|

Of the Russian, - who can say?

When the night is gathering, all is grey.

Kipling The

ballad of the king’s jest

I cannot forecast to you the action of

Russia.

It is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.

Winston Churchill

3rd October 1939

Never under-estimate the Russian.

Menachem Ben Yami

(former soldier

in

the Red Army Jewish Brigade)

The vast and populous

land of Russia, and its past empire, or the later Soviet Union, have

always carried a mystique and an attraction to most western observers.

From the wild snowy wastes of Siberia to the arid deserts of central

Asia, and from the Baltic and Arctic ports to Vladivostok on the

Pacific, and Sebastopol on the Black sea, the region and its peoples

have been too extensive to regard as a single entity. Ancient tales and

records of fur-clad Tsars and Tsarinas, of strange hypnotic characters

like Rasputin, the ‘mad monk’, of Emperors like Peter the Great, of the

medieval cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg were raw material for

fairly tales and legends. The Greek Orthodox faith with its bearded

priests and onion-domed churches, added to the mystery as did the

impression of a land mostly gripped by the severe weather of long

winters.

Hakluyt’s Voyages

give us a glimpse of the Russia of the middle ages. Richard Hakluyt was

a clergyman and geographer in the time of Queen Elizabeth, Walter

Raleigh and

Francis Drake. He took a life-long interest in the voyages of early

explorers and captains of merchant ships, and collected the accounts now

published in the classic book that bears his name. Much of the record

consists of the actual voyage logs and reports by those intrepid sea

captains. Hakluyt untiringly assembled information and minutely

detailed sailing directions for various parts of the globe. Some of the

expeditions of English merchant ships to Russia border on the

incredible. Those relatively small sailing boats went north past Norway

and east through the Barents Sea to Archangel, and from there up-river

to near Moscow, then overland to the Volga river, then south to the

Caspian Sea, and across it to trade with eastern merchants. After all

that, the whole journey had to be repeated in reverse. In one of the

accounts, a captain who suffered all sorts of dangers, several times

nearly losing his life and all the cargo, says at the close of his

report, in massive under-statement, that he “hoped his employers

appreciated all he endured to ensure a profitable investment for them”

!

Above: a page from Hakluyt’s

“Principall Navigations”, 1589,

his book of voyages of exploration and early trade routes by English

ships.

The Russian people and

their satellite citizens have come through long periods of severe

hardship from the elements, from famines, from wars and from oppressive

rulers, - first the Tsars and Emperors, and later the Soviet dictators,

- Lenin, Stalin, Bulganin, Kruschev, Brehznev, and others. Kruschev I

have a soft spot for. He was different from the staid, sullen,

doctrinaire leaders of Russia’s communist governments, and actually

began the process of de-Stalinisation of the country. But no doubt he

was guilty of much also.

From my youthful

fascination with aircraft, I was to develop a strong interest in space

flight and recall the news we received in October 1957 that the Russians

had successfully launched the world’s first artificial satellite,

“Sputnik 1”. The Daily Express headline next day said it all :

“Midnight - and London hears the first signal – Space Age is Here !”

On the 12th

April 1961 (on a fine day) we were fishing on Stormy Bank to the

west of the Orkney Islands. The cook served up lunch and when we went

below, my father announced that the Russians had put a man in space. I

asked with some concern how they were ever to bring him back to earth

again, but was assured that he had already returned safely. The

spaceman was Yuri Gagarin, and his craft was called Vostok 1.

The spaceship had made a single orbit of the earth and was brought down

in Kazakhstan. The event caused world-wide excitement, and some

consternation in the USA where President Kennedy committed substantial

funds to the American space flight programme. Sadly, Gagarin

himself was to die in an airplane crash in 1968 while training for the

Soviet space station programme.

The Russians launched

Vostok 2 four months later, with Gherman Titov on board. This

craft orbited the earth 17 times. The following year Vostok’s 3

and 4 were launched. They remained in orbit for 3 and 4 days

respectively. 1963 saw Vostok 5 and 6 launched, the

latter containing the world’s first woman astronaut (or cosmonaut),

Valentina Tereshkova. The Vostok programme was then terminated

and replaced by the Voshkod programme that involved a 3-man

spacecraft.

