Oh the breezes blowing o’er the sea from Ireland,

Are perfumed by the heather as they blow,

And the women in the meadows digging pratties

Speak a language that the strangers

do not know.For the strangers

came and tried to teach us their ways,

They scorned us just for being what we are,

But they might as well have tried to catch a

moonbeam,

Or light a penny candle from a star.

And if there’s

going to be a life hereafter

As somehow I am sure there’s going to be

I will ask my God to let me make my heaven

In that dear land across the Irish

Sea.

Galway Bay*

“So near to home, - so

far from care”.

Thus the Irish tourist board describes the Emerald

Isle to potential visitors from Britain. Despite its turbulent

history and troubled present (in some parts of the north), Ireland has

been and remains a happy country with a delightful people. The Irish are

welcoming, and hospitable. They love to sing and to converse, and are

at their best when expressing their priceless humour. They are a

down-to-earth people, generally unsophisticated and unpretentious, but

that does not mean they lack perception, and if Paddy senses you are

trying to trick him, he will string you along as though totally unaware

of your intentions, but in the end will turn the tables on you with

remarkable skill.

I used to visit Ireland during the summer holidays from

school when I was given a much prized opportunity to serve as a cabin

boy on the family boat. I remember fishing in Galway Bay when sailing

hookers carried peat around the Arran Islands and Connemara, and

when curraghs were rowed out into the Atlantic to fish for

basking sharks. The curragh was a light canvas covered boat with

a high stem and flat stern, and fine seaworthy lines for coping with the

Atlantic swells. The master boat builder with whom I was privileged to

work on Lake Kanba, Dick Heath, chose the lines of the curragh as

a basis for the planked canoe he designed for Zambia’s fisheries. It

proved to be an excellent boat for the sometimes short sharp waves on

the large lake. But back to west Ireland, - we spent the odd night in

Kilronan in the main Arran island of Inishmore. At the home of Mrs

Joyce, a prominent lady of the island, we sat around a peat fire on a

stone floor under an oil lamp, and were served tea and home bakes. As a

special treat I was given a glass of milk. It tasted odd to me, till I

realized it was goat’s milk. Connemara was another fascinating area

where houses and dress had changed little in centuries. When I go to

Ireland now, it amazes me that there seems to be not a single old

thatched cottage left there, - just one large modern bungalow after

another.

Old Galway harbour

Aran Isles, the town of Inisheer

My father’s family

loved the Irish. Four of the family boats fished round the coast there

several years for a Dublin firm. Every port they went into, they were

met with kindness and friendship. In the 1940’s and 50’s Ireland was a

poor country, - a far cry from the ‘yuppy’ society one sees in Dublin

today. I used to think it surprising that those Scots fishers, - mostly

fundamentalist, non-conformist types, were so drawn to the devout

Catholics of the Republic, - and the Irish Catholics to them. But so it

was. Mercifully, the tensions in Ulster did not affect their

relationships. The Scots were regarded as fellow-Celts, and if their

home-spun religion appeared strange to the devout Roman Catholics, they

still recognized a common bond of faith, uncontaminated by political

agendas.

Ireland suffered from

the time of Henry VIII due to it being regarded as a potential enemy or

supporter of the Catholic powers in France and Spain that threatened

England from time to time. Not that England did not threaten Europe

also. – reading the history of those costly and pointless wars with

France and Spain, - it all appears so foolish now. But through the

reigns of the Henry’s, Elizabeth, James 1st, Charles 1st,

Cromwell, Charles 2nd, and on to King William of Orange and

the George’s, - how Ireland suffered, - used by the continental powers,

and punished in return by England. All this led to much absentee

landlordism, and prevented the development of truly representative local

government.

The four vessels operated by H J Nolan’s

and the Thomson family, 1949 to 1956. They were Moravia, Casamara,

Kincora and Kittiwake.

The country was never

wealthy, it had an exploitative land-owning class, and there was little

industry except in the north, and that developed after the plantation of

protestants from the Netherlands and Scotland first by James 1st, and

later by William of Orange. Then came the dreadful potato famine of the

early nineteenth century, when hundreds of thousands died of starvation,

and many thousands emigrated. Yet through all those troubles, Ireland

supplied much cannon fodder for English or British armies, and much

cheap labour to further the industrial revolution. The surprising thing

to me, is not the strength of Irish nationalism, or the growth of a

small but murderous IRA, - the surprising thing to me is the amount of

goodwill towards England that still exists throughout the emerald isle.

The horrors of the

potato famine are largely forgotten today, yet they occurred a mere 150

years ago. Whether the potato blight caused by a fungus Phytophthora

infestans could have been prevented or controlled at that time is

doubtful, but what most certainly could have been avoided was the death

by starvation of close on a million persons, and to some degree, the

emigration of close to another million in desperation for survival in

foreign lands. Four and a half million pounds left Ireland annually at

that time, in payment of rents to absentee landlords, - far more than

was needed to feed the population during famine.

|

A glimpse

of the Irish famine, 1846 – 1851

In a

report to the British Parliament, one of the first to put on

official record the stark facts arising from the starvation of

thousands upon thousands of Irish peasants, told of the horrors

taking place that till then were largely hidden from the British

public, and tragically ignored by authorities :

“Tipperary

is in insurrection, Clonmel in a state of siege, government

bayonets displayed. The people’s food is locked up. Hilltops

are covered with thousands of men, livid with hunger. Provision

boats are boarded, mills and stores ransacked. Galway, Cork,

Clare and Limerick are counting their deaths from starvation.

Families in Cavan are resolved on a suicide of starvation to

escape beggary. Thousands wait for typhus or other hideous

phantom to rescue them from the griping horrors of want.

Meanwhile the British Government vacillated and observed

complacently that ‘in many of the most distressed districts,

the patience and resignation of the people have been most

exemplary’,”.

An

eyewitness reported more graphically, “We are here in the

midst of one of those thousand Golgothas that border our island

with a ring of death from Cork to Loch Foyle. There is no need

of enquiries here, no need of words. Grass grows before the

doors and we fear to look inside lest we see yellow chapless

skeletons grinning there. We walk amidst the houses of the dead

and out at the other side of the cluster, and there is not one

where we dare to enter. They are all dead: the strong man and

the dark-haired woman and the little ones with their liquid

Gaelic accents. They shrunk and withered together till they

hardly knew each other’s faces. The father was on a ‘public

work’ and earned the sixth part of what could have maintained

his family, which was not always paid to him. But it kept them

alive for three months, and so, instead of dying in December,

they died in March”. [Quoted

in chapter 8, ‘What Parliament Did’, in The Trial of Patrick

Sellar by Ian Grimble, R Paul, London, 1962.] |

Tradition tells us that

it was an Irish monk who first brought the Christian gospel to

Scotland. He was Colum Cille or Columba as he is now known. His

original settlement in Iona has been restored and now functions as a

non-denominational centre of Christian ministry and concern for the

third world. Irish monks preserved the Christian faith through the dark

ages, in their lonely abbeys and hermitages built in the most isolated

rocky islands or remote hillsides. Irish priests and poets enriched

European culture for centuries. And some surprising non-Catholic Irish

writers and theologians had an influence on Britain. It was a Church of

Ireland cleric, John Nelson Darby that founded what came to be known as

the Plymouth Brethren. Their first meeting place was in Merrion Hall,

Dublin, - not in Plymouth. Another prominent evangelical, brilliant

Irish lawyer and theologian, Sir Robert Anderson, was head of the

Scotland Yard CID in Queen Victoria’s time.

Connemara in the

1950’s. An old Hooker sailboat in Galway Bay

(It does not look like that today)

My favourite Irish poet

is W B Yeats, who was also a playwright and a mystic. I spent some time

around his beloved Sligo when fishing out of Donegal Bay, and often

thought of him when admiring the heights of Ben Bulben beneath which he

is buried at Drumcliffe. Most of Yeat’s poetry is pleasant and

romantic. “When you are old and grey and full of sleep”, is one

of the most touching of love poems. But Yeats had his mystic and

prophetic side somewhat like Blake and Shelley, and there are a couple

of lines from his poem, “The Second Coming”, that I feel are

sadly relevant to these dark modern times :

“The best lack all conviction, while the

worst

Are full of passionate intensity.”

Irish music also

stirred me as did Scots plaintive songs and pipe tunes. The Irish have

an abundance of folk songs (of varying quality), that are best heard in

a singing pub of which there are many scattered throughout the land.

When I first visited the country, it was a common place event to have a

young lad wander off the street and start to sing in a corner of a pub,

with no musical accompaniment, and in some cases, rather little

ability. I guess it was one of the few ways they could pick up a few

pence then. Public houses had their own character in Ireland. They

were not the hard drinking places that one found then in Scotland, but

neither were they the more genteel tavern – restaurants for which

England is renowned. Most Irish pubs served only drink, but they were

social centres where people gathered to share the news of the day. They

also served delicious ‘club orange’ and ‘club lemon’ drinks. I have

tried them since, and somehow they don’t taste the same today.

Of Irish historical and

non-fiction books, I have mentioned two in the following box. Both were

written out of hard experiences of poverty and injustice, - one in the

North and one in the South of Ireland. Both have been recognized as

classics in their own way. Reading them even today is a moving

experience.

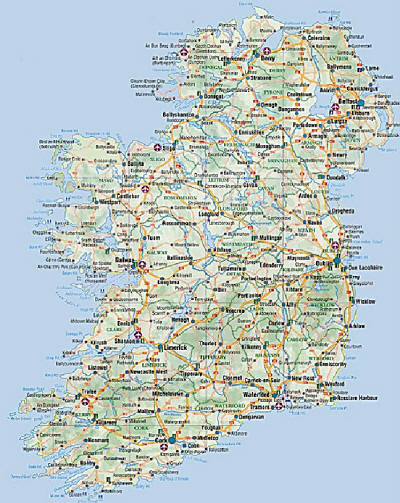

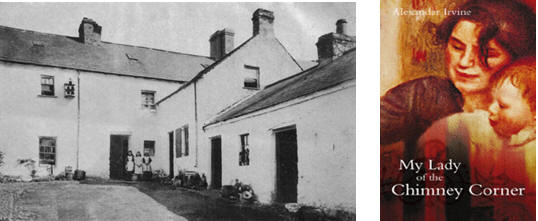

Pogue’s Entry, Antrim, birthplace of Andrew Irvine. His moving book

My Lady of the Chimney Corner.

Above : Andrew Irvine

|

Memorable

Irish Books and Films

If there

is a book that portrays the beautiful side of the Irish people

more than any other, to me it is Dr Alexander Irvine’s

poignantly inspiring portrait of his mother who lived in Pogue’s

Entry in Antrim. – “My Lady of the Chimney Corner”. [My

Lady of the Chimney Corner,

First published in 1913. Republished 1993 by the Appletree Press

Ltd, Belfast]. His

parents, of poor peasant stock, were unusual in Ireland – from

opposite sides of the religious fence, - farm labourer Jamie a

Presbyterian and Anna a Catholic. In consequence, neither

attended their churches much thereafter, but both displayed

remarkable Christian faith and character through periods of

severe poverty. For years, their little house was a haven of

consolation and encouragement to the local people in Antrim,

hospitality and counsel being administered liberally with rich

helpings of couthy Irish humour.

The home

is now a museum, and Anna and Jamie are buried in the churchyard

nearby. Irvine described his moving book as only “the torn

manuscript of the most beautiful life I ever knew”. He

wrote, “I have merely pieced and patched it together, and

have not even changed or disguised the names of the little group

of neighbours who lived with us, at ‘the bottom of the world’.”

Another

book, less well known outside of Ireland, is “Paddy the

Cope”, [My

Story – Paddy the Cope,

Patrick Gallagher’s autobiography, c.1947, reprinted 1979, by

The Kerryman Ltd Tralee, for the Templecrone Cooperative

Society, Dungloe.] the amusing yet instructive autobiographical story of

Patrick Gallagher who founded and ran one of the country’s most

successful rural cooperatives. Gallagher was illiterate, and the

book is written as taken from his verbal accounts, with all the

grammatical forms and the

pronunciation

he used. But the book is a remarkable account of the resilience

of a community intent on achieving some control of their

economic future, in the face of powerful local vested

interests. I referred to it often when encouraging poor fishers

in Africa and Asia to work together to improve their lot. It

was surprising how well they related to the Donegal farmer, and

the constraints and obstacles he overcame in life.

One of my

treasured possessions is a concert programme signed by all of

the actors in the film The Quiet Man, and by its Director

John Ford. The family boats were fishing out of Galway and

Connemara in 1952 when the film was made, and they lent some of

their new fish boxes to make a stage for the concert which was a

kind of a thank-you by the cast to the local people. John

Wayne, Maureen O’Hara, Victor McClaughlin and Barry Fitzgerald

were among the stars of this light and entertaining picture of

life in rural Ireland in the 1930’s. When first released, the

film played to packed audiences in Dublin, night after night,

continuously for three years.

Much later

I was to see the film “Michael Collins” on the Irish

struggle for independence and the tensions between De Valera and

Michael Collins (played by Liam Neeson) which led to Collins

death. It is a moving film, spoiled for me by the way the

crowds were dressed – they were attired more like middle-class

Americans than Irish of 1922 – few black shawls and no homespun

trousers.

We were

often in O’Connell Street Dublin where much of the early IRA /

British fighting took place, and in the main Post Office which

still bears the bullet marks from 1916 when it was held for a

period by Patrick Pearse and a contingent of the Irish

Nationalists. In the middle of O’Connell Street was a huge

stone column with a statue of Lord Nelson. We used to climb the

steps inside to get a glorious view of Dublin from the top.

Nelson’s Column is gone now, blown up by the IRA over 30 years

ago. Below : the

Post Office and Nelson’s Column.

Dublin Post Office, O’Çonnell Street, where

Nelson’s monument O’Connell Street,

much fighting took

place in the early 1920’s

1955, later blown up by the IRA |

On a visit to the House

of Commons in 1990 at the invitation of Lord Winchilsea [Sir

Christopher Denys Stormont Finch Hatton, the Rt Hon the Earl of

Winchilsea and Nottingham, Liberal Peer.],

we went to get a cup of tea at one of the many bars in the House, I

found myself face to face with a bust of John Redmond, the highly

respected Member of Parliament for Waterford, and Chairman of the Irish

Parliamentary Party who did much to facilitate the granting of

self-government and later independence to the Irish Republic. I had

stayed with the MP’s niece, Maud Redmond, for a summer holiday in 1954.

She was a retired music teacher who had worked in that capacity for the

Austrian Empress and her family in Vienna before the outbreak of WW1.

Miss Redmond’s cottage was full of priceless antiques, and she was kind

and patient enough to introduce me to that world. She taught me how to

recognize gold and silver stamps, Sheffield plate, Adam’s fireplaces and

Chippendale furniture. She was secretary of the local RSPCA and loved

animals, her favourite being a Shetland collie that my father had

brought over from Scotland. Miss Redmond was never happier than when she

would fill her room on a Saturday evening, with the finest musicians

from Waterford, plus the motley crew from our fishing boat. She was as

delighted with the crewmen’s attempts to serenade or recite doggerel

poetry, as she was with the accomplished performances of her musical

friends.

Dunmore East harbour light with the Hook

lighthouse in the background

Looking back, the

fishing system used in Ireland over 50 years ago, compares well in terms

of quality and freshness of produce, with any in use today. The four

Scottish boats that supplied H J Nolan’s with fish, would gut, wash,

select by size, and pack, whiting, cod, haddock, hake and flatfish in 7

stone (98 lbs) boxes with ice, and cover them with a sheet of

greaseproof paper. When fishing in the Atlantic off the Arran Isles,

the four boats would inform the Galway agent daily by radio of the

catches and he would telephone Dublin for an appropriate amount of empty

boxes and ice. The fleet would come inside the islands to put all their

catches on a single boat that would then take them the 3 hours to Galway

where the fish truck from Dublin would be waiting. After unloading, the

vessel would take ice and boxes back for all four boats. Each boat

would take its turn in making the Galway trip. In this way, there was

fresh fish on Dublin market at 6.00 a.m. each weekday morning, that had

been caught the previous day in the Atlantic off the west coast. I

doubt if any market in Europe can surpass that standard for fresh fish,

even today.

My best personal friend

in Ireland was Sean Cotter of Castletown Berehaven in County Cork.

Along with myself he was an apprentice deckhand on my father’s boat in

the mid-1950’s. A gem of a fellow, Sean (Johnny) had a rich store of

tales from that wild and remote south-west part of Ireland, which he

would relate with appropriate colour and exaggeration. He was as cool

as a cucumber when encountering more sophisticated society. I will

never forget him bargaining with a draper in Dun Laoghaire for the

purchase of a suit. No Jew or Arab could have beaten the price down

better or gotten more extras out of the draper than Johnny did. He was

a fine seaman, and later went on to become a successful skipper of a

French-built trawler fishing on the wild Porcupine Bank in the Atlantic,

west of the Arran Isles. After a gap of forty years I had an

opportunity to go to Castletown and look him up, and found him aboard

his vessel in the harbour. He did not recognize me at first. When I

said I was “one of the Thomsons from Lossiemouth”, he responded,

“do you know David?, - how is David these days?”. Within minutes

I was given the royal treatment, and ended the evening in his bachelor

house round a roaring fire while his crew brought up huge fresh Irish

ham sandwiches from the shop and Sean poured mug after mug of hot

steaming tea. He had given up drinking for health reasons some time

before, but had never married. He lost his life a few years ago, sadly,

but somewhat appropriately, at sea. He had semi-retired to a one-man

boat, the Kyle Mhor, which he fished with skill, but something went

wrong that last morning, 31st May 2000. The vessel capsized

south of Black Bull Head, and he was drowned. The fishermen of

Castletown called me and gave me a moving account of how they bid Sean

their last farewell. His sister and brother-in-law in England, also

wrote of him with deep affection and admiration. Sean was the third of

three young Irish fishermen I knew in 1955 who all lost their lives at

sea.

Another fine young

Irishman I got to know was Pat Kelly-Rogers. Pat was the son of Captain

Kelly-Rogers, then the head of Aer Lingus, the Irish airline. During

the war years he had been Winston Churchill’s personal pilot. I had the

privilege of meeting Captain Kelly-Rogers through his son Pat. His

daughter Aine also became a friend of my wife’s. Pat could have had any

career he wished I think, but he loved the fishing. He had served in

the US Navy during the Viet Nam war, but came back to Ireland to pursue

his real interest. He served for a while as a crew member on a herring

trawler I operated for a year in Ireland. Later he acquired a boat of

his own, and fished well for a period, but lost the vessel following a

collision at sea when pair trawling for herring off the south coast.

Pat Kelly Rogers on left helping

with a mixed bag of mackerel, herring and haddock on the Dayspring

off Donegal. The Mate, Peter Smith of Buckie is on the right.

Peter later became a successful skipper of inshore, coastal, and deep

sea vessels around Scotland and abroad.

Taking locals out for the blessing of the

bay, Galway, 1950

In Dunmore East there

was an interesting character engaged in both fishing and the sale of

nets and chandlery. He was Alan Glanville from England, who had served

with FAO in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in the early 1950’s, along with Einar

Kvaran of Iceland with whom I worked years later in Indonesia. Alan had

also worked with John Garner and Gourock trawls on the early development

of wing trawls in Britain. Alan was regarded as a “gentleman fisher” by

other fisherman as he went to sea only when it suited him and when it

was profitable. However, he did well in Dunmore East, both at the

herring fishery and in selling nets and gear. I was to meet Alan

occasionally at fishery exhibitions and when visiting the south coast.

At the age of 75 Alan was operating a steel vessel off the south-west

coast, fishing for bluefin tuna by deep sea rod and line. He was then

thinking of establishing a tuna ranch in one of the Irish bays.

Following the tsunami disaster in SE Asia, at the age of 80, Glanville

had some fishing boat hulls of suitable design built in Chile and sent

from there to the fishermen of Sri Lanka.

Other fishermen in the

Republic who I came to know and admire included James McLeod, a

qualified merchant navy captain and airplane pilot, who pioneered

herring fishing in the west, and set up a net factory in Killybegs.

James lived to over 90 years of age, and when he was no longer permitted

by age to fly aircraft, he took to piloting gliders. Albert Swan was

another skilled fisherman, who established the large Swan net company.

Then there were the McAllig brothers from Dunkineely who operated

several trawlers. Willie McCallig was a crew member on my father’s boat

when we fished in Ireland. He was killed in a car crash along with a

relative, in 1994. In Castletownbere there were the O’Driscoll

brothers, and in the Aran Isles, Pat Jo O’Donnell, Pat Jennings and

Keiran Gill.

Ulster, (Northern

Ireland), was not a part of the island I visited much, though my father

had fished before from Ardglass and Portavogie. There was one family in

the north we knew well, and sometimes visited, as they had many

connections with Scotland and with my father and his brothers. They

were the Chambers family of Annalong, a village beside Kilkeel in County

Down. Jack Chambers was the oldest brother, but Victor was the leader,

and a real pioneer in Irish fisheries. He had four vessels in

succession, each breaking new technological ground in the capture of

demersal fish and herring. The family boats had names like Green

Pastures, Green Isle, and Green Hill. Recently I met a grandson of

Jack Chambers in Malaysia where he was serving on an ocean going mission

ship.

Ireland is a favourite

holiday destination for our family. My wife and I particularly enjoy a

week on the Shannon – Erne waterway where you can rent a small cabin

cruiser for less than the cost of a bed and breakfast room for two, and

cruise up or down most of the length of Ireland, in leisurely fashion

and surrounded by pleasant scenery and interesting bird life. Truly, -

so near to home, and so far from care.

All of the above, I

hope, paints a cameo picture of the land of the shamrock and its much

admired people. But it is a background against which I would like to

consider the problems of Ulster and the bloody work of the IRA and the

UDA. Sadly, few national symbols are more prophetically accurate than

the ‘red hand of Ulster’. I knew many Irish nationalists, - in fact

there are few in southern Ireland that would not fit that description.

I also knew several members of the IRA, and more indirectly, some

members of the UDA. Once I sat beside the formidable MP and Free

Presbyterian Minister Dr Ian Paisley on a flight from Rome (of all

places) to London. He was a most courteous and congenial traveling

companion, and I was surprised to learn that we had some acquaintances

in common.

Structural injustice

has led to civil disobedience and violence in many countries. The cries

of Unionists in the North, for Irish Catholics to obey the laws of the

land, reminded me very much of similar injunctions (in pre-Apartheid

days) from whites in South Africa, to their disadvantaged black

citizens. The attitude of hard-line whites in the American south to the

civil rights movement of the 1960’s is another example. Historical

injustices have to be rectified. That is why the root cause of the

Irish troubles are often referred to as “the sins of our fathers”.

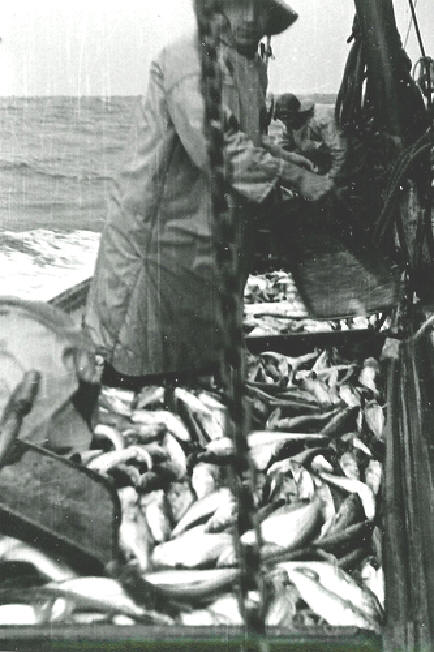

A bag of saithe (coley) west Ireland,

1949

Domination of Ireland

by successive English and British Governments from the time of Henry the

8th, has caused untold sorrow. The fierce vengeance of Cromwell’s and

later King William’s armies, and the plantation of Protestants in

Ulster, centuries ago, sowed the evil seeds of the current tensions and

conflicts. While British attempts to create coalition governments in

Ulster have been regarded with suspicion or lack of cooperation by

political parties there, a sea change is taking place as the Republic is

no longer the ‘poor brother’ since it joined the EU and became a

prosperous financial centre. Unionist determination to stick with the

United Kingdom has been weakened by Britain’s industrial decline, and by

the coolness of UK governments towards Ulster.

I recall sitting next

to a young red-headed IRA activist in London airport in 1965 while he

railed to his lawyer about the British Government having killed his

father, and how he owed them no allegiance and they held no authority

over him. I had another zealous IRA man join my crew on a trawler I

fished briefly from Killybegs, but he turned on the organization when it

tried to get his brother to go on a hunger strike to the death. The

problem for Eddie was that those who wanted his brother to die that way,

in his opinion, would not miss a meal themselves for the cause.

One of the fishing

boats part-owned and operated by my uncles when working with H J Nolans

in the early 1950’s, the Casamara, was used to carry arms

shipments from Libya to the IRA in 1985. That was long after Nolans

sold the vessel. Commanded by an Adrian Hopkins of Dun Laoghaire from

where we often fished, Casamara was reported to have made three

arms shipment voyages in the year in question, carrying from 10 to 16

tons of weapons and ammunition, including AK 47 rifles, pistols,

anti-aircraft machine guns and rocket launchers. Also in the cargo were

a million rounds of bullets and thousands of mortar shells. General

John de Chastelain who inspected arms that the IRA had put out of use,

identified some as coming from the Casamara shipment. I find it hard to

believe that that lovely 65 foot seiner built by Tyrrell’s of Arklow in

the late 1940’s, which was manned by such fine crews of fishermen and

which had harvested fish all round the emerald isle for 30 years, was to

be used for the murderous weapons trade in the 1980’s.

The Casamara when operated by Nolan’s and

the Thomson family.

Some 20 years later it was used for gun-running by the IRA.

Hopkins was reported to

have used three different vessels over a 2 to 3 year period, - the

Casamara, the Villa, and the Eksund. At one time he

changed the Casamara’s name to avoid detection. He and his

Eksund crew, including IRA member Gabriel Cleary, were arrested by

French authorities in the Bay of Biscay in 1987, and spent the next 3

years in French jails. Released on bail, Hopkins made his way to

Ireland where he was picked up by Gardai police in Limerick. Numerous

reports, including Ed Moloney’s 2003 book, The Secret History of the

IRA, claim that the arms shipments were financed and organized by

one Thomas ‘Slab’ Murphy, a wealthy pig farmer whose property adjoined

the Irish Republic border. These reports describe Murphy as a veteran

IRA commander, and its most lucrative smuggler. It was also suspected

that he was behind the brutal murder of Eamon Collins near Murphy’s

farm. Collins had been a witness against Murphy in a British court

case.

Thomas Murphy was said

to have been on the beach at Clogga Strand in County Wicklow when the

Casamara discharged her cargo of weapons and ammunition. In 2006,

Northern Irish and Republican police raided Murphy’s farms after British

police had searched over 240 properties in England, valued at £ 55

million, that were believed to be part of an IRA money-laundering

operation.

Most Irish Catholics

supported the movements to rid all of Ireland from the UK, though only a

few would agree with the violent means of the IRA. So it was hardly

possible to have a Catholic Irish friend who did not harbour national

symathies. Rather, I suppose as it would be difficult to find ordinary

Arabs in the Middle East who did not want their lands to be free of

American or Israeli domination. Despite all of the violent background,

and the historical injustices that have beset Ireland, rather

wonderfully, even avowed Catholic nationalists and Protestant unionists

can be great friends cooperating effectively and in harmony. I knew

some who were in that category. Two who come to mind, Paddy Smyth and

Bobby McCullough, a fish merchant and a skipper of a large vessel,

worked marvellously together, though they constantly teasing, and

playing practical jokes on one another. The core problem of Ireland is

political, not religious, and it relates to basic justice.

Nevertheless, the

political divides are drawn largely along denominational lines, and so

Catholic – Protestant tensions live on in Northern Ireland where it

would seem that the Reformation and the European religious wars occurred

only yesterday. Elections in Ulster are seeing a polarization of votes

for the extremist parties, the DUP and Sinn Fein. Both the propagators

of armed struggle and armed resistance, use religion for their political

ends. For all the sworn adherence of the IRA to the church, or of

extreme Protestants to Biblical truth, both parties in Ulster would do

well to take to heart the words of Pope John Paul II in Drogheda 1979 :

“Violence is a lie, for it goes against the truth of our faith, the

truth of our humanity, the life, the freedom of human beings. Violence

is a crime against humanity for it destroys the very fabric of society.

O my hearers I beg you to turn away from the paths of violence and to

return to the ways of peace.”

The solution to

Ireland’s problems lies with the Irish, with the thousands upon

thousands of peace-loving men and women and young people, and with those

who once practiced violence but have since renounced it. Men like

former loyalist para-military Billy McIlwaine, and women like former

republican para-military Mary Smyth, and the Soldiers of the Cross

movement they supported. Billy McIlwaine, former man of violence has

written: “I appeal to the men and women in the various paramilitary

organizations to examine in their hearts what they hope to achieve by

violence and bloodshed in Northern Ireland. … Is there not a better

way? Is there not another way than the bomb and the bullet? I love this

country and its people, and I pray that Catholics and Protestants,

Loyalists and Republicans, might live together in peace”.

A peaceful future is

being carved out of the landscape of bitterness by courageous people

like the women who campaign tirelessly for peace, and organizations like

the the Corrymeela Community of Christians for justice and peace. There

are also outstanding men like Dr John Robb who as a surgeon at Lismore

Hospital Ballymena, had often to repair the horrendous damage done to

human bodies by the indiscriminate bombs. His father Dr John Charles

Robb, a pioneer in medical and hospital work, served in Downpatrick

Hospital for many years. My father was placed under his care in 1953

when he was landed unconscious from a brain hemorrhage due to excessive

hours at sea without sleep. Thankfully, my father recovered, and in the

process he got to know the Robb boys, Johnny and Jimmy, both of whom

spent some time at sea with us later when on vacation. They were great

fun, keen rugby players, and real gentlemen. Both graduated as medical

doctors, though Jimmy had intended a different line of work, but changed

to medicine after a life-changing visit to Calcutta where he observed

human misery and suffering to an extreme degree.

Johnny became a

renowned surgeon, often operating on bomb victims at Lismore Hospital as

mentioned above. He was made an honorary Senator by the Dublin

Government in appreciation of his efforts to promote peace in the

north. I mentioned his name to the Rev Iain Paisley during the

conversation we had on a flight to London. The leader of the Democratic

Unionists said, “ah, ... - he’s all mixed up. But, … he is a very

good surgeon”.

MFV Dayspring en route Ireland

from Norway |