|

“At this festive season of

the year, Mr Scrooge,” said the gentleman, taking up a pen, “it is more

than usually desirable that we should make some slight provision for the

poor

and destitute, who suffer greatly at the present

time. Many thousands are in want of common necessaries; hundreds of

thousands are in want of common comforts, sir.”

“Are there no prisons?”

asked Scrooge. “Plenty of prisons” said the gentleman, … but under the

impression that they scarcely furnish Christian cheer of mind or body to

the unoffending multitude, a few of us are endeavoring to raise a fund

to buy the poor some meat and drink, and means of warmth. We choose this

time, because it is

a time,

of all others, when Want is keenly felt, and when Abundance rejoices.

What shall I put you down for?”

“Nothing!” Scrooge replied. “You wish to be anonymous?” “I wish to be

left alone” said Scrooge. “Since you ask me what I wish, gentlemen, that

is my answer. I don’t make merry myself at Christmas, and I can’t afford

to make idle people merry. I help to support the prisons and the

workhouses — they cost enough — and those who are badly off must go

there.”

“Many

can’t go there; and many would rather die.” “If they would rather die”

said Scrooge, “they had better do it, and decrease the surplus

population.”

* * *

* *

From

the foldings of its robe, (the Spirit) brought two children; wretched,

abject, frightful, hideous, miserable. They knelt down at its feet, and

clung upon the outside of its garment. “Oh, Man ! Look here. Look,

look, down here !” exclaimed the Ghost.

They

were a boy and a girl. Yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish; but

prostrate, too, in their humility. Where graceful youth should have

filled their features out, and touched them with its freshest tints, a

stale and shrivelled hand, like that of age, had pinched, and twisted

them, and pulled them into shreds. Where angels might have sat

enthroned, devils lurked, and glared out menacing. No change, no

degradation, no perversion of humanity, in any grade, through all the

mysteries of wonderful creation, has monsters half so horrible and

dread.

Scrooge

started back, appalled. Having them shown to him in this way, he tried

to say they were fine children, but the words choked themselves, rather

than be parties to a lie of such enormous magnitude. “Spirit ! are they

yours?” Scrooge could say no more. “They are Man's,” said the Spirit,

looking down upon them. “And they cling to me, appealing from their

fathers. This boy is Ignorance. This girl is Want. Beware them both, and

all of their degree, but most of all beware this boy, for on his brow I

see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased”.

“Have they no refuge or

resource?” cried Scrooge. “Are there no prisons?” said the Spirit,

turning on him for the last time with his own words. “Are there no

workhouses?” The bell struck twelve.

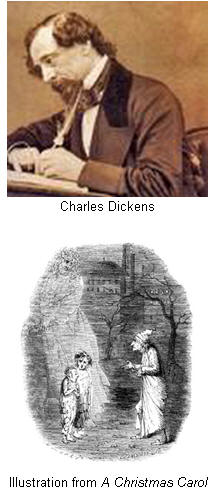

From A

Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens

Memories of childhood years that are still vivid in my mind, include

some glimpses of the impact of poverty, unemployment and homelessness on

men and women made in God’s image. We saw little destitution in

Morayshire, unlike what existed in Glasgow and the cities in England in

the immediate post-war years. But I will never forget men singing in

the street as they sought a few pence to supplement their meagre diet.

One semi-invalid old man in our town played a gramophone on the

sidewalk. There was no begging, but these victims of misfortune sought

to entertain passers by with a little music. Those among them who had

seen active service in the first world war would display their few

medals to attract sympathy.

One hot

summer’s day 50 years ago, I went into an Elgin café for a lemonade. A

poor elderly woman came in with two shabbily dressed men, presumably

relatives who were visiting her. I guess she lived in one of the ‘doss

houses’ for homeless persons. They sat down at a table and when the

waitress came the woman asked for two glasses of water. The waitress

kindly brought them without question. The woman then laid two pennies

(two old pence) on the table as payment. Despite the heat, she did not

ask for a glass for herself. That simple incident has remained impressed

on my memory. I still feel the embarrassment that a young teenager

could be well-dressed and enjoy a sweet cold refreshment, while three

aged citizens could barely afford a glass of water. Yet it was nothing

in comparison with the horrors of life then in slum parts of some of our

major cities.

In

later years I was to observe want and deprivation in its various sad

forms in many parts of the world. I recall an old fellow in a village

to the west of our station in the Zambesi valley in Africa. I guess he

had no living relatives as he was destitute and depended on the

generosity of the village which itself had little to offer. The guy was

a bit simple, perhaps slightly senile, and came up to the District

Officer who was conducting a brief meeting with local leaders. Despite

the attempts of the Boma guards to usher him away, the old man kept

asking for some provision. I was later to send him some clothing, and

modest supplies of food we could easily spare, whenever our truck went

that way, until the poor fellow passed away.

In

Turkmenistan, it used to pain me to see old people sitting on the

pavement with a few simple possessions laid out on a cloth for sale, or

to see a group of ‘babushka’s’ with hungry faces, examine some

frozen kilka sprat and calculate whether between them they could

purchase enough to form the basis of a single meal. The tattered clothes

and hungry expressions of unemployed or under-employed people in African

states like Mozambique and Sierra Leone during their difficult years,

are also imprinted on my memory.

But

even now, in the 21st century, the social problems persist.

Very recently I met a woman who was selling the Big Issue outside large

stores in Scotland. She had been a victim of domestic abuse, and I

understand had an addiction problem for a period. But during bitterly

cold winter weather, she was sleeping in a tiny tent on waste land by a

river. Some friends worked tirelessly to get her accommodation and some

income support, but it was not easily obtained or approved. If anyone

thinks that our welfare system is over-generous, or panders to the idle

and spongers, - let them find a genuine case of need and try to guide

them past the bureaucratic hurdles, and the gatekeepers who can deny

assistance for any of a multitude of reasons.

Unemployed man selling the Big Issue

It is

the human cost of society’s failure to provide for the sick or aged, or

those deprived of work, that impacts most powerfully on our hearts and

consciences. As one of the earlier sincere socialist MPs said when

showing a friend around homes in Glasgow’s slums, - “It has to hit

you here”, striking his breast. “You have to feel it in your

gut”.

I

comment elsewhere on the imperfections of our modern safety nets and

welfare systems, on the importance of seeing these issues as society’s

responsibility rather than just the government’s job, and on the need to

provide motivation and opportunity for people to undertake remunerative

work. But I believe it is absolutely vital that we understand the need

for those measures, and the dreadful results of inaction, before we

begin to criticise current welfare systems.

Welfare systems are

under increasing pressure as we enter the 21st century. They

are beginning to be seen in some quarters as a well-meaning but naive

experiment that has had its day. National health provisions, free

education, old age pensions, unemployment benefit, council housing,

disability allowances, and other provisions for the disadvantaged or

deprived, are now being eroded if not wholly abandoned. To discuss the

issue in a knowledgeable way we need to go back to the beginning of the

welfare state – to the Beveridge Report, - and even beyond that, - to

the social evils of the previous 200 years.

The industrial

revolution brought with it much social upheaval. Previously the bulk of

employment was to be found on the land, or if in towns and cities, in

businesses of relatively small size. People mostly lived where they

worked, and worked in direct contact with their employer. Though cash

wages were very small, accommodation and food were usually provided, and

workers ate from or at the employer’s table. Most companies were family

firms producing life’s necessities like crops, fish, meat, flour,

cheese, wool, thread, clothing, shoes, leather, pottery, kitchen ware,

tools, charcoal, candles, and furniture. Most people lived and worked

in the same locality all their lives. This was the norm in Europe

before industrialization, and remains to some degree in parts of the

poor countries of Africa and Asia. Mechanisation of farming, and growth

of heavy industry and large scale manufacturing, changed the lives and

conditions of workers and their families. People now worked for wages

out of which they had to pay for housing, food, and other necessities.

The result was often urban squalor and poverty. Employers paid little

heed to the low quality of life of their workers. It took the early

reformers like Lord Shaftesbury, activists like William Booth, and

writers like Charles Dickens, to expose the shame of industrial

exploitation in wealthy Britain.

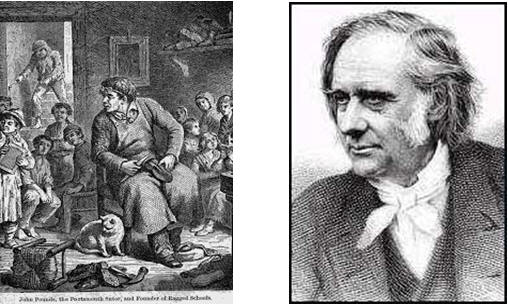

Ashley Cooper, Lord

Shaftesbury William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army

In 1815 John Pounds of

Portsmouth, a crippled shoemaker, was one of the first to provide free

education for poor children. His were the first of the “ragged

schools”. He was followed by Thomas Guthrie in Scotland, and by Ashley

Cooper, the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury in England who did much

to promote the education and welfare, and relieve the suffering, of the

poor.

John Pounds, the cripple

shoemaker Thomas Guthrie who

pioneered

who started shools for poor children

schooling for poor children

Drawing of a “ragged school”

A Guthrie school

An amazing education

initiative in Cambodia

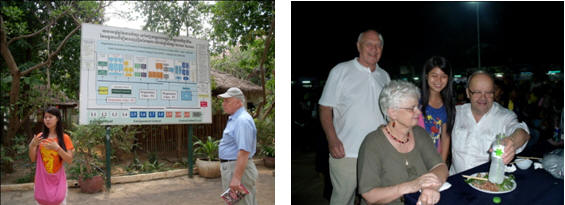

In 2008 our project office in Siem Reap, Cambodia, was asked

to accept three pupils for work experience which we gladly did. The

pupils, all girls, were orphans who were being educated at a large

school in Phnom Penh, established exclusively for children who were

orphaned or destitute from family break-up, abuse, or social

deprivation. The three delightful pupils were a pleasure to have assist

us in the office, and on their departure they invited me to attend their

graduation ceremony in the capital, due to be held a few weeks later. I

gladly did so, and was overwhelmed by what I saw.

The school, beautifully named “Pour un Sourire d’Enfant”

(“for a smile on the face of a child”), had been founded by a

remarkable French couple, Christian and Marie-France des Pallieres, in

1996, after they saw the appalling conditions of homeless or orphaned

children on the rubbish dumps of Cambodia’s capital city. Together in

1993 they set up the association the school took its name from, and

began with six children rescued from the dumps and the streets. The

children were filthy, under-nourished, and suffered from a range of

health problems. Their hair was matted and greasy. Over the next ten to

eighteen years, “Papa” as he came to be known as by the pupils, assisted

by his wife and a small staff and band of volunteers, established and

developed the marvellous PSE school.

From the beginning there was strict adherence to basic

principles. All children enrolled had to be genuinely destitute or

orphans. They were housed with relatives or foster families. Those who

could not return to their homes due to the dangers of abuse or drugs or

criminality, were housed in a school dormitory. All children were fed

and provided with uniforms. The education, meals, uniforms, and medical

attention were provided absolutely free. Discipline was strict. Absence

without just cause meant the pupil had to clean toilets and yards next

day. More than 3 days absence without cause meant dismissal. Another

principle was that the school accepted no financial help from national

authorities, but was careful to sign agreement protocols with the

government. The Royal Government of Cambodia later recognised the

valuable service of Monsieur and Madame Pallieres by granting them

honorary Cambodian citizenship.

By

the time I visited the school, there were 3,000 pupils. Graduates

already numbered 2,000 all of whom had obtained jobs. The school gained

such a reputation, employers were keen to take on ex-pupils who were

disciplined and eager to work. The PSE set up a small trade school wing

to equip graduates with skills for the vehicle, mechanical, food,

tourism, and hotel industries.

A personal observation

: I am sure all of us looking back on our lives would love to have

helped at least one destitute child to get an education and preparation

for a decent life and a job. To have helped ten or twenty would be

superb. Amazingly, Christian and Marie-France des Pallieres have given

such help to 5,000 children !

Above Sokuntheary, one of the first six children

rescued off the city dump in 1993, explaining the structure and

programmes of PSE. She is now attending university. Above right,

“Papa” and “Mama”, Christian and Marie-France des Pallieres, the

remarkable founders and directors of “Pour un Sourire d’Enfant”. Behind

them is former pupil Sokuntheary, and myself. (information at

www.pse.asso.fr

)

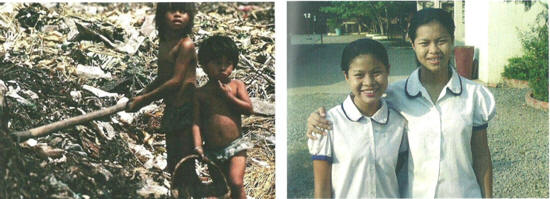

Flashback below: Little Sokuntheary (right) and her sister Thiery as

they were when found by the des Pallieres, scavenging on the city

rubbish dumps in 1993. On the right, the two sisters when pupils in the

PSE school, “Pour un Sourire d’Enfant”. Sokuntheary is on the left.

Sokuntheary and her sister when

scavenging on the city dump, and later in the PSE school.

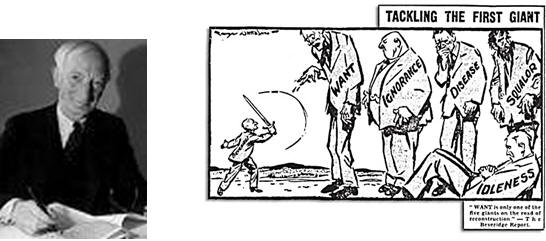

The UK Welfare State, and the five giants

By degrees, the poor

law provisions, and attempts to introduce health care, free education,

better housing, and relief for the destitute, invalid or unemployed,

made life better for the needy and disadvantaged. None of these

measures were adequate and there was no comprehensive attempt to create

a national system of welfare, until in 1941, a 62-year-old civil servant

with a flair for manpower planning and management, was asked to chair a

committee on co-ordination of social insurance. Sir William Beveridge

was bitterly disappointed by the apparent demotion of a man of his

abilities and service record, but eventually set about the task with his

legendary capacity to grapple with complex and intractable problems, and

to forge a workable framework out of the confusion and chaos. He

recognized five ‘giants’ to be confronted on the road to a just and

equitable society; - Want; Ignorance; Disease; Idleness; and Squalor.

They were to be tackled by a comprehensive raft of measures that were to

include a national health system, unemployment benefit, old age

pensions, free education, and widespread housing provision. His report,

an instant sell-out, was published on the first of December 1942. It was

to out-sell every HMSO publication until the 1960’s. Its radical

proposals were largely implemented within the next ten years. This was

an immense achievement by any measure.

William Beveridge, architect of

Cartoon of Beveridge’s “five giants”

Britain’s post-war welfare state

In the Introduction,

Beveridge mentioned three principles. First he wrote that the time was

ripe for a revolutionary movement. Second, that the social security

system was primarily an attack on Want, but that Disease, Ignorance,

Squalor and Idleness, had also to be addressed. His third principle was

that of cooperation between the state and the individual. Beveridge

said that “the State should offer security for service and

contribution, (but) in organizing security it should not stifle

incentive, opportunity, and responsibility … for voluntary action by

each individual to provide more than the minimum for himself and his

family.” He was to broadcast details of his proposals and to

address packed meetings, batting down the critics who said that the

proposals would lead to feather-bedding and moral ruin. To an American

who claimed that if his ideas had been in force during the Elizabethan

era, there would have been no Drake, Hawkins or Raleigh, he responded

“Adventure comes, not from the half-starved, but from those well-fed

enough to feel ambition”.

Being two years old

when the Beveridge Report was published, I guess I was one of the first

generation to benefit from the welfare state from childhood. Apart from

wartime and post-war rationing, we saw little of the hardships or

deprivation that were widespread in the first half of the 20th

century. Pockets of squalor and misery remained in the slums of the

large cities, but we saw little of them in rural Scotland. In the 1950’s

we looked forward with confidence to a lifetime protected by cradle to

the grave welfare provisions. But the utopian scheme began to show

signs of stress by the 1970’s. Its cost escalated, and some sections of

society began to be trapped by the welfare rules, in a situation of

hopelessness, while others exploited the system dishonestly. What was

more disturbing was the spread of depression and related illnesses among

welfare recipients. Communities of unemployed or low-paid workers lived

in ghettos of dreadful multi-storey flats or ugly council flats.

Hostile anti-government and anti-authority attitudes flourished like

weeds on waste ground, together with bitterness towards those fortunate

enough to have decent jobs, houses and automobiles. This of course was

not true of all unemployed or all persons on low wages, but those who

maintained dignity and self-respect in those circumstances were probably

a minority.

Then, with the arrival

in power of Margaret Thatcher, the principle of the welfare state began

to be questioned, its provisions reduced, and its structures

dismantled. What she began, Tony Blair has continued with a missionary

zeal, which is amazing for a supposedly Labour politician. The

Government appeared to wash its hands of responsibility for prescription

costs, dental treatment, old age pensions, and free tertiary education.

Both Prime Ministers had the weight of right wing capitalist thinking

behind their policies. The argument ran along the lines that however

good and well-meaning the original Beveridge plan was, the idea was

naive and ultimately unworkable due to the increasing costs of and

demands for the services. This logic was reinforced by national economic

decline, an aging population, and expensive new technologies available

to the medical and defense sectors. Its proponents could point to the

collapse of communism and socialism throughout the world to confirm that

only monetarist, capitalist policies could work in the long term.

Someone has noted that while the communist threat remained, the gap

between the wealthy and the low-paid was within reason. Following the

collapse of the Soviet Union, that gap has tripled in the United States.

Early days of the welfare state

Correlli Barnett has

been one of the most eloquent and forceful critics of the welfare sytem

which along with loss of empire and trade union power, he blamed for the

steady decline of Britain since World War II. In The Audit of War,

he identified post-war socialist policies and adoption of the

Beveridge Report as responsible elements in deterioration of British

power, wealth and influence. He also attributed blame to our lack of

investment in industry, and to higher education institutes and

universities which undervalued science and technology, and gave primacy

to classical subjects. I am inclined to agree with him on the latter

point, though today we seem to have ditched the classics, but instead of

investing in science, have filled our curriculums with ‘politically

correct’ and socially acceptable subjects. As one who has been involved

in development of technical and science education in developing

countries, I can confirm that they are not cheap options, and that in

every organized society there is a weight of suffocating, bureaucratic

influence that favours sterile theory over practical skill and

scientific knowledge. But was Barnett correct in his critique of the

welfare state, and his analysis of Britain’s problems ? The following

excerpt from Nicholas Timmins’ book gives us much food for thought. [Nicholas Timmins,

The Five Giants, a biography of the welfare state, Harper

Collins, 1995.]

|

Facts and

Myths about the Welfare State

In examining

social policy in Britain, for all its myriad faults, it seemed

that some form of collective provision was the least bad way of

of organizing education, health care, and social security. The

challenge was how to improve the welfare state, not how to

dismantle it. Virtually every day since 1948, the NHS has been

said to be in crisis. Each time unemployment rises, the

unemployed are blamed as work-shy scroungers. (The ‘scrounger’

accusation is also thrown at immigrants each time their numbers

increase.) We should challenge the myth that there was a Golden

Age when a lavishly funded welfare system operated in a rosy

glow of consensus. But we also need to expose the myth that the

Conservative party never really supported it, and always had

plans to dismantle it. And we should recall that the Labour

party (including Gaitskell) also at times had draconian

proposals to slash benefits. On the extreme right, some saw

satanic socialists bent on controlling the nation by

cradle-to-grave feather-bedding, that would sap its moral fibre

and take the ‘Great’ out of Great Britain. One must look at

what actually happened, not at the thoughts harboured by some in

each side. The welfare state and its boundaries is a being that

moved back and forth under both parties the past fifty years.

It is

impossible now (1995) to travel on the London underground or

walk the streets of our big cities without finding beggars.

That, in my lifetime, did not happen before the late 1980’s.

There were down-and-outs on the Embankment. There were places

that housed alcoholics and others who fell through the safety

net. But there were no young people, their lives blighted,

sleeping in doorways in the Strand. Yet the welfare state still

exists. Its services still take two-thirds of annual government

expenditure totaling £ 250 billion. It can hardly be said to be

dead. However, create a strong enough perception that it is

dying, and you make it easier to lop off further chunks without

anyone asking where they went.

(from The Five

Giants, adapted and abbreviated for space purposes) |

Having spent over half

my life trying to improve the lot of poor farmers, fishermen and

artisans in Africa, Asia, the Far East, and the Pacific, I am inclined

to view our state welfare system as a poor substitute for care by the

family and the community, which is what does the same job in the poorer

parts of the world. The more the welfare system is divorced from the

recipients’ relatives and neighbours, the more he or she is tempted to

take advantage of its provisions, which so many do in a variety of

ways. My sister-in-law in Canada worked as an industrial nurse for a

period, and was regularly depressed and annoyed by the blatant pretence

of healthy employees claiming disability payments from their employers

(most often from ‘backache’ which was difficult to disprove medically).

A more serious and more

widespread misuse of welfare and medicare, is carried out knowingly or

unwittingly by thousands of patients who treat the health service as a

panacea for emotional, psychological or nervous troubles that in many

cases are self-inflicted or self-perpetrated. I have lost count of the

number of doctors who have complained to me about such people who make

up so much of their work. Now I am sure some will hold their hands up

in horror at my prejudice and lack of sympathy, but my argument is that

for many such unfortunate persons, the cure, or rather the healing, lies

elsewhere. And my own view as a total amateur in medicine, is that

pharmaceutical drugs often compound or aggravate the problem, or else

reduce the patient to a state of dependence. Of course, there are

genuine and serious cases of mental and emotional illness that some

medications and professional counseling can help. But too often such

illness is a result or symptom of a society that has ceased to care,

that has eroded human and family values, and that feeds its victims on

trash diets, both mental and physical, that can only add to the

malfunction of body and soul.

Doctor attending a patient

Pharmacy shelves of drugs and

medicines

Unemployment benefit

and its related allowances, that were such a life-saver to families

during the depression, have become for many an obstacle to

re-employment. I met numerous persons who dearly wanted to work but

were caught in the welfare trap. Then there are those who have lost all

will to work and turn their energies instead into maximizing the number

and range of benefits they can extract from the system. Although

brought up in a socialist family, I have always felt that no-one really

wanted the ‘dole’ as we termed unemployment benefit. People wanted a

job that gave them dignity and something to take pride in and yield an

adequate income that they had earned by their own efforts. Hand-outs

could never do that. The old Pauline church rule that said “if any will

not work, - neither should they eat”, may seem severe to our modern

ears, but that is pretty well the situation in poor countries where the

invalid and aged are cared for, but not the indolent.

Management systems

So what is wrong with

our systems that we spend such colossal sums on and yet from which we

see such poor or unsatisfactory results ? Two major mistakes in my

view are - too much emphasis on management, and too little attention to

actual impact or desired outcome. Numerous informed students of the

situation have come to similar conclusions. Good management is

something all businesses and societies want, but the management systems

themselves contain the roots of their excessive and perpetual growth.

In the jargon of that science, this is known as “positive feedback”.

Elements that support

the self-perpetuating tendency, are the obsession to document

everything, and the technique of appropriating power through control of

financial and staffing decisions. Despite numerous attempts to reduce

or limit the growth of bureaucracy, few governments or large

organizations have been able to do so. Governments of both the liberal

and conservative persuasion (but mainly the conservative ones), have

been elected on manifesto pledges to cut bureaucracy. Practically all

have failed. The administrative juggernaut rolls on regardless. The

consequences of management proliferation, according to David Ehrenfield,

are – bad decisions, demoralization of producers, and the loss of

skilled practitioners or their replacement with ‘paper pushers’. We

can all recount umpteen examples of the stupidity and pointlessness of

modern management decisions that cause despair and frustration in the

workforce, yet are defended like infallible doctrines by the high

priests of our administrations.

On the subject of

management proliferation, one of our parishioners in Edinburgh once

asked me to accompany her to a social services hearing on why her

children were not attending school. She was a pleasant and decent women

in her own way, but like many in her situation, could paint a picture to

present herself in the best light. She waxed eloquent about the lack of

support from her husband, and even hinted at his drinking (I knew the

man and he drank sparingly if at all, and was often alone caring for the

kids when I visited the home). The real reason I surmised for the

children’s non-attendance was the cost of their bus fares which the

social services would not pay since they could have attended a school

within walking distance but somehow chose not to. However, that is all

just background to my point. The meeting we attended took well over an

hour. There were about 15 professional social officers and school

administrators of one sort or another in attendance. Only the

chairperson spoke, and no-one challenged any of the mother’s statements,

but instead nodded sympathetically at every point made. In the end no

decision was made that I recall, so the children continued to skip

school as often as they pleased. My point is that if this was typical,

- one solitary case demanded the attendance of large numbers of paid

officials, then – a). the system is very poorly managed in terms of

productive use of personnel, and b). since there appeared to be zero

result, much of the system and its operation, is quite ineffective. I

called the chairperson later and offered my own perception of the

problem from my knowledge of the family, but she dismissed my views.

Do we not need to focus

on the ultimate aims and objectives of our organizations ? All our

expenditure of money, energy and labour in health, education and welfare

systems, has to have a clear goal, and these objectives are really quite

simple, if difficult to realize. We want our people to be healthy. We

dearly want our children to be able to read and write and count, and to

acquire skills appropriate to their chosen careers. We want to treat

our aged and infirm with dignity and care, and to provide those going

through a period of no remunerative work, with the necessary temporary

assistance to survive and find fresh economic activity.

Most of the medical

profession will agree that our health services need to focus more on

holistic medicine and livestyles that are preventative towards disease

and illness. We also need to move more and more towards dietary cures

and use of herbal remedies and other natural medicaments. We should be

reducing our reliance on manufactured drugs, and cutting back on

non-essential operations. As long term goals we need to aim to minimize

the number of new tobacco addicts, and binge drinkers. And let us in

the name of sanity, protect our children from the proposed legalization

of marijuana. It would also help if we could cut drastically the

consumption of sweets, soft drinks and sugared cereals, especially in

children. We do not need to be kill-joys. One can make a soft drink or

iced lollipop from fresh fruit juice, just as easily and almost as

cheaply as from sugar, flavouring and colouring.

Education

Our schools and halls

of learning have become battlegrounds for control by political

correctness brigades, and experimental laboratories for those who would

encourage and teach abominable soul-less secularism, individualism and

weird lifestyles. As Professor John McKnight has put it, ‘the

bereavement counselor has replaced family and friends’ and kids are

conditioned to think they can handle grief without tears. The poor

teachers themselves are, like the policemen and women, made to be

scapegoats for society’s failures. Discipline and correction are dirty

words. Teachers have to spend more and more of their time on mindless,

meaningless form-filling, while our children graduate with less and less

ability in the three ‘R’s. In higher education we are neglecting

science and engineering, literature and history. Let’s have less

modernism and novelty subjects, and more of the bread and butter of the

subjects that are of most value to society.

Schoolchildren (in Thailand)

Numerous attempts have

been made to improve education in recent years. The most interesting

are those that focused on the worst performing schools in Britain and

America. The common reaction of politicians and shallow observers could

be summed up as “bashing the teachers; despairing of the pupils; and

moaning about the budgets” ! My own conversations with teachers has

increased my estimation for the dedicated people in that noble

profession. But I have been made deeply aware of the problems a school

faces when pupils are drawn from districts characterized by

unemployment, crime and vandalism. Even in less troubled towns and

districts, our schools can be a battleground where society’s ills are

reflected in loutish behaviour, bullying, and lack of respect. Drug

dealers push their wares through children in the playgrounds and

toilets. Given the unfavourable background, it is a miracle that our

kids still obtain a reasonable schooling.

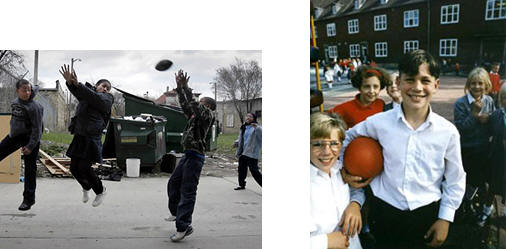

School

playgrounds – happy places, or sites of bullying?

Among the successful

programs in dfficult parts of U.S. cities, one worth considering is

described by William Ouchi in his book Making Schools Work. The

approach involved giving maximum independence and flexibility to each

school so they could better cater for the needs of the local district

and its population. Principals became autonomous and not subject to

administrators. The decentralized system had seven key elements, all of

which are deemed needful. They were : 1. principals become

entrepreneurs; 2. schools control their own budgets; 3. everyone is

accountable; 4. authority is delegated throughout; 5. student

achievement is a major focus; 6. the school becomes a community of

learners; and, 7. there is real choice for families. The results were

remarkable, given the pre-program situation. Pupils’ grades rose

dramatically, general behaviour improved, and admission applications

increased. Here there is much food for thought for our central-

government-controlled, bureaucrat-managed, politically-directed, systems

of education.

Sir Ken Robinson, the brilliant author of “Being in Your

Element”, and UK Commissioner of Creativity, has written and lectured

widely on the flaws and failures of much of modern education. He quotes

figures that show how 33 per cent of young people drop out of formal

schooling, or suffer through it without being inspired or equipped by

it. On the other hand, our colleges and universities are churning out

thousands of graduates who cannot find employment. The graduates simply

do not have the skills that employers are looking for today.

He believes our whole system of education is based on a 19th

century model, an inert system of linear planning, based on the needs of

industry and the civil service, and fails completely to encourage

imagination and creativity. Teachers and inspectors trained in the old

model, have a very narrow view of the purpose of schools, and use

extremely limited criteria to assess a pupil or student’s abilities and

competence. When such officials are confronted with the failures of

conventional education, - rather than seeking a radical reformation of

the whole approach, - they simply try to enforce the old system in the

hope it will work more effectively.

Robinson’s brilliant analysis focuses on human development

which is organic, and parallels the ecological principle of diversity.

Yet in most of our institutes of learning and systems of education, we

stifle natural aptitudes and largely ignore the value and potential of

imagination that has the power to excite young people and activate their

latent creativity.

Roger Mullin has commented : “Sir Ken Robinson is not alone

in his analysis of education. His type of critique has led to many

social/educational experiments over the years from pre-school (such as

free play, outdoor learning where it is the young child effectively who

determines the focus of learning) through to experimental home learning,

schools, open universities, and so forth. Unfortunately, almost all

such initiatives are taken by the private sector as most governments

continue to cling to the 19th century model.”

I am not an academic,

but I did teach at a university for two years, and worked on the

establishment of another, as well as undertaking curriculum development

and upgrading of staff, for several more. I found that some professors

had remarkably broad minds, sharp intellects and a great depth of

knowledge. Rather many others appeared sterile, devoid of imagination,

and quite ignorant outside of their narrow field of specialization. It

is said that our universities are know-how institutions, when they

should be know-why institutions. We need to move them away from ‘the

crushing weight of unevaluated facts’ or ‘bare-bones cognition’ towards

an understanding of life and humanity, value and purpose, and the

inter-connectedness of the whole natural world to man’s long-term

survival. Science is important, but not in isolation from the most

serious problems we face. Cleverness is not understanding. An IQ test

may measure intelligence, but it tells us little about our wisdom,

character, loyalty and moral stamina, - which are the qualities that

will determine the kind of contribution we will make to the world

regardless which career we may follow. Universities need to be freed or

protected from pure commercial or political pressures that would direct

them into production of graduates equipped mainly to design expensive

synthetic drugs, ever-more powerful weapons, or more sophisticated ways

of managing, controlling and manipulating the public at large.

Arthur Herman’s

fascinating book on the Scottish Enlightenment traces the influence of

Scots writers, artists, theologians, doctors, engineers, lawyers,

architects, missionaries, businessmen, shipwrights, soldiers, teachers,

reformers, and explorers, who together had an enormously beneficial

impact on the rest of the world, out of all proportion to the size of

their country. Their devotion to learning and to the betterment of

society was based on a strong sense of moral discipline and personal

initiative. This in turn was largely due to the moral and spiritual

focus, and its basis in Biblical theology, of the Scots universities and

their men of learning. Few today realize how much of that kind of

instruction made up the education of Adam Smith, Allan Ramsay, James

Watt, Robert Adam and Walter Scott. One wonders what they would make of

the brazen Philistine attitudes of many in academic life and the media

in Scotland today. A quotation* from Herman’s book is relevant:

“They saw the doctrines

of Christianity as the very heart of what it meant to be modern.

Robertson said, ‘Christianity not only sanctifies our souls, but refines

our manners’. As Hugh Blair put it, religion ‘civilises mankind’. …

‘Industry, knowledge and humanity are linked together by an indissoluble

chain’. It makes men free, and enlarges their power to do good. Virtue

and enlightenment move together step by step.”

[A

Select Society : Adam Smith and his Friends, The Scottish

Enlightenment, Arthur Herman, 4th Estate, 2003]

So, while we think

about education – when oh when are we going to stop our amazingly potent

and powerful media and communication systems becoming dominated by the

vile, the stupid, the sensual, the sordid, and the sensational? The

lowest common denominator prevails on television and in the pages of the

tabloid press. The internet has given the world’s pornographers and

paedophiles direct access to our children for their rotten wares and

foul imaginings. Surely it is not beyond the powers of governments to

place controls and limits on the spawn emitted from depraved minds and

unscrupulous profiteers. One gets the strong impression that no one in

government or the judiciary has the political will or the moral backbone

to do anything about it.

Family watching television

Pensions

Old age pensions have

become impossible for governments to sustain. Britain collected

contributions from its working population for the past fifty years, and

instead of investing the money, squandered it in the (false) hope that

there would always be enough new contributors to maintain a cash flow to

cover the pensions. Now all governments realize too well that our

senior citizen population is increasing while the relative number of

wage earners is decreasing. That is a recipe for bankruptcy of

government pension schemes. The problem is going to get worse before

replacement schemes are fully developed. So what can be done?

One suggestion of our

government is for us to delay retirement. While I feel repugnance at

the callous and calculating proposals of our current administrations,

this suggestion is one that I think has value, but for very different

reasons from those of our treasury. Men in particular, need to work.

Work should be and can be therapeutic, fulfilling and satisfying, quite

apart from any earnings it generates. Too many men deteriorate

physically and die much sooner than they should because of lack of

exercise for body and mind, and general lack of interest in life. Even

a modest pastime like gardening, or golf, or model making, can be a

splendid tonic to a senior citizen. But I also believe that those with

a lifetime’s knowledge and skill should continue to use it, whether in

the workplace, or in training others, or in voluntary work at home or

abroad.

Our prosperity as a

nation or people, (and our basic happiness), comes as much from our

consumption patterns as it does from our earnings. It has been said

that the richest person in the world is not the man who has the most,

but the one whose needs are met. If we focused on our real needs rather

than our greeds, we would be much more contented. In energy use, we

could save enormously by the simple measures of insulating our houses

and utilizing low fuel consumption vehicles. So, in the national

economy we could retain and increase wealth by reducing wasteful

expenditures. A good start could be made by cutting back on

sophisticated military hardware.

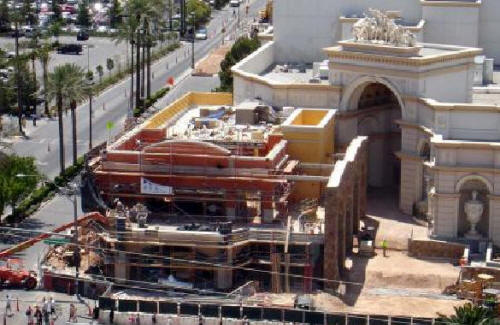

A mega-casino in Nevada, USA

A mega-casino in Macao, off China

New Labour’s ministers

would promote the growth of mega-casinos as they encourage and cash in

on, the obscene national lottery. Television programmes, from the ‘Who

Wants to be a Millionaire’, to the ‘prosperity gospel’ evangelists,

operate on the principle of encouraging and inflaming covetousness and

greed. Our grandparents believed that was a bad thing to do. We have

tried to make it a virtue, and a source of entertainment. No one talks

about the old-fashioned values of contentment and self-control. Yet

they are far, far more likely to produce genuine happiness and serenity

than any of the appetite-inflaming productions of today’s hucksters and

charlatans. One day maybe, we will learn wisdom. But perhaps, sadly,

only after we have ruined ourselves and spoiled our children, pursuing

the sham attractions of “Vanity Fair” in its 21st

century forms.

Drawing of Vanity Fair from Bunyan’s

allegorical book, Pilgrim’s Progress

|

What Adam Smith

really said

In much of

today’s press and media, there is a caricature of Adam Smith and

his writings, - chiefly The Wealth of Nations, that

presents him as the father of modern capitalism in its most

extreme and uncaring aspects. It might be helpful and

educational to take a closer look at what this gifted and

eminent Scottish thinker and writer actually believed and said.

Born in

Kirkcaldy in 1723 , the son of a customs inspector, Adam Smith

first thought of becoming a minister or a lawyer, but once

coming under the influence of Professor Hutcheson in Glasgow

University 1737, set his heart on being a moral philosopher.

Francis Hutcheson was the son of a Presbyterian minister in

Northern Ireland. He lectured on Natural Religion, Morals,

Jurisprudence, and Government, as well as delivering Sunday

sermons on the excellence of the

Christian religion.

Hutcheson

focused much on the freedom and happiness of society. He

believed that freedom’s ends were governed by God through our

moral reasoning and taught that the nature of virtue was as

immutable as the divine Wisdom and Goodness. Smith was to

succeed Hutcheson to the Chair of Moral Philosophy at the

University. That educational background is reflected in the

full title of his earlier and less well-known book : A Theory

of Moral Sentiments, which its author considered a better

work than Wealth of Nations. The Scots university

professors debated long and hard on whether mankind was

basically selfish or basically good. This reflected the

tensions between the dogmas of Presbyterian Scotland, inherited

from John Knox, the view of the Catholic Church, and the growing

rationalism and humanism of modern thinkers. Like a good

Presbyterian, Smith saw mankind as basically selfish, but also

saw how that self-interest helped to build capitalism and drive

industry and commerce. However, the self-interest was balanced

to a degree by the need for cooperation that was brought about

by the division of labour and the inter-connectedness of

industrial society. He had little time for government

interference in the economy, which he viewed largely as

unhelpful, or worse, except however, for the protection of the

weak and vulnerable.

A full century

before Karl Marx, Smith identified the human problems resulting

from monotonous work in miserable factory situations. His pin

factory example illustrated well the mental mutilation of

workers in cramped places in the chain of production, where

there was no room for the enlargement of mind and spirit. This

merited the most serious attention of government and civic

institutions to counteract the deformity of human character

resulting from the division of labour. He did not believe as

some had avered, that society benefited from becoming entirely

‘commercial’ in its mentality and attitudes. Steps had to be

taken to correct and counter the bad effects of commerce in both

capitalist and worker alike. A major step would be public

support for schools to ensure that the benefits of a civilized

culture reached the public at large, (like the parish schools of

Scotland). Adam Smith understood that a modern capitalist

society would be committing suicide, politically and culturally,

if it failed to establish a decent system of education for all

its citizens.

Capitalists were

susceptible in his view to losing sight of the larger picture,

and to viewing life in the narrow terms of their businesses,

profits and losses. Smith believed that a free market would

help to curb the greed and power of some merchants. He had

criticized them for their inconsistency in complaining about

high costs, while saying nothing about the bad effects of their

huge profits. Smith deplored the mean rapacity and monopolizing

spirit of the greedier merchants, opining that the government of

an exclusive company of merchants is perhaps the worst of all

governments of any country. We have seen evidence of this the

past century and at present, in regimes where a handful of

businessmen have obtained either political or monopolistic

control, (or both), be they drug barons, oil barons, sugar

barons, diamond dealers, or loggers - and they have gone on to

act with brutal uncaring greed and selfishness.

|

Adam Smith, the much-quoted Scots

economist and moral-philosopher

Our view of prosperity

is strongly influenced by the barrage of messages we receive from every

form of media, that equate economic well-being with the value of shares

traded on the stock exchange, the excessive profits made shamelessly by

large corporations, rises in the gross national product, and the amount

of lending facilitated by our banking and financial institutions. By

these measures, countries like the south Pacific states, Cuba, the

Faeroe Isles, or the Maldives, may appear to be poor and insignificant,

but their people on average enjoy a better and more peaceful

environment, with enough to eat, and adequate systems of education and

health. For ordinary people, quality of life may be good when GDP is

low and can be miserable even when the GDP is high.

Our press and media regularly express disapproval of the excessive

profits made by big business, and of the obscene salaries and bonuses

that the captains of industry award to themselves at every opportunity.

Politicans wring their hands and claim to be offended by the behaviour,

- yet none of them do much about it. It has appeared to me that there

is a basic dilemma posed by their blanket acceptance of the capitalist

free-market system, and the opportuniies it gives to human greed,

corruption and weakness. Without a strong fundamental integrity in

society, the entire system encourages and rewards sheer greed. But then

we have long since ceased to teach the cardinal virtues or the seven

deadly sins in our schools. The Bible is rarely read by students unless

in a critical or myth-ridiculing spirit. And our judicial systems are

much more lenient on the white-collar criminal than they are on the

opportunist street thief or rapist. |