Yuri Gagarin, first man in space, April

1961

The first American

orbital space flight was in February 1962 when John Glenn took his

Friendship 7 Mercury capsule on a 3 orbit flight. The previous year

there were two sub-orbital flights of 15 minutes duration that reached a

height of 116 miles above the earth. By May 1963 there were 3 more

Mercury flights, the longest lasting 34 hours. The Gemini

2-man capsule programme began next and between March 1965 and November

1966 there were ten Gemini flights, the longest one lasting

nearly two weeks. The Russian Soyuz space staion programme began

in 1967 and lasted till 1977. The American Apollo programme

started in 1968 and continued till 1975. Six Apollo flights

successfully landed men on the moon (in 1969, 1971, and 1972).

Russian progress in

science and technology lay in contrast to the brutal control of the

Soviet satellite states, and was becoming evident in the suppression of

all kinds of dissent within Russia. The gulag prison camps that

stretched all over the continent from around Moscow to inside the Arctic

circle, and east across Siberia, were full of political prisoners and

other dissidents whose only crime was to express their sincere

thoughts. There were also thousands of innocent victims of the system

who were given ten year hard labour sentences on trumped up charges,

simply to create fear or to “encourage les autres”.

In 1956 Hungary

attempted to throw off the Soviet yoke. Growing resentment of the

foreign control erupted into a national uprising in October of that

year. Within a few days there were 2,000 Soviet tanks in Budapest and

other cities. Hundreds of citizens were killed, many imprisoned, and

suspected leaders were executed. Communist control was reestablished,

though with a new awareness that people’s aspirations could not be

completely ignored.

Another East European

country tried to extricate itself from Soviet control in 1968 when a

liberalization programme was led by national communist leader Alexander

Dubcek. It was to be known as the “Prague spring”. But like the

Hungarian revolt, it also met with fierce opposition from Moscow, though

this time there was an attempt to downplay Russia’s role by the use of

Warsaw Pact forces to crush the liberalization movement and to restore

the “orthodox line” to Czech politics and government.

I was to visit the Soviet Union in 1965, participating in a

United Nations FAO seminar and study tour on fisheries education that

took us to Moscow, Murmansk and Kaliningrad. We were treated warmly by

our Russian hosts, and shown kindness and hospitality by all the people

we encountered. Contrary to western impressions there was no apparent

attempt to restrict our movements, and I was able to attend Sunday

services at the large Moscow Baptist church. Later in 1996, I spent

some time in a former Soviet State, then independent Turkmenistan,

located just north of Iran and east of the Caspian Sea.

Map of Russia

Moscow and the Kremlin

In between those dates I became an avid reader of the works

of Alexander Solzhenitsyn beginning with “One day in the Life of Ivan

Denisovich”, and on through Matriona’s House, Cancer Ward, The

First Circle, Lenin in Zurich, August 1914, and The Gulag

Archipelago. I devoured all 3 volumes of The Gulag, but have

yet to meet another person who lasted the distance. I found many who

read Volume 1, a few who managed to read Volume 2, but none who read all

three. It is a pity as Volume three is the best of the series. It is

the one that paints the picture of the hope and triumph of the human

spirit against impossible odds. The most moving chapter is “Truth

under a tombstone; poetry under a stone”.

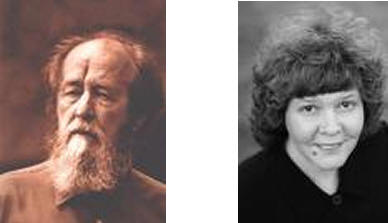

Alexander

Solzhenitsyn, author of Irina Ratushinskaya, Russian

dissident poet

The Gulag Archipelago

|

Alexander

Solzhenitsyn and Irina Ratushinskaya

Just over 50

years ago, one cold night in a Soviet prison camp outside of

Moscow, a woman prisoner was being made to stand outside by the

barbed wire fence, for some minor infringement. Her pleas to be

allowed back into the barracks for shelter and rest were ignored

by the sullen guard. On the other side of the fence, in the

men’s section, a ‘zek’ or prisoner was sweeping up leaves and

putting them into a brazier fire. “Woman”, he said under his

breath, “I swear to you, by these leaves and this fire, that one

day the whole world will read about you!” The ‘zek’ was

Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a former artillery captain in the Red

Army, who had been decorated for bravery, but was imprisoned for

criticizing Stalin in a letter to a friend in 1945.

During his 8

years in the Gulag prison camps, and 6 years in exile in

Kazakhstan, Solzhenitsyn collected thousands of pieces of

evidence from documents, oral testimonies, eyewitness accounts

and other material, on the brutal injustices of the Soviet

regime. Much of the material he put into verse since he could

not be sure that written notes would not be found. When he

finally left prison, he was thoroughly searched, but the guards

could not see or remove the poetic evidence in his mind. After

his exile he settled in a lonely Siberian village of Riazan

where he worked as a teacher.

While there he

began to document the evidence on paper, eventually compiling

the 3-volume Gulag Archipelago 1918 – 1956. One of the first

short stories he managed to get published in Moscow was

‘Matryona’s House’. During this time he also wrote ‘One day in

the Life of Ivan Denisovich’ which was published in 1962,

surprisingly at the instigation of Nikita Kruschev who had

decided the time was ripe to start telling the truth about

Stalin. ‘The First Circle’ and ‘Cancer Ward’ followed in 1968,

but Leonid Brezhnev’s government was less sympathetic. They had

him expelled from the writer’s union in 1969, and deported from

the USSR in 1973. He had been awarded the Nobel prize in

literature in 1970, but was not able to collect it till 1974.

Some in the West

have difficulty understanding Solzhenitsyn, - his fierce moral

outrage, and his skepticism towards aspects of western

liberalism and materialism. He is a Russian patriot in the

tradition of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Like them, he is a

chronicler, a witness whose experience is part of the way to

approach truth and judge events. Much of Western democracy he

regards as spiritually exhausted, and claims that the sufferings

of the Russian people under communism have taken them through a

spiritual training far in advance of Western experience.

Solzhenitsyn

believes that mediocrity triumphs in the West under the guise of

democratic restraints. He also criticizes Russia’s embrace of

the worst aspects of capitalism, and calls his country back to

its spiritual roots. These are typified in the story of the

peasant woman Matryona whose life of toil had been full of

disappointments but who maintained her integrity through it

all. In the book he says that it was long after she died before

he realized who she really was. “We had lived side by side, and

never understood that she was that one righteous person without

whom, as the proverb says, no village can stand. Nor any city.

Nor any country.”

For those who

find Solzhenitsyn a bit heavy, there is another Russian

dissident who conveys a similar message, but with a beautiful

innocence of heart, and complete lack of hatred towards the

perpetrators of institutionalized cruelty. She is Irina

Ratushinskaya, a poet, who spent years in prison for simply

writing about truth and beauty. Her two books are “In the

Beginning”, and “Grey is the Colour of Hope”. [Grey

is the Colour of Hope,

and

In The Beginning, by Irina Ratushinskaya,

translated by Alyona Kojevnikov, and published in 1988 and 1990

by Hodder and Stoughton, Sceptre Books, Sevenoaks, Kent,

England.]

It never ceases to amaze me, that even in cruel totalitarian

regimes, with their extreme efforts to control information and

free thought, that there arise men and women who refuse to

submit to political idolatory, or to eat its meat. They rise

like rare flowers in a desert, or as Solzhenitsyn described

them, like heads bobbing up to the surface of a misty sea after

a storm. We are yet to hear from most of them, but I am sure

there are many, living or dead, who have borne witness to the

truth despite brutal repression, in China, North Korea, Burma

and other dictator-ruled states that through much of the last

century have sought to keep the people subject to their control,

and ignorant or misled about the truth.

|

Ratushinskaya’a poetry

does not translate too well, but here are two extracts from her book,

Grey is the Colour of Hope, written in 1986:

“In the (convict railway) carriage, the fact that I am a ‘political’

arouses much interest. I have to explain everything from scratch yet

again : about human rights, about my poetry, then read my poetry – to

the whole carriage. The guard is clearly interested, too, for he makes

no move to stop me. … I read on : what price I and my poems if I can’t

get through to this audience ? Too many of us have been too far

‘removed from the people’ already. …

The guard (they’ve changed shifts again) utters a word of caution :

“Be quiet for a bit, the boss is about due to come around.” And

once his senior has been through, he prompts me, “Go on, what else is

there?” I do go on. Who needs this more than you in uniforms, be

they zek [ “Zek”

is the Russian term for a convict.] uniforms or military ones? Not all of you are lifelong

thieves and bandits.

Your lives have been disfigured, but your souls are intact. How do your

souls fare, hammered by the machinery of lies and violence from early

childhood ? How wonderful if they do not succumb, but is there any

chance of that ? I continue to hope that there is. … … …

You must not under any circumstances allow yourself to hate. Not because

your tormentors have not earned it. But if you allow hatred to take

root, it will flourish and spread during your years in the camps,

driving out everything else, and ultimately corrode and warp your soul.

… If you can spot no spark of humanity in (the KGB and Gulag guards),

no matter how hard you try, remind yourself that cockroaches are

exterminated without hatred, rather with a feeling of revulsion. And

‘they’ – armed, well-fed and belligerent – are like vermin in our big

house, and sooner or later we shall get rid of them and live in

cleanliness. Is it not pathetic that they have designs on our immortal

souls.

All this in sum brings about one marked change in your physical

appearance : by the end of your first year, you will have what are

known as ‘zek’s eyes’. The look in a zek’s eyes is impossible to

describe, but once encountered it is never forgotten. When you emerge,

your friends embracing you, will exclaim : “Your eyes ! Your eyes

have changed !” And not one of your tormentors will be able to

bear your scrutiny. They will turn away from it like beaten dogs.”

Unlike the works of the

dissidents, Russian novels can be heavy, and some of the music can be a

bit dull. But the Cossack dancing, - now that is something exciting. I

am sure that it must be the most exhausting form of group dance of any

in the world. And there is one musical instrument that can be

excruciatingly beautiful to listen to. I was in the Kremlin theatre with

our group, attending a variety show that had a bit of most kinds of

Russian culture. Towards the end a well-known local musician came on

stage and sat down to play his balalaika. The lights went out and a

single beam focused on the minstrel. He started to play, the strings

vibrating so softly and at such high pitch, you could scarcely hear,

then the volume increased as he developed the melody, and the music

filled that large theatre to the delight and appreciation of all

present.

Russia in 1965 was

still living very much in an immediate post-war atmosphere. To me it

resembled Britain of the 1945 – 49 period. There was a lot of visible

war damage around still awaiting repair, and the people regarded Germany

as the enemy to be feared. The word ‘enemy’ was used to me by the

interpreters only of Germany and China, not interestingly then, of the

USA. The post-war atmosphere was also evident in their showing us a

propaganda film of the war, and taking us in Kaliningrad to a bunker

where the last few SS soldiers held out till they were all killed. It

had been preserved exactly as it was found.

Myself in Russia with an international

group, 1965

Murmansk in the frozen north of Russia

On our return to Moscow

from Kaliningrad and Murmansk we were put into a different hotel which I

was told by those who knew, was standard practice for foreign visitors.

The first night our group was invited to a ballet performance. I

declined together with a Singapore colleague, and one of the

interpreters agreed to stay with us. An East German chemical exhibition

being held near the hotel.

As we wandered down the

road, we were accosted by a small but very drunk Russian man who

demanded to know if we were German. We had difficulty convincing him we

were not as he realized that we were definitely not Russian. He said

that the Germans had killed his father and he was going to take his

revenge on them. He had difficulty identifying the country of my

Singaporean friend but then associated him with the only Indo-chinese

country he knew – Vietnam! He threw his arms around my startled

colleague and began to apply full-blooded Russian kisses on his mouth.

