duncan Ban Maclntyre; Gaelic Poetry, 7.—Dun

Dornadilla, 8.—Strathnaver; Depopulation, 9.—Ben Loyal; Loch Loyal; Lochs

Craggy and Slam; Kyle and House of Tongue; Kirkiboll Village, 10.—The Main;

Roads, 11.—Ferries; Chain Boats, 12.—Ben and Loch Hope; Camusinduin Bay;

Loch Erriboll; Rispond, 13.—Cave of Smoo, or Uaigh Mhore; Cascade;

Superstitions, 14.—Farout Head; Balna Kiel-house; Rob Bonn's Grave;

Tombstone of Donald Mac Morchie-ic-coin-mhair; Shipwreck; Cave of

Poul-a-Ghloup, 15.—Cape Wrath; Lighthouse; View from Cape Wrath, 16.

1. SUTHERLAND possesses

several peculiar features, and is a county comparatively little known. Its

fastnesses have been but recently rendered accessible by connected lines of

road. Practised visitors of the highlands have found their way of late in

considerable numbers to Sutherlandshire; but to the mass of tourists it is

yet a terra incognita. As it presents all the freshness of novelty, though

remote, its wild scenery, however, will doubtless soon attract the attention

of the travelling public in general. A great expanse of heathy, mossy, and

treeless wastes occupies the bulk of the country, and the habitations of men

are but very sparingly indeed scattered over its surface. Lonely wildness is

thus a decided characteristic; but verdant straths, and splendid lakes cheer

the traveller in his progress, and the lofty and noble forms of the

mountains command his admiration, while the coasts, and the numerous

salt-water lochs which break in and lose themselves among the precipitous

mountains, present every variety of maritime landscape.

2. Proceeding westward along

the Kyle of Dornoch from Bonar Bridge, the tourist passes the Muir of

Tulloch, within half-a-mile of Bonar, where was fought a "cruel battell"

between a party of Danes and the men of Sutherland, in the eleventh century;

and many tumuli and cairns still mark where lie the remains of the fallen

combatants. The heights, till we reach Portinlick, where there is a ferry

across the Kyle, are, like the hill sides for several miles below Bonar

Bridge, on the north side—with the exception of the small estate of Creich,

the property of Mr. Gilchrist of Ospisdale—covered with thriving plantations

of fir and larch. On the hill above are held the Kyle of Sutherland Cattle

Trysts ;" and there are few scenes more enlivening than that which on these

occasions is presented, in the numerous herds of cattle, horses, sheep, and

all sorts of four-footed animals; the almost equally numerous bipeds of all

degrees, in the persons of drovers, gentlemen farmers, cottars, and

herdsmen, and the hundred and one party-coloured tents for refreshments,

formed, some of old field-tents, much the worse for the wear, others of the

gaily chequered home made blanket, and many of a nondescript patchwork,

composed of a mixture of all sorts of stuffs, which, though not exactly fit

to bear part in a field-day exhibition, still, when viewed from a little

distance, add to the general effect of the scene, and lend to it not a

little the resemblance of a martial display. Both the farmer and the drover

may be detected at a glance by their calculating faces; having, however,

this material difference generally—that the subject of the poor farmer's

calculation is the amount of loss he sustains, and according to the result

is his countenance proportionally elongated; whilst the drover, whose whole

trade is gambling, uniformly calculates his prospects of gain. The lowing of

cattle, the neighing of horses, the bleating of sheep, and, above all, the

peculiar shout of the herdsmen, who have enough to do to check the excursive

propensities of their four-footed charge, help to render the scene

altogether one of the most exhilarating description.

3. About two miles beyond

Portinlick is the Bridge of Shin, across the river of that name, and five

miles from Bonar. The road here divides, one branch leading directly west,

to Assynt, the other northwards, to Lairg. This latter road proceeds along

the west bank of the river of Shin, [Another road also conducts to Lairg, on

the east side of the river, but the first is preferable, in so far as it

proceeds through the woods and by the mansion of Achany, and close by the

river, while the other commands views from above of these and of Strathoikel,

and on the former the river has to be crossed at a ford.] through a narrow

strath of heathy slopes rising immediately from the water, and to some

height. On the west side lies the well-wooded and now highly improved and

beautiful estate of Achany (James Matheson, Esq. M.P.), having a commodious

mansion-house. Adjoining to it, on Loch Shin side, is the pretty property of

Gruids, now also acquired by him, and also between and the Oikel, the fine

estate of Rosehall, forming together a very nice Highland estate. At a

distance of six miles, the western road crosses the river at a ford near the

village of Lairg, which stands on the east bank, and where there is also a

coble and piers on the river. On leaving the river the traveller passes the

Linn of Shin, where, as the name implies, there is a waterfall, more

remarkable, however, as a salmon-leap than as a cascade. The salmon

proceeding up the river may here be seen making many unsuccessful attempts

to surmount the ledge of rock that forms the fall, which is about eight or

nine feet in height, and many, by dint of great perseverance and strength,

do succeed.

From the Ferry of Lairg a

road leads westerly, which, at a distance of eight miles, over very dreary

elevated moorland ground, joins, at Rosehall, the Assynt road from the

Bridge of Shin. The few miserable huts passed at the commencement, with

their scanty shapeless patches of cultivated ground partially encircled by

caricature dykes of multiformed stones, and most precarious-looking

formation, are very unpromising indications of the discomforts and poverty

of the people. Another road, crossing the hill behind Lairg, proceeds

eastward through Strathfleet, by the valuable farm of Morvich, to the Mound,

fourteen miles distant, where it joins the great north road. In the lower

part of Strathflcet there is a considerable collection of smaller tenants,

the improvements made by whom are very pleasing, and a substantial earnest

of what may, and we doubt not will, soon be done, much more extensively than

hitherto in that direction. Mail phaetons, as has been already mentioned,

traverse the county from Golspie to Tongue, and to Loch Inver and Scourie,

and will, it is to be hoped, be speedily placed on the road from the latter

place to Duirness and Tongue, and the communication round the coast be thus

completed. At Lairg there is an excellent new inn, which commands a sweet

view of the lower section of Loch Shin, about which there is a good deal of

cultivated land. This lake is about eighteen or twenty miles in length,

stretching to the north-west, and from one to two miles broad, surrounded by

very low hills, rising in lengthened very slightly-inclined slopes. The

inn-keeper at Lairg used to have the privilege of permitting strangers to

fish till the 12th of August; but now the fishings are let, and the high, as

10s.6d. a-day.

