|

At sunset Martin Alonzo called out with great joy from his

vessel that he saw land, and demanded of the Admiral a reward for his

intelligence. When he heard him declare this, the Admiral fell on his

knees and returned thanks to God. … Those aboard the Nina ascended the

rigging, and all declared they saw land. … At two o’clock in the

morning, the land was discovered at two league’s distance. The Admiral

landed in a boat bearing the royal standard. On shore they saw trees,

very green, many streams of water, and diverse sorts of fruits. … The

people are of a good size and stature, and handsomely found. Weapons

they have none, nor are acquainted with them. They very quickly learn

such words as are spoken to them. I saw no beasts on the island, nor

any sort of animals save parrots. …

I came to the Cape

where we anchored today. This is a beautiful place. My eyes never tire

of viewing such delightful verdure, and species so new and dissimilar to

that of our country, which could be of great value as dyeing materials,

medicine and spicery. We experienced the most sweet and delightful

odour from the flowers and trees. …

Every day I have been

in these Indies, it has rained more or less. The land is verdant,

temperate, beautiful and fertile. The fish are shaped like dories,

blue, yellow, red, and every other colour. Here also are whales.

Beasts we saw none, nor any creatures on land save parrots and lizards;

but a boy told me he saw a large snake. No sheep or goats were seen.

From the journal of Christopher Columbus, 1492

The immense empire of

Brazil is divided into 20 provinces. Its situation is highly favourable

on account of the two mighty waterways, the Amazona and La Plata. These

link the sea trade with the vast interior of the continent. First

descriptions of the interior were by gold-greedy adventurers

who sought out Dorado, - the fabulous land of gold and diamonds.

Several large mines are still worked by English companies, but

agriculture is now considered to be a sounder basis of progress for the

country. The southern provinces are particularly well adapted for

cattle breeding.

Sugar cane is vital to the region, introduced by the

Portuguese in the 16th century. Pao Brazil dyewood is

exported. This is the product that gives the region its name. Tobacco

is another indigenous plant, held in high esteem by the Indian tribes.

The Pajeo or native priests besmoke their patients with big cigars –

more than 2 feet long. There is an excellent equivalent of Chinese tea

called Herva Mate or conguoha, that grows well everywhere in the

southern province. Infusions are imbibed through a delicate little tube

or bombilha. This is the indispensable national beverage of the south,

while the north has cacao or guarana instead.

Selected from : Amazonia and

Madiera Rivers,

Notebook of an

Explorer Franz Keller

1835 - 1890

“You will find here the

peaceful and generous native people who inhabited this land when the

first Europeans arrived. Most of them were annihilated by exploitation

and the enslaved work they could not resist. It has been estimated

that the conquest and colonization of this hemisphere resulted in the

death of 70 million natives, and the enslavement of 12 million

Africans. Much blood was shed, and many injustices perpetrated; a large

part of which still remain after centuries of struggle and sacrifices

under new forms of domination and exploitation.

I am mindful of your endeavours to have more justice in the

world every time I hear my homeland slandered by those who worship no

other god but gold. Slanders in history have been used to justify the

worst crimes against people,

including the recent slaughters of 6 million Jews and 4 million

Vietnamese.” [I

assumed in the 4 million Castro included civilians killed by the bombing

of Laos and the Cambodian border area. However, some of my Vietnamese

colleagues were later to inform me that 4 million is in fact, the

unofficial local estimate of casualties during the American war. It was

not possible during that conflict to count all civilian deaths.]

Dr Fidel Castro, in a speech to Pope John

Paul II, January 1998

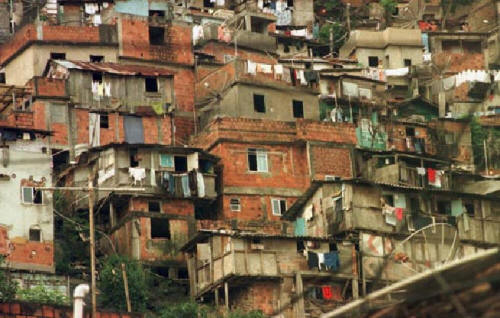

“Common

features of the primate city landscape in South America, are the

sections comprised of shanties, shacks, and makeshift huts inhabited by

those who have no other shelter. Known as barriadas in Peru,

ranchos in Venezuela, villas miserias in Argentina, or

favelas in Brazil, these squatter settlements have been estimated to

house as much as one-third of the urban population.” (Butterworth and

Chance, 1981). Mexico City has some 4 million squatters, Calcutta has

2 million, and Rio de Janeiro has over 1 million.

