|

“When you enter

the land that I am giving you, let the land, too, keep a

Sabbath for the LORD. For six years you may sow your field, and

for six

years

prune your vineyard, gathering in their produce. But

during the seventh

year the land shall have a complete rest, a sabbath for the LORD,

when you

may neither sow your field nor prune your vineyard.

The

fiftieth year you shall make sacred by proclaiming liberty in the land

for all

its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you, when every one of

you shall return

to his own property, every one to his own family estate.

In

this fiftieth year, your year of jubilee, you shall not sow, nor shall

you reap

the after-growth or pick the grapes from the untrimmed vines. Since

this is the

jubilee, which shall be sacred for you, you may not eat of its

produce, except

as taken directly from the field. In this year of jubilee, then,

every one of you

shall return to his own property. Therefore, when you sell any land

to your

neighbor or buy any from him, do not deal unfairly.

Do

not deal unfairly, then; but stand in fear of your God. I, the LORD, am

your God. Observe my precepts and be careful to keep my

regulations, for

then you will dwell securely in the land.

The

land shall not be sold in perpetuity; for the land is mine, and you

are

but aliens who have become my tenants. Therefore, in every part of

the

country that you occupy, you must permit the land to be redeemed.”

from the

25th chapter of Leviticus

New American Bible translation

As soon

as the land of any country has all become private property, the

landlords, like all other men, love to reap where they never sowed, and

demand a rent even for its natural produce.

Adam

Smith,

The Wealth of Nations,

1776

All

right of property is founded either in occupancy or labour. The earth

having been given to mankind in common occupancy, each individual seems

to have by nature a right to possess and cultivate and equal share.

William Ogilvie of Pittensear,

The Right of Property in Land, 1782

To put

the bounty and health of our land, our only commonwealth, into the hands

of people who do not live on it and share its fate will always be an

error. Whatever determines the fortune of the land determines also the

fortune of the people.

Wendell

Berry, Conserving Forest Communities, 1995

I had

just returned from a series of assignments in Namibia where that small

country had reclaimed its fishing grounds from the European and South

African fleets that had exploited them to a state of severe depletion,

when I got a call from a young university researcher by the name of Andy

Wightman. I had written a few articles on national and local ownership

rights of marine waters, including one published in a national Sunday

newspaper, together with Roger Mullin. The success of the fledgling

African government and its local fishing industry, elicited a number of

complimentary responses from fishermen’s associations and those like

Wightman who were working on parallel issues of ownership and control of

land. Following a coffee meeting with Andy in the Royal Mile, I was

invited to submit a paper to an environmental journal, and later to

speak at an international conference on land reform and taxation. At

the international conference in Edinburgh University, I was struck by

the number of senior academics and researchers from other countries, who

saw the issues of land reform and taxation as lying at the root of much

of the inequality and injustice of current relevant laws and management

structures. It was particularly interesting to hear senior professors

from the USA, UK and Russia, in complete harmony on the issue. It was

at that conference I first obtained an in-depth glimpse of the works and

idea of Henry George.

Andy Wightman, writer, lecturer, and

tireless Scots advocate of land reform

Andy

Wightman went on to publish Who owns Scotland? and Scotland :

Land and Power, and to be a leading proponent and supporter of

Scotland’s limited act on land reform, Land Reform Scotland Act 2003.

The Act has guaranteed, 1) the right to roam, including wild camping and

canoeing, 2) the right of pre-emptive purchase at government valuation

by a community of rural land that is put up for sale, and, 3) in areas

traditionally governed by crofting tenure, the right of a community to

buy their land at valuation even when the laird has not placed it on the

market. An earlier 1976 act allowed individual crofters to buy their

patch freehold. That act forced individualism and so was shunned by many

indigenous tenants. The 2003 act in contrast, allows land to be bought

with tenancies over it to be held by the community.

There

are two powerful and privileged groups in most of the world’s societies

who increase their wealth day by day with scarcely any effort or

sacrifice on their part, save a tenacious defense of their property and

power. The two groups are those with legal title to land, and those who

own or control the major banks and financial institutions. The

constantly increasing value of their assets is based on the labour and

industry of the rest of society. Yet they continue to tax society at

increasing rates by the tools of rent and usury.

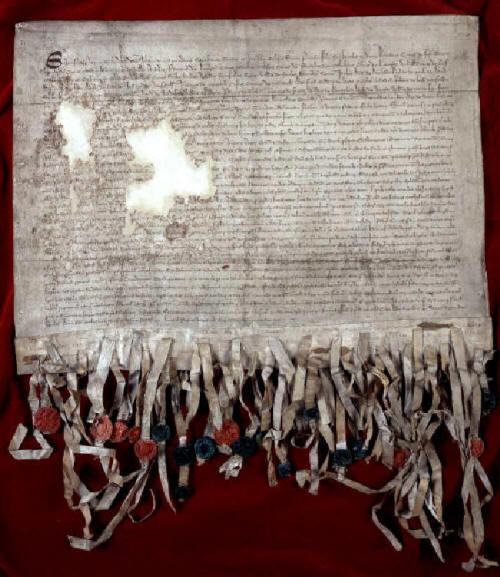

The

ownership and control of land is a concept that has come down to us from

medieval times, and become a foundation truth of capitalist society.

Yet a number of cultures and civilizations have regarded it as an alien

principle. Under the old Hebrew economy, land was ultimately God’s

property (Leviticus 25). The early Scots constitutional document, the

Declaration of Arbroath,1320, and subsequent legal statements,

declared that the land was held under God on behalf of the people. The

King or Guardian could not utilize lands in ways that offended the laws

of God, or were contrary to the interests of the people.

Copy of the Declaration of Arbroath,

Scotland’s oldest constitutional document

Illustration of feudalism

Many

peasant peoples have had a strong historical attachment to the land they

tilled or on which their animals grazed. Few such attachments were

stronger than those of the Hebridean and

West Highland Scots which made their eviction in the

century of the Clearances – 1750 – 1850, all the more cruel.

American Indians regarded land and nature as a sacred gift

of God, and could not conceive of it being sold or fenced off. To this

day, most of the countries of the South Pacific prohibit or limit the

sale of land and permit only its lease for a period. Most states in the

world prohibit the ownership of land by foreigners.

Similarly, the key role played by major banks and financial

institutions, in the control of global and national economies, began in

medieval times, and has developed to the point today where their

tentacles extend to the smallest and most remote pockets of economic

activity. Strangely the fiercest condemnation of excessive interest

charges is found in the Hebrew scriptures, and yet that people were to

dominate much of the banking world to present times. Islamic law also

prohibits the application of interest charges to

lending. Banks

make money out of nothing. Banking laws permit lending

far beyond the original financial deposits, and further

credit issue is maintained by a myriad of methods. Today,

small borrowers pay obscene rates of interest to the banks through the

numerous credit vehicles such as

credit cards, hire purchase schemes, overdraft facilities,

and direct

bank loans.

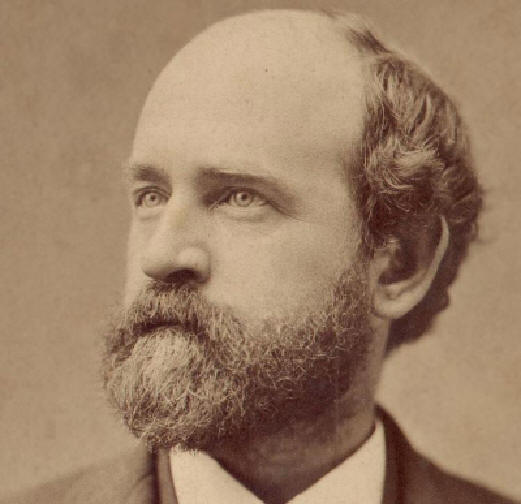

It fell

to a young American printer, a 7th grade school graduate, to

recognize the key roles of land ownership and taxation in protecting the

wealthy and powerful, and how they might be managed for the benefit of

all. Henry George, 1839 – 1897, was a ‘curious and attentive lad with a

strong mother wit’. He was also a voracious reader, devouring the works

of Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Hubert Spencer, and John Stuart Mill. His

first major book was Progress and Poverty, published in San

Francisco, and destined to be regarded as one of the classic works on

economics. Among its and George’s later admirers were notable figures

such as Leo Tolstoy, Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill, and John Dewey.

Henry George wrote of the “deplorable circumstances where in large

measure a very powerful few are in possession of the earth’s resources,

the land and its riches, and all the franchises and other privileges

that yield a return”.

Henry George, the proponent of a Land Tax

based economic system

He

asked, “Why should a man benefit merely from the act of ownership,

when he may render no services to the community in exchange ? What

gives the wealthy the right to become rich – not for service rendered to

the community, but from the good fortune to have advantageously situated

land?”.

His

solution to the inequalities produced by the economic system of 19th

century America, was a single tax, - a land tax, that would release the

value inherent in the nation’s land, to the benefit of the people as a

whole. He reckoned that a single tax would absorb all rents with no tax

whatsoever on wages or interest. A single tax would in effect lead to

ownership of land as common property. While his idea excited interest,

it did not lead to such action in its day, but now, over a century

later, there are numerous academics, economists, reformers, and students

of government, who believe that a land tax would indeed be a hugely

beneficial measure for any country.

In

Britain today, we cannot get a land ownership register, never mind a

land tax, so powerful are the vested interests that oppose any

encroachment on their privileged positions of profit and power.

Scotland is the most backward part of the country in terms of land

reform and land distribution. Nearly two-thirds of the country is owned

by around 1,000 persons. This situation is largely a relic from feudal

ages past and from the aftermath of the Jacobite rebellion when King

George granted huge swaths of the north-west of the country (the

highland estates) to those who sided with him and with the Hanovarian

cause. There is sufficient land in Scotland for every man, woman and

child to have 4 acres, yet when anyone wants a tiny plot on which to

build a small dwelling house, they have to pay anything from £20,000 to

£70,000 pounds or more. Why should a piece of unused land cost almost

as much as a house ?

A close

friend of mine, author of the book, Soil and Soul: People versus

corporate power, Alastair McIntosh, has been a powerful and

articulate voice for justice in our management of land resources, and

for respect for our historical and spiritual roots. His book is largely

about land reform and the community land trust of which he was a founder

on the Isle of Eigg. He noted that when Keith Schellenberg first bought

Eigg, in 1975, he paid £ 250,000 for it. When the island was sold on to

Marlin Maruma, two decades later, he got one-and-a-half million (though

it was less than he might have got had it not been for the

market-spoiling tactics of the Isle of Eigg Trust). By this time it no

longer conferred respect to claim to be “The Laird” in many parts of

Scotland. It had become thinkable to challenge the system whereby one

class of people live from the proceeds of a tax known as “rent” paid by

those who lack control over the place where they live.

McIntosh goes on to say that ‘rent, after all, is a tax from the

relatively poor to the relatively rich. Even the land component of our

mortgages can be traced back to such a transfer of wealth from poor to

rich. Land is not in short supply in rural Scotland. There is no earthly

reason why the building plot should typically cost as much as building

the house. After all, there are 5 million Scots and 20 million acres of

Scotland. That’s 3 football pitches each, which is not bad even if two

of them are on mountain sides. The central cause of the rural housing

shortage continues to be control over land ownership and a planning

system set in place when county councilors were typically lairdic types,

who valued the countryside not for the number of people whose lives it

could support in dignity, but as a playground for themselves and tied

housing for their servants.’

Island of

Eigg, Scotland Members of the Eigg Trust

Scotland’s west coast

Alastair believes that the 1976 crofter’s right to purchase the land he

works, did not sit well with the crofting communities or accord with

their views on rural communities, environmental sustainability, local

entrepreneurship, or affordable housing. He believes, under land

reform, crofting communities can be democratically accountable

landholders unto themselves, and that it is essential to block the

leakage of community assets onto speculative private markets. “This

can be achieved in various ways. Burdens on title deeds are one. Joint

ownership (or shared equity) is another, where the community retains a

controlling interest. And a third is to develop existing crofting

tenure so that communities retain inalienable control of the land upon

which private properties are built. Crofting matters for the future of

Scotland. It matters as a pattern of tenure by which people can live

with the land if not necessarily from the land. This generates a cycle

of belonging, identity, values, and therefore, responsibility that

sustains both people and place.”

Alastair McIntosh, writer, lecturer,

poet, and advocate of crofters’ rights

My own

view, which is mirrored in the land laws of some of the small island

states of the Pacific, is that there should be no private ownership of

land, but that all should be held by the state for the benefit of the

people. Land then may be leased, but not held in perpetuity by a single

family or corporation. In rural areas, communities could control local

land use and distribution in much the fashion as described by McIntosh.

These are my views and if ever put into practice, they would channel the

enormous income from increasing value of real estate, to the people who

live in the country, instead of to the banks and speculators as at

present. However, those powers are so entrenched in our society and its

legal and fiscal structures, that the chances of such reforming

legislation ever coming about, are close to zero!

Similar

land reform issues are being faced by the descendants of the once mighty

tribes of American Indians whose reservations today amount to just 4 %

of the land area of the USA. Winona LaDuke, a Muckwuck or Bear Clan,

Mississippi band, Anishinabeg Indian, struggled with the land issue for

many years, trying to win back or buy back, their reservation lands.

Her tribe, of which there are some 250,000 around today, is known as

Ojibways in Canada, or as Chippewas in the northern USA. Spanish

historians of the post-Columbus period have estimated that 50 million

American Indians perished in a sixty-year period. In addition to the

genocide, there followed cultural extinction that eliminated knowledge

and records of America’s indigenous peoples from most of the country’s

libraries and schools. White settlers believed they had a God-given

right to the continent, and that led to a denial of any rights for the

natives.

Access road through the White

Earth Reservation

Winona LaDuke, advocate of native

Indian’s rights

The

White Earth Reservation of Winona’s people was created by treaty in

1867. In 1887 a General Allotment Act was passed to teach Indians the

concept of private property and to facilitate the removal of more lands

from that nation. The reservation land was divided into 80 acre parcels

and distributed among the Indians with scant regard to the ecosystem or

to traditional land tenure patterns. After the land parcels were

allocated, the “surplus” land was given to white homesteaders. The

federal government then began to tax the Indians for their ‘allocated’

lands, and when they were unable to pay the taxes, the land was

confiscated. Speculators also came and cheated illiterate Indians out

of their reduced land-holdings. The sad story is a tale of land

speculation, greed, and unconscionable contracts. The White Earth

Reservation lost 250,000 acres to the State of Minnesota. Throughout

America, reservations lost on average a full two-thirds of their land

this way.

The

LaDuke project, if we can term it that, seeks to restore land to Indian

ownership and utilization on the lines of the traditional economy. It

also addresses the issue of absentee landlords, and works to restore and

strengthen cultural values and practices. Through numerous legal

battles they attempt to redress the Federal Government’s failure to

honour treaty obligations, and to reverse past decisions that were

clearly illegal. Winona believes that the term ‘sustainable

development’ is a misnomer. She says that it is communities that are

sustainable, not development per se. But proper use of land is at the

centre of the project. Her tribes are entering into a co-management

agreement with northern Wisconsin and northern Minnesota to prevent

further environmental degradation of the region.

The

pattern of ‘colonial’ expropriation of land from indigenous peoples has

been repeated all over the world. In South Africa we had the shameful

Apartheid policy that forced people into miserable townships from

where they had to serve the labour needs of the mining industry or of

the affluent suburban whites. In Kenya, Lord Delamere told a Native

Labour Commission of 1912-13: "If ... every native is to be a landholder

of a sufficient area on which to establish himself then the question of

obtaining a satisfactory labour supply will never be settled."

During

my years in the Philippines, I saw the social inequities, environmental

damage, rape of resources, and exploitation of the rural poor, that all

result from ownership and control of land by a privileged few. The

situation continues all over the country, but especially in Negros, and

the Visayan islands, and in huge parts of Luzon. It is the leading

factor contributing to the nation’s four main ills : wealth and

political power in the hands of a small elite; an over-powerful army

that treats rural peasants with callous brutality; NPA and Mindoro

(extreme Moslem) led terrorist reprisals; and blatant corruption

throughout the government and its institutions or organs.

What

has and continues to happen in the Philippines, is going on throughout

Latin America, Africa, South Asia, and Indo-China, to varying degrees.

Rural peoples who had traditional ownership or user-rights to their

lands, are having these disregarded or overthrown by legal thievery or

the power of the market in a situation of escalating land values. Poor

families are being pitted against powerful property developers. The

basic problem to me is the privatisation of land. When it is a saleable

commodity, (as with fish quotas or fishing rights) it leads to a trade

in people’s jobs and communities’ futures.

Land

ownership and land tenure are extremely sensitive and contentious issues

in the Pacific states and small island countries of the Indian Ocean and

the Caribbean. Over 90 % of land in the Pacific islands is customary

land, - held by individuals or families under traditional or legally

recognized customs. Land may not be bought or sold, especially to

foreigners, except under arrangements that are strictly controlled.

This can be frustrating to colonial powers or investors from abroad, who

continually badger governments for more flexibility, - fortunately, with

little success in most cases. But land can be leased for a period to a

foreign company, or to a local joint-venture company with oreign

partners.

Perhaps

no other issue is more delicate, or discussed more often by the Pacific

states and international bodies like the World Bank, and the Asian

Development Bank. These institutions, accustomed to globalization and

to western capitalism, are not normally sympathetic to traditional

practices when they conflict with modern business attitudes, - but they

have come to recognize that in those island societies, land has deep

cultural, tribal, historical, and even religious significance for the

people, and outsiders meddle in the arrangements at their peril.

Australian governments tried to impose their laws on land ownership or

title to Papua New Guinea, but failed, and probably caused some damage

in the attempt.

As

expressed elsewhere, I personally believe that all land should be kept

under national control, and all income from escalating land values

should be shared between the people and government, and used to assist

young couples to obtain their first home, or to help small or emerging

businesses with locations for their establishment. At present it is

mostly banks and speculators who benefit.

|

Changing land values in Cambodia

The lovely people of Cambodia went through such horrors during

the period of the Khmer Rouge regime, are now somehow putting

the past behind them and building a productive and sustainable

future for themselves and their children. Among the many

threats they face is land-grabbing which is increasing at an

alarming rate.

Rural villages in Cambodia’s Tonle Sap basin

The land-grabbing is fuelled by escalating prices to meet the

demand for commerce and tourism, and housing for the wealthy.

Individuals and families that acquired a few hectares of land

ten years ago, have become millionaires as a result. This has

tempted thousands of others to engage in land speculation.

Small farming communities where cash income is as low as one

dollar a day, can be sorely tempted to sell out to these

opportunists. Where they do not sell, the would-be buyers can

get around that obstacle by bribing local officials and

individual community members to connive in legalising an

improper purchase. But if the buyer is very rich, or a senior

military officer, or a high-ranking government person, then even

the legal niceties can be disregarded.

Take a community that has lived for generations in the Tonle Sap

region (which the United Nations has declared a biosphere to be

protected), and which engages in simple sustainable agriculture,

fishing or forestry. Located nearby are the magnificent temple

complexes of Angkor Wat. That national treasure attracts

tourists from all over the world and these tourists need to be

housed and fed. The expansion of hotels and restaurants in the

provincial capital of Siem Reap has been phenomenal. That in

turn has raised demand for real estate and so escalated the cost

of local land. The growth in business has benefited those with

opportunity and some capital, but it has largely left the rural

people behind, apart from a few who have been able to obtain

work in the service sector.

The main temple site of the immense and historic Angkor Wat

Temples

So, while foreign tourists can reside in 4 or 5 star

air-conditioned hotels, and enjoy good dining at cheap prices,

there is hardly a village in the surrounding countryside where

the people have access to clean water. Their schools are barely

equipped, and village school teachers get a poverty-level wage.

Health services are also minimal. Water-borne disease is the

main cause of high infant mortality. Tuberculosis is prevalent

as are dengue fever and malaria. And as elsewhere in the world,

HIV and aids are on the rise.

Now the land and water on which they rely for survival and

livelihood, has become an attractive commodity for business and

investment. The possible existence of petroleum deposits

underneath the basin could escalate the demand for ownership and

control of the land. So the future of the 3 million rural

inhabitants of that region of Cambodia, looks uncertain to say

the least.

Luxury hotels springing up in Siem Reap, near the Angkor Wat

site

The question such situations raise is – should land be traded

for the benefit of the wealthy and powerful, or should it not be

held in trust or controlled for the benefit of the whole

nation? If industrial development is to take place, should not

the enormous wealth it generates be shared substantially with

the people it has displaced from their generational source of

livelihood?

|

In the

Celtic lands, waged labour was needed in land-owner-controlled

industries such as fishing and processing seaweed for industrial uses.

But equally, the vacated land was wanted for sheep farming, wool being

more profitable than tenants. As for the Potato Famine, that was a

political famine. In both Ireland and Scotland tenants had become

over-reliant on the single crop that could produce high yields from

little land. Meanwhile, as the people starved, food was exported from

Ireland to English cities. These are colonial realities that have to be

faced so that our peoples can move on.

[Most of the above section

draws on Alastair McIntosh’s brilliant and scathing review of a book

written by Michael Fry, Wild Scots: Four Hundred Years of Highland

History, John Murray, 2005]

The

idea of individual or private ownership of of fixed parcels of land is a

relatively recent phenomenon, and by no means universl, writes Ed

Iglehart. It is the result of replacement of custom in earlier more

innocent societies by statute in later more individualistic societies.

When property is created by a legal title, transferable for money, the

deep relationship between land and occupier, gained through residence,

labour and improvement, can be ignored, and the land acquired or

disposed of at will. Absentee owners, inconceivable before, can evict

residents with the full support of the law.

Scotland and Land Reform

map of northwest Scotland

The

need for a reform of the law and taxation relating to land ownership and

use, is nowhere more pressing than in Scotland. That country has a land

area of over 19.0 million acres, 3% of which is urban and 97% is rural.

Over 16 million acres of the rural land is privately owned as follows:

|

One quarter

is owned by |

66 landowners in estates of |

30,700 acres and larger |

|

One third

is owned by |

120 landowners in estates of |

21,000 acres and larger |

|

One half

is owned by |

343 landowners in estates of |

7,500 acres and larger |

|

Two thirds

is owned by |

1252 landowners

in estates of |

1,200 acres and larger |

So, as

Ed Iglehart says, in Land and Democracy, quoted above, two-thirds

of Scotland is owned by one four-thousandth of the people.

(1999 Territory,

Property, Sovereignty and Democracy in Scotland,

www.caledonia.org

web site).

No one

has researched and advocated the case for land reform in Scotland the

past 20 years as much as Andy Wightman. Below are some excerpts from

one of his papers.

|

LAND AND POLITICS

Land and politics have been intimately related since the

beginnings of modern society. As Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued,

'The first man who enclosed a piece of ground and found people

simple enough to believe him was the real founder of civil

society' (Rousseau, 1754). In Scotland, as elsewhere, the

history of landownership began with a system of governance based

upon the feudal relationship between the Monarch and the

nobility - a system of land tenure still with us today 900 years

later and an indication if ever it was needed of the resilience

of Scotland's land laws and our historic failure, indeed

inability, to do anything fundamental about reforming them.

Rights over land which began as political rights of civic

administration, evolved over time and under the control of those

who possessed them, into full-blown property rights.

This transformation has been carefully and assiduously protected

and nurtured by landed interests for many centuries. And it has

been this careful definition and assiduous protection which has

denied Scotland the kinds of reforms enjoyed by our West

European neighbours. And closely associated with politics has

been the phenomenon of power - political power, economic power,

and cultural and social power. As Loretta Timperley observed in

her academic analysis of landownership in Scotland, 'Power and

land ownership have been synonymous in Scotland from time

immemorial'.

THE POLITICS OF LAND REFORM

The 19th and early 20th century saw radical action on land

reform and delivered lasting social and economic progress. In

the aftermath of the Second World War, however, despite Labour's

commitment to land reform, little has happened. It was not

until the 1970s that political attention again seriously engaged

with the land question. That period ended of course with the

election of the Conservative Government in 1979 and led to those

long years of political discontent in Scotland. Ideas have,

though, moved on since the 1970s. No longer, for example, is the

land reform debate conducted across the ideological divide

between private and public landownership. And the denial of a

land reform agenda by the Conservatives also resulted in civic

society picking up the issue and responding in a practical way

on the ground to the problems it faced. This approach, most

prominently captured in the activities of the Assynt crofters

and of the islanders of Eigg eschewed the barren rocks of

political ideology and instead generated a revitalised citizen's

agenda for land reform, an agenda it should be noted which has a

long and honourable history going right back to the Chartists

and the National Land Company, the Highland Land League, the

Stornoway Trust and the Scottish Farms Alliance.

For much of this country's recent history the political process

has failed to respond to 150 years of civic effort to promote

more equitable and socially beneficial forms of landownership

(Boyd, 1999). He argues that there have been four great

failures. These were:- the failure between 1840 to 1886 to

legislate to break up sporting estates and sheep farms into

smallholdings and thus secure the continuity of peasant society

in Scotland; the failure between 1890 and 1940 to legislate to

protect scenic landscapes, provide a right to roam and establish

national parks ; the failure between 1950 to 1980 to legislate

to fully protect and safeguard areas of national and

international significance to nature conservation and; the

failure between 1950 and 1999 to legislate to protect the public

and local community interest in land for livelihood improvement

and economic development.

Typical of the vast tracts of land in the

area which remain largely un-taxed

The lesson is that civic society can articulate and develop the

case for land reform but without the political means or will to

deliver, its efforts are largely in vain. The political means

are now in existence but what of the political will? How have

the various traditions in Scottish political life responded to

the need for land reform and what has been their record?

Labour, to the extent that it gave much thought to the land

issue at all over the past 20 years has, right up until recent

years, remained burdened with the legacy of state socialism and

state ownership - this was the response of McEwen himself to the

land question. The legacy goes right back to the early days of

the Labour movement. In response to the excesses of Victorian

and Edwardian capitalism, the left sought refuge in the power of

the state to solve economic and social problems. In the process

it rejected the social democratic model which had merged on the

continent.

A social democratic property owning society with strong mutual

and cooperative institutions exists right across Scandinavia and

Western Europe. Walk into any village in the Netherlands, in

France, in Denmark or Norway and you will find farmer-owned

supermarkets, banks and food processing factories. The

revolutions which swept Europe in the 18th century laid the

groundwork for today’s rural economy of small-scale proprietors

linked by a strong network of collective institutions which give

European social democracy a distinctive and culturally rooted

constituency of support.

In Scotland, however, two further centuries of landed power

prevented that pattern from emerging and so the engine for an

alternative social democratic model based upon co-operatives of

small scale proprietors controlling the land and economy was

lost. The Tories meanwhile were busy privatising public assets

and promoting a property-owning democracy which could be relied

on (or so it thought) to vote Conservative. What was

inconsistent about this ideology, was that it attacked public

monopolies but not private ones, and limited the ideals of

property ownership to the home. There was no promotion of a

property owning democracy in the countryside - precisely the

opposite in fact. Tory politicians would have as soon

countenanced an extension of a property owning democracy in

rural Perthshire as they would have engaged in a massive

programme of nationalisation of heavy industry. Some later

actions of Michael Forsyth did begin to acknowledge and develop

the idea on state-owned agricultural and forestry estates, that

giving individuals and communities more power over land was a

good idea and consistent with Conservative philosophy.

Andy Wightman, 6th

John McEwen Memorial Lecture on Land Tenure in Scotland,

1998 |

Croft settlements

Crofters at work on the Isle of Harris

The

issue of land reform is one then that concerns historical justice,

cultural and spiritual values, economic opportunity, sustainable

communities, and a taxation system that is truly fair and equitable.

There

is a much less well known and parallel need in Scotland, to address an

evil that has robbed communities of their assets, and continues to do

so. Much land and property in urban areas and countryside regions, was

classed as “Common Good Property”. This includes parks and museums and

libraries, parts of green belts and some buildings of charitable

institutions, that were donated to the townsfolk in years past, by

wealthy benefactors. These public assets have been brazenly disposed of

by Councils for private developments that benefit only the councils

themselves and the commercial developers. The whole process is illegal

and unethical, but has been perpetrated without any transparency or

public accountability, so that today few in our towns and cities realise

it has happened. Yet at the same time they wonder why council tax and

water charges escalate year by year. The assets they have been robbed

of by stealth, could have comfortably covered the costs of water,

schools or waste disposal.

While I

believe in a basic land tax, I recognise that there are other

imaginative ways in which taxation could support land reform and

sustainable land use. Lester Brown of the Earth Policy Institute, has

written about the value of an environmental tax which is being

introduced in a number of countries.

Lester Brown of the Earth Policy

Institute

“Several European countries are benefiting from a steady decline in

income taxes as governments lower taxes on income and raise taxes on

environmentally destructive activities—like burning gasoline or coal.

The purpose of this tax shifting is to incorporate the environmental

costs of products and services into the market price to help the market

tell the environment truth. This rewards environmentally responsible

behavior such as reducing energy use. Among the various environmentally

damaging activities taxed in Europe are coal burning, gasoline use, the

generation of garbage (so-called landfill taxes), the discharge of

toxic waste, and the excessive number of cars entering cities. Germany

and Sweden are the leaders among the countries in Western Europe that

are shifting taxes in a process known there as environmental tax reform.

A four-year plan adopted in Germany in 1999 systematically shifted taxes

from labor to energy. By 2001, this plan had lowered fuel use by 5

percent. It had also accelerated growth in the renewable energy sector,

creating some 45,400 jobs by 2003 in the wind industry alone, a number

that is projected to rise to 103,000 by 2010. In 2001, Sweden launched

a bold 10-year environmental tax shift designed to convert 30 billion

kroner ($3.9 billion) of taxes from income to environmentally

destructive activities. Much of this shift of $1,100 per household is

levied on cars and trucks, including substantial hikes in vehicle and

fuel taxes. Electricity is also being taxed more heavily. This tax

restructuring is an integral part of Sweden’s plan to be oil free by

2025.

Among

the other European countries with strong tax reform efforts are Spain,

Italy, Norway, the United Kingdom, and France. There are isolated cases

of using taxes to discourage environmentally destructive activities

elsewhere. The United States imposed a stiff tax on chlorofluorocarbons

to phase them out in accordance with the Montreal Protocol of 1987 and

its subsequent updates. When Victoria, the capital of British

Columbia, adopted a trash tax of $1.20 per bag of garbage, the city

reduced its daily trash flow 18 percent within one year. Cities that are

being suffocated by cars are using stiff entrance taxes to reduce

congestion. First adopted by Singapore some two decades ago, this tax

was later introduced by Oslo, Melbourne, and, most recently, London.

The London tax of £5, or nearly $9 per visit, first enacted in

February 2002 by Mayor Ken Livingstone, was raised to £8, more than $14,

in July 2005. The resulting revenue is being used to improve the bus

network, which carries 2 million passengers daily. The goal of this

congestion tax is a restructuring of the London transport system to

increase mobility and decrease congestion, air pollution, and carbon

emissions. While some cities are taxing cars that enter the central

city, others are simply imposing a tax on automobile ownership. New York

Times reporter Howard French writes that Shanghai, which is approaching

traffic gridlock, “has raised the fees for car registrations every year

since 2000, doubling over that time to about $4,600 per vehicle—more

than twice the city’s per capita income.” In Denmark, the steep tax on

an energy-inefficient new car doubles the price of the car.

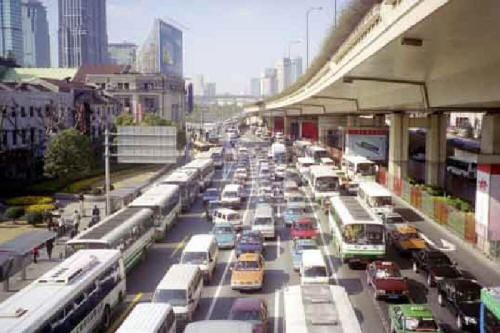

Traffic in the streets of Shanghai

London traffic

Traffic in Tokyo

An

excellent model for calculating indirect costs is a 2001 analysis by the

U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which calculated

the social costs of smoking cigarettes at $7.18 per pack. This not only

justifies raising taxes on cigarettes, which claim 4.9 million lives per

year worldwide (more than all other air pollutants combined), but it

also provides guidelines for how much to raise them. In 2002, 21 U.S.

states raised cigarette taxes. Perhaps the biggest jump came in New

York City, where smokers paid an additional 39¢ in state tax and $1.42

in city tax—a total increase of $1.81 per pack. If the cost to society

of smoking a pack of cigarettes is $7.18, how much is the cost to

society of burning a gallon of gasoline? Fortunately, the International

Center for Technology Assessment has done a detailed analysis, entitled

“The Real Price of Gasoline.” The group calculates several indirect

costs, including oil industry tax breaks, oil supply protection costs,

oil industry subsidies, and health care costs of treating auto

exhaust-related respiratory illnesses. The total of these indirect

costs centers around $9 per gallon, somewhat higher than those of

smoking a pack of cigarettes. Add these external costs to the average

price of gasoline in the United States—just over $2 per gallon in

2005—and gas would cost $11 a gallon. For Americans, this is shockingly

high, but it is not that much higher than the $9 per gallon that

British, German, French, and Italian drivers now regularly pay for

gasoline.

Asia’s

two leading economies -- Japan and China -- are now considering the

adoption of carbon taxes. For the last few years, many members of the

Japanese Diet have wanted to launch an environmental tax shift, but

industry has opposed it. China is working on an environmental tax

restructuring that will discourage fossil fuel use. According to Wang

Fengchun, an official with the National People’s Congress, “Taxation is

the most powerful tool available in a market economy in directing a

consumer’s buying habits. It is superior to government regulations.”

Environmental tax shifting usually brings a double dividend. In reducing

taxes on income—in effect, taxes on labor—labor becomes less costly,

creating additional jobs while protecting the environment. This was the

principal motivation in the German four-year shift of taxes from income

to energy. Reducing the air pollution from smokestacks and tailpipes

reduces the incidence of respiratory illnesses, such as asthma and

emphysema -- and thus overall health care costs.

Some

2,500 economists, including eight Nobel Prize winners in economics,

have endorsed the concept of tax shifts. Harvard economics professor

N. Gregory Mankiw wrote in Fortune: “Cutting income taxes while

increasing gasoline taxes would lead to more rapid economic growth, less

traffic congestion, safer roads, and reduced risk of global warming --

all without jeopardizing long-term fiscal solvency. This may be the

closest thing to a free lunch that economics has to offer.”

Accounting systems that do not tell the truth can be costly. Faulty

corporate accounting systems that leave costs off the books have driven

some of the world’s largest corporations into bankruptcy. Modern right

wing economists and businessmen cleverly externalise social and

environmental costs, in order to maximise corporate profits. In the

wake of their ruthless push for economic efficiency, we see an erosion

or collapse of pension provisions, a decline in health benefits, and

enormous increases in the cost to all consumers of basic services such

as water supplies.

The

risk with our faulty global economic accounting system is that it so

distorts the economy that it could one day lead to economic decline and

collapse. If we can get the market to tell the truth, then the world

can avoid being blindsided by faulty accounting systems that lead to

bankruptcy. As Øystein Dahle, former Vice President of Exxon for Norway

and the North Sea, has pointed out: “Socialism collapsed because it did

not allow the market to tell the economic truth. Capitalism may collapse

because it does not allow the market to tell the ecological truth.” One

might add that neither system was prepared to recognise the spiritual

truth that they both devalued and degraded their human capital.

Oystein Dahle,

former Vice President of Exxon Norway, now Chairman of the WorldWatch

Institute |