The great opening

intersecting the county from Loch Fleet to Laxford, is occupied by one

continued series of lakes and streams—Lochs Shin, Grism, Merkland, More, and

Stack—and a road is in course of formation from Lairg to Laxford, the line

of which is almost perfectly level, and the route will be altogether one of

the finest in Sutherlandshire, as it passes alongst the margin of the

celebrated Reay and Foinnebhein deer-forests, and near the base of some of

the highest mountains, as Ben Hee, Ben Liod, Ben Diraid, Meal Rynies, Saval

More, and Foinnebhein, while various portions along the line are wooded with

dwarfish birch. The lochs and streams are among the best for white fishing

and salmon in Sutherlandshire. Strangers are generally free to fish for

salmon and trout on the Iochs, and for trout in the streams; and in those of

the latter not let, the innkeepers have also the privilege, for a portion of

the year, of permitting persons living at the inns to fish for salmon also.

We are glad to find that this roadway is a couple of feet wider than the

roads round the south boundary, and the west and north coasts, which, for

most part, are only eight feet wide, with an edging of one foot of sward on

each side. The distance to Lax-ford will be shortened to thirty-two miles,

being little more than one-half the present circuit. The road keeps the

north side of Loch Shin and the south side of the other lochs, the forest

stretching along the north.

Having enjoyed the scenery

which the waters of Loch Shin, the neat cottages, the new tasteful church,

and the peaceful manse—all pleasantly situated on a sloping bank of the

lake, with the Free Church and manse on the opposite side of the

river—combine to present to the eye, we proceed along the margin of the loch

for a distance of about two miles, when the road begins to recede from it,

till at last it hides itself from view behind the mountains. Here the

tourist may look upon himself as entering the desert—such it may well be

called; for in the whole tract of country lying between Lairg and Tongue, an

extent of forty miles, and a succession of elevated moorlands lying between

Loch Shin, Loch Naver, Loch Loyal, Loch hope, and the Kyle of Tongue—along

the whole course of which the eye roams over miles of country, in all

directions, of smooth moorland and pasture, either in great plains, or

gentle and extensive inclinations—all is barrenness and waste; and human

habitations are so "few and far between," that only some three or four exist

in all the distance, to cheer the pilgrim with the assurance that he is not

alone in the world.

"Yet e'en this nakedness has

power,

And aids the feeling of the hour"

that feeling so beautifully

described by Byron, where he says

There There is a pleasure in

the pathless woods,

There is a rapture on the lonely shore;

There is society where none intrudes,

By the deep sea, and music in its roar."

4. There is certainly nothing

within the circuit of the British dominions to equal the intensity and

magnitude of the desolation of this vast region ; yet is it but a more

expanded sample of what is to be found in most parts of the county. We speak

of those portions belonging to the Sutherland family, who own at least

four-fifths, or more, of the whole. Every consideration has been rigidly

made to bend to one vast scheme of sheep-farming, and to depopulation as a

supposed necessary concomitant. This was no doubt the most summary, and

seemingly most feasible mode of dealing with the million acres of

Sutherlandshire. The task devolving on the proprietor was, perhaps, too much

for an individual. To conceive of Sutherland-shire, before its vast

fastnesses were made accessible by roads, to realize the consequent

backwardness of the people, and to suppose to one's self the opening up of

lines of communication, ameliorating the social condition of the people, and

to find the means of turning the possession of this great tract of country

to profitable account, is obviously to propose a problem perfectly anomalous

in this country and in this age. The duty was herculean, and we may imagine

the temptation in grappling with it, to adopt the most ready mode that might

be presented to bring it within more manageable compass. This it may have

been which recommended the policy which has directed the course of events in

Sutherlandshire. We would make no invidious reflections. The position of the

noble proprietors and their advisers must have been sufficiently onerous—the

responsibility in itself weighty enough. But the passing traveller cannot

but ponder these things, and ask himself, Can it he so that thus it ought to

be—that sheep should dispossess man, and that while large fertile tracts are

evidently eminently adapted for agricultural purposes? It seems so entire a

reversal of the course of civilization, and would lead to so complete a

reductio ad absurdum; for no doubt, at one time or other, the same reasoning

might have suggested the leaving of the whole of Britain in like manner

waste. We believe Sutherlandshire has proved anything but a profitable

possession. The greater part of the income has, it is understood, for years,

been expended in the course of the great public improvements, roads and

bridges, buildings, &c., which have been carried on. Had not the country

fallen into the hands of so opulent a family as that of Stafford, could such

sacrifices have been made, and public benefits wrought out? In twenty years,

from 1811 to 1831, there were 420 miles of road, and 134 bridges of ten feet

span, and upwards, formed in Sutherlandshire, by the instrumentality of the

Marquis of Stafford, and of Mr. James Loch, his commissioner, seconded by

Mr. Horsburgh, and other local factors, and mainly at the Marquis's expense,

though the other heritors bore their share of greater part, according to

their rentals! Considerable additional length of branch roads has been since

formed. Yet this is but one item. There have been the erection of inns,

harbours, and others, which may be called public works, in addition to all

the details of erection of farm-steadings, plantations, taking in of land,

enclosures, and the public burdens incidental to landed property. Whatever

construction there may be given to the counsels which advised the schemes of

improvement, the greed of pecuniary gain cannot be attributed to the

Sutherland family.

It is but justice to give the

full meed of praise, where there is so much to invite censorious remark. The

roads are most extensive, the inns are really, as a whole, unequalled in the

Highlands, and may well surprise the reasonable Southron. Every thing is

clean, even in the humblest inn, and comparatively comfortable, while in the

best class—and such are to be found from point to point, in all parts of the

county, as Dornoch, Golspie, Helmsdale, Lairg, Aultnaharra, Tongue, Duirness,

Scourie, Loch Inver, Innisindamff, Melvich, and Auchintoul—the conveniences

and style are perfectly surprising. They may well serve as models to the

Highland inns. [These inns, however, cannot be expected to have extensive

accommodation. Two sitting-rooms, and from three to six bed-rooms, is about

the extent of accommodation. A few have shooting-lodges attached, in which,

probably, on a pinch, a bed for a night might be given to a party not able

to rough it otherwise; but in the season there is at times a very

considerable concourse of tourists in Sutherlandshire, and this cannot fail

to increase yearly, and, no doubt, enlarged accommodations will be the

result. meantime, to come early is the best guarantee for room enough—we

would say from the 10th June to the noddle of July, before the great mass of

health and pleasure-seeking Southrons have been able to liberate themselves.

