|

“Again Livingstone

set out on his weary way, untrodden by white man's foot before, to

pass through

unknown

tribes,

whose savage temper might give him his quietus at any turn of the road.

There were various routes

to the sea

open to him. He chose the route along the

Zambesi--though

the most difficult, and through hostile tribes--because it seemed the

most likely to answer his desire to find a commercial highway to the

coast. Not far to the east of Linyanti, he beheld for the first time

those wonderful falls of which he had only heard before, (the local

Bantu name was Mosi oa Tunya, meaning ‘the smoke that thunders’).*

Livingstone gave them an

English name,

-- the first he had ever given in all his African journeys, -- the

Victoria Falls.

This discovery was the one that took most hold on

the popular

imagination, for the Victoria Falls are like a second Niagara, but

grander and more astonishing; but except as illustrating his views of

the structure of

Africa,

and the distribution of its waters, it had not much influence, and led

to no very remarkable results. Right across the channel of the river was

a deep fissure only eighty feet wide, into which the whole volume of the

river, a thousand yards broad, tumbled to the depth of a hundred feet,

the fissure being continued in zigzag form for thirty miles, so that the

stream had to change its course from right to left and left to right,

and went through the hills boiling and roaring, sending up columns of

steam, formed by the compression of the water falling into its narrow

wedge-shaped receptacle.”

The Personal Life of

David Livingstone, William Garden Blaikie

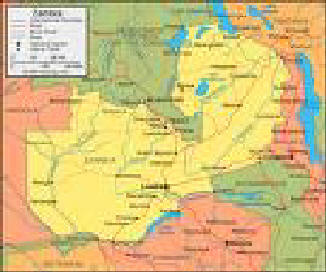

I flew to Northern

Rhodesia in 1962 on a Boeing 707 jet that stopped at Rome, Benghazi

Libya, Brazzaville Congo, and Salisbury Southern Rhodesia. Before

departing London, I had tasted my first hamburger, and at Rome’s

Leonardo

da Vinci airport

I drank my first coca cola. (I haven’t cared much for either since). I

was sat beside a young man of my age who was going out to learn how to

manage a tobacco farm. I have often wondered since what became of him.

During the stop-over in Salisbury, a Scottish schools inspector,

Campbell Duthie, nephew of the MP referred to earlier, kindly showed me

around the city and gave a brief overview of the country and its

history. His wife had been a friend of Miss Boyne, the school-teacher I

referred to in the account of my primary school memories. Africa was

like that. Scots especially kept running into acquaintances or friends

of acquaintances. I was surprised that the Duthie’s had a log fire

burning in their large living room. In the UK we sometimes forget that

many parts of Africa can be cold or chilly at times. I was later to

encounter snow and sub-zero temperatures in Johannesburg and Windhoek.

At Lusaka airport I was

met by two fine men who worked then in the Northern Rhodesian Game and

Fisheries Department. Jim Soulsby, Fishery Officer South, was an

excellent technical officer, and was later head of a London company,

Fisheries Development Ltd. Colin Tait, a young South African of

Scottish parentage, was a Ranger on Lake Kariba. Colin was marvelous

company to have in the long dark nights in the bush, with his love of

jokes, and his fund of songs and stories. After a couple of days at the

Fisheries Offices in Chilanga, I headed down the valley with Colin.

Weather on the plateau was sunny and pleasant. The temperature rose and

the atmosphere got dustier as we drove down the 2,000 foot escarpment to

the Zambesi valley.

At Sinazongwe, now a

research station, the fishery training centre was nearing completion.

Dick Heath, a master boat-builder from Sussex was then in charge. The

centre had sheds for assembling nets, building boats and repairing

motors. There was a kitchen, a dormitory, and a few dozen staff houses.

A South African builder, Tommy Thompson had a team of semi-skilled

workers putting up the buildings. Concrete blocks were made on the spot,

and the corrugated tin roofs were supported by light pre-fabricated

steel frames.

The expatriate officers

had larger houses of the same construction, with either 2 or 3 bedrooms

and a screened verandah. They were originally built to accommodate the

operators of bush-clearing bulldozers who were hired to clear fishing

pitches in level areas covered by mopani trees, before the lake water

rose. One of the drivers was run over by his own bulldozer that jumped

unexpectedly into reverse. He was buried on the spot, and his grave

marked by a black wooden cross on a lump of concrete. I came upon it

one day in the bush behind my house when exploring the area, and

thought, “what a place to die; and what a lonely grave to have”.

A 45 gallon oil drum

set long-ways on bricks above an outside fire box, served as a hot water

tank. It was filled by a hose, and had a pipe leading from its base

into the bathroom nearby. The houses also had air-conditioners of

sorts. These were metal boxes stuffed with straw, behind which a fan

blew air through the straw into the room. The same fan drove a small

pump that drew water from a tray below the straw, and let it trickle

back down from above. The resulting effect was not as poor as might

seem, although one got hit by drops of water, as well as experiencing a

slight fall in the room temperature. Water came from a station tank fed

by a borehole pump. This often broke down, especially towards the end

of the dry season. The station generator was stopped at 10pm each

evening, so one had electricity and light, only till then. On the

numerous evenings when the engine operator Cosam had a social

engagement, the generator and the electricity ceased functioning

earlier.

Kariba Dam

Kariba-generated

electricity never reached remote outposts like Sinazongwe. It was

conveyed by power cables, south to Salisbury (now Harare), and north to

Lusaka and the copperbelt towns of Kitwe, Ndola and Mufulira. The dam

had been proposed partly as a Federation project, - an enormous

investment in energy generation that would be seen as both a benefit and

a symbol of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. As things

transpired, the much-vaunted central African federation disintegrated

within three years of the dam’s completion. Apart from the loss of

their ancestral homes from the formation of the lake, and the subsequent

development of a fishery in the lake waters, the dam had little other

effect on the valley Tonga peoples.

The Africans of the

Gwembe valley were mostly Ba-Tonga people. Father north, north-east and

north-west were Bemba, Lozi, Nyanja, Kaonde, Lunda and Luvale tribes.

The Batonga were then as a poor and as primitive a people as could be

found in the country. The women wore beads on their heads, arms and

tummies, and sometimes had sticks inserted through their ears and noses

for decoration. They also had their front teeth removed, or the older

generation did, for reasons which were obscure. The men invariably

carried an axe made of a club-like piece of mopani wood, with an iron

axe-head, pointed at the back, inserted through the stouter end. They

were a friendly, simple people, who enjoyed a joke, and who never failed

to greet passers by, which was done in a very respectful and

time-consuming manner.

So many times when driving through the bush, I was saluted by a Batonga gentleman

whose clothes were in rags, but who looked me

in the eye and proudly

gave his greeting, and expected a similar respectful salutation in

return. “Mwapona” (you are seen, or hullo), “mwapona Mwami”

(chief or sir), “mwapona kabotu” (it is good you are seen, -

or are you well), … and so on. Those poor people were all that I had

heard “bush” Africans could be. They were polite, sincere and honest.

Batonga village

In three years in that

valley, no-one ever showed me the slightest hostility, and no-one stole

a thing from me (apart from the little bit of sugar, etc, that my cook

would take, but that was one of the perks of his job).

In his book, “The

Shadow of the Dam”, David Howarth describes the Gwembe people as

seen through the eyes of District Commissioners and District Officers of

the late 1950’s. “With the Tonga, nobody needed to be tough. Each

District Commissioner who took over the Gwembe Valley grew fond of the

Tonga, because they were charmingly cheerful and happy-go-lucky when

times were good, and courageous when times were bad, and because they

were courteous, kind and friendly but never servile; in short, because

on the whole they were lovable people.”

Bush clearing : large areas of Mopani

trees were cleared to make room for fishing grounds where nets could be

set without fear of entanglement. However that still left substantial

areas of flooded forest where fish could breed and grow protected from

both fishing nets and predator fish.

Naturally, I could

hardly wait to get my first sight of the lake, the boats and the fish.

There was a natural harbour and a concrete sloping pier 3 miles up the

lakeside from our station. An ice plant had been erected there by a

South African firm, and was operated by a cheerful Johnny Young. Fish

traders came down from the copperbelt towns in a motley assortment of

trucks and half-trucks. They packed the fish they purchased (at 4 old

pence per pound), in the ice, with straw for insulation. The fishing

boats themselves landed at a number of places along the lake side, and

the traders would drive to one of these spots after purchasing his ice.

Invariably at the landing site there would be weighing-scales operated

by a fishguard in a boy-scout like uniform, with two other fishguards

noting the amounts and the species in pre-printed log books, in

compliance with the Colonial fixation for recording everything.

There were four boat

types in operation, - dug-out canoes as used before on the river Zambesi,

flat bottomed planked boats of local construction, and clinker-built

‘banana’ boats built at our centre on the lines of the Irish curragh.

The fourth type were metal boats built by a fabrication yard in Lusaka

to specifications determined by an ex-naval District Officer. They

looked like matchboxes with a pointed end! The dug-out canoes were

suitable for use on calm days only. The flat-bottomed canoe was also

more suited to river conditions. The curragh-based ‘banana’- boat canoe

was excellent in all respects, - it was seaworthy, manoeuvrable, had

good capacity, and could be either paddled with ease, or power-driven.

Of the ‘metal-box’ boat, - the less said the better. It was so unsafe,

it had buoyancy tanks welded in fore and aft, and these left little

room for men, nets or fish. Also the bottoms rusted through within a

year, which annoyed the owners who had purchased them on a 3-year loan.

But such monstrosities were often inflicted on native populations by

Colonial rulers. I used to think the rondarvel ‘tin’ huts were a

similar disgrace. They had been designed as a fast and easy answer to

native housing, and could be assembled quickly from galvanized metal

sheets. In shape they resembled native pole-and-mud huts, but that was

the only concession to traditional design. They made excellent solar

ovens, but as human dwellings, they were an abomination.

Myself surveying our little fleet on the

lake

The lake itself was filling up and nearing its highest point

when I arrived. I believe that point was attained during the November –

February rainy season which was just 3 months away. Most days the water

was fairly calm, but a regular breeze came up the valley from the Kariba

gorge to the Victoria falls, and at times it made the exposed parts of

the lake quite rough, with short choppy seas that would have presented

no problem to marine vessels, but which could make conditions

uncomfortable for the small open boats in use on Kariba. At times the

breeze could create small whirlwinds and waterspouts.

With a copperbelt trader, examining dry

fish

The range of fish

species was intriguing. I had no idea tropical freshwater fish came in

so many different shapes and sizes. There were mud-sucking labeos,

slimy catfish, razor-toothed tiger fish, huge tilapia bream, spiny

synodontus and long-nosed myropsis, as well as numerous smaller

species. Later, the Lake Tanganyika sardine, “kapenta” or

”ndaaga” (Limnothrissa) were introduced to Kariba, and quickly

filled an environmental niche in the deeper parts of the lake, and

became the basis of a large light-attraction fishery. But that was just

after my time there, though the matter was then under consideration.

Above :

Handing over a new boat to local

fisherman Gray Madyenkuku and his wife

Kapenta fish, limnothrissa, the

small anchovy-like species introduced from Lake Tanganyika to the

benefit of Kariba fishers. On the right, tiger fish, hydrocyon

vitattus, the fierce game fish in lake Kariba

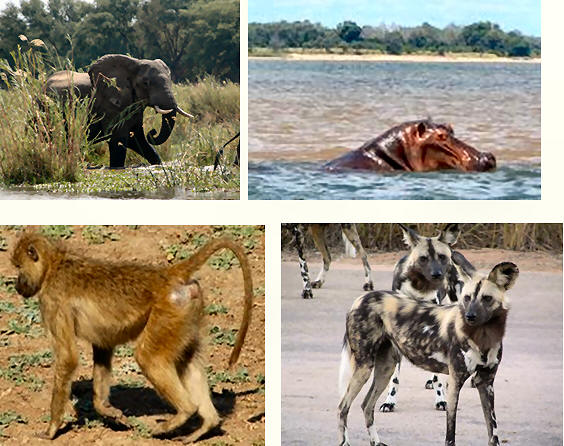

Of wild-life there was plenty then, though my first

impression of the bush was that it was devoid of life apart from ants

and termites, lizards, flies and hornets. The rising lake had moved

animals up from the valley, and for a while the shore was replete with

animals, mainly snakes, but also

monitor

lizards, chameleons, baboons, warthogs, small antelope, kudu

and elephant. There had been an “operation Noah” mounted to rescue some

of the animals from the rising waters, and a film was made of those

activities. In my time there, in addition to those mentioned above, I

encountered hyenas, wild dogs, hippopotamus, crocodile, aardvark

ant-eaters, bush babies, civet cats and genet cats, and one

leopard. There were hardly any lion in the valley.

It was the snakes I

disliked. My first year there, I think I saw one every day. There were

large pythons, boemslangs, sand snakes, spitting cobras and puff-adders,

long mambas, and smaller tree snakes and grass snakes. One of my cats

was spat on in the eyes by a cobra, but survived, and my dog died from

snake bite after I had left. Today I see naturalists on television

handling such snakes with seeming ease. I never had any inclination to

get close to them. Below are examples of the wild life I saw regularly

in the valley: elephant, hippo, wild dog, kuu, baboon, monitor lizards,

and a mamba snake – I saw a great of variety of snakes around the lake,

encountering them every week if not every day.

Bottom – a large monitor lizard, common

in the Zambesi valley and sometimes mistaken for crocodiles.

Below :

Elephants and hippos in Lake Kariba and Babboon and wild dogs were

abundant in the valley

Mosquitoes came out in

force every night, and it was next to impossible to avoid getting bitten

regularly. I took my daily chloroquin pill, and never succumbed to

malaria or to denghi fever. Apart from mosquitoes, there were tiny lake

flies that hatched out and appeared in hordes for a few days. They were

so small they went through the mosquito screens with ease, so it was

“lights out” on those nights. The infection my colleagues feared more

was bilharzia, or schistosomiosis, from a parasite that

moved from water snails to humans and animals, and could kill if not

treated. I escaped that infection also, but fell foul of amoeba, and

had at least one bout of amoebic dysentery. The single cell parasites

were to remain lodged in my system for 15 years by which time they had

developed abscesses in my liver. By 1977 – 78 I was weak and

debilitated but no doctor could diagnose the problem till I underwent a

liver scan in the Makati Medical Centre in Manila. When they detected

the abscesses, they cheerfully informed me I had about three months to

live if they were not eliminated from my system. A cocktail of drugs

was prescribed and within a few weeks they were gone. I was then very

thin, but 2 years after the cure I put on weight and have not been able

to lose it since.

My first bout of

amoebic dysentery occurred in a remote village in the upper Gwembe

valley where I and a colleague Peter Cocker, were both afflicted

suddenly one night after eating local food. We took turns to use the

temporary ‘PK’ (pikaniny kayak, or ‘little house’) down the path

from our camp. At the the first light of dawn a line of local women

came by heading towards the river with their water drums on their

heads. Poor Peter was unable to wait for me coming out of the bush

toilet, and he had squatted down by the side of the path. I could not

help laughing through my discomfort as I heard him exclaim to the

passing women, “I’m sorry ladies, - but I just can’t help it” !

A magnificent kudu antelope. They were

plentiful in the valley when I was there.

It

was not long before I had the opportunity to visit the magnificent

Victoria Falls near the town of Livingstone. Later I was to travel

north to the huge inland sea of Lake Tanganyika, and north-west to Mweru

and Bangwelu lakes. I sailed over lake Mweru with the local fishery

officer Dermott Beattie, who hailed from Northern Ireland, and visited

the Katanga part of the Congo. That was when Moise Tshombe was still in

charge, but when the UN troops were advancing to destroy the secession.

We visited a local Catholic mission, hospital and a fishery school where

the houses were painted like ships and named after French vessels like

the Lusitania. The students wore sailor uniforms and spoke both

Bemba and French. To honour us, they linked arms and sung “My bonnie

lies over the ocean”, swaying from side to side as they did. I

often wondered what became of them when the Congolese troops crushed the

Katanga secession shortly after our visit.

Africa then still had its share of adventurers and maverick

characters. The white settlers and whites born in Africa, have included

some rugged individuals who would perhaps have been more suited to

frontier life in America in the early 19th century. There

are still a few around today as could be seen in the bizarre attempt to

mount a coup in the tiny (but oil-rich) state of Equatorial Guinea.

When I came to Northern Rhodesia there was a man of such reputation

around, by the name of James Finlay Bisset. It was alleged that he and

a band of fellows had “invaded” Tanganyika during World War 2, to keep

it from the Germans. Around 1960 he was reputed to have punched a

visiting US Secretary of State for pronouncing an anti-colonial policy –

“Africa for the Africans”. Bisset arrived on lake Kariba in 1962 with a

fleet of small boats and some miles of nylon gill nets, claiming that as

a national of the country he had a right to fish there. The District

Commissioner John St. John Sugg, eventually got him to abandon the

venture, not that I suppose it bothered Finlay-Bisset. (A grand neice

of his wrote

to me after seeing Reflections on the internet, and

asked me further about her redoubtable relative.)

Victoria Falls

Admiring the statue of David Livingstone

beside the Falls, 1962. Above : David Livingstone, the Scots

missionary and explorer

|

David

Livingstone and the Gwembe Valley

The Scottish

missionary–explorer trekked around the south, east, and

centre-east of Africa for over thirty years in the middle of the

nineteenth century. His journeys extended from the regions of

the modern states of South Africa to Zambia, to Tanzania and

Uganda. I arrived in the Zambesi valley just over a hundred

years after he had visited the Kariba gorge, (in 1860, after

discovering and naming the Victoria Falls in 1855). When

Livingstone met Tonga tribesmen, he described them as “very

degraded”, and from his Victorian and Scots Calvinistic

background, was particularly disturbed by their near-nakedness.

Even their kindness and friendliness were strange to him. “They

always brought presents of maize and mazuka. Their mode of

salutation is quite singular. They throw themselves on their

backs on the ground, and, rolling from side to side, slap the

outside of their thighs as expressions of thankfulness and

welcome .. This … was to me very disagreeable.”

Despite his Victorian and

Scottish Presbyterian hang-ups, Livingstone came to love the

people, and sought to free from the raids of Arab slave

traders. He spent some time at the main village of Chief Mwemba,

50 miles to the south of the Falls. Jobo Michello, the

politician, a descendant of the Chief’s, told me a story from

that period that does not appear in any published records. When

the missionary came to leave the village and move on north, he

called the Chief and his headmen together. Livingstone held out

a cob of corn in one hand, and some bullets in the other, and

asked the Chief which he wanted for his people. Chief Mwemba

chose the cob of maize corn. Livingstone told him he had well

chosen, but informed him that other white men would follow in

years to come, and some of them would bring bullets. “When they

come, - give them this letter”, said Livingstone, handing him a

hand-written letter in an oilskin pouch.

