|

When sunrays crown thy pine-clad

hills

And summer spreads her hand

When silvern voices tune thy rills

We love thee, smiling land

We love thee, we love thee, we love

thee Newfoundland.

When spreads thy cloak of shimm’ring

white,

At Winter’s stern command,

Thro’ shortened day and starlit night,

We love thee, frozen land,

We love thee, we love thee, we love

thee, frozen land.

When blinding storm-gusts fret thy

shore

And wild waves lash thy strand

Thro’ spindrift swirl and tempest roar

We love thee, windswept land

We love thee, we love thee, we love

thee windswept land.

Newfoundland anthem, Sir Cavendish Boyle

My first impression of

North America was to be in the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It

proved to be an enriching experience in many ways despite the Province

being the butt of many jokes on the Canadian mainland. I recall the

words of a Canadian couple I spoke to in Prestwick airport Scotland, as

I waited for my flight to depart in October 1965. They said “oh,

Newfoundland, - the cold, the mist, the snow, the parochialism, the

isolation, - and we can assure you, - you will love it!” They were

absolutely right. ‘Newfy’s’ make up for all the disadvantages of their

island community with a wonderful spirit of friendliness, humour, love

of music, openness and hospitality.

Mainland Canadians are

surprisingly ignorant of Newfoundland which is in many ways more

cultured and better developed than some parts of the other maritime

provinces. Eskimo and Indian peoples inhabited the area for many

centuries, and there appear to have been brief settlements of Viking

sailors in pre-Columbus times, though evidential remains are scanty.

The first recorded European visitor was in 1498, when John Cabot of

Bristol arrived (or was he Jean Cabot of France? or Giovanni Cabotto of

Italy! – it is not certain). So that part of Canada has been exposed to

European fishers and traders for over 500 years. Newfoundland was

proclaimed an English colony under Queen Elizabeth 1st in 1583 by Sir

Humphrey Gilbert, but that ill-fated explorer lost his life on the

return voyage across the Atlantic. Cornish and west English fishers

began to establish stations on Newfoundland’s east coast from the 17th

century. The British Government was not keen however to see an

indigenous fishing industry established, since it would compete with

English merchants, and for many years, each autumn, the British navy

burnt settlements established near the shore by fishers who may have had

visions of spending the winter there. See St John’s magnificent harbor

below :

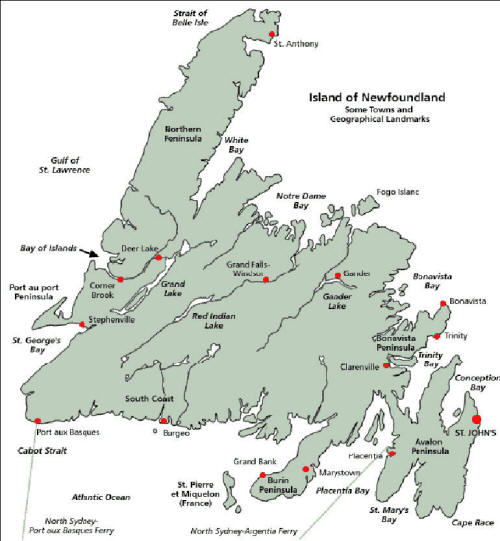

map of Newfoundland

When I arrived, Portuguese sailing schooners were still

fishing for cod in the summer months. These beautiful vessels often

came into St. John’s harbour where they were a colourful sight.

American and Canadian dory fishing had all but ceased, but those

intrepid Portuguese sailors went off from their schooners in little

one-man and two-man dories, hand-lining for cod on the Greenland

grounds. The fish caught were split and salted, and taken back to

Portugal to be further dried and sold as stockfish. The type of fishing

was described by Rudyard Kipling in Captains Courageous, and

pictured in the Spencer Tracy film of that novel. Cod fishing by

Newfoundland fishers in the 1960’s was by means of the cod trap, a

box-shaped net with a short leader, set next to the shore or cliffs, or

by baited long-line, or otter trawl. Some old British side trawlers had

been procured by local companies, and a fleet of new steel stern

trawlers was being steadily built up.