This period also will be found the most likely for a course of steady and

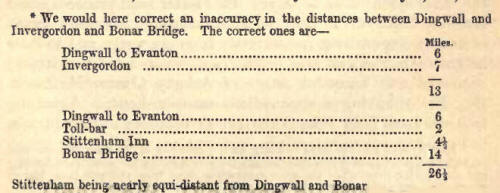

general weather. Here, too, we would correct a mistake we were led into,

page 401. At all the inns there is a conveyance of some sort to be had on

hire, dog-cart or drosky, and even at the smaller inns, as Kyle Skou and

Rhiconich, if nothing better, there will be at least a good spring-cart

forthcoming. We would further remark, that in our notice of the inn of

Stittenbam, between illness and Bonar Bridge, our notice was inadequate. It

was also built by the Marquis of Stafford, when proprietor of Ardross,

though since added to by Mr. Matheson, the present proprietor. It is like

the best Sutherland-shire inns, a really excellent one, and forms a

favourable contrast with, we regret to say, several of the Ross-shire inns.]

The people are universally most civil. They speak better English, and more

generally than in other parts of the Highlands ; and everything bears

testimony to the great and successful efforts for the amelioration of the

population, whatever room there may be for diversity of opinion as to the

line of policy, and however more gravely the means at times adopted may

present themselves in the light of religious responsibility. The people of

Sutherland decidedly rank with the best class of Highland peasantry. They

are universally civil, courteous, and obliging, generally cleanly in their

habits, inured to labour and industry; and the aspect of a country

congregation, in point of neat and respectable attire, is very gratifying.

We also happen to know, that the present noble proprietor not only purposes

subdividing his sheep-farms on the expiry of the current leases, but also

has projected plans of improvement, by bringing land into cultivation, and

generally by the calling into action the energies of a greater number of

experienced tenants, and by the introduction, at the same time, of

agricultural teachers to stimulate and foster intelligent industrial effort.

Much has been done on the larger farms, in keeping progress with the

advancement of agricultural skill and knowledge, and some of the larger

tenants, as we have already indicated, have gone ahead. Still, we believe we

are not mistaken in saying that, generally, pace has hardly been kept on the

Sutherland estates, in drainage and other improvements, with adjoining

counties and estates; but Sutherlandshire is so unique, so gigantic a

possession, that circumspection is required in drawing comparisons. The

demands on the Duke are necessarily so excessive, that few other men in his

situation but himself could contrive to face them at all. For instance, in

the first year of the recent potato failure, he actually expended £27,000 in

the providing means of subsistence, by employment and provision of food, for

the starving population of Assynt, Edderachillis, and Duirness alone.

Credit is now unreservedly

given to the good intentions by which the late Duchess-Countess and her

noble husband were actuated, and the liberal spirit of the present Duke, in

dealing with these his northern possessions in all the specialties of their

position, is universally acknowledged. Let us hope that what has been done

may prove to have been like the cutting down to the roots of a plant or

tree, overgrown and unproductive, despoiling it for a season of its leafy

honours, but only that, after a time, it may spring up anew, luxuriant with

blossom and fruit, Let us believe that in the hand of providence the

excision was permitted, and brought about for good and wise purposes.

But enough of such digression

which we have been led into, because this vast compass of country, so

peculiar in its aspects as Sutherlandshire is, cannot fail to excite the

tourist's speculation as he wends along, and subject the noble owners to

critical comment.

5. The unparalleled moorland

expanse of country intermediate between Lairg and Tongue, treeless and all

but houseless, presents many stretches of delightful verdure, and generally

in Sutherlandshire, except in the deer forests, the heath is kept very

short, being burnt every seven years, so that the livery of the country is

generally pleasing.

Advancing northwards from

Loch Shin, the conical height of the mighty Ben Clibrick, on the south-east

side of Loch Naver, right a-head, fills the eye. To the west and northward

the expanded circuit is occupied by Ben More of Assynt, Ben Liod, Ben Hee

(one of the highest mountains in Sutherlandshire) Ben Hope, and Ben Loyal,

while behind us the Ross-shire hills make a continuous mountain outline. A

striking peculiarity distinguishes the mountain scenery of Sutherlandshire.

The great mass of the country is considerably raised, forming in most

quarters an elevated table land of smooth moorland or rocky eminences. On

this universal base, diversified by river courses and straths, and

inequalities of all sorts, are piled a great array of generally detached

mountains—huge superstructures towering, each in isolated grandeur, from

3000 to 3500 feet above the level of the sea. In consequence there is less

of continuous mountainous screen than in most other parts, while each

giant-like mass stands out in its own full proportions, always, too, in some

of its corries and sides, sheer and abrupt from base to summit, most

variously modelled, and shaping itself differently, according to the point

of view; when the outlines of different mountains comingle, assuming

strongly-defined appearances; and the terminal aspects of the different

masses repeatedly presenting themselves in cones, peaks, and pyramids,

comprising the full elevation of the hulk, and thus of a magnitude seldom

met with elsewhere, and nowhere in the Highlands in such array.

What may be called glen and

valley scenery is of rare occurrence. The river and stream courses are open,

their channels generally shallow, and it is among the lakes and inlets of

the sea, the jutting headlands, and the upper recesses of the mountains, and

in panoramic amplitude and pervading solitude and silence, that we are to

look for the characteristic features of the country.

As we advance to Aultnaharra,

Ben Clibrick rules sole monarch of the waste to the eastward, in which

direction the country is destitute of marked elevations, excepting one hill

on the east side of Loch Loyal; but in the distance, the two well-known

pyramidal hills, called the Paps of Caithness, are descried. Ben Clibrick,

as marked upon the map, is situated as exactly in the centre of the county

as if a pair of compasses had been applied with geometrical precision in

fixing its position; and from its great height, upwards of 3000 feet, and

centrical situation, the view from its summit is as extensive as it is grand

and various, embracing the German Ocean, the great North Sea, portions of

many of the surrounding counties, and even, with the advantage of a clear

day, the Orkney Islands.

After a ride of twenty-one

miles over the dreary Crask (a pass), we reach the solitary inn of

Aultnaharra, or Aultnaherve, near the head of Loch Naver, now as admirable

as it is remote. At a little half-way house a feed of corn, or meal and

water, can be had.

6. At Aultnaharra, a branch

from the Tongue road diverges on either hand, one on the left leading to

Loch Erriboll, the other, through Strathnaver, to Farr. Of the former, the

ascent for the first four miles is constant and considerable; but on pausing

and looking behind, the extensive rich green Lonn (meadow strath) of Moudale,

the commanding and grand view of Ben Clibrick, and a peep of Strathnaver,

prove quite refreshing. Soon the prospect opens on the other hand, and a

great stretch of wild scenery is presented to view. About nine miles from

Aultnaharra we enter Strathmore. Above this strath, which forms a

continuation of the line of Loch Hope (a fresh-water lake running parallel

with Loch Erriboll), there is enjoyed an interesting and varied view of the

rugged Ben Hope, at the south end of the east side of the loch. This

mountain, which on this side exhibits a perpendicular precipice almost along

its whole height, is said to be distinguished by the property of emitting,

previous to tempestuous weather, a hollow sound indicative of the

approaching storm, such as sung by the Mantuan bard

"Altis

Montibus audiri fragor."