We pulled them apart and ran up the road, ducking into a side street

till our little drunk friend passed, then we walked briskly back to the

hotel. The group bus had just arrived back from the ballet. The party

came out in leisurely fashion and stood in the fore court getting some

fresh air. We ducked inside a doorway as we saw our amorous

acquaintance come staggering back. He went up to the group, who were

blissfully unaware of his intentions, and picked out a dusky Pakistani

officer. As we beat a hasty retreat inside, the last we saw was two

strong colleagues vainly trying to prise our friend off the astonished

Pakistani who was being kissed as never before in his life!

Our conversations with

interpreters and other Russians left me with some interesting

impressions. One interpreter, Vassily, had been trained as an artillery

officer during his national service. He told me, “David, I hope I

never have to use that skill”. Russians love to joke, and their

humour is very earthy. In some ways they resembled Aberdeenshire Scots

to me. They discussed politics and world affairs with surprising

frankness since the country was still under totalitarian rule. And they

also displayed an eager interest in religion and the Christian faith in

particular. Most of the interpreters at one time or another, came to my

room and asked if they could see my Bible. They said there were many

believers in Russia, including some in high position, naming a few, but

they were not people with whom I was familiar. One Sunday we were

invited to watch Moscow Dynamo versus Spartak in a local derby football

match. I asked if I could attend a church instead. This was readily

permitted, only they said I would have to find my own transport, and

they could not spare an interpreter. However, the hotel kindly gave me

the address and time of service, and I got a taxi to take me there. It

was a moving experience to be in the Moscow Baptist church with two

thousand local worshippers including a surprising number of young

people. The church provided me with an interpreter, and even had my

greeting read out to the congregation. The service continued for two

hours, and I was given a lift back to the hotel by two of the members.

Nikita Khrushchev had

been replaced as Soviet leader, a year before my Moscow visit, by

Brezhnev and Kosygin who ran the Soviet Union for more than a decade

till Brezhnev was replaced after his death by the aging Andropov, who

was to be succeeded by the aging Chernenko. Despite his histrionics at

the U.N., and his often bellicose statements, I warmed to the bluff,

peasant-like Khrushchev who at least exhibited some colour, in contrast

to the dreary line of post-Stalin leaders. He also was the first to

publicly denounce Stalin for his dreadful purges, and to permit a degree

of press freedom that led to the emergence of dissident writers like

Solzhenitsyn who till then could only publish under the samizdat

underground informal press. On taking power, Leonid Brezhnev soon

stamped on the fragile shoots of freedom that Kruschev had permitted.

I believe it was in

late 1984, when my wife and I were walking through Edinburgh’s west end,

that we were surprised by an unusual event in Scotland, - a very large

motorcade of police cars and motor-cycles coming from the direction of

the airport. Two or three limousines drove past with the police escort,

and headed into Princes Street, but we were unable to recognize the

occupants. Later we discovered in a surprisingly brief news item, that

the visitor given such large police protection, was a Soviet politician

by the name of Mikhail Gorbachev. He of course went on to become the

Soviet leader, and was described by Mrs Thatcher as “a man with whom

we can do business”. He was to be the architect of the

modernization and opening up of the Soviet Union with his policies of

glasnost and perestroika. Surprisingly, Gorbachev did not

appear to realize himself what the policies would lead to, or how they

would open the door to forces he could not control. I personally was

sure he committed political suicide when following the attempted coup

that involved his abduction, he defended the Communist Party. His

failure to read events accurately, or to fully appreciate the public

reaction, led to his fall from power, and the rise of Boris Yeltsin.

This brought an end to the mighty Soviet Union, and ushered in the

Russian Federation, leaving a number of satellite states to pursue their

own course.