“In Rio

-- this was in 1948 -- there were said to be three hundred thousand

people living in favelas (urban hillside slums). Today there are nearer

a million. You come on favelas in the most unexpected places. In

Copacabana a few minutes walk from the hotels and the splendid white apartment houses and the

wellkept magnificent beaches you find a whole hillside of favelas

overlooking the lake and the Jockey Club. In the center of Rio a few

steps from the Avenida Rio Branco on the hill back of one of the most

fashionable churches you come suddenly into a tropical jungletown.”

(Dos Passos, 1963)

“They

(street children) seem to be everywhere: begging in front of

restaurants, peddling cigarettes in sidewalk cafes, shining shoes

outside the train station, washing clothes in public fountains. Take a

morning stroll on the elegant, black-and-white mosaic sidewalk that

curves along Rio's Copacabana Beach and you'll smell them; dozens sleep

under the palms there, and the beach serves as a toilet.” (Brookes,

1991)

“. .

the upper classes, and the political right-wing, in Brazil, view street

children as a blemish on the urban landscape and a reminder that all is

not well in the country. Unwanted and considered human waste, these

ubiquitous tattered, mainly black children and adolescents evoke strong

and contradictory emotions of fear, aversion, pity and anger in those

who view their neighborhood streets, boulevards and squares as 'private

places" under siege.” (Scheper-Hughes and Hoffman, 1994)

The huge continent of

South America, the islands of the Caribbean, and the region of Central

America, were all viewed as legitimate prey by the great maritime powers

of the 16th and 17th centuries. Spain was

successful in colonizing most of the region, which it did in remarkably

short time in the wake of its explorers and adventurers such as

Christopher Columbus, Amerigo Vespucci, and Hernando Cortez, who with a

few hundred soldiers, conquered and plundered the great Aztec empire.

The Portuguese followed, and also to a lesser degree, did the Dutch,

French and English. Today it is United States ecomomic and military

power that dictates what freedom and prosperity the peoples do or do not

enjoy.

Scotland once attempted

to invest in and develop a region of central America that could have

become a trading centre similar to Singapore or Hong Kong, but with

Scottish rather than English merchants controlling the business. This

was at the end of the 17th century when Scotland and England

shared a common King, but remained separate kingdoms. The venture was

known as the “Darien Scheme”, and it is sometimes dismissed as a sort of

“South Sea Bubble”. But it was nothing of the sort, and if allowed to

proceed, could have developed into a profitable enterprise with long

term political and economic benefits. Its chief founder, a man of

remarkable vision and imagination, who had founded the Bank of England,

was William Paterson of Dumfries. He envisaged a trading station on the

Isthmus of Panama, that would be a conduit for growing trade between

Europe and the Far East. Darien, he declared, would be “the door of

the seas; the key of the universe”; and affirmed the principle that

“trade will increase trade; money will beget money”. As others have

noted, it was a Panama Canal project, 200 years ahead of its

time.

Below: the Darien National Park today

Ships leaving Leith, Scotland, for Darien

(fanciful 19th century sketch)

The venture was scuppered by London merchants, chiefly those

of the East India Company, with the support of the crown. They were

terrified that their near monopoly of colonial trade with the east would

be threatened, so they pulled every string possible to deny official

recognition and support. They blocked attempts to raise capital in

London, and also on the Continent where Sir Paul Rycant, resident in

Hamburg, spied on the efforts of the Darien directors and obstructed

subscriptions to the project. The whole sorry saga is well documented

in a number of books, each with their own bias, depending on the

authors’ English or Scottish viewpoint. Spain’s hostility (encouraged

by England’s ambassador to Spain) was another major factor, as it also

wished to protect its near monopoly on trade with central and southern

America. The one friendly, supportive group the Scots had was the

Indian leaders of the Darien peninsula tribes. They included ‘captains’

Pedro, Diego, Andreas and Ambrosio.

the Darien peninsula area

Attacks by Spanish

ships on the fledgling Darien settlement were largely (but not wholly)

successful, due to a prohibition on assistance from England’s

plantations in north America, facilitated by England’s Secretary of

State, James Vernon, a man of considerable resolution and cunning. The

climate and remoteness of the Darien peninsula also added to the

difficulties faced by the settlement, though that influence has probably

been overstated as similar climate and conditions prevailed in parts of

India, West Africa, and the Malay peninsula where English trade

flourished.

The forces arrayed

against the venture resulted in the destruction of the station and the

death of many of the pioneers. England had written the script and Spain

completed the dirty work with King William’s blessing. The cream of

Scots merchants and civic leaders were involved in the Darien project.