Newfoundland dory (used

for cod fishing) St Johns natural harbour

The famous Grand Banks

of Newfoundland were already fished out by the 1960’s, and cod stocks

had moved to the north-west and north-east. Some fishers and scientists

believe that the current absence of cod off Canada’s east coast owes

more to global warming of sea temperatures, and to the cod seeking

colder waters, than to over-fishing by local fleets which was the

government’s conclusion. But in the 1960’s though cod were still

around, they were mostly found off Labrador to the north. During the

spawning season however some schools still entered the Newfoundland bays

where many were still trapped in the local fish traps set for that

purpose.

Farther north, the larger and sparsely populated part of the

Province, was wild Labrador, where Newfy sealers went to fish each

winter or spring. This remote and forbidding land was the scene of the

life’s work of Dr William Grenfell, a remarkable missionary and

pioneer. He had served with the British RNMDSF fishermens mission on

the North Sea in the late 1880’s but heard that a greater challenge and

greater needs existed in Labrador. So Grenfell took up the call, and so

served that province and its people, that today no name is more revered

in Labrador, than that of the humble, persevering doctor.

postage stamp of Sir Wilfred Grenfell

Dr Grenfell and his Labrador mission boat

I lodged with a local

family the first

year, in the appropriately named Topsail Road, and enjoyed

a rich fare of home-baked bread, local berries, and meat from moose,

rabbit, seal, seabird and whale. The seal and whale meats were too

strong for me, but the ‘flipper pie’ was palatable. Surprisingly fish

were not often on the menu. In the 1960’s there was not a single fresh

fish market in St. John’s, only the occasional sale of cod from a

wheelbarrow in Water street, by fishers from the nearest cove. And the

frozen fillets of cod, flounder and redfish from local fish plants were

abominable to say the least.

Newfoundland had a

thriving stockfish (dried, split, salted cod) trade up till 1960, for

which there was and is a ready market. The most lucrative market was in

the Iberian peninsula, the next in West Africa, and the lowest quality

went to the Caribbean. Some bright fishery administrator abolished the

quality grading of stockfish. The general quality then bottomed out,

and at times was not even acceptable on the cheapest markets. For all

its fishing history, the Province’s industry of that period, was in a

dismal condition, which was one reason the Fishery College was built,

and I was offered work there for two years.

Newfoundland

then had a dynamic Premier, Joey Smallwood, who had great vision for his

Province having fought successfully for it to undertake the step of

Confederation with Canada. He was constantly on the lookout for new

investment and new industry. But like many isolated island communities,

Newfoundland was regularly taken advantage of by fast-buck merchants and

pretending investors who had other agendas. One of the biggest

disappointments was the Churchill Falls hydro-power dam in Labrador.

The project was planned during my stay, and came on stream just before

the OPEC oil crisis and the global rise in energy prices. The Province

found itself locked into a contract by Quebec that gave it so little in

return for the electricity, Newfoundland was actually subsidizing the

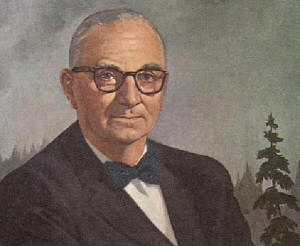

richer mainland provinces with valuable energy. Above left :Joey

Smallwood, Newfoundland’s dynamic Premier Newfoundland

then had a dynamic Premier, Joey Smallwood, who had great vision for his

Province having fought successfully for it to undertake the step of

Confederation with Canada. He was constantly on the lookout for new

investment and new industry. But like many isolated island communities,

Newfoundland was regularly taken advantage of by fast-buck merchants and

pretending investors who had other agendas. One of the biggest

disappointments was the Churchill Falls hydro-power dam in Labrador.

The project was planned during my stay, and came on stream just before

the OPEC oil crisis and the global rise in energy prices. The Province

found itself locked into a contract by Quebec that gave it so little in

return for the electricity, Newfoundland was actually subsidizing the

richer mainland provinces with valuable energy. Above left :Joey

Smallwood, Newfoundland’s dynamic Premier

The College of

Fisheries, Navigation, Marine Engineering and Electronics, was one of

Premier Smallwood’s projects. It was housed in the former Memorial

University buildings when that institute moved to a new campus. The

main building appears in an earlier Newfoundland postage stamp issued

before Confederation with Canada. President of the College was Dr W. F.

(Bill) Hampton, a former food technologist who was credited with

development of the first “fish fingers”. There were both national and

international staff in the five college departments. Two of my

colleagues in Nautical Science were marvelous seamen, - former masters

of schooners, Captain Williams and Captain Burden. Captain Williams’

seamanship room was one of the finest I have seen anywhere, with

examples of every kind of rope-work, wire-work and ship’s rigging. My

direct co-lecturer was Professor Yunosuke Iitaka from Kinki Unuversity,

Osaka, Japan. He was a splendid example of the fishery academics

produced by the then leading fishery country in the world.

Postage stamp showing the old Memorial University in St John’s which

became the new College of Fisheries in 1964. (The College was later

moved and was transformed into a new Marine Institute. The old building

now houses a technical school)

A fascinating staff

member in our Department was Otto Kelland, a well-known local musician

and song-writer. The college had hired him for his skills in making

model boats, but he was more renowned for his musical talents. All who

know Newfoundland will be aware of its rich heritage of sea shanties and

folk songs, mostly with an Irish lilt to them. Otto’s finest production

was Cape St. Mary’s, written in 1945. The music which is

truly moving, you will have to locate elsewhere, but I cannot resist the

temptation to include a few verses here.

Take me back to my western boat, let me fish

off Cape St. Mary’s

Where the hag-downs sail, and the fog-horns

wail,

With my friends the Browns and the Cleary’s,

Let me fish off Cape St. Mary’s.

Let me feel my dory lift, to the broad Atlantic combers

Where the tide rips swirl and wild ducks whirl.

Where old Neptune calls the numbers

‘Neath the broad Atlantic combers.

Let me sail up Golden Bay, with my oilskins all astreamin’

From the thunder squall when I hauled my trawl

And my old Cape Anne a-gleamin’,

And my oilskins all a-streamin’.

Let me view that rugged shore, where the

beach is all a-glisten

With the capelin spawn, where from dusk to dawn,

You bait your trawl and listen,

To the undertow a-hissin’.

Take me back to that snug green cove, where

the seas rolls up their thunder,

There let me rest in the earth’s cool breast

Where the stars shine out their wonder

And the seas rolls up their thunder.

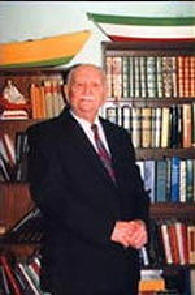

Otto Kelland the composer of Cape St.

Mary’s who died in his hundredth year. He made beautiful models of

schooners and fishing boats for the College when I served there.

Newfoundland had its

“city” people and its “bay” people, and you had not arrived till you had

stayed a few days in one of the many out-ports where houses were mostly

built on pole frames above the ground. Practically every second

Newfoundlander then was a skilled carpenter and could build a timber

frame house, as his wife could bake bread. (No self-respecting

Newfoundland wife would buy bread, - only flour. Bread was what

incomers and some city people bought!). To spend a week-end at an

outport was to experience generous hospitality and friendship. The food

was plentiful and varied, with some moose and caribou occasionally

served. My young wife found the heart meat a bit revolting to her mind

– it tasted great till she she was told what it was! Then she asked to

use the toilet and was shown into a bedroom. When she protested that it

was a bathroom she needed, she was shown a bucket in the corner!

Bathrooms were luxuries few outport houses possessed then.

Old houses in a St John’s street

The capelin run was an

exciting annual event that brought most of us to one of the local

beaches to witness. Those anchovy-like fish swam inshore and spawned in

schools on the shore. They would swim on to the beach in threes – two

males and a female – and deposit their spawn and sperm on the pebbles or

gravel. They made an excellent dish when fried fresh. To me the

nearest fish in taste and shape to the capelin, are the slightly larger

flying fish which we used to catch and eat in the Pacific and Indian

oceans.

The open moorlands of

Newfoundland were briefly covered in berries late summertime. There were

different sorts, but to collect any you had to be quick as the season

was very short. I sometimes wondered if the Viking name of “Vinland”

for the island, was a reference, not to grapes as widely assumed, but to

the berries that abound for part of the year. I doubt if wild grapes

could have survived that far north in the past thousand years.

At the beginning of my

second year in the new world, I flew home to marry my Scots sweetheart.

On the way home I changed planes at Gander airport where I literally

bumped into Prime Minister Harold Wilson in the bookshop. He was on his

way to Washington to seek financial help for Britain’s ailing economy

from President Johnson. (He obtained the assistance, but it effectively

silenced him from voicing any further objections or concerns about the

Vietnam war). However, to happier things, - we set up home in a cosy

new wooden bungalow at the edge of the woods behind the north-west side

of the city of St. John’s. It was typical of the Newfy people that they

gave us a second wedding reception on our arrival. Our first year of

wedded bliss was unalloyed by the sub-zero temperatures and severe

snowstorms that continued through the long winter.

Newfoundland Scenes

Portuguse schooner

St. John’s has a fine large natural harbour protected by high

rocky land on either side of the narrow entrance. The promontory on the

north side of the entrance is known as “Signal Hill” as it was from

there in December 1901 that Guglielmo Marconi received the first

trans-Atlantic radio signal, - the letter “S” transmitted repeatedly

from a station in Cornwall, and received by an aerial wire held aloft

with a kite. On the same side of the

harbour is the site of a former military defense battery. I have

stood on Signal Hill when the harbour was frozen over, and the ice

extended 3 miles seaward. A trawler was caught in the ice half a mile

away, and its crew had been able to walk ashore.

Above : Outside our first home in St.

John’s, Newfoundland

We visited Signal Hill

and the Battery often, and my young wife celebrated her 21st

birthday in the battery restaurant over-looking the harbour. We were to

return for a reunion dinner 21 years later, and were joined by the same

lovely Newfoundland couple who were with us on the first occasion.

Bertha hailed from Red Bay in Labrador, and she often related how life

was growing up on that remote coast. Bob had worked for the Hudson Bay

trading company as a young man, and had equally interesting tales to

tell.

A Mrs Betty Adams from

Edinburgh, who used to be a customer of my wife’s parents fruit and

vegetable shop in Morningside, became a trusted friend. Her

Newfoundland husband, Charles, was a fine member of a notable local

family who were active in fuel supplies and distribution, and in

politics. Bill Adams, a lawyer, was then running for Mayor of St.

John’s, a position he won and held with distinction. They were typical

of the fine town people of the Province. Our departmental secretary at

the College, Margaret Hiscock, became a close friend. She went on to

become secretary to a subsequent Premier of Newfoundland, Brien Peckford.

I had met Joey Smallwood during his tenure, and knew his successor,

Frank Moores when he was managing a fish plant in Carbonear. When

Newfoundland joined the Canadian Federation in 1949, it was (in the

words of a Newfoundlander I knew), “a poverty-stricken hole” with a

population of 300,000, and 52 millionaires who had mostly made their

money from the fishing industry, amplifying it later by obtaining the

franchise or dealership for heavy equipment and other manufactured

goods.

I visited mining towns

in central Newfoundland, and stayed with families who lived in

“tar-paper shacks”, - small houses made of tar-coated, insulated

cardboard sheets nailed over a simple wooden frame. Those mining

settlements were rather depressing. The company controlled everything,

and if a resident fell into disfavour, his or her future there was bleak

indeed. On the west coast there were some poor French-speaking

communities, some of whose unemployed men sometimes attended vocational

courses at the college. We also had a few students of Eskimo origin

attend from Labrador.

I recall a meeting with

small scale fishers near Corner Brook where they were berated by Fishery

Officials for their lack of enterprise. They sat there meekly, taking

it it all in silence, and leaving it to their parish priest to speak for

them. Towards the end of the meeting, being young and a bit too

outspoken, I expressed strong disagreement with the attitude of the

officials who seemed to think the poor fishers should lift themselves up

by their bootstraps. I urged the speakers to look at things from the

situation of the powerless and vulnerable community, and opined that a

much more effective and realistic development programme was needed. The

statement brought an immediate response from the silent fishers who

suddenly broke into into a spontaneous burst of loud applause. It was

then the turn of the officials to maintain a stony silence. Many years

later I was invited by Simon Fraser University to participate in a

community workshop for the residents of the Change Islands, - a small

isolated community on that tiny rocky location situated between the

northern tip of Newfoundland and the coast of Labrador.