[The same phenomenon is said to be characteristic of the Cairngorm mountains

in Inverness-shire.]

7. Aultnacaillich, in

Strathmore, is the birthplace of Rob Donn, the Gaelic poet. Robert Calder

Mackay, or, as he is generally called, Bob Donn, is regarded as the Burns of

the North, as Duncan Ban Jfaclntyre is of the South Highlands; and, indeed,

their poems form the only two miscellaneous collections of note of Gaelic

poetry. The former was born at Aultnacaillich in Strathmore, in 1714; the

latter in 1724, at Drumlairhaig in Glen Ogle, Perthshire. Both were

uneducated men, but their productions bear the stamp of vigorous genius. An

able memoir of the former, by one of the first Gaelic scholars of the age,

has been published, along with his songs and poems. He would seem to have

been a man of no common grasp of intellect; a shrewd observer, possessing

powers of caustic satire, which, however, he employed always, and that with

great independence of spirit, on the side of truth and morality. his

compositions are all extemporary, struck off on the spur of the occasion;

and his facility in building the lofty rhyme was not a little remarkable.

There is much playful vivacity and keen sense of the ludicrous in his

humorous pieces; and, in the more serious efforts of his muse, he displays

justness of thought, propriety of sentiment, tenderness and warmth of

feeling, and correctness of taste. His social powers made him a great

favourite with all classes; but though he would appear latterly to have in

some degree given way under the baneful influence of frequent convivial

excitement, his character generally was unmarked by the aberrations which

too frequently stain the career of genius ; and, indeed, his moral

deportment was such, that he was nominated an elder of his native parish at

a time when the qualifications for that office were rigorously investigated.

His life was successively spent as a drover, gamekeeper, superior cowherd or

bowman, and as a small farmer; and, for a time, he joined the first regiment

of Sutherland Highlanders, but more in the capacity of a privileged

favourite, than of a private soldier. Rob Donn's biographer ranks his

compositions as inferior, in point of rhythmical beauty, to those of some

other bards, especially of Duncan NlacIntyre ; but he accounts for this from

the peculiarities of the dialect in -which he wrote.

"The highest efforts of our

bard's rhythmical powers is undoubtedly to be found in `Piobaireachd

Iseabail NicAoidh,' a song composed in praise of a young lady, to the

well-known air of the pipe tune, `The Prince's Salute.' To those who have

attended to the variations of that air, as played properly upon the great

Highland bagpipe, it cannot appear but as a very respectable effort, that

the bard has met all its variations, quick and slow, with words and with

sentiments admirably suited both to the air and to his subject. Duncan

1facIntyre's 'Beinn D'oblorain,' is an effort of the same kind, which we

grant is superior, indeed almost marvellous. But of the two, and we believe

of some others of the same kind, we may claim priority for Rob Donn."—" If

Rob Donn's poetry be sometimes found deficient in harmony, and its

phraseology be sometimes pronounced by Gaelic critics in a measure uncouth,

it will not be generally denied that he possesses the redeeming qualities,

under these disadvantages, of nerve, and strength of mind and sentiment, a

manly vigour of intellect, a soundness and perspicuity of good sense, that

place him as a bard beside the most popular names of his country's

minstrels. In the properties of true poetic fertility, of wit and humour

when he is playful, elevation of sentiment when he is solemn, soundness of

principle and moral feeling when he is serious, if we dare not say that he

stands the first of Gaelic bards, we may say with his contemporary, Mr. John

Mackay of Strathmelness-

Leis gach breithcamh d'an

eoldan,

Bidh cuimhne gu brath air Rob Donn.'

'With every judge of poet's

fame,

Rob Donn's will live a deathless name."'

We subjoin the following

sensible observations from the same author, on the elegiac poetry of the

Highlands. "This solemn compositions may be said to present the bard's

character in its strength. By these, we mean principally his elegies. It is

generally known, that over the Highlands of Scotland, until days yet not

long gone by, every district had its bard or bards of higher or lower name ;

and when any individual of provincial or public celebrity died, it was

customary for their death to be followed by an elegy, or some poetic praises

to perpetuate the remembrance of their virtues. That such praises should

always be justly bestowed, and not partake, even when merited, of poetic

exaggeration, could not be expected. Feelings of personal regard, of

partiality to the dead, and hopes of benefit from the living, would

frequently, no doubt, enlist poetic talent to say the best that could well

be said. We have good authority for maintaining it as beyond controversy,

that our author on such occasions never once was hired; never was enlisted

by any prospect of interest or advantage, to eulogise where he could not

conscientiously commend. And his commendations bestowed in elegy will

evince, we conceive, even to readers entirely strangers to the history of

the individuals to whose memory they are devoted, an honesty of intention, a

sincerity of mind, a purity of sentiment, that cannot fail to place the

author himself in a conspicuous view, as an upholder of truth, while he

describes the virtues of those whose fame he commemorates. Even the admirers

of Gaelic song will allow that, in elegy especially, our Highland bards

introduced almost universally much of what we cannot more correctly

denominate than rant and bathos. Imams eery excellencies and virtues,

factitious distinctions and pretensions, are dwelt upon with all the

solemnity which the elegiac muse ought to devote alone to solid and

substantial virtues. We have no desire to detract from the reputation of his

brethren, by upholding the character of our author; many of his brethren's

compositions of this kind are excellent, and several of them, abstractedly

considered as poetical effusions, we would rank fully as high as Rob Donn's;

but we cannot but feel hurt at the bombast, and sentences absolutely without

meaning, with which they too frequently abound, and by which they lower, in

the reader's esteem, the character they designed to commend, and give an air

of littleness to their author's character of mind. All this may seem to

those unacquainted with Gaelic song to be somewhat like falling into the

error we would reprove; commending what merits not either censure or praise,

from its very insignificance. What can be the pretensions to excellence of

the 'unlettered muse' of the highlander? It is from an impartial conviction,

we trust, of her numerous and striking excellencies, that we regret the

blemishes which have attached to her achievements. We are well aware, and

can never cease to lament it, that the entrance of the native muse of

Scotland upon the literary stage was singularly unfortunate ; that it

excited prejudices in the public mind which ages may not remove. The Gael

and their friends have stormed and raved about their darling Ossian. The

Saxons have knit their brows, and vented their spleen at pretensions too

arrogantly made, and assuredly not supported by any paramount testimony.

Were we called upon to write an epitaph for the Ossianic controversy, it

would be a short one: `Est in medio veritas.' We wish it had never been

raised. The eliciting of truth, not to speak of the stubborn maintaining of

error, besides the establishment of the one, or the just downfall of the

other, by legitimate argumentation, can seldom be achieved without certain

other effects following the excitement of party feeling, that may prove much

more injurious in the end, than if the actual subject-matter of controversy

had been left to sleep its own sleep. And it does by no means astonish us

that, from the character of the controversy regarding the authenticity of

Ossian, multitudes of our Saxon friends should both experience and testify a

prejudice against all claims to excellence put forth for the native poetry

of our northern land. But while we wonder not at it, we cannot but lament

its existence.

"But to return to our author:

we conceive that we arrogate for him no undue place, in saying that in

elegiac poetry he is, upon the whole, peerless among his fellows. From the

local circumstances of other districts, and of clans in the generations gone

by, there is not only in their other poetry, but also in their elegies, a

martial strain observable ; a spirit bordering on chivalry pervades them.

But our author lived in a region of peacefulness ; he was not brought up in

the habit, or scarcely in the remembrance, of feud, and field, and battle

fray. His elegies, consequently, will be found of a different complexion

from those of most other bards." Rob Donn is buried in the church-yard of

Duirness.

8. At Aultnacaillich there is

a fine waterfall on the right, and on the left the well-known round burgh or

tower of Dornadilla, about twenty feet of a segment of which in height still

remains. It is just about the size of the Glenelg Towers, being twenty-seven

feet inside diameter, and fifty yards external circumference. Cordiner, who

gives a view of this burgh, showing it to have been pretty entire in his

day, supposes it to have been erected by a Scottish prince, DornadilIa. At

Cashel Dhu (the Black Ford) thirteen miles from Aultnaharra, and five from

Erriboll, where the winding river is crossed by a little flat-bottomed boat

or Coble, and where many have been drowned for want of such a shallop, is a

small inn; commanding, in front of it, a view of the mountain Ben Hope,

nowhere in Scotland surpassed for grandeur and sublimity. From Erriboll, the

pedestrian traveller bound for the westward may either proceed round Loch

Erriboll, or go on to Huelim ferry (three miles and a half distant) by a

road which is six or seven miles shorter.

9. The distance from

Aultnaharra, through Strathnaver to the inn of Bettyhill of Farr, is about

twenty-four miles. This road has not been completed, being carried only for

nine miles down the strath, beyond which there is as yet merely a "bridle

road." Loch Naver is about eight miles long, and is succeeded by a river,

one of the best in the north for salmon, bordered by extensive tracts of

luxuriant meadow, and improvable land, lined, as is the loch side, except by

the base of Ben Clibrick, with the most softly inclined slopes, garnished

with occasional copsewood of dwarf birch. Of old there were towers in sight

of each other all along the strath. Latterly, in every township one or more

comfortable tacksmen's houses were to be seen in close succession, and

upwards of 1200 people resided in this strath. Now, for twenty miles, not a

house is to be seen except shepherds' dwellings at measured distances. One

cannot but regret the absence of living beings in such a scene, and of the

want of those little hamlets usually seen in most Highland glens, and by the

sides of clear mountain rivulets. Where are these? Wormwood, and a little

raised turf, alone mark the places where they stood; the down of the thistle

comes blowing from the sod over the roof-tree, the fires are quenched, and

the owners are far from the land of their fathers.

10. A few miles beyond the

inn of Aultnaharra on the north side of the road, commences the boundary of

the Reay country, now the property of the Duke of Sutherland. Ben Loyal's

lofty summit here begins to rear itself conspicuously, presenting to the

fancy at one point of view the form of a lion couchant, and at another a

close resemblance to the royal arms, "the lion and the unicorn fighting for

the crown." Beneath, on the east, lie the still waters of Loch Loyal, with

its verdant islands, on the margin of which the road winds around the foot

of the mountain, forming, along its whole extent (of about six miles), a

truly beautiful and picturesque ride; but as the road keeps the west side

immediately along the base of Ben Loyal, its fantastic outline is almost

lost. On the banks of Loch Loyal, previous to the sheep-farming depopulation

system, dwelt some of the most comfortable tenants in the county of

Sutherland.

This loch is succeeded by two

others, Craggy and Slam, all abounding in trout, char, salmon, and large

pike.

At a short distance from Loch

Loyal, the Kyle of Tongue, a long arm of the sea, with its low rabbit

islands and the large rocky isle of Rona at its mouth, greets the sight, and

in a few minutes the woods and plantations around the old baronial residence

of Tongue present themselves in full view. Tongue house is beautifully

situated at the foot of a lofty craggy mountain, on the neck of a long point

or tongue of land projecting into, and about the middle of, the east side of

the Kyle, the waves of which wash the very walls of the garden; whilst the

"tall ancestral trees" that surround it form at once an ornament and a

shelter, and pretty extensive plantations are flourishing around, a

peculiarity to be noticed where trees are few and far between. The mansion

itself is an old structure, no ways distinguished in its architecture, but

interesting as a specimen of the honest simplicity of taste of our

forefathers, and although every comfort is to be found within its exterior,

the work of successive generations. This fine domain, the ancient seat of

Lord Reay, chief `of the clan Mackay, has now become the property of the

Duke of Sutherland; and although it is natural to feel regret in the

necessity which has denuded the former owner of the hie of his forefathers,

still it is matter of rejoicing to all the numerous tenantry of the estate,

that his successor is their next neighbour, the Duke of Sutherland, than

whom they could scarcely wish a more liberal landlord.

On an eminence near the sea,

projecting from the .foot of Ben Loyal stands Caistil Varrich, the ruins of

an old watchtower. The scenery about Tongue is altogether very grand, an

extensive semicircle of mountains stretching around ; in the centre Ben

Loyal, 2508 feet in height, spreading widely at its base, and cleft above

into four splintered summits, each strongly defined, and receding a little,

one behind the other, and the southern extremity of the western limb of the

mountain ranges, otherwise somewhat mountainous, though of no considerable

elevation, suddenly shooting up in the huge mass of Ben Hope to a height of

3061 feet. On the opposite side of the Kyle, the receding slopes are

partially occupied with cultivated fields.

So much is the surface of

Sutherlandshire interspersed with sheets of water, that from one eminence in

the parish of Tongue, no less than 100 lochs are visible at once—a

peculiarity still more strikingly exemplified in the western section of the

county.

The village of Kirkiboll,

which is pleasantly situated upon the slope of a hill, is within rather more

than a mile of Tongue House, and contains only, besides the manse and a

commodious inn, a few scattered cottages. Kirkibol] is about four miles

north of Loch Loyal, and eighteen from Aultnaharra.

11. Until recently there was

no regularly made road westward from Tongue towards Erriboll. The traveller

required a guide to pilot his dubious way across the rugged mountains, and

over the trackless waste of the Moin, a highly elevated boggy moorland,

stretching from the base of Ben Hope and Ben Loyal to the sea, and between

Loch Hope and the Kyle of Tongue, a width of eight miles; but now, thanks to

the late noble duke, (by whom, on his acquisition of the Reay country in

1829, eighty miles of road were formed at his own expense,) there is an

excellent road in this direction, by which the traveller may proceed,

without fear of broken bones, or the perils of bogs and pitfalls, as

formerly, along the whole west coast to Assynt. Crossing, therefore, the

Tongue Ferry, about a mile wide, the passage of the :Min, which formerly was

the laborious achievement of an entire day, may now be accomplished in an

hour's time with ease and comfort. The expense attending the construction of

this piece of road must have been very great, from the mossy nature of the

ground: the foundation was formed with bundles of coppice wood, laid in

courses across one another, a layer of turf was next placed over these, and

the whole being covered with gravel forms a road of the best description.

Great ditches and numerous smaller drains are excavated in different parts

on either side to contain the moss water.

12. The north coast of

Sutherland is deeply indented by three arms of the sea, the Kyle of Tongue,

Loch Erriboll, and the Kyle of Duirness, or Grudie, occasioning as many

ferries to be crossed between Tongue and Cape Wrath. The river Hope to the

west, and the Naver and Hallowdale to the east, of Tongue, are likewise as

yet unsupplied with bridges. But these rivers are crossed by a large flat

boat, which is moved from one side of the river to the other by means of a

windlass and chain, attached underneath to the boat, and connected also with

the banks. These boats admit a carriage, without the horses being

unharnessed, and the largest is capable of conveying nearly two hundred

passengers, and of carrying seven or eight tons' weight at a time. About the

best views of Ben Loyal and Ben Hope are obtained in crossing the Moin, the

castellated summit of the former coming laterally under the eye, while the

great shelving precipice in which the rounded highest mass of Ben Hope

terminates on the northwest, and to which the mountain rises in long

successive stages, is displayed in its whole extent. More to the west,

Foinnebhein and Benspionnadh, south of the head of Loch Duirness, uproar

their extensive and varied heads and precipitous corries above the lower

ranges which immediately encircle Loch Erriboll.

13. From the banks of the

river Hope, which is crossed at its outlet from the lake, and in the descent

to it, and again ascending the eminence forming the west bank of the river

Hope, one of Nature's grandest scenes, lies displayed before us. The huge

Ben hope, which raises its shaggy head about 3000 feet above the level of

the sea, stands full in view at the eastern head of the lake ; in the

intermediate space lies the wide unruffled expanse of lone Loch Hope,

embossed amid long ascending slopes, and brightened perhaps by the "yellow

radiance" of the setting stn to the appearance of one unbroken sheet of

burnished gold.

"Nor fen nor sedge

Palute the pure lake's crystal edge.

Abrupt and shear, the mountains sink

At once upon the level brink;

And just a trace of silver sand

Marks where the water meets the land;

For in the mirror, bright and blue,

Each hill's huge outline you may view.

There's nothing left to

fancy's guess,

You see that all is loveliness;

And silence adds, though these steep hills

Send to the lake a thousand rills,

In summer tide so soft they weep,

The sound but lulls the ear to sleep;

Your horse's hoof-tread sounds too rude,

So stilly is the solitude."

Leaving this scene, at a

distance of about two miles, we reach the small rather out of the way inn of

Heulim, on the banks of Loch Erriboll, in descending to which, and again

ascending to Erriboll, the view is exceedingly fine.

Immediately below, encircled

by mountains, lies the beautiful bay of Camusinduin, a sheltered indentation

of Loch Erriboll (itself an arm of the North Sea, running about ten or

twelve miles up the country), further protected by a rocky eminence

connected with the shore by a gravelly peninsula, and celebrated among

mariners as one of the finest and safest harbours in the kingdom, deserving,

as much as its rival of Cromarty on the opposite coast, the appellation with

which the ancients honoured the latter of "Portus Salute." Seldom, during

the prevalence of a northerly wind, does this haven want the embellishment

of numerous vessels riding safely at anchor, and with their different yawls

gliding swiftly along in every direction, and many parties of sailors

enjoying their rough sports on the beach, giving animation to a scene

otherwise as sequestered as may be.

From Heulim, the road towards

Rispond passes Erriboll, three miles and a half distant, and then proceeds

along the shore of Loch Erriboll. On approaching the head of this inlet of

the sea, the scenery becomes wild and imposing. Here stands the stupendous

rock of Craignefielin, whose frowning front overhangs the road. A little

farther on, the battlement-looking heights of the rocks of Strathbeg come

into view in a southerly direction; whilst to the S. W. and W. are the hills

of Foinnebhein, Cranstackie, Benspionnadh; and to N.W. and N. the range of

hills called Beauntichinbeg, which terminates above Rispond, in the hill of

Benaheainnabein, forming altogether a mighty mountainous amphitheatre. This

road affords many beautiful views, both of the loch and of the surrounding

scenery; and brings us, at a distance of fifteen or sixteen miles from

Ifeulim, to Rispond, at the western corner of the opening of Loch Erriboll,

an extraordinary-looking place, worth turning aside for a few minutes to

inspect. It is situated on a small creek, on all sides encompassed by one

continued series of naked rocks, and is altogether an out-of-the-world sort

of spot. Rispond is, however, well adapted for a fishing-station, being

situated at the mouth of Loch Erriboll; and of its advantages in this

respect, the intelligent gentleman who resides there for a time successfully

availed himself. Now, unfortunately, it has been discontinued, and as there

is no curing establishment on this part of the north coast, and as that at

Loch Inver has also been abandoned, it is no object for vessels to come the

way, and there being no demand, the energies of the fishing population are

paralysed, and the treasures of the deep are to them comparatively as if

they were not. The view from the summit of the highest rock, towards the

sea, is very fine : in the distance the eye roams, without finding a

resting-place, over the mighty waters of the great Northern Ocean, which, as

they recede from the sight, seem to mingle with the horizon. Nearer at hand,

several small islands, one of which (Island Hoan) is inhabited, with the

numerous vessels that here spread their white wings to the swelling breeze,

give variety to the prospect ; whilst the high perpendicular cliff of Whiten

Head, to the east, forms a prominent object among the many wonders of this

"iron-bound coast."

Instead of making the circuit

of the loch, the pedestrian tourist may cross at the ferry at Ardneachdie to

Port Chamil. It is nearly two miles in width ; but the boat and crew are

good. The road to Rispond (half a mile) turns off to the right three miles

and a half from the ferry, at Calleagag bridge.

14. Two and a half miles

beyond Rispond, and one mile from the inn of Durin, is situated the creek

and Cave of Smoo, or the Uaigh Mhore, a very remarkable natural excavation,

of gigantic dimensions, formed in the face of the solid rock, which is

composed of limestone. Its entrance and interior are of nearly uniform

width, thus affording the broad light of day to its farthest extremity,

which is aided by a circular opening at the top, after the fashion of a

cupola, and called by the Gael "Nafalish," or the sun. It lies at the inner

extremity of a long narrow inlet of the sea and a little way up the course

of a burn, which, instead of falling over the face of the cliff, finds its

way through another vertical opening, forming a remarkably fine waterfall,

into an inner spacious compartment, which communicates with the outer cave.

This last is perfectly dry. Behind the eastern side of the entrance is a

massive spreading pillar, that supports the ponderous projection, and forms

a small arch of five or six yards wide between itself and the interior wall.

The vaulted roof of the cavern reverberates, with loud and repeated echo,

the minutest sounds, and gives to the voice a fulness of intonation that

increases its power many fold. Viewed from the inner extremity, the spacious

archway, of a span wide for its height, and of the great vaulted roof, is

exceedingly imposing. The height of the entrance is fifty-three feet, above

which there is a space of twenty-seven feet of precipitous rock, making the

total height of the rock in the centre eighty feet, but it rises higher as

it advances. The depth of the cavern is 200 feet, and its width 110 feet.

The roof projects about fifty feet beyond the pillar, and of this portion

the centre has given way. On the west side is an opening of about twenty

feet in height and eight feet in breadth, that leads to an interior cavern.

The access to it is over a low ledge of rock which blocks up the lower part

of the entrance, and before which there is a deep pool, formed by the water

oozing from underneath the ledge. A partial and obscure view of the interior

can be obtained by clambering up the rock, as the roof of this chamber is

also perforated. But though the ledge can be reached with a little

scrambling, the visitor ought not to content himself without a closer

inspection, though the assistants make rather an unconscionable demand for

their services, for which they ask fifteen shillings but take less—a rate of

charge which the intelligent postmaster, who lives hard by, should see to

have rectified. The further examination is achieved by having a boat placed

in the outer pool, from which to step on the barrier. It is then lifted

across with some little trouble—as the only boats at hand, and there are

several generally on the beach of the little inlet, are larger than need be

for the purpose of this exploration—and launched on the inner pool, which

entirely fills this chamber. The boatmen supply candles to make the darkness

risible. Embarked on this subterranean lake, we find ourselves beneath a

vaulted roof, which rises high overhead. The opening mentioned from above is

in the roof of a branch at the further end of the excavation, and gives

admission to a cataract of water, formed by the burn alluded to, which comes

foaming down from a height of rather more than eighty feet, on the face of

the limestone rock. This is really a fine waterfall, apart from the peculiar

circumstances of its position, and forms one of the most remarkable features

of the whole. From midway of the wall of the gap through which it pours,

another opening slants up to the surface, giving a further supply of light,

and affording means of viewing from above the central portion of the

cascade, which, by the way, is not discernible from the entrance to this

second cavern. The length of this interior apartment is seventy feet, its

breadth thirty `here narrowest, the pool seemingly of considerable depth.

There is yet a third cavern

extending farther into the bowels of the earth, to which an entrance on the

west side of the cataract we have just mentioned conducts. This entrance is

formed by an opening nine or ten feet high, but bridged over by an arch of

stone, which contracts the opening under which the boat has to be pushed, to

a height barely sufficient to admit the passage of a small-sized boat. To

effect this transit, it is necessary for the party in the boat to dispose

themselves, as best they can, in a recumbent posture, else they run the risk

of acquiring bumps upon their craniums not recognised in the nomenclature of

phrenology. This inner apartment is a region of utter darkness: with the aid

of candles or torches, however, we discover ourselves in a narrow cavern,

which is for one-third of its length occupied with water. This cave

gradually decreases from a height of forty to twelve feet, is about eight

feet in breadth, and extends in length about 120 feet. Not far from the

extremity of the cave is a deep pool, which stretches under the rock, and no

doubt communicates underneath with the waters of the second cavern. Here

terminates the exploratory adventure, and the visitors must retrace their

way as they entered. In doing so, the outlook through the orifices to the

increasing brightness is picturesque.

Having again emerged into the

light of day, and ascending the rock, we discover the brook which forms the

cascade in the second cavern; it dashes headlong down a rocky chasm, meeting

as it descends several projecting shelves, which form minor falls ere it

precipitates itself finally, with "the voice of many waters," into the

gulf beneath. When this brook is flooded after heavy rains, the water nearly

fills the aperture of the chasm, and if there happen to be a strong

northerly wind, the spray is driven upwards, forming a fine natural jet

d'eau.

The cave is immediately below

the public road, the burn making its descent on the left hand, while the

pathway down branches off on the right.

Reviewing the effect which

the appearance of this magnificent cavern has upon the mind, we cease to

wonder that the strange tales that hang by it find implicit believers among

so many of the country people. Its solitude, its dark recesses, and deep

gulfs, are well calculated to aid the suggestions of superstition, for which

there is naturally an aptitude, if not a good foundation, in the mind of

man: this cavern has been accordingly peopled with spirits embodied in all

the forms, and endowed with all the attributes, that distinguish the

multifarious genii of Highland mythology, the "dainty spirits" that knew "to

swim, to dive into the earth, to ride on the curled clouds." But those

spirits are now departed spirits: they have evanished before the meridian of

our intellectual day, and have scarce left a "local habitation or a name" by

which to be known, should they again revisit "the glimpses of the moon."

15. Leaving Smoo, the road

lies through what, compared with the ground over which we have already

passed, may be called a corn country, being more open and level, and having

numerous fine fields; the district between the opening of Loch Erriboll and

the lower portion of the Kyle of Duirness being a table-land of fine

limestone.

Seven miles from the ferry of

Heulim, we reach the excellent inn of Durin. Farout Head, the most northerly

promontory on this part of the coast, stretches out for about three miles,

forming a fine bay on either side. On the shores of the western bight—the

bay of Duirness—stands the old house of Balnakiel, the chosen summer

residence, in times of yore, of the Bishops of Sutherland and Caithness, and

latterly of the Lords of Reay; and the small parish church of Duirness, an

old structure, formerly a cell of the Augustine monastery at Dornoch, which

was an offset of that at Beauly. The interior of this edifice is at present

in a state of untidiness, quite discreditable for a place of worship to be.