Many knowledgeable Scots who were aware of the betrayal and

interference, wondered why they maintained an allegiance to a Dutch King

sitting on the English throne, lacking both understanding of and

sympathy with, Scotland’s aspirations. In addition to a wave of

national fervour, the Scots had poured into the scheme, all the money

the small country could spare. Among the pioneers who perished there

were two men from my locality, Alexander Kinnaird, Laird of Culbin, an

early Jacobite and his son William. Many hundreds of similar brave and

enterprising Scots died with them. Scotland was bankrupted and shown in

a most brutal way that it dare not assert an economic independence.

Forty-five years later, in even more brutal fashion, it was made clear

to Scotland that it could not assert political independence either.

Seven years after the end of Darien, the Act of Union with England was

signed, a scenario that King William and his advisers probably had in

mind all along.

William Paterson, Darien visionary, and

founder of the Bank of England

Professor Paul Scott,

in his book The Union of 1707 : Why and How, says that the Darien

affair gave the English government an added reason to seek to abolish

the Scottish Parliament which had shown it could take initiatives

damaging to English trade. England also wanted to secure its northern

border during the prolonged wars with France. By offering, or appearing

to offer the Darien shareholders some compensation, Scottish support for

the Union could be bought. On the Scots side, English hostility to

Scottish economic development, increased distrust of their powerful

southern neighbour.

Scottish involvement in the Americas thereafter became

insignificant, except for the contribution of individuals within Canada

and the United States. So Scots adventure in South America is now

pictured quaintly in Daniel Defoe’s account of the experiences of

Robinson Crusoe. The book is based on the factual experience of a

Scottish seaman from Lower Largo in Fife, Alexander Selkirk (1676 –

1721), who was voluntarily marooned on one of the islands of Juan

Fernandez 400 miles off the southern coast of what is now Chile. [There

are actually three islands in the Juan Fernandez archipelago; -

Masatierra or ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as it is now known, the only one of the

three that is inhabited; - tiny Santa Clara island; - and Masafuera or

isla ‘Alejandro Selkirk’ which is where its namesake was a castaway. It

is slightly larger than Masatierra, with an area of 50 km2 (i.e. about 6

miles by 3 miles), and has the highest point of the the 3 isles, Los

Inocentes, which rises to 1,319 metres. Ships from Chile sailing to

Easter Island, often call at the archipelago en route.]

Just four years after the end of the Darien venture, on his own

initiative, Selkirk wisely left the unseaworthy privateer ship Cinque

Ports in 1704 (which sank later). The ship was under the command of

Captain William Dampier, a noted mapmaker and greedy privateer, who was

an incompetent and irresponsible seaman. [Dampier

was later to be charged by his crew with “cowardice, brutality and

drunkenness”, and lost his office as a result. He died a pauper, in

1715.]

Selkirk’s experiences

on the island, though harsh, were not too different from the somewhat

glamourised account by Defoe. He was rescued in 1709 by another British

privateer, the Duke, having eluded capture by two Spanish ships

that called at the island. He acquired a ship of his own and

eventually made it back home, married, and later became a lieutenant in

the navy, dying at sea of fever in 1721. I read Defoe’s book with

interest as a boy, and later when serving 3 years in the Zambesi valley,

I found Cowper’s poem ‘On the Solitude of Alexander Selkirk’, to

be a remarkably accurate and poignant expression of isolation which can

also be experienced when one is in a distant land and among people of a

totally alien culture to one’s own.

Statue of Alexander Selkirk (Robinson

Crusoe) at his birthplace in Largo, Fife, Scotland

Interestingly, Brian

Keenan, in the account of his years as a hostage prisoner of Islamic

militants in Beirut, refers to a degree of comfort he drew from Defoe’s

book. While identifying with the castaway’s situation, he tried to

retell the whole story in his mind from the perspective of Man Friday

who would have regarded elements of the white man’s ideas and behaviour

as part lunatic, part comical.

Juan Fernandez Islands where Selkirk

spent 5 years

Once when we were operating on the west coast for prawns and

fish, my father was approached about the possibility of taking his

vessel to Venezuela or Guyana to engage in shrimp trawling for a U.S.

company. The enormous shrimp industry was in its infancy at that time.

A businessman who had flown across the Atlantic, had asked my father to

stay ashore and discuss the possibility for a day, so we fished under

the command of the mate that trip. During the day, as deckhands, we

joked about what it would be like to work in warm seas and off

palm-fringed beaches. As things transpired, nothing came of the idea

though my father was not opposed to it in principle. The American,

Morgan by name, chatted to us in the cabin that evening, then made his

way to Prestwick airport for the flight home. I recall that just

before we nodded off to sleep that night in our bunks, the drone of an

aircraft was heard passing high overhead. As it died away, the

engineer, with a touch of dry humour and a hint of skepticism, murmured,

“good-bye, Morgan”. As far as I recall, apart from one brief

letter, we did not hear from him again.

The first true Latin

American I came to know closely was one of the finest examples of those

colourful persons. Milton Lopez, the Chief Fisheries Officer of Costa

Rica, was a student of mine in an international class I taught for a

year in 1972 – 73. He was mature, frank, thoughtful, and perceptive.

We had many interesting discussions on the fisheries of that beautiful

central American state which has both Caribbean and Pacific coasts.

Milton also educated me on the politics and culture of the Latin

American countries and societies. After his return to Costa Rica, Lopez

was seriously injured in a car crash, and spent a long time on crutches,

but eventually made a full recovery.

A second fine friend

from the region was Hector Lupin of Argentina, who served in the Fish

Technology Division of FAO’s Fishery Department in Rome, Italy. Our

families became quite close, and we were kindly gifted with a sliver

‘maté’ tea container which we still treasure. Maté is a kind of tea

made with herbs, that is drunk by gauchos and shepherds all over the

southern grasslands of Argentina and Chile. The tea is shared

communally, and is drunk through a filter via a pipe of silver or lesser

material. Hector was a kind and gentle person, and during the Falklands

war he came to me quite concerned, and asked for reassurance that the

conflict would not become an issue between us. I was only too glad to

provide that assurance, to which he responded, “yes David, just

imagine, - General Galtieri and Mrs Thatcher, - why should we get upset

over those two awful characters” !

A third friend and

colleague from Latin America was from Chile. Ramon Buzeta had been a

supporter of Salvador Allende when a young scientist working for his

country’s fishery research organization. He told me of the brutal

treatment and torture he had to endure at the hands of Pinochet’s

ruthless police and soldiers, following the military coup that was

supported by the CIA and the US Government. Fortunately Ramon survived

and was accepted as a political asylum seeker by Norway. From there he

got work with the United Nations Agencies, and eventually with the South

China Sea Programme where we were colleagues for 2 years. The evil side

of the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet has been well

documented, and the revelations of dreadfully brutal torture by that

regime continue to shock the world. But that never discouraged

politicians like Reagan and Thatcher from treating him like a hero and

affording his regime every protection. One only has to look at the way

the World Bank shoveled hundreds of millions of dollars into Pinochet’s

Chile after it had given Allende the cold shoulder, to see how our

much-vaunted democratic institutions serve the rich and powerful at the

expense of justice for the poor.

General Augusto Pinochet of Chile

Let me relate a small

tale about Pinochet as an aside to these memories. The Chilean

Ambassador in the Philippines served his President faithfully, and would

call Ramon Buzeta from time to time, to ‘talk’. Buzeta’s dissident past

was never mentioned, but was alluded to as the Ambassador let him know

that they were keeping their eye on him, and any chance of him being

allowed to return to his homeland would depend on how the regime

regarded him. This message was conveyed politely and diplomatically,

but with the sinister smile of a bully. (As Shakespeare put it in

Hamlet, - ‘that one may smile, and smile, and be a villain’ !)

Well, to the ambassador’s delight, one of the first formal foreign trips

that was organized for Pinochet, was an official visit to the

Philippines. Plans were completed, and the Ambassador was to glow in

the reflected light of his President as he began to be recognized and

accepted on the world’s stage.

Things went oddly and

unexpectedly wrong at the last minute, as sometimes happened in the

Philippines. While Pinochet was aboard his plane flying across the

Pacific, word was received from the Philippine Foreign Ministry that the

visit was off. It was cancelled at the last moment. No satisfactory

explanation was provided, - at least not in public. So the unlucky

Ambassador had to call his President and tell him to turn his plane

round and head back to Chile with the whole delegation. The General was

furious. The ambassador was recalled immediately to report in person to

Pinochet for the events that caused him such public embarrassment.

Before flying back, the ambassador and his wife pleaded tearfully to

Ramon and Jenny for sympathy and understanding. They tried to say that

they had never been part of the brutal side of the regime, and had

always acted in good conscience and considerately of others. Well, as

history has told us repeatedly, these brutal regimes eventually consume

their own children. Those who served ogres like Stalin, and Pol Pot,

and other despots, got no consideration or mercy from them in the end.

What became of the unfortunate ambassador and his family I do not know,

but I daresay his career ended prematurely.

Ramon’s experiences

shed light on the behaviour of right wing military regimes in South and

Central America, and on United States complicity in horrific treatment

of dissidents and of peasant communities whose only crime was to seek

economic justice and a future for them and their children. A powerful

trinity once controlled many of the region’s countries. It was composed

of the military, of big business (and often of drug dealers), and right

wing politicians. It has always been a mystery to me how America has

consistently viewed such regimes with favour, while Castro’s Cuba has

been vilified for half a century.

I listened with care to the speeches made by Fidel Castro and

Pope John Paul 2, on the occasion of the Pope’s visit to the island

state in January 1998. Castro gave an eloquent description of the

suffering of his people at the hands of a dictatorial regime, and of the

failure of the Catholic Church to stand up against the injustice. The

great pope, true to his conservative instincts, was unmoved, and made no

concessions to Fidel’s case for a socialist government to right those

wrongs. John Paul 2, who truly had a genuine concern for the poor, had

no time for the liberation theology developed by priests like Gustavo

Gutierrez of Peru, Leonardo Boff of Brazil, and Juan Luis Segundo of

Uruguay, who sought to present Christ as the political liberator of

oppressed peoples.

Fidel Castro

A dear New Zealand

colleague of mine who went on to work for the ADB and the World Bank,

told me that when serving in Panama as a young volunteer, he lived with

a group of Roman Catholic priests, since suitable accommodation was

limited in the particular area. Most of the priests were of ‘liberal

theology’ persuasion. They had deep personal concern for the poverty

and injustice suffered by the local people. Some even took up arms

occasionally to assist small militias who tried to defend their

communities from the army and from the land grabbers. So, despite

opposition from the Vatican, liberation theology is still being

practiced by elements of the Catholic Church.

At the risk of trying

my readers’ patience, I will mention one more Latin American friend and

colleague. This one was from Colombia. Teresa Salazar was an

enthusiastic and imaginative development economist with the United

Nations Industrial Development Organisation located in Vienna. We

worked together on a number of integrated development programmes and

projects for fishery, agricultural and industrial sectors in Africa and

the Pacific. I mention Teresa mainly to raise the problem of the

narcotic trade in the Americas. Her brother was Minister of Justice in

Colombia for a period, and received so many death threats from the drug

barons, that he sought to prosecute, he had to send his family abroad

for their protection. Teresa described to me what it meant for any

official in her country to take a stand against the perpetrators of that

evil industry.

When one studies the

drug problem deeply, it is disturbing to learn how callously major

governments can collude with the narcotics trade mafia, and can even get

involved in the production and sale of drugs to raise money illicitly

and/or avoid problems of budgetary controls. The Central Intelligence

Agency has long been suspected of ‘being in bed’ with drug dealers, as

has parts of the FBI at times. Drug smuggling routes have been

utilized by the CIA to ship money and arms when legitimate routes were

not possible or could have been open to detection. The most glaring

example was that of Colonel Oliver North [It

would appear that Colonel North was somehow involved in the capture of

Terry Waite who was held hostage by extremist elements in Lebanon for 5

years. Waite has hinted at this betrayal, but the only public

indication was at a brief meeting after his release, when Waite declared

to North, “I wanted to say this to you in person, - I forgive you”.

No explanation, was given, but the guilty look on North’s face said

it all. The US hostage, David Jacobsen, who gave Colonel North thanks

and credit for his own release, nevertheless had serious doubts about

North’s activities and their part in Terry Waite’s abduction and

imprisonment. These are expressed in his book, My Life as a Hostage.]

who sold weapons to Iran to get funds for ‘contras’ fighting the

democratically elected government of Nicaragua. Though Congress had

expressly forbidden aid to contras, (and sale of weapons to Iran), this

activity was undertaken with the encouragement of William Casey, then

Head of the CIA, and (unless we are totally naïve), with President

Reagan fully aware but clinging to ‘deniability’ as willful ignorance is

sometimes termed.

The CIA and the contras

also collaborated with mafia elements and drug traders to increase their

power and income. Similarly the IRA in Northern Ireland, financed much

of its murderous work with drug money, as to a lesser extent did some of

the loyalist paramilitaries. My Thai friends who lived through the

period of the Vietnam war, including some who worked in intelligence

gathering, tell me that the U.S. military was deeply involved with the

war lords of the “golden triangle”, both for strategic advantages, and

to tap sources of finance that did not have to be reported, and could

not be traced.

To be fair, not only

western security services and military have used the drug trade for

their own purposes. Bulgaria was for some time involved in the

international narcotic trade. President Todor Zhivkov’s state security

organization, the KDS, was a leading player in the black market for the

deadly white powder. They used two front organizations through which

the trade was conducted, first Kintex, then later Globