|

I must go down to the seas again, to the

lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship, and a star to

steer her by;

And the wheel’s kick and the wind’s song, and

the white sails shaking,

And a gray mist on the seas face, and a gray

dawn breaking.

I must go down to the sea again, for the

call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be

denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white

clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the

sea-gulls crying.

I must go down to the seas again, to the

vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull’s way and the whale’s way, where the

wind’s like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing

fellow rover,

And quiet sleep and sweet dream when the long

trip’s over.

John Masefield

I really don’t know why it is that all of

us are so committed to the sea, except I think it is because … we all

came from the sea. And it is an interesting biological fact that all of

us have, in our veins the exact same percentage of salt in our blood

that exists in the ocean and, therefore, we have salt in our blood, in

our sweat, in our tears. We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back

to the sea, whether it is to sail or to watch it we are going back from

whence we came.

. President John

F Kennedy, Newport, Rhode Island, 14 September 1962

The picture of the old salt with the tall hat and

leather boots, sorting his lines, is of my great grandfather, Alexander

(‘Sanny Caccy’) Thomson; (Caccy or Caukie, as he was one of the few

Catholics in the community). My forebears on both sides were fishers,

as far back as we can trace. Those of my great grandfathers’ time were

line fishermen operating sailboats, Scaffies, Fifies and Zulus,

[The

scaffie had lines like a Viking sailboat, the fifie had a

straight stem and was built to grip the water better when sailing close

to wind. The zulu incorporated features from both, and proved

ideal for drift net fishing. Some books tell of the design being a

compromise between a strong-minded fisherman and his equally

strong-minded wife. I met ‘Dad’ Campbell, the then aged son of

the zulu designer William Campbell, in Portland Oregon in

1968, and asked if there was any truth to the tale, but he dismissed it

as jesting gossip.]

and shifting to the drift net for herring in the appropriate season. My

grandfathers operated drifters, both motor and steam driven, and these

larger boats worked year-round for herring.

The town of Lossie was

built chiefly on herring. From about 1900, merchants and farmers loaned

fishermen the money to build the drifters, and the community prospered.

The fleet worked off Norfolk and Suffolk in the autumn, Dunmore East,

Ireland in the winter, then the Moray Firth, Shetland and the Minches in

the spring and summer.

The bulk of the herring catch was gutted, dry-salted, and

packed in barrels. That continued till after the 1914 – 18 war when the

changes it brought to the economies of Russia and East Europe, meant a

collapse of the huge export market for salt herring. So the drifters

were gradually abandoned, and the fishers turned back to white fish

again (haddock, cod, hake, flatfish). This time they looked for a more

productive method than line fishing, and they found it in the Danish

seine net.

Great

Grandfather, Alexander Thomson, ‘Sanny Caccie’ Old Scots sailboats

(Peter Anson’s drawings)

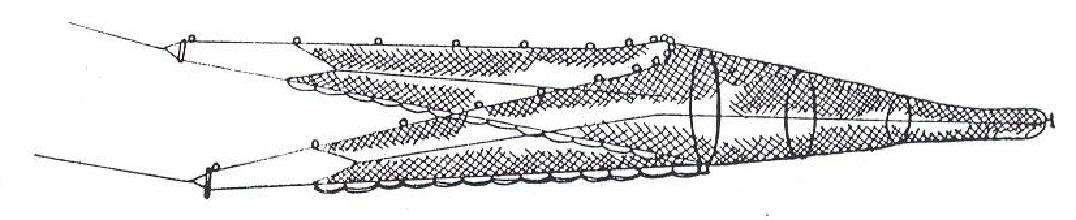

The Danish seine or “snurrevod”

was a light long-winged bag net that could be pulled over the

sea-bed by small, lightly-powered boats. The net was kept open

horizontally by a mile of manila rope, set in a semi-circle on each

side. The ropes were winched in slowly till the wings of the net came

together, by which time any fish encircled by the warps had been herded

into the net which was speedily hauled to the surface. The Danes

winched the gear in while their boat was held fast to a large anchor.

Scots fishers preferred to tow the gear slowly forward while the ropes

were slowly warped in. The Danish method suited the capture of plaice,

their chief target. The Scottish ‘fly-dragging’ method permitted the

net to take faster and higher swimming fish like haddock and cod. Along

with most of the east coast fleets, our local boats adopted the gear

which soon proved to be a money-earner, in place of the abandoned

herring nets. By the time I left school, Lossiemouth had the largest

seine net fleet in Scotland. The local harbour could scarcely

accommodate all the boats, and many fished from west coast ports like

Oban, Lochinver and Kinlochbervie. Larger seine netters were later to

use Peterhead as their base.

Below :

Drawing of a seine net in operation.

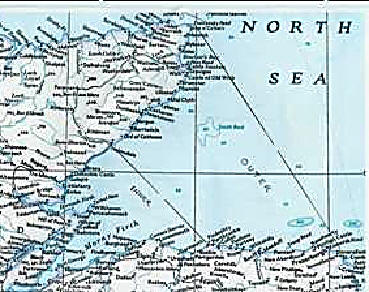

Above : The Moray Firth, inner and outer

sections

I recall the premier

showing of an underwater film of the seine net in operation, in 1953, in

our home town. The film had been shot in the shallow waters of Burghead

Bay by a renowned Naval frogman Commander ‘Buster’ Lionel Crabb RNVR GM

OBE whose disappearance some 3 years later has been the subject of much

speculation. His life ended mysteriously when he went swimming around a

Russian Naval vessel at Portsmouth in 1956. [The

Russian naval ship was the Ordkhonikidze. The previous year Crabb

had inspected the heavy cruiser Sverdlosk, that was carrying

Soviet leaders Bulganin and Kruschev for a meeting with the British

Labour Government (at which Kruschev behaved in typical fashion).

Little information or explanation of the Ordkhonikidze incident

was released at the time by the British and Soviet governments, though

there was much speculation, and Prime Minister Eden later forced MI6

Director John Sinclair to resign over the matter. (I have talked to two

former RN divers who claim that Crabb was taken to the Soviet Union

where he died or was killed for his non-cooperation.) He had undertaken

a number of dangerous assignments for the British Navy during the second

world war, for which he was highly decorated.] Anyhow, the film he shot in the Moray Firth was shown in

the local town hall to a fascinated audience of fishermen and would-be

fishermen. It was one of the first films to record fish actually being

caught in a trawl-type net. The technology however was still at a low

stage of development. The nets were small and made of cotton. Within

ten years they were to be replaced with synthetic high-opening trawls,

and the rope warps were also to be made thicker and of synthetic

material.

Commander ‘Buster’ Lionel Crabb RNVR GM

OBE who first filmed the seine net in operation under water and later

lost his life under a Soviet naval ship.

But all that was in the future. When I went to sea, the

technology was fairly simple, though to me, a young lad, there were no

finer boats on the sea, and none better at catching fish. The Scottish

fishing ports and fishing fleets shared a remarkable camaraderie and

culture that was a world apart from sheer money-making or soul-less

materialism. It was a way of life. Fishermen loved their profession;

they were proud to be members of the sea-faring community. As a visitor

remarked perceptively, “there is an ‘esprit de corps’ about them”.

In those days there was no Sunday fishing [Here

I speak only of the family-owned seiners and ringers. Company-owned

trawlers were a different matter.]

The vessels sailed at midnight Sunday, and not a minute before. It was

a great sight then to stand on the pier and watch the fleet sail “out

into the darkness, and eastwards to the dawn”. The first evening

stroll I took with the lovely young lassie who was to become my wife,

was to watch the fleet depart on such a night. That was after I had left

the sea. For the first seven working years of my life, I was on the

boats watching the crowds wave to us from the pier as we set off on our

weekly fishing trip. The practice died out in the 1970’s. Today much of

the fishing fleet works on Sunday as on other days of the week. Yet

there are still some fishermen who respect the day of rest, mainly in

the Hebrides, but also among some devout east-coasters.

Once at sea, the radio-telephones were switched on, and the

men on first watch, (usually the younger deckhands), began to talk and

sing to each other. It was mostly hymns and gospel music they shared.

The singers were not necessarily strong church-goers, but it was the

done thing nevertheless. Often they acquired their knowledge of

spiritual songs in fishermen’s missions, gospel halls, or Salvation Army

meetings. But it mattered little what their background had been, the

hymn singing was a fishers‘ thing, not a church thing. The singing and

exchange of news continued till daylight or till they reached the

fishing grounds and work began in earnest.

Since my father was

then fishing around the Republic of Ireland, my baptism was to take

place in that fishery, and we had to voyage across to the emerald isle.

We sailed into the Moray Firth and west to Inverness from where we went

through the Caledonian Canal built by the great civil engineer Thomas

Telford in 1822, and on down past Fort William to Oban. From Oban we

sailed south-west, and then west past the southern end of Mull, and the

famous Stevenson-built lighthouses of Dubh Artach and Skerryvore near

where the brig Covenant was said to be shipwrecked in RLS’s

marvelous tale “Kidnapped”. From there we punched our way across

the north coast of Ireland, in the teeth of a north-westerly gale, and

then headed south to Rosan Point and Rathlin O’Birne island, then east

into Donegal Bay. Arriving at Killybegs harbour after 12 hours of rough

passage, we were glad to make port, myself especially, having gone

through the throes of sea-sickness most of the way. But within a few

weeks I had my sea-legs, and was working on deck with confidence, and

with an appetite that rough seas could not diminish. Over the next year

we visited most of the fishing harbours in the Republic, and caught our

share of haddock, cod, whiting, hake, skate, gurnards and soles. We

even spent a winter at the herring in Dunmore East on the south coast.

My father, Skipper Jimmy Thomson

Visit of the Queen to our harbour, 1956

Each December and January, huge schools of herring came to

the Waterford coast to spawn. Fleets of large trawlers and drifters

fished for them offshore, ring netters and seiners worked on the schools

close to land, and Dutch luggers, many with crews of young boys from

orphanages, brought the herring which they salted on board in barrels

and took back to Holland for additional curing. The herring were so

thick on the sea-bed at times, they could be caught with almost any

gear. We sewed small-meshed herring bags on to our seines and were soon

filling them with up to 20 tons of herring a time. Some tows there were

more, but the cotton bags simply burst. We sold some catches in

Ireland, and sailed over to Milford Haven in Wales with others to obtain

slightly higher prices from processors like Birds Eye. The weather in

winter on that stretch of water from the Fastnet light to the south

point of Wales, was rough to say the least. I recall the boat dipping

under the green swells till the whole deck was awash, then coming up

again like a whale till the next sea hit us. The approach to Milford

Haven was dangerous at the best of times. In darkness and bad weather,

and without the benefit of radar or electronic position fixing, it was a

salutary experience for a 15 year old boy, taking the boat around the

dangerous and exposed ‘Smalls’ rocks before the entrance to the bay and

the sound.

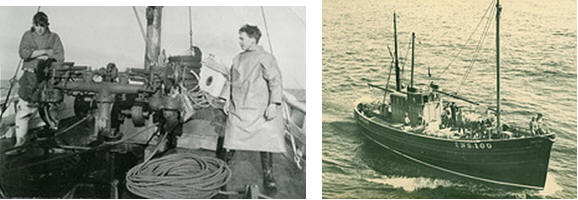

Loading up with fish in the days of

plenty

Myself attending the

winch with Sean Cotter My father’s vessel, MFV

Kincora

The year in Ireland was memorable, though not without its

sorrows. I had lost my paternal grandmother and an uncle the previous

summer. Then we got word that another uncle had been lost at sea off

the north of Scotland. His body was never recovered. Altogether I lost

three uncles and a cousin at sea, and many, many friends. One of the

first boys I befriended in the Killybegs fleet, ‘Benny’, was lost the

following year off Dunmore East. My other Killybegs chum, Anthony, was

washed overboard two years later. Strangely, despite the considerable

loss of life, we did not think much of the danger, any more than I

suppose miners did of their profession. It was just one of the risks of

the job. My home port lost its share of vessels over the years. During

my lifetime, boats that were sunk or wrecked included the

Resplendent, Caronia, Devotion, Trust, Palm, Briar Rose, Strathyre,

Scotia, Polaris, Incentive, Balmoral, Guide On, Arcadia, Renown,

Valkyrie, Sapphire, Ben Aigan, Argosy, Balmoral (2), Premier, Valkyrie

(2), to name but some. At least three of those losses

involved the whole crew, and 4 crewmen were lost in another. Several

individual deaths at sea also happened over the same period. Our small

harbour probably lost more than 20 boats and over 30 men in a period of

around 40 years. Throughout the north of Scotland overall, there has

been a horrific loss of boats and men year after year. Scarcely a

winter passes without another major fishing vessel tragedy occurring.

A bag of herring taken off Dunmore East

Having been at sea in

times of bad weather, severe gales, and storm force winds, I am

sometimes asked about the element of fear. The truth is, it rarely is a

factor. For me, the exception would be when sailing close to rocks or

reefs in strong tides, heavy swells, or poor visibility from rain, snow,

fog, or darkness. Then, one has every reason to be extremely alert, and

a natural fear is a healthy step in that direction. But to observe a

storm at sea, from a reasonably stout vessel, however small, is an

aesthetic experience rather like climbing a steep mountain, I guess.

One feels something like an inner thrill, - strong feelings of awe, and

wonder, and amazement. This is precisely what was said by that

amazingly tough, courageous and intrepid lassie, Ellen MacArthur, of her

single-handed sail voyage around the world, and her encounter with the

storms south of Cape Horn. “This is nature!”, she exclaimed.

“This is the sea, in all its power and grandeur”! And I cannot but

agree with her, though the storms I knew were much inferior to what she

endured. Over the years, I have witnessed the many moods of our seas

and oceans, from the calm, but occasionally turbulent tropics, to the

northern and southern latitudes with their breezes and active weather

patterns, to the Arctic waters, sometimes frozen over, or carrying huge

icebergs. The sea reflects our global climate and environment, perhaps

better than any land mass or vegetation. It can be incredibly

beautiful, remarkably pristine, and it can be dark and foreboding, or

wild and untamed. Yet it is the source and sustainer of most of earth’s

life forms, and without its benign influence, our planet would die. The

primeval poem of Moses in the Book of Genesis, tells us that all life on

earth began when, “Darkness was upon the face of the deep, and the

Spirit of God moved across (or hovered over) the face of the waters; and

God said, ‘Let there be light’.”.

The remarkable lone yachtswoman, Ellen

MacArthur

In May 1956 we decided

to return to Scotland and join the home fleet which was enjoying good

fishing and reasonable prices. The trip home was unforgettable. We

sailed north past Tory Island on a day that was as pleasant and calm as

it had been rough on my first voyage around that coast. Huge basking

sharks were lazily taking their fill of plankton, and I had fun trying

to sail over them which we occasionally did, but without any damage

whatsoever to those large but harmless monsters. We sailed through the

Caledonian Canal in one day, which you could do in the summertime then

provided you started at the first of daylight, and worked hard at

opening and closing the sluices speedily. Today the locks and sluices

are electrically operated, but bureaucratic rules limit the times of

their operation. Yet the canal remains a great benefit to fishing boats

and yachts, and a tribute to its builder, the Scottish engineer Thomas

Telford, who designed the waterway and cut the channels adjoining the

lochs, and built the “Neptune’s staircase” of locks that lift and drop

the boats from sea level to the highest lochs on the route through the

Great Glen.

|

Two

‘Peters’ who wrote of Scottish Fishers

Peter F

Anson, an Admiral’s son from Portsmouth, was a Benedictine monk

for 11 years, yet had a life-long interest in and love for

fishermen, fishing boats, and fishing communities, and founded

the Apostleship of the Sea in 1921. A gifted writer and artist,

he set up the Society of Marine Artists. He wrote and

illustrated 35 books, and was made a knight of the order of St

Gregory in recognition of his marine work. His books cover

marine art, the church and sailors, and harbours, boats, and

fishermen from Brittany to the Shetland Isles. But it was

Scotland’s fisheries that absorbed most of his attention, and

for most of his working life he lived on the Moray Firth coast.

His drawings of sailboats, steam drifters and the early motor

fishing vessels, are now a classic historical record, as are his

descriptions of life on the fishing boats and in the coastal

communities. Among his best known publications are:

Fishermen and Fishing Ways; Scots Fisherfolk; and Fishing

Boats and Fisher Folk on the East Coast of Scotland.

Comments

made by Peter Anson in 1971 (at the age of 82), have a strangely

prophetic relevance to what we face today: “I described what

is now a vanished world, for the fishing industry on the east

coast of Scotland, and everything connected with it, have

undergone tremendous changes. Fisheries are now concentrated in

(a few) major ports; the numbers of fishermen and vessels have

dropped to half what they were 40 years ago; and many of the

harbours are now empty, except for a few small yachts, and

haunted by the ghosts of long-dead fishermen. Nevertheless,

(Scottish) fishermen have preserved those qualities of sturdy

independence and shrewdness which enable them to fight against

the forces of nature as well as London bureaucracy, always

trying to tie them up with ‘red tape’.”

Peter

Buchan – “Oxo” to his friends, - was a fisherman from Peterhead

who served on line boats, steam drifters, and seine net boats,

the family ones named Twinkling Star, and Sparkling

Star. He possessed a natural gift for poetry which he wrote

mostly in the ‘Doric’ tongue, the dialect of the Aberdeen /

Buchan area. Peter Buchan is to the fishing communities of

north-east Scotland, what Charles Murray of “Hamewith”

fame is to the farming towns of the same region. I was

privileged to be involved in the publication of some of his

poetical works which were published under the title “Mount

Pleasant” after a location where he spent many happy boyhood

days.

Among his

best loved poems are; The Mennin’ Laft; Not to the Swift;

Best o’ the Bunch; Home Thoughts at the Haisboro’; The Skipper’s

Wife; and Buchan Beauty. Peter also wrote some

couthy stories, and contributed to local publications on the

Doric dialect. It is very difficult to select a few lines from

Peter’s work, since each poem has merit. But here are four

verses from Home Thoughts that describe the close of the

annual herring fishery off Yarmouth and Lowestoft in the late

autumn of the years from 1890 to 1930. For the sake of

non-Aberdeenshire people, this poem is in English !

November’s moon has waned; the

sea is dreary,

December’s greyness fills the

lowering sky;

But we are homeward bound, our

hearts are cheery

For far astern the Ridge and

Cockle lie.

The silver harvest of the

knoll’s been gathered;

The teeming millions from

their haunts have flown,

From Ship to South-Ower Buoy,

the sea’s deserted,

And we have reaped whereof we

had not sown.

When snow lies deep, in cosy

loft a-mending

Our nets, the times of danger

we’ll recall,

The days of joy, the nights of

disappointment,

Each silver shimmer and each

weary haul.

And children, sitting

chin-in-hand, will listen –

Forsaking for the moment,

every toy;

For there’s a deep and wondrous

fascination

In sea tales, for the heart

of every boy.

|

Fishing at home proved

to be somewhat harder than in Ireland. We went farther afield to find

fish, and often worked night and day without stopping. The longest I

stayed on my feet in one stretch was two days and two nights, but even

when we got some rest more often than not it amounted to only four hours

per working day. One learned to snatch sleep at every opportunity, even

in the galley with our oilskins on while awaiting the call to shoot the

gear. I was in charge of the ropes and the winch, which meant that I

had to be the first on deck when operations began. That first ice-cold

lash of salt spray across the eyes before daylight on a winter’s

morning, is something I will recall as long as I live, and the

recollection makes me grateful for a dry clean bed and 6 or 7 hours

undisturbed sleep each night. After I left the sea, more modern vessels

were constructed with whalebacks or with wholly enclosed shelter-decks,

but in my time deckhands were fully exposed to the elements. Strangely,

the improvements have not seemed to result in any reduction in the loss

of lives or of fishing vessels in the North Sea.

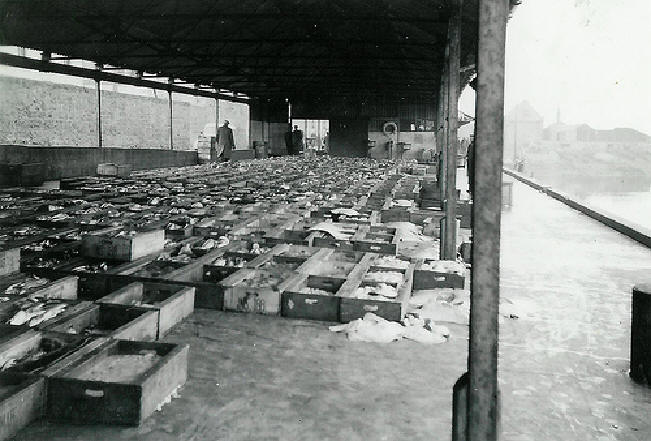

Our fish market in the days

before the EU CFP depleted our fleet and restricted our access to fish

stocks

Seine-net boats

supplied local fresh fish markets, and their trips rarely lasted more

than 5 days. Some boats landed their catches daily. This contrasted

with the distant water trawlers from Hull and Grimsby in England,

fishing off Iceland and Spitzbergen, that were at sea for up to 21

days. It is surprising to think now that their cod catches stored in

ice could stay fresh that long. Other trawler fleets operating from

Aberdeen, Granton (Leith), Fleetwood and Milford Haven fished mainly off

Rockall, St. Kilda and the Faeroe Isles, and would limit their trips to

14 days. The distant water trawlers packed their fish in bulk, in ice,

in compartments in the fish hold which were separated by pound boards or

duck boards. The seine net vessels placed all their fish neatly in

wooden fish boxes that held 7 stones of fish plus ice. This made the

fish more presentable on the fresh fish markets.

Myself on deck, approaching the harbour

on a fine summers day.

We operated in waters

varying from a depth of ten fathoms (60 feet) to 120 fathoms. By

present standards that would be considered shallow. Today only prawn

trawlers would bother to tow their nets in 10 fathoms of water, and few

white fish boats would do so in less than 30 fathoms. Our modern deep

water vessels now fish on the sea bed as much as 700 fathoms below

(4,200 feet). This is for deep water species such as blue ling,

grenadier, orange roughy, rat-tail (or rabbit fish), siki dogfish and

black scabbard. In our day we thought we were exploring the deep when

working grounds of 100 to 120 fathoms, such as the “skate hole” off

Fraserburgh, or the “Noup deep” off the northwest coast of the Orkneys.

On such trips in the summertime, we would stay at sea for five days and

return with a mixed catch of different types of skate and ray, witches,

megrims, monkfish, dogfish, halibut, cod, haddock, saithe and hake.

Our regular fishing

grounds were the banks of the Moray Firth, North Scotland, Hebrides,

Minch, Dubh Artach and the Clyde. On soft bottom grounds you would tend

to get a predominance of whiting, especially off the west coast. On

the harder gravel or shingle you found mainly haddock, and some cod

during their spawning season. Plaice were a shallow water fish, and the

more valuable species, brill, turbot, wolf-fish and lemon sole, would be

found on harder bottom, or close to rocky ground. My father preferred

to go after quality fish and was for ever setting his net close to rough

sea bed. In consequence, the gear often snagged, and sometimes got very

badly torn. Dover sole, or black sole were a much prized species, and

we caught them mostly on sandy and muddy bottom in the Irish Sea and on

the south and west Irish grounds. Powerful Dutch beam trawlers were

later to concentrate on this species with considerable success.

Haddocks caught off the Orkney Islands

When fishing for haddock, which we did for most of the year,

there was not much by-catch. The same was true of the whiting

fisheries. Large haddock, like large cod, were easy to handle, and a

crew could gut them in relatively short time. Small haddock, or small

whiting, were a different story. There could be 150 to 250 fish to a

box, and so 100 boxes would contain 15,000 to 25,000 fish. Whiting have

small sharp teeth, and ones hands would be ‘ripped to shreds’ gutting a

large number. An average deck crew of five men would have to gut 3,000

to 5,000 fish each when handling 100 boxes, not to mention the washing,

packing and icing, and the setting and hauling of the gear. Small

whiting and small haddock fetched minimum prices most of the time, and

could be sold for fish meal in the warmer months, which was galling

after so much work. So our crew was glad that the skipper generally

targeted the larger more valuable fish, even though that meant more

repair of torn nets at times.

Above : The Old Man of Hoy, the

towering rock off the entrance to Hoy Sound

We worked most of the

year on ‘Stormy Bank’ which lies to the west of the Orkneys and

near the Sule Skerry lighthouse. The prime catch there was large

haddock and my father was adept at finding and catching them. We landed

our catches mostly at Scrabster, just west of John O’Groats, except for

the last two days fish which we would carry to our home port. We spent

some stormy evenings in Scrabster, and one wild, snowy December night,

were called out to pull an Aberdeen steam trawler off the rocks under

Holburn Head light. If as often happened, we had to remain there for a

week-end (our boats never fished on Sunday), then we would be royally

entertained at the local Fishermen’s Mission by the junior Salvation

Army Band and songsters from Thurso. Our fish salesman there was a fine

man of considerable integrity, and a leading member of the local

Salvation Army. John Sinclair, was also Lord Lieutenant of Caithness,

and a respected friend of the Queen Mother whose Castle of May was

located nearby. One of the superintendants of the Scrabster fishermen’s

mission later married the young Salvationist who led the songsters. I

caught up with them again many years after, in charge of a

Congregational church in Alloa. They were as bright and as enthusiastic

as ever.

When fishing closer to

the Orkneys we enjoyed occasional spells in Stromness harbour. We would

enter Hoy Sound from the west, past the tall and imposing “Old Man of

Hoy”, the huge pillar rock in the shape of a man standing face to the

sea, and once inside turn north into Stromness harbour while the famous

former naval base of Scapa Flow lay open to the south. The Orkney

people were wonderfully hospitable, and it was a treat to be

weather-bound there or to spend a week-end with that happy community.

The womenfolk were expert bakers, producing a marvelous range of scones,

pancakes and shortbreads. It was in Orkney that my path first crossed

that of the great Captain Cook. He had charted the seas around the

islands, and a plaque at the west side of the town marked where his ship

had collected fresh water. I was later to use charts in Newfoundland

that were based on Cook’s survey work in Canada. And in the Pacific, I

traveled to many of the islands he visited on his epic voyages of

discovery.

There was little time

for activities other than work or sleep on a fishing boat, except when

weather bound in a harbour, or at anchor. Books were read at all spare

moments, and the radio provided both news and entertainment.

Occasionally a musical instrument would be played, usually a mouth-organ

or squeeze-box (melodian). My father was adept at both. Playing cards

were sometimes produced. Generally they were not regarded as a wise

pastime, though ‘cribbage’ was popular with the older men. Draughts was

the great board game in the cabin. Matches would be observed intently

by all the crew as if the contestants were top chess players. Another

game that suited the smooth cabin table with its half-inch lip of wood

to keep plates and cutlery in place, was “penny-ha’p’ny football”. It

was usually played with two pennies and a sixpenny bit but any sized

coins could be used.

The Kincora in the Firth of Clyde,

1960

In Caxton Hall, London, 1958 I am second

from the left. Admiral Sir William Agnew is in the chair.

In 1958 I was given a

surprise honour in being invited to be the fisherman speaker at the

annual meeting of the Royal National Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen,

which was then held in Caxton Hall in London. I had rejected the

invitation at first as there were many fishers much more mature and more

deserving of the opportunity, but the organization insisted and I

reluctantly agreed. It was only a ten-minute slot in a fairly long

programme, but my contribution was appreciated by all including the

senior committee member Admiral Agnew [Sir

William Gladstone Agnew, Vice-Admiral, who commanded HMS Vanguard during

the royal tour of South Africa. He gave valuable and unstinting

support to the Fishermen’s Mission during his retirement.] who led the applause with a loud “Bravo!”.

The long established mission was still then undertaking extensive social

and spiritual work in the country’s major fishery ports. The RNDSF had

begun in the 19th century when it served Dogger Bank fishers

from a mission ship stationed at sea. The great Dr William Grenfell of

Labrador fame, served as a Fishermen’s Mission worker before moving

across the Atlantic.

A particular treat for us in the fishing year, was the annual

cod fishery in the Firth of Clyde. The cod used to arrive there in

February to spawn, and would be plentiful until the end of April. We

liked the Clyde fishery because there was almost no night-time fishing,

and the grounds were rarely more than a two-and-a-half hour steam from

port, whether Ayr, Girvan or Campbeltown. Campbeltown Bay lay inside of

Davaar island which you could walk to at low water. Inside a cave on

the island was an amazing rock painting of Christ on the cross that has

had a deep impression on many visitors. In the 1950’s west highland

“puffers”, - small, tubby steam-powered cargo boats, still carried coal

and other cargo to and from the small coastal and island ports. The

quaint, romantic puffers were made famous by Neil Munro in his “Para

Handy” tales. We often lay beside puffers at night in Campbeltown,

and occasionally exchanged a fry of fish for a basket of coal.

Dubh Artach lighthouse off the island of

Mull, SW Scotland. Right : UK 1981 postage stamp of seine net fishing

based on a Kincora photo. The artist Brian Saunders added the wheelhouse

front from a photo of the seiner Success KY 211 in Gloria Wilson’s

book. Thanks to reader John Spink for pointing that out.

When in Ayr or Girvan

harbour, our cook would stock up with “Land o’ Burns” bakery

bread which I then considered the tastiest in all Scotland. (One of my

esteemed colleagues I was to meet later, Roger Mullin, was a son of one

of the company’s master bakers). The Ailsa Craig, “Paddy’s Milestone”,

dominates the Firth, and we fished on every side of that enormous rock

with its huge colonies of gannets. One of my father’s boats was sunk to

the south of the Craig. It happened in March 1948.

The “Resplendent,

INS 199”, a 60 foot seine netter, had sailed from Campbeltown

and reached the fishing area before dawn in the middle of a light

blizzard. My father was “dodging” as we say, - keeping the boat’s head

to wind, while he waited for the weather to clear. Another fishing boat

approached, and my father wondered if it wanted to pass a message, (not

all boats had radio-telephone then). But the other skipper had taken a

momentary black-out and his vessel ran straight into my father’s boat

which was holed under the port light and sunk in minutes. All of the

crew survived though one was injured. My father was the last to be

picked up. He had lost consciousness in the water but had grabbed a

rope that was flung to him. On the rescuing vessel they could not

prise his

unconscious hands from the rope. It was one of three shipwrecks that my

father

survived.

The news of the sinking

was broadcast on BBC radio that morning before my mother had been

informed. I had called at a friend’s house on the way to school and was

asked rather nervously about it by his parents. I responded with

remarkable confidence that it must have been another boat of the same

name. Other chums at school approached me to see if my father was

safe. I had no idea, but, accepting by then that the boat had sunk, I

told them with similar assurance that all the crew had gotten off

safely. This was the case, though my father was at that time still

unconscious in Campbeltown hospital. My mother who had not heard the

radio reports was eventually given the news by lunchtime that day.

Recently I made a

nostalgic trip to Ayr of which I have many pleasant memories from the

cod fishing days. We used to visit the home of the Head of the fire

station, John Cooper, an extremely fine man. One of his employees then

was a young Jim Sillars, the future Member of Parliament for Ayrshire

South and Glasgow Govan. John and his lovely wife May were the soul of

hospitality. He was the epitome of the “honest men” of Ayr, and

she of the “bonnie lassies”. [From

the poem “Tam O’ Shanter”, by Robert Burns.] I would fillet fish for them each week, and for Tom and Ina Martin who

ran a colporteur’s van and shop, as well as the Watson’s, a mining

family in New Cumnock. Anyhow, when I wandered recently down to the

former pier and fish market near the mouth of Ayr river, I was surprised

to see that all trace of the fishing activities had gone. The pier that

once thronged with merchants and boxes of fish landed from seiners,

ringers and trawlers, was strangely clean and quiet. The area had been

totally re-developed with large blocks of modern flats. It left one

with a strange feeling that a world one knew had been lost. I was

reminded of how the old Authorised Version put it, “As for man, his

days are as grass; as a flower of the field, so he flourisheth. For the

wind passeth over it and it is gone, and the place thereof shall know it

no more”.

What happened to Ayr

has happened to fishing ports all around Britain. Britain’s surrender of

its 200 mile fishing zone to Europe, and the rigorous application of the

EC common fisheries policy, has ensured the demise of our once great

fishing fleets, and the industry that thrived for 500 years. Scotland

used to have over 40 thriving fish market ports. Today there are less

than ten of any consequence. It has taken Europe only 30 years to

destroy the once great industry that Scots fishers spent over 3

centuries developing. People’s jobs and community’s future livelihoods,

have been traded on the market place in the form of “Individual

Transferable Quotas”. ITQs were supposed to result in economic

efficiency, but they do not produce a single extra fish, only widespread

social injustice and deprivation. In every place where they have become

a major weapon of government fishery policy, - like in Canada, New

Zealand, and the EU states, they have been a means of legal thievery,

allowing those with money and influence to steal the harvesting rights

of fishers and fishing communities, - rights that their fore-fathers

toiled and invested, and risked their lives for generations to secure.

The most iniquitous

consequence of that callous policy, I have personal knowledge of, from

the hundreds of hard-working, law-abiding individuals and families who

have lost their livelihoods, life earnings, and sometimes homes as

well. And also from the many once thriving coastal communities from the

Hebrides to the Moray Firth, that now lie stagnant and bereft of any

economic future, save what will come in the form of hand-outs from the

Brussels and London regimes that robbed them of access to their

resources in the first place. Once thriving, self-supporting

communities are now economic graveyards.

One might put it all

down to sheer incompetence or bureaucratic stupidity and pig-headedness,

but I suspect worse. Behind all of the irrationality and lies and

manipulation and deceit by politicians and civil servants in Edinburgh

and London, and Brussels, one senses the hidden hand of a right-wing

agenda that sees control over resources and profits in fewer and fewer

hands, as being economically efficient and justified by some unspoken

monetarist philosophy.

More fish, - but this market has been

empty now for over ten years.

|

The Demise

of the Scottish and English Fishing Fleets

Our

fishing heritage pre-dates Columbus. He sailed on English line

fishing sailboats to Jan Mayen Island in his preparations for

the Atlantic crossing. Those vessels had live-wells built into

the hulls to enable them bring cod and halibut back alive from

the long voyages. Other fish were split and salted, and some

boats even carried ice harvested in winter from the marsh-lands

in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. Herring fleets were built to

compete with the Dutch who had pioneered drift net fishing in

the 17th century. By the 18th and 19th

century, fleets from Bristol were fishing off Newfoundland for

cod. The British navy regularly burned down settlers camps in

Newfoundland at the end of each year, to prevent the development

of an indigenous new world fleet that might compete with the

English merchants.

The

development of steam power, and the otter trawl led to the

growth of the distant water fleets of Hull and Grimsby. These

ships fished as far north as Spitzbergen, and as far west as

Greenland. Fleets from Aberdeen and Fleetwood operated off

Iceland and the Faeroe Isles. Diesel and diesel-electric power

led to the development of the stern trawler, the

freezer-trawler, and the factory trawler. A British company of

Scandinavian origin, Salveson’s built the first two factory

trawlers in the world, the Fairtry 1 & 2. These models

were quickly copied by the USSR which built hundreds of similar

factory ships.

By 1970,

the fishing industries of England and Scotland were among the

finest in the world, in technology, efficiency, and quality of

produce. Britain was producing over a million tons of fish a

year, and with the advent of the new UN Law of the Sea, was

preparing to claim its international right to the resources of a

200 mile Exclusive Economic Zone around the British Isles.

However,

in 1970, a rise in white fish prices and a resurgence in herring

fishing was boosting the prosperity of fishermen and fishing

ports. The country’s fishery future looked secure. Then came

Britain’s entry into the then European Common Market in 1973,

negotiated by Edward Heath.

Hours

before Britain was to be admitted, the original six members

drafted the notorious addition to the “Acquis Communautaire” (that applicant states had to accept in entirety). It

obliged new members to surrender the control of their waters to

Europe, and to agree to “equal access to a common resource”

as far as fish was concerned. All new applicants for

membership would have to accept the condition, and that has been

the case since. Despite a stream of subsequent lies and

deception that this was not really the case, the government had

sold the fishing industry like a pawn to gain entry to Europe.

The European Commission then assumed the authority to delegate

shares of the fishery resource to member states.

Astonishingly, apart from Ireland, and the European maritime

states that had nothing to lose and everything to gain, Britain

was the only nation in the world to give up that sovereign right

to its exclusive fishing zone, and accept the principle of

‘equal access to a common resource’ which was made a condition

for all EC members.

Year’s

later, Spain’s full entry into the EU CFP nearly doubled the

size of the EU states fishing fleets, and the later entry of the

Baltic states brought more fishing effort. The English and

Scottish fleets had to be seriously reduced in size to

accommodate the others.

What it

had taken British seamen and merchants 500 years to develop, was

systematically reduced and destroyed by the EU Common Fisheries

Policy in the 30 years from 1975 when measures started to be

applied. No other nation in the history of the world has given

up its fishing industry to foreign interests as has Britain. No

state outside the EU has surrendered its 200 mile EEZ fishing

zone to another body. Today, the vessels that reap the benefits

of the UK marine EEZ are fleets from Spain, France, Denmark,

Holland, and the new EU member states of Poland, Latvia,

Lithuania and Estonia. In consequence, much of the fish

purchased by British housewives, though caught in British

waters, are from Continental fishing vessels.

I was

later to describe the destructive impact of the European Common

Fisheries Policy on our fishing fleets and fishing communities,

in a number of publications. Following the Kyoto Conference of

1995, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation

commissioned a number of studies of vulnerable coastal

communities. The studies were financed by the Japanese

government. I was honoured to be asked to undertake the

European study that was to focus on the Hebrides and the west

coast of Scotland. This study was included in the FAO

publication TP 401, A Key to Fisheries Management and Food

Security. On the basis of that study, I then produced a

book entitled The Sea Clearances which was published in

2003. I was also asked to give a lecture on the subject at

Edinburgh University and other institutes.

However,

despite these publications, and numerous letters to the national

press, and submissions to the Westminster Parliament, the House

of Lords, and the Scottish Parliament, our government refused to

budge on its attitude to our fishing industry which they viewed

as small beer, and a pawn well worth sacrificing for other

benefits they imagined the European Union would bring. |

One

of the fleet of beautiful seine netters which once operated from our

home port. None of these vessels remain. Most were forcibly

decommissioned.

If I was to make a

serious career of the fishing, I had to acquire relevant qualifications,

so I attended some navigation classes led by our town Provost and

excellent mathematician, Roy Tulloch. That enabled me to pass the

examinations for Second Hand (Fishing mate). Two years later I went to

Aberdeen to study for my Skipper’s papers at Robert Gordon’s Technical

College (now a University).

Among the other fishing

students then were Terry Taylor who became one of Aberdeen’s top distant

water trawler skippers, Willie Cowie of Buckie who also did well on his

boat the Strathpeffer, and a really fine young man from Mallaig

on the west coast, Zander Manson who was to become a top herring

fisherman. Sadly, Zander lost his life when his boat the Silvery Sea

was run down by a cargo vessel just off the coast of Denmark in 1995

with the loss of all on board. But mercifully those future

events were hid from us then.

Certificates of

Competency for Fishing Skippers involved examination in the 32 articles

of the ‘Rule of the Road’ as we called the International Regulations for

Prevention of Collisions at Sea. The character, colour, height and

horizontal range of all ships’ navigational lights, had to be stated

with precision. One had to recognize by models or illustrations of

lights, the type of vessel represented, whether it was under way or at

anchor or being towed, and say within a given arc of the compass, the

direction in which it was heading. Fog signals had also to be

recognised. Eye tests had to be conducted first to ensure candidates

had colour vision. There followed a number of navigational papers on

determining position by sextant observations of stars and of the sun at

its meridian. Chartwork took up a morning or afternoon, and there was

an oral exam at which one could be asked any question the examiner

considered relevant. Among the questions candidates expected were the

local lighthouse flashing sequences, fog signals of various specialist

ships, legal obligations of masters, and actions to be taken in

emergency situations. One had to demonstrate ability to read and send

morse code, use semaphore flags, know the main code flag signals, handle

a sextant, and operate pieces of equipment like a radio direction

finder. (Today it is the use of radar and satellite navigation

instruments that predominates).

Along with the other

candidates, I duly sat and passed the three-and-a-half days of

examinations, (my certificate being the ‘full’ one that covered any size

of fishing vessel, anywhere in the world, - now termed class 1 fishing

captain). Having acquired the necessary qualification, I was then ready

to take on appropriate responsibility.

But events had

overtaken me. It was the family’s intention to assist me to obtain a

vessel which I would command. Practically all the boats in our fleet

were family owned, with brothers, uncles, cousins, holding shares of a

quarter, an eighth, or even a sixteenth. Financing such a venture was

made easy by a generous Government grant and loan scheme. We had gone

as far as getting plans and quotations for a 72 foot 200 hp seine netter

from boatyards in Buckie and Fraserburgh. The Head of Gardner’s had

promised us the first of a new range of their marvelous marine workhorse

engines. I had compiled a set of fishing charts, a record of annual

fishing activities, and Decca navigator readings of the position of

particular fishing grounds.

But that year, the

North Sea and Moray Firth were replete with small haddock which swamped

the market and brought prices down. Fish that failed to fetch the

minimum price for human consumption were withdrawn from auction and sent

‘up the road’ to the fish meal plant for about ten shillings per 7-stone

box. (That would be just over a penny per kilo in today’s money). My

senior uncle counseled waiting till prospects improved before taking on

the burden of repaying a new boat, then costing around ₤23,000. Because

interest on the money borrowed was heaviest in the first few years of a

new vessel’s operation, it was important to maximize earnings during

that initial period. So the venture was postponed. Needless to say I

was disappointed. But another door was about to open.

Far away in East

Africa, a huge dam had been constructed on the river Zambesi at the

Kariba gorge. This large undertaking was designed to provide electrical

power for the mines and townships of the ‘copperbelt area’ of Northern

Rhodesia. But it also had a political motivation, to cement the ties

that had created a Central African Federation out of the territories of

Northern and Southern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland. Today such dams are

being constructed with little thought for their environmental or social

impact. Despite the lack of such concerns 50 years ago, the Kariba dam

was to be beneficial from both points of view. The local tribes people

were to suffer, but that was for an initial period only.

The Batonga tribesmen

who lived along the river in the Gwembe valley, had to be moved upland

as the water rose to form a huge lake, 120 miles long, by 25 miles at

its widest points and nigh 400 feet at its deepest, then the largest

man-made lake in the world, extending from near the Victoria Falls to

the Kariba gorge. To compensate the tribesmen, a fund was established

to train and equip them to become fishers instead of farmers.

A Grimsby trawler

skipper was hired to go out and teach the people to fish. He was

planning to take his family with him, but changed his mind at the last

minute due to fears of social unrest in Northern Rhodesia as it

approached the transition to independence. The Colonial Office,

Department of Technical Cooperation, was contacted to find a replacement

fishery training officer quickly, this time preferably, a single man.

Word was sent from London to the White Fish Authority area offices in

the main fishing ports. The number of responses was modest. I was

approached by the local officer, somewhat casually, as he did not think

I would have any serious interest. But the opportunity had great

appeal, only I thought it unlikely they would take one so young and

inexperienced. The Member of Parliament for Banffshire, a fisherman’s

son himself, thought otherwise, and gave me a strong reference. I was

interviewed in London in April of 1962, and left for Northern Rhodesia

in August of that year. |