Other parts of Canada

we visited, apart from all of the eastern maritime states, were Ontario

(of course, - where most Scots immigrants gravitated to), Quebec, and

British Columbia. My older brother, a civil engineer, and his family

had settled in Toronto, after working some years in Nova Scotia, on the

construction of the Cabot Trail and the Trans-Canada Highway. Billy was

a fine amateur golfer, and won several trophies in competitions held in

Nova Scotia and Ontario. From Toronto we drove to Ottawa to visit

friends we knew in Rome, and to attend an interesting session of the

Canadian Parliament. In Vancouver, I had lovely relatives in a

half-sister of my mother, and her two lovely daughters. Aunt Nell, at

over 80, still stood ramrod straight, and had a sharp intellect and an

enquiring mind. She had been a real pioneer in the Yukon territory

during the 1920’s and 1930’s.

Whenever I think of the

Yukon territory and the klondyke days, my mind goes back to a second

generation Scot, a writer, who worked for the Canadian Bank of Commerce

in some of the wild Yukon territory outposts like Whitehorse and

Dawson. He painted the characters and life of the frontier fortune

hunters, in marvelous verse. I refer to Robert Service. Readers will

know who I mean the minute I quote the titles of some of his works :

the Shooting of Dan McGrew; the Creation of Sam McGee; the Law

of the Yukon; the ballad of One-eyed Mike; Once I found his book

“Songs of a Sourdough”, and the various collections of his verse, I

could not resist putting them to memory, and reciting them to friends on

the odd occasion when a social evening was getting dull.

Picture of my late brother Billy with

several of the golf trophies he won in Canada.

The Yukon and Rocky

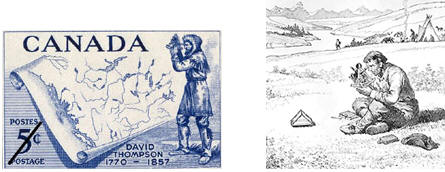

Mountain range also bring to mind the work of an English-born explorer

of that region, - a namesake of mine. Along with the Lewis born Scot,

Alexander MacKenzie, David Thompson ranks as one of the premier

explorers and surveyors of North America. He was born in England in

1770 of a Welsh father who died when David was an infant. At the

amazingly early age of 14, he sailed to Canada as an apprentice to the

Hudson Bay Company at their Churchill station. He was to develop great

skills as a surveyor, and was to take considerable interest in the

native Indian populations. Dissatisfied with his work as a fur trader,

he joined the North West Company on Lake Superior in 1797. For the next

20 years and more, Thompson was to explore and map most of North West

America, including the border between the USA and Canada. Simon Fraser

was to name the Thompson river after him. (see box below).

Above : Robert Service the great poet of

the Yukon and the Canadian west

Above : map of David Thompson’s

explorations

postage stamp of

Thompson Thompson surveying

|

A remarkable explorer and geographer

A west Canadian mountain

peak and river, are rightly named after a remarkable explorer

who surveyed and mapped these immense areas when working for fur

trading companies in north and north-west America. David

Thompson had arrived in Canada as a young teenager. He quickly

took a deep interest in the land and its people. At the age of

eighteen he was tutored by Philip Turnor, an astronomer and

surveyor employed by the Hudson Bay Company. That appears to

have been the extent of Thompson’s formal scientific education,

and in many ways he resembles the great 18th century navigator,

James Cook, who was also largely self-taught.

His skill and travels are

all the more remarkable when one considers that an early

accident left him blind in one eye and limping from a leg

fracture. He persuaded the trading company to furnish him with

a compass, watches, thermometers, sextant, an artificial

horizon, and nautical almanacs. He was to explore and chart

much of northern Manitoba and Saskatchewan, the Missouri river,

and the great lakes. His greatest journey was a pioneering trek

across the Rocky Mountains and down the Columbia river to the

Pacific coast. No photograph of him exists, but his

contemporaries recalled his character. He never used alcoholic

liquor. He was marked by stubborn honesty strengthened

by steadfast and earnest devotion to simple religious

principles.

In 1812 Thompson was

appointed to the commission that surveyed the border between

Canada and the United States. His work was accepted and remains

the authoritative basis of the border to this day. The merged

companies of Hudson Bay and Northwest treated his work with

indifference, and had his maps published without credit to their

cartographer. He died in obscurity, in Montreal in 1857, by all

accounts, blind and penniless. It was to be 50 years later

before a monument was erected over his grave, in tribute to the

splendid achievements of the man who traveled fifty-five

thousand miles on foot, horseback, sleigh and canoe, and who

mapped 1,900,000 square miles of north-west Canada, and much of

the USA north-west. |

Scots featured

prominently in Canada’s history. Alexander MacKenzie, mentioned above,

was a fur trapper with the Northwest Company (which later amalgamated

with the Hudson Bay Company). He gave his name to the Mackenzie river

which he explored for most of its 3,000 miles from lake Athabasca in

Alberta, up into the Arctic ocean. Then he crossed the Rockies to the

Pacific coast, accomplishing that feat ten years before the famed Lewis

and Clark expedition. These wilderness travels took place between 1789

and 1793. After the Northwest Company merged with the Hudson Bay

Company, it was governed by a redoubtable west highland Scot, George

Simpson, who among his several eccentric habits would take a piper with

him to play pibrochs as they sailed over remote rivers and lakes.

With the passing of the

British North America Act, Canada gained Independence from Britain in

1867. This measure was achieved in large part by John MacDonald who

emigrated at an early age with his parents and who worked and struggled

to acquire a Law degree in Ontario. This later led him into politics,

and leadership of the Liberal-Conservative Party through which he sought

to build bridges with the French settlers in Quebec and New Brunswick,

and gain their support for the independence arrangements. He went on to

become the united territory’s first Prime Minister.

Another remarkable Scot

was Sandy Fleming, the chief engineer behind the 3,700 mile Canadian

Pacific Railway which was completed in 1885. The railway track’s

mountainous terrain with its many rivers and gorges were as challenging

as any team of surveyors and engineers had ever faced. But Fleming went

on to tackle another problem in an even more significant way. In the

late 19th century, in most parts of the world, clocks were

set by sunrise and sunset, and there were few places outside of Britain

that used a standard time. Simpson, who needed a common time for all

railway clocks across Canada, solved the difficulty by dividing the

world into 20 time zones of 15 degrees longitude each, and had the

scheme accepted at an international conference in Washington in 1882.

Global time was synchronized and commenced the following year.

my father introducing pair seining to the

Canadian Maritimes

In addition to the

notable Canadians of Scots origin, there were of course, thousands of

emigrants and settlers from that land. Some arrived out of the distress

of the potato famine, and from the cruel Highland Clearances, but many

others arrived simply seeking opportunity in the new land. Orcadians

were prominent in the Hudson bay Company which some joked they joined to

seek a warmer change from the cold winds of Orkney. Ontario, even more

than Nova Scotia, was replete with Scots or folk of Scots descent.

Vancouver also had a large Scots community till they were swamped by

immigrants from across the Pacific. My Aunt Nell was one of those who

left Morayshire to work in the wild frontier of the Yukon trail, later

settling in Vancouver with her family.

Two very contrasting

Scots-Canadian figures of the 20th century, that have long

fascinated me, were Baron Lord Tweedsmuir, better known as the author

John Buchan, and Malcolm MacDonald, son of Ramsay MacDonald. John

Buchan was Governor General of Canada from 1935 to 1940, while Macdonald

was British High Commissioner for the country from 1941 to 1946. Though

both men were well-travelled, held several public offices, and wrote a

number of books, they were very different in character and attitude.

One, the son of a Prime Minister was remarkable for his lack of

self-importance. The other, a ‘son of the manse’, exhibited some traits

of the aristocratic class of his time

Above Left: Malcolm Macdonald British High Commissioner for Canada.

Right : John Buchan (Lord Tweedsmuir) Governor General of Canada.

Malcolm MacDonald who had been a Minister in pre-war and wartime British

Governments also held a number of Governship positions in Africa, Asia

and the Far East, but would not accept any of the titles that were

offered to him. The Foreign and Colonial offices tried to persuade him

to accept a knighthood or lordship on the grounds that huge important

countries like India and Canada would not be impressed by a plain

“Mr.”. Well, plain Mr. MacDonald was not impressed with the argument!

By all accounts he performed well in each of the positions he held, and

went on to undertake substantial preparatory work for the process of de-colonisation

that was beginning after the war. The books he wrote mostly concern his

experiences in the countries he helped to govern in south Asia and

Africa

John Buchan was 26

years older than MacDonald. He saw service in the first world war, and

like many writers of espionage tales, was for periods involved in

intelligence work. He was a “son of the manse” as we say in Scotland of

those whose fathers were Church of Scotland ministers. Had he not held

high public office, Buchan would still have been very famous for his

novels. But being Governor General of Canada added to his reputation,

and at one time his picture appeared on the front cover of Time

magazine.