On the further side of a broad peninsula, which landlocks the upper part of

the Kyle, Kooldale farmhouse is pleasantly situated. All around Balnakiel

and Keoldale are fine arable fields and the richest pasture land, and the

promontory of Farout Head is, to a large extent, covered with luxuriant

pasture to the summit of the lofty cliffs at the point. These, with

Balnakiel, and the church and churchyard, are worthy of a four miles' walk

from the inn. From the highest point of the headland, the lighthouse and

terminal outlines of Cape Wrath meet the eye; in one direction Whitten Head,

the lofty and precipitous termination of the east side of Loch Erriboll,

forming a prominent object in the long line of coast in sight, as far as

Strathy point to the east; while the hill of Fashbein, near the cape, with

Foinnebhein and Ben Spionnadhlofty mountains south-west of the Kyle—with Ben

Hope and Ben Loyal in the distance, to the south-east, form a fine mountain

screen on one hand—the boundless ocean expanding all to the north of the

coast on the other, with the Orkneys looming in the north-eastern horizon.

The cliffs of Farout Head attain an elevation of 300 to 400 feet. In the

churchyard of Duirness lie the remains of that highly gifted son of song,

already spoken of, Robert Calder, better known as Robert Donn, or Mackay,

which latter surname, however, some maintain to be erroneous: a monument of

neat design, and with appropriate inscriptions in Gaelic, English, Latin,

and Greek, has lately been erected here to his memory by the admirers of his

genius. This cemetery also contains some quaint inscriptions: One on a

sculptured tombstone within the church, over the remains of a person

distinguished in the local history of the district, as a noted freebooter,

and by the appellative of Donald Mac-Mhorchie-icevin-mhoir, abbreviated

Donald Mac-Corachie, and said to have been inscribed by himself, runs thus

:-

"DONALD MACK, heir lyis lo;

vas ill to his frend and gar to his fo, true to his maister

in veird and vo. 1623."

In August 1847, a vessel was

wrecked on a Sunday morning on the high isolated rocks on the east side of

Farout Head, when all hands perished.

About three quarters of a

mile west of the church, near the sea, is the cave, as it is called, of

Poul-a-ghloup, which is, properly speaking, only an immense gap or cavity in

the earth, of great depth, and communicating by a long, subterraneous

passage with the sea, whose waves, as they roll, first into a long narrow

seaward fissure in the limestone cliffs, which are here much and sharply

indented, and then along the passage to its inmost extremity, resound with a

terror-striking growl.

16. Cape Wrath—the Parph of

ancient geography—distant eleven miles from Duirness Ferry, which is two and

a-half miles from the inn, is a remarkably bold headland, forming the marked

and angular north-west extremity of Great Britain; it is, consequently, one

of the extreme points of our island, and on that account—like John-o'-Groat's

or the Land's End—strangers desire to visit it. Cape Wrath, with its

stupendous granitic front, its extensive and splendid ocean scenery, and the

peculiarly wild character of the country by which it is approached, is

invested with an interest which few promontories on the British coast can

equal.

The greater part of the shore

is here so very precipitous and steep, and many of the cliffs so

overhanging, that it cannot with safety be viewed to advantage from the

land, without great trouble and difficulty; so that, with favourable

weather, the survey of this magnificent headland is generally attempted by

sea; but the strong currents and high-swollen waves that at all times roll

at the Cape, joined to the risk of one of those sudden storms or squalls

that characterize this coast, frequently deter persons unaccustomed to

boating from making the attempt. There is no boat to be had nearer than

Duirness, and the demand for one is 30s. The outermost point of the rock

consists of a granitic gneiss, waved in structure, and greatly contorted by

the intrusion of granite veins.

Proceeding by land, we cross

the Duirness Ferry. This road, from one of the ascents of which the views of

Foinnebhein and Spionnadh are particularly fine, does not keep by the coast,

but winds through a high moorland country, the lofty mountain of Fashbein

being on the left hand, and Skrisbein on the right, for about four or five

miles, when a valley leading down to Kerwick affords a view of the sea and

of the very singular pinnacle of Stacko-Chlo. This is a high pillar, rising

probably to the height of 200 feet out of the sea, but so far below the

height of the neighbouring cliffs, as to he remarkable only from its

detached position, and the regularity of the old red sandstone strata of

which it is composed. From this valley the road takes several wide curves,

and, when within two miles of the lighthouse, branches off to a small boat

harbour in the deep and rocky bay of Clash Carnoch; then, winding up a steep

hill, we suddenly, but not until within a few hundred yards of the

buildings, come in sight of the lighthouse, which, with its regular outer

walls and turreted buildings, resembles a small fortification. On a near

approach, the perfect order and cleanliness that pervade the whole

establishment are experienced as quite delightful and refreshing; the stones

used are all of the durable and beautiful granite, dug with much trouble out

of Clash Carnoch; but so difficult of access and remote was the situation,

that the expense of procuring the other materials was very great, and it is

understood that the whole original expense was nearly £14,000 sterling. The

view obtained from the top of the tower more than repays the trouble of the

journey from Duirness. To the south-west, the distant Butt of Lewis is seen

in clear weather, while the wide expanse of ocean that rolls in the same

direction against the rocky shores at the mouth of Loch Inchard, or on the

sandy bay of Sandwood, is, from this elevation, accompanied with an idea of

magnitude and vastness unknown at other points of the coast. To the east,

again, the tall Hoyhead of Orkney, and, in fine weather, even the island of

North Rona, at a distance of fifty miles, is distinctly visible, and also a

long range of bluff, iron-bound coast, on the mainland, as far as Strathy

Head. Several small rocky islands start up at different points, of which

Balque,

"An island salt and bare,

The haunt of seals and auks, and sea-views' clang,"

is the largest. It lies at

some distance from the shore, and appears a lumpish mass on the breast of

Ocean. Nearer the shore is the pinnacle of Buachil (or the Herd), of

considerable altitude, and which, having a wide base and sharp point, might

at this distance be mistaken for a large ship under full sail. Immediately

out from the cape are several sunken rocks, over which the sea foams and

rages in the mildest weather with appalling fury. A reef of perforated

rocks, which juts out into the sea, is very striking. The highest precipice

is not less than 600 feet, and, in one place, a steep declivity of red

granite, remarkably imposing, terminates in a precipice of great height. But

the wonders and magnificent front of the cliffs in this quarter can only be

seen in their true character from the sea. From that direction, abrupt and

threatening precipices, vast and huge fissures, caverns, and subterranean

openings, alternately appear in the utmost confusion, while the

deep-sounding rush of the mighty waters, agitated by the tides among their

resounding openings, the screams and never-ceasing flight of innumerable

sea-fowl, and often the spoutings of a stray whale in his unwieldy gambols

in the ocean, form altogether a scene which none who has witnessed it can

ever forget. |