Since then the Russian

Federation has withdrawn somewhat from the rather chaotic measure of

democracy and transparency brought in by Yeltsin’s government. A former

KGB chief, President Vladimir Putin, now maintains an iron grip on

Russian institutions and the Federation states, just I suppose, as in

the USA, a former CIA Director, George Bush senior, and now his son,

George junior, has led the United States back down an extreme right wing

and imperialist path. Putin’s absolute refusal to countenance any form

of self-rule for Chechnya has resulted in a blood bath both inside and

beyond that state. Russia’s political and economic decline may have

bottomed out as the Federation begins to discover the power it can wield

from its massive gas and oil reserves, its proximity to the Middle East

and Central Asian states, and the overhaul of its nuclear arsenals. But

there are sinister repeats of past brutality being seen in the ruthless

and brazen murders of brave news reporters and dissidents – even beyond

Russia’s borders.

One of the worst and

most blatant acts of suppression of free speech was the murder of

newspaper reporter Anna Politkovskaya. This brave and determined

investigative journalist had exposed much of the brutality, torture and

injustice in Russian suppression of Chechnya. She was gunned down in

her apartment block in Moscow in October 2006. Together with the murder

of Alexander Litvinenko in London the following month, it was indicative

of a callous tough new attitude to dissent by the Kremlin authorities,

reminiscent of the worst periods of Soviet rule.

Anna Politkovskaya, investigative

journalist, murdered in October 2006

While welcoming the

demise of the Soviet Union and its record of cruelty, dictatorship and

mismanagement of the economy and the environment, some informed

observers believe that the emergence of the USA as the world’s sole

super-power is not a healthy situation. It has lead to the GW Bush

government invading foreign states imposing its will, and ignoring human

rights and international justice, while neglecting the less affluent of

its own people at home. Since the fall of the Soviet empire, the

salaries of corporate executives have risen ten times more than those of

the lower paid in the USA. There have been huge tax reductions for the

most wealthy, windfall profits for the big corporations, and a relative

decline in health entitlements, welfare allowances and social services

for the poor. There have also been a surprising number of financial

scandals involving the theft or illegal manipulation of billions of

dollars of investors and taxpayers money. However those factors are

genuinely related or not, it would appear that the fear of communism or

socialism reducing support or rationale for the capitalist system,

seemed to place a check on the excesses of the USA while the Soviet

Union continued to be a global super-power. Now that the threat is

gone for the present, we see re-emerging the behaviour of some of the

worst or most extreme elements of U.S. capitalism.

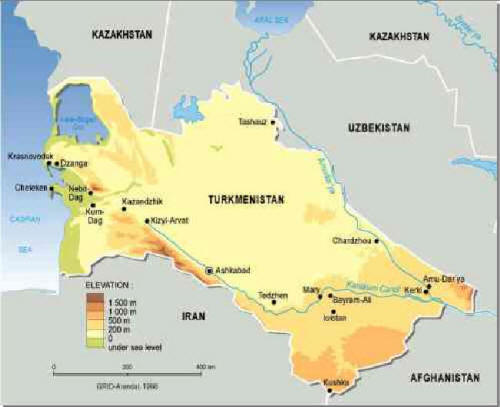

Turkmenistan

At the southern border

of the former Soviet Union, and facing both Iran and Afghanistan to the

south, lies the state of Turkmenistan. It was made a member of the

Soviet Republics in 1925, and stayed within that orbit till it obtained

its independence in 1991 after the break-up of the USSR. I was to

assist a team that had been provided by the European Union Tacis

programme to help the former soviet satellite on the road to

privatization. Two strong impressions remain with me from that

assignment. The first is the character of the ancient Turkmeni people

whom one could not help admiring, and the other was the nature of the

independent government, - centrist, totalitarian, and built around a

personality cult. My Turkmeni driver, Kurban, a strong, energetic and

reliable man, wept like a child when we said goodbye at the airport on

my final departure.

Map of Turkmenistan

The country is an

enormous desert, the Kara-kum (black sand) desert, stretching from the

Caspian Sea to the Amu Darya river. The population of just under 5

million is mainly Turkmen, with perhaps 10% of Russians, and a

sprinkling of Uzbeks and others. The natural resources include

petroleum, gas, sulfur and salt, and its agriculture produce is mainly

cotton and rice. Fish, both kilka sprat and sturgeon, are

produced from the Caspian Sea where the country has a port, formerly

Krasnovodsk, now Turkmenbashy after the invented national name of

President Saparmurat Niyazov. The capital city Ashgabat, is a mixture

of soviet and central Asian architecture, some of it bizarre to western

eyes. It was built on the site of a Russian fortress dating from 1881.

Ashgabat was destroyed by an earthquake in October 1948. Over 120,000

of its inhabitants perished in that disaster. The modern city was built

with wider streets and buildings more spaced out to minimise possible

future damage from quakes.

The Kara-kum desert

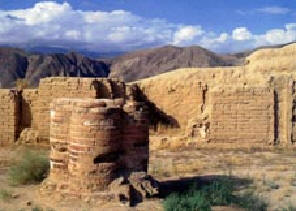

Not far from the

capital, half-buried under desert sands, lie the remains of the once

huge city and fortress town of Nisa which was the capital of the

Parthian empire from around 300 BC till 300 AD. It may have been the

site of an earlier Persian fortress built 2,500 years ago by Darius the

Great. Modern Persia, Iran, lies only a few score of miles to the

south. 90 kilometres west and close to the border with Iran, at

Bakharden, there is an underground hot spring lake called Kov Ata inside

a vast cavern. I found it weird to be swimming down there in the warm

sulfuric water, far below the ground, together with my Turkmeni driver

and Russian interpreter. Following our subterranean bath, my Turkmeni

driver took me and Ellena the Russian interpreter, to a pleasant

location by a stream in a mountain pass where he lit a fire and grilled

shish’ kebabs for our picnic meal.

Ruins of the ancient fortress of Nisa

Only 3.5% of the land

is arable, and even that is cultivated only by water extracted from the

Amu Darya river, and led by canals to the cotton growing areas and small

farms. This is the source of huge environmental problems, not just for

the country, but for the whole region. Western industrialization and

agricultural mechanisation has created dust bowls in central America,

and areas of pollution around our cities and factories. But Soviet

industrialization and central control of agriculture has shown even less

concern for the planet’s life support system. The great Aral Sea

located between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan was once the fourth largest

inland sea in the world, covering over 25,000 square miles and

supporting a large fishing industry. It has now shrunk to less than a

third of its size and this reduction is bringing ill-health,

unemployment, and food shortages to the region. The salt content of the

sea has doubled, and winds now carry salt and sand from the dried-up

areas, depositing it around within a 300 km radius, destroying pastures

and adding to deserts and toxicity.

Above :Turkmeni women in national dress

in Ashgabat. (the picture had to be taken surreptitiously as neither

people nor police like foreigners to do this).

Even Turkmenistan which

is chiefly, but not solely to blame for the diversion of fresh water, is

suffering the consequences in salination of its surface water bodies,

residues of chemicals and pesticides in its soils, and pollution of the

huge Caspian Sea. In hindsight it is easy to see that cotton was a most

unsuitable crop for a region with so little fresh water; but it became a

major export earner, making Turkmenistan the tenth largest cotton

producer. So it is difficult for any administration to reverse the 40

year policy, to dismiss thousands of workers, and to substitute with

other environmentally friendly industries. Like most of the world’s

environmental problems, there are no short-term solutions, and few

governments are prepared to inflict the pain necessary to achieve the

long-term gains.

The resilience of the Turkmen people and the Russian

residents, in struggling to make a life in adverse circumstances is

admirable. Their struggle is made all the more difficult by a

government that has retained most of the worst aspects of Stalinist rule

and controls. To take one example, the manager of the processing plant

and fishing fleet on the Caspian Sea, was working wonders to pay his

work force, keep the vessels operating and produce the canned and frozen

fish the country needed for food and exports. This was against the

background of restrictions placed upon the operation. No worker could be

dismissed, and the plant had to supply free fish to the army and the

hospitals. State supplied budgets were invariably inadequate. The

manager became an expert in robbing ‘Peter to pay Paul’. He bartered

fuel oil to pay Russian shipyards to overhaul his vessels, and bartered

fish to get metal plate to can the next lot of sprats. What was his

thanks ? A bureaucrat came down from the capital to inspect the books.

He said that the manager was not acting according to the rules and had

him arrested and imprisoned.

Sturgeon fishing in the Caspian Sea

The Government was committed on paper to de-nationalisation

and privatization, but officials appeared to have little concept of what

that meant. We asked one senior officer to explain how it would work

out in practice. He said that the State would retain 51% of the shares

of any company. A private sector firm buying into the industry would

have to pay the State a high price for the 49% of shares on offer. They

would then be expected to invest heavily to renovate the factory, though

plants were in such bad shape, it would be easier and cheaper to build

new. The new managers would have to retain all of the existing work

force, and to continue to supply free food to the army and the

hospitals. On top of all that they would be expected to produce a

healthy profit for the government. Small wonder then that privatization

has proceeded at a snail’s pace in that land.

It is all so

depressing, and even more so when there are some possibilities to put

the country on a path to economic progress and environmental

rehabilitation. The people are hard working and willing to endure much

deprivation to carve out a future for their families in the rugged

desert lands of central Asia. During my stay I was privileged to share

the hospitality of the Turkmen people in their own homes. It was rather

eastern in form. We sat on the floor on Persian rugs, and helped

ourselves to food from an array of local produce and Turkmen cooking.

On several occasions I was generously entertained by my Turkmeni friends

who made

shish’ kebabs on charcoal fires with mutton meat, onions, large peppers

and tomatoes, over which they poured vinegar as it cooked. On the

Caspian Coast my Russian hosts did the same with sturgeon meat.

In the

nine years since my time in Turkmenistan, the President for life

continued to reinforce his ruthless steely grip on power, practically

isolating the country from the rest of the world. His paranoid control

of the country extended beyond political dissent to social and religious

activities. Though he permitted the Russian Orthodox church and the

small local Roman Catholic church to continue to function (possibly

because the Vatican was seen as powerful politically), he suppressed

other bodies. A Russian baptist house church was bulldozed to the

ground. The local population is officially unaware even of events in

neighbouring states, like the popular uprising in Kyrgystan, that has

deposed the former President there, and his indifferent regime.

Saparmurat Niyazov had become communist party chief in 1985, and held

the offices of President, Prime Minister, and Commander in Chief till

his death in late 2006. He had renamed himself ‘Turkmenbashi’, meaning

‘father of all Turkmen’.

Now the

whole Caspian Sea region has acquired global strategic importance due to

its enormous reserves of natural gas and petroleum. These resources are

distributed in a region that is difficult to access and to export from

due to its remoteness and to the political tensions and differences of

the region’s states. Nevertheless, the USA, Europe, Russia and China,

are assiduously courting the governments of Azerbaijan, Kazakstan,

Turkmenistan, and others, to obtain supplies and to build pipelines that

would carry the oil overland and on to the Black Sea or the Persian

Gulf. One current proposal is for a pipeline from Turkmenistan to

travel west under the Caspian Sea. The gas reserves which exceed oil

resources in the region, are much more problematic to extract, store and

transport.

My late

Icelandic friend Hilmar Kristjonsson who led our study tour visit to the

USSR, used to say that culturally the orient began on a longitude

somewhat to the west of Moscow, which I think sheds some light on

aspects of Russian life. It reflects a statement attributed to

Napoleon, “scratch a Russian, and you’ll find a Tartar underneath”.

Another

friend and colleague, Menachem Ben Yami, who fought with the Red Army

during the war, and spent some months in Moscow, used to say, “never

underestimate the Russian”. I often recall that statement as the

vast country goes through its current turmoil. The Russian people will

endure, they will persevere, and they will emerge from it all,

hopefully, stronger and progressing to a degree of peace and plenty.

During

my first visit to Soviet Russia, our group attended a series of

receptions at which there were the obligatory toasts. The first toast

always was to “Mir”, - to peace, and to friendship. It was the

diplomatic norm, but I often felt I detected genuine sincerity in the

persons proposing the toast. They were invariable prematurely aged from

the efforts to re-build the country after the war, with limited

resources, and under a ruthless regime, - but build it they did, and on

meeting visitors from abroad, they wished them only peace. |