But for me, it is the

novels he wrote that reveal the more fascinating side to the man. They

are strange books in some ways, - perhaps a bit like the novels of

Jeffrey Archer. They are replete with the most unbelievable

coincidences, - so bizarre and unlikely, that you almost shake your head

in disbelief and laughter at them. Yet, - there is something about his

simple tales of political intrigue and adventure, - that once you start

reading, you cannot stop till you reach the final page. At least that

is how it is for me. Yet the stories, like The 39 Steps,

Greenmantle, Island of Sheep, Mr Standfast, and Prester John,

also say something about Lord Tweedsmuir’s personal attitudes. He

often wrote in the first person, and you get glimpses of an attitude

towards foreign countries, union workers, social classes, and the status

quo, that is decidedly and self-righteously bourgeois. So one could not

conceive a greater contrast with Mr Malcolm MacDonald, the son of

Britain’s first Labour Prime Minister! Yet

I was reliably informed by a grand-daughter of Ramsay MacDonald’s, and

niece of Malcolm, that the two got on extremely well, with Lord

Tweedsmuir showing Malcolm much friendship and respect.

Canada even had a mountain named after Ramsay MacDonald’s eldest

daughter in 1956. The magnificent Mount Ishbel lies in the part of the

Rocky Mountain range within Banff National Park, in Alberta. The view of

Mount Ishbel below is as it appears from the Bow Valley Parkway.

Canada today still

remains a young man’s (or young woman’s) country. It is fresh, clean,

friendly, and has enormous wide-open spaces. During my time there you

could drive along the Trans Canada highway for hours, and see very few

other vehicles. The vast forests and prairies, the magnificent Rocky

Mountains, the rugged east coast and the scenic Pacific coast, - all

combine to make Canada one of the most beautiful and environmentally

pleasant countries in the world. If Canada has a drawback, it is the

severely cold winter residents must endure. The low temperatures are

experienced mainly in central, mid-west and maritimes Canada, but to a

lesser degree along the Pacific coast. I have known several British

immigrants who loved their new adopted land, but who had increasing

difficulty in enduring the long cold winters as they grew older.

The ethnic mix in

Canada has changed enormously in the past few decades, mainly due to

enormous immigration into British Columbia from the Far East and south

Asia. Rather like Honolulu, but to a greater degree, Vancouver has

become an ethnically ‘Asian city’. In the past 300 years, English

people dominated in most provinces, with French in Quebec and New

Brunswick, and patches of Scots in Nova Scotia, Ontario and British

Columbia. Italian and German immigrants have gravitated to Ontario, and

there are smaller groups of Caribbean people in the east of the country.

Canada suffers a bit as

the ‘little brother’ to the big USA, and is regularly treated so by

American administrations. They want its fresh water, its oil and gas,

and its markets for the products of America’s huge industries. But the

relationship often appears to be much too one-sided for most Canadians,

and in this they are probably correct. As I have opined elsewhere, the

United States believes in free trade only when it suits her. When the

trade is seen as damaging to U.S. domestic interests they do not

hesitate to twist the rules. Political pressures are also put on Canada

to support US foreign policies, but for the most part the country has

been able to resist them.

What better to end my

scattered thoughts and recollections on the magnificent land of Canada,

than with a few verses from the pen of Robert Service:

I am the land that listens, I am the land

that broods;

Steeped in eternal beauty, crystalline waters

and woods.

Long have I waited lonely, shunned as a thing

accursed,

Monstrous, moody, pathetic, the last of the

lands and the first;

Visioning camp-fires at twilight, sad with a

longing forlorn,

Feeling my womb o’er-pregnant with the seed of

cities unborn.

Wild and wide are my borders, stern as death is my sway,

And I wait for the men who will win me - -

and I will not be won in a day.

And I will not be won by weaklings, subtle,

suave and mild,

But by men with the hearts of Vikings,

and the simple faith of a child;

Dreaming of men who will bless me, of women esteeming me good,

Of children born in my borders, of radiant

motherhood,

Of cities leaping to stature, of fame like a

flag unfurled,

As I pour the tide of my riches in the eager lap

of the world.

Robert Service

The Law of the Yukon |