Michello said that the

Chief and his family kept the letter for years, till it was

suggested that perhaps it contained some black magic, so then it

was buried in an anthill just outside the village. “My

grandmother knew where it was buried”, said Michello, “but, no

matter how often I pressed her, - she would never reveal the

location to me. I often wondered what was written in that

letter.” |

Travelling around the

country was a pleasant experience for a colonial employee. The

administration had its strict codes which were designed to maintain

standards and to ensure smooth operations. There were guest houses at

most locations, or if not, you stayed in the guest room of a local

officer. There was a strict protocol on behaviour. You had to dress for

dinner. You had to tip the domestic staff, and to write a letter of

thanks to the host and hostess. And when making the travel claim, there

was an obligatory amount to be sent to the hosts for the hospitality

provided. The PA or Provincial Administration kept a careful eye on the

public and social behaviour of the expatriate officers. Any officer

posted to a remote field station who was suspected of lowered standards

or “going bush” and adopting a rough lifestyle, was quickly recalled to

the central office or station for a dose of exposure to civilized

conduct.

The Kariba valley was

not beautiful, though the lake could be pleasant when the weather was

clear and calm. The high plateau was much more impressive. What

sunsets and sunrises ! There is nothing to compare with the freshness

of an early morning on the east-central African plateau, or the evening

chorus of gnats and grasshoppers as a deep red sun sinks over the

horizon. The month of October was extremely hot and dusty in the

Zambesi valley. It was a bit like India before the monsoon, only less

humid. The fine dust hung in the air and penetrated one’s clothes, eyes,

nostrils and lungs, often carrying an assortment of infections. Then the

rains came in November, and for the next three months or longer, there

was one heavy shower after another. The bush seemed to blossom and

flower and become verdant overnight. Catfish emerged miraculously from

almost dried-up muddy holes, and made their way across land to the

rivers and streams. There were no bridges in the local rivers which

were dry for half the year, only concrete drive-throughs. During the

heavy rains the rivers became raging torrents, and driving through the

fast flowing water could be exciting.

A water engineer from

Bo’ness in Scotland, John Brooks, was driving a truck up the valley to

pay his large team of labourers. With him in the cab was John

Arnold-Edwards, newly arrived assistant to the District Officer. They

came to a swollen river. “Ach”, said John Brooks in his broad

Scots accent, “I’m afraid it is just too deep to cross”. “Not really

John”, said Arnold-Edwards, “Let’s have a go”. Against his

better judgement the older man drove on. The water caught the truck

half-way across, lifted it up, and swept it down-stream and into the

bank. The money-box was washed out of the lorry, and the last they saw

of it’s contents was hundreds of pound notes and ten shilling notes,

floating down the stream. Some astonished fisherman got an unexpected

windfall that day!

John’s younger brother

Joe McGregor Brooks, was a game and tsetse control officer based near

our centre. He was married to a Thai wife, Sena, and they had two young

sons. Joe was a colourful character who had a little kingdom of his own

there. He was one of the few Europeans I met who was fluent in the

Chitonga language. His station was well equipped and he had both fruit

and flowers in the garden. He even had a work-boat motor yacht for

visiting places inaccessible by road. There is a book about Joe’s early

life and work in Northern Rhodesia, “Elephant Valley”, written by

Elizabeth Balneaves, which I was able to obtain before leaving Scotland.

(Balneaves, from Shetland, lived into her nineties and died in 2006, in

Elgin near my home). When my father saw the pictures of Joe, living a

rough frontier life, and standing over elephants he had shot, his hairy

chest exposed, he said with his typical dry tongue-in-cheek Scots humour,

“David, I think that Joe Brooks would be a member of the exclusive

brethren”. Surprisingly, when I later came to know him, I

discovered that Joe had indeed been brought up in that strict sectarian

group!

Joe McGregor Brooks with a rogue bull

elephant he had just shot.

Talking of religion,

the staff at our centre represented a number of denominations. There

were Methodists, Anglicans, Catholics, Church of Christ and Jehovah

Witness members. Methodist missions predominated in the valley, and an

English Methodist missionary was stationed nearby. A lovely elderly

Irish Jesuit priest came down about once a month to say mass with the

Catholic members of the staff. He was a typical Jesuit, - serious,

well-read, and observant. I provided lunch for him on his monthly

visits, and enjoyed our conversations on the country, on its people, on

the politics, and on theology.

The colonial government

had a series of local district stations or outposts throughout the

country. These “Boma’s” housed the office of the District Officer and

his assistant if he had one. Their staff would include a number of

local policemen or boma guards who wore fez type hats. Colonial law was

concerned chiefly with serious criminal or political offences and left

all small issues to be dealt with by local chiefs under native law. The

old chiefs received a small stipend for their services. They dealt with

cases of theft, bride abduction or non-payment of lobola or

“bride-price”, and other lesser crimes like common assault. The chiefs

performed largely like wise magistrates. They needed to possess good

local understanding and wisdom to determine cases as Africans take

forever and relate all kinds of extraneous information before getting to

the point of their case. At times the chiefs displayed a wry sense of

humour. Tommy Thompson’s cook “Cement”, was up before our chief one day

on a charge of non-repayment of a borrowed sum of ten pounds. Chief

Sinazongwe found him guilty and fined him fifteen pounds. Cement started

to shout with anger, and protested at length that this was most unjust

as he had borrowed only ten pounds. He demanded that the fine be

changed. “All right, all right”, said the chief after the accused

had been quieted down, “I will change the sentence”. Turning to

the court clerk he said, “Fine him, - twenty pounds” !

During my first year in

the country, we were joined by two fine young officers who were to

become lifelong friends. Brian Mutton was a marine mechanic who did an

excellent job training fishermen to operate outboard motors, and

organizing their maintenance and repair. Sandy MacDonald was an

assistant district officer who had been a navigating officer during

brief naval service. Brian had also served in a branch of the navy, on

Fleet Air Arm patrol vessels. During his period in Zambia, Sandy built

a lovely 23 foot yacht based on a design of one that sailed across the

Atlantic. Brian was a skilled photographer and a fan of jazz music.

Both men went on to work in marine development projects in other parts

of the world. Brian has now retired in Queensland, Australia, and Sandy

runs a farm estate and boatyard on the most westerly point of the

Scottish mainland.

Two good friends and

colleagues of Zambesi days: Brian Mutton and Sandy MacDonald.

Zambia was then

preparing for self-government and independence. The Federation of

Rhodesia and Nyasaland was still in place when I arrived in Africa, but

it was doomed to disappear as each of the countries sought an

independent future. Cold war politicians saw the Federation as a

bulwark against communism, but as it had no grass roots support, that

could never have been effective in the long term. So, Nyasaland became

Malawi, Northern Rhodesia became Zambia, and Southern Rhodesia

eventually got recognition as the independent state of Zimbabwe. But

more of it later.

I was co-opted by the

Provincial Administration to assist with voter registration in the

Gwembe valley, and was sent to a poor remote village a sixty mile

journey from our station on very rough roads. Over a one-week period I

registered 1500 voters. That may not seem like much, but this was the

first time there was universal suffrage for all persons over 21 years of

age. Nobody in the village possessed a birth certificate, and few could

recall with accuracy the date of their birth. Only two dozen persons

could sign their names, all others simply made a thumb mark on the

papers. Some candidates looked far too young to me, and I would discuss

their ages through an interpreter, with the local chief. One young lady

I was reluctant to register, went outside and brought in her three

children. I gave in. “All right, my dear, - you may not be 21, but

you have earned the right to a vote”! One crazy fellow

arrived brandishing a spear, and performing a war dance in front of my

hut. As diplomatically as possible, I told him through the interpreter

that as he was insane, he could not be permitted a vote. He glared at

me for a minute, then threw his head back and laughed raucously, falling

down to the ground and shouting that he did not care if he did not get

the vote, since the District Commissioner had declared him exempt from

the annual native tax, because of his insanity. Then he grabbed his

spear and ran off up the hill and out of sight shouting all the way, “no

tax ! no tax ! no tax ! ”.

A strange episode of

bloodshed occurred in 1964 when Kenneth Kaunda’s party hacks tried to

pressure members of a sect to register and vote for the UNIP party.

This was contrary to the beliefs and practices of the group which

eventually turned violent. The sect was an off-shoot from a Church of

Scotland mission, and became known as the Lumpa church. It was led by a

prophetess, Alice Lenshina, who convinced her followers that bullets

would not hurt them if they had faith and shouted the rallying cry, -

“Jericho!”. In the end, scores of Lumpa church followers would die,

and Alice herself was imprisoned. Negotiations to avoid bloodshed were

led by District Commissioner John Hannah who I knew well as he

previously had a monitoring role over our Gwembe valley project.

There were two main

political parties which as in most of Africa, were based largely on

tribal support. UNIP, the United National Independence party was led by

Kenneth Kaunda and his more leftist and radical deputy, Simon Kapepwe

who was later to form a party of his own. UNIP was supported mainly by

the northern Bemba tribe. The ANC or African National Congress was led

by Harry Nkumbula whose support lay mostly with the southern Batonga

tribe. Kaunda had been in the ANC before, but broke with Nkumbula to

form his own party. Harry Nkumbula’s deputy was Jobo Michello who was

also to leave Nkumbula to form a third party, the PDP, People’s

Democratic Party. Nkumbula had been a good leader in his day, but like

rather many African politicians, in his later years there was a loss of

integrity and control as he over-indulged in alcohol and womanizing.

The British Colonial

government was making (in my view) an honest attempt to prepare the way

for handing over the reigns of power. This varied from provision of

training, and promotion of indigenous civil servants, to gradual

integration of formerly segregated establishments like government guest

houses. They were actually segregated by rank. You had to be of a

certain status to stay in the upper class government accommodation. But

for all practical purposes, that was also racial segregation. The

transition, when it came, must have been as peaceful as any in the

continent. We went from colonial rule to self government to full

independence, within the three years I was in the country, with hardly a

hiccup in how things were run. Few civil servants were dismissed, and

many Brits continued to work in the country for many years. Admittedly

some were appalled to be working under a ‘black’ government, and

magnified each little failure or immature word of the new

administration. Over in Southern Rhodesia, Roy Welensky, bereft of his

Central African Federation, blustered and bellowed, and threatened to

seek power again till Ian Smith became Prime Minister, and went on the

declare independence unilaterally. That was in the year after I left

Zambia.

Four parties contested

the self-government elections in Northern Rhodesia, - UNIP, ANC, PDP and

NPP the National Progress Party (which contested the ten seats reserved

for Europeans). PDP, the People’s Democratic Party, was formed by Jobo

Michello, the former ANC deputy. It surprised most pundits by coming a

close second to UNIP in several constituencies. After the

self-government vote, an interim government was formed, led by Kenneth

Kaunda as Prime Minister. Michello was consigned to the political

wilderness, and was sent down the Gwembe Valley to assist me in running

a revolving loans scheme for the Kariba fishermen, that had been set up

through a donation by the City of Nottingham through the Freedom From

Hunger Campaign. I visited the dynamic fund-raiser twice in

Nottingham. Mrs Charlotte Loewenthal was an intelligent highly

motivated lady of Jewish origin. Her husband, a medical doctor, was a

keen student of global politics, and a believer in an eventual world

government. Sadly, Mrs Loewenthal was killed in a car accident two

years after I left Zambia, and a few months before she was to visit

Zambia at the invitation of the Government.

The first day Michello

arrived at the station, I had not long got him accommodated in the house

formerly occupied by the boat-builder who had been moved to Chilanga

near Lusaka. I was then visited by the local leader of the ANC who

asked me what Michello was doing at our station, and how long he would

be staying. It was only then I realized that my new colleague was

Michello the politician. My staff regarded him with some awe.

Later, over occasional

dinners in my house, Jobo reminisced on his life in politics, and told

me things that had my hair stand on end to use that hackneyed phrase.

Till then I knew little about the dirty side of politics, but Michello’s

stories were an education to me. I was to check some of his facts

later, and found them all to be quite correct. He had been active all

his life in the politics of the emerging nations of East and South

Africa, and was on first name terms with most of the black leaders of

that time. He mentioned meetings with senior British and American

government ministers and foreign office personnel. He also described

approaches from other power blocks that his then ANC leader rejected,

but which were readily adopted by Kaunda and Kapepwe. The financing of

political parties by foreign powers, and how that finance was used, was

a revelation to me.

The flag of independent Zambia

Independence came in

1964, and Kenneth Kaunda was duly sworn in as Zambia’s first President.

The occasion was marked with great celebrations all over the country,

and our little community had its own festive events with all the people

dressed in their finery and sporting paper copies of the new national

flag. I think I enjoyed the day as much as the native people did. A

few months later, Kaunda paid an official visit to our centre. I showed

him and his party around, and while he was talking to the staff, one of

his black bodyguards approached me. “Your name is Thomson – right?

You have a brother in the Metropolitan Police – yes? Well, - I did my

training with him in London”. Another of those odd coincidences in

Africa.

With President Kaunda (and my wee terrier

dog)

Showing Kenneth Kaunda examples of fish

species from Kariba. The smiling man in the top left corner was one of

the President’s bodyguards who informed me he had trained in London with

my brother James.

The President went off

to an island in the lake for a picnic lunch, accompanied by his

entourage, and by my colleague Michello, and escorted offshore by scores

of powered canoes from our fishing fleet. I went back to the station to

dismiss the staff, still arranged in formation on the parade ground.

stepped out of the Landrover and gave the UNIP vibrating hand wave that

Kaunda had been displaying throughout the visit. The staff (mostly

Tonga) sheepishly returned the wave. Then as I dismissed them and

turned to go away, I gave the ANC two thumbs wave over my head,

signifying - “one man, - one vote”. The tension broke and the

whole assembled body burst into laughter. Africans liked it when you

saw the funny side of things, or appreciated their mixed feelings or

embarrassment.

My experience of life

in Zambia during the tail end of the colonial regime, through the brief

transitional self-government period, and on into full independence, was

a thoroughly pleasant one. I cannot say that any part of it was

difficult or unhappy. The local Africans treated me with respect

regardless of the government. I was once asked by the local ANC

representative to join that party, but this was done in a half-hearted

way, and when I pointed out that as a foreign citizen, I could not vote

in Zambia’s elections, he accepted my position without complaint. But

one post-independence incident might serve to illustrate the general

atmosphere of that time:

There was a man in the

neighbourhood who had a vendetta with one of my staff (the cause of

which was unknown to me – and in Africa, foreigners are well advised to

stay out of such feuds). But he caused a disturbance once too often, so

I took him to the local Boma office and told the guards that I did not

want to see him again near our compound. As far as I know, they put him

on a truck to the plateau. At that time I was about to start training

scores of applicants for government jobs, - in my case for fish guard

positions, - a kind of low level fishery department worker, who wore a

uniform rather like a boy scout. The first truck load of trainees

arrived in a few weeks, and I assembled them for an initial briefing,

and to explain the rules of their stay as far as dormitory, food and

training went.

There, in the midst of

the crowd of trainees, one rather guilty face stood out. It was the

troublesome fellow I had removed from the area. Later that day I got an

eloquent letter (as only Africans can write them), to say that fate had

been so cruel to him all his life, and now, when he finally had the

chance of a permanent job, he had been placed in the hands of the one

person who had reason to think ill of him. I called him to my office,

and puting on a stern face, told him that what happened before was in

the past. He would be judged on his merits in the course. If he passed,

he passed. If he failed, he failed. But I would not hold his earlier

behaviour against him provided it was not repeated. Well, from that

moment on, he became a star pupil, and gave me no trouble whatsoever.

Perhaps rather

unfairly, the government sent me trainees in batches of 50, for whom

there were only about 40 jobs at the most. So the bottom ten were

destined to be rejected, and this fact was not lost on the whole group.

The training programme was quite basic. After being issued with a

simple uniform, the candidates spent the first two weeks in labouring

work, to assess their fitness and their willingness to undertake any

duties, which was really what a fish guard had to do. That was followed

by a week of square bashing with lots of marching and saluting, and

regimentation. Only in weeks four to six did they get to learn boat

handling, engine maintenance, net repair, and fish identification. My

senior fish guard examined them at all stages and presented me with the

results at the end of the course, - so I had no part in the final

selection other than to endorse his findings.

The class referred to

above contained some surly characters from the copperbelt who I suspect

were chosen for their political loyalties rather than their potential as

civil servants. They rebelled at having to do labouring work, and I

guess, surmised that their chances of failing the course were quite high

since the other candidates were much more enthusiastic. Anyhow, they

walked out of the course and off to the capital. I would not have known

what action they then took, except that my friend Jobo Michello happened

to visit the Minister of Natural Resources at that time. Also, I had

sent a truck to Lusaka to collect timber for boat buiding and cement for

making bricks, and had allocated two of the labouring trainees to go

with the driver to help load and guard the vehicle. One of them, I

believe the character who had caused me trouble before, had gone off to

relieve himself before the truck left the city, but it departed while he

was away, and he found himself without transport, and facing a possible

charge of dereliction of duty. In desperation he went to appeal for

help at the Ministry offices.

Apparently the

disgruntled group had asked to see the Minister, and proceeded to

complain that they were being treated like labourers by a white

foreigner, instead of being assured of a government job. The Minister

asked Michello who happened to be around if the complaints against

Thomson were justified. He replied that there was nothing demeaning in

the course, but that those fellows were really not willing to work.

Just then the trainee who had missed his place on the lorry, arrived to

ask for help to return to the Sinazongwe centre to continue his course.

The Minister called him in and demanded to know if the conditions were

bad, and if Thomson was mistreating them. The trainee assured him that

all was well, he had no complaints, but he desperately did not want to

lose his place on the course. The Minister directed his staff to

arrange for the man’s transport, then turned to the striking group and

ordered them out, telling them that they were just downright lazy! As I

indicated above, I would have known nothing about the incident had

Michello not been present, and recounted it to me later.

I departed Zambia in

August 1965, never to return, although I was to visit over a dozen more

African States. Zambia was one of the last of the former British

colonies in Africa to obtain independence. All over the continent,

MacMillan’s “wind of change” was blowing, and it was bringing as much

fear as hope in its wake. Sadly the experience of many of these newly

independent nations has been tragic to say the least. All the cold war

rhetoric about the evils of colonialism has evaporated as those

countries have suffered worse mis-rule, injustice, and greater

exploitation under their own home-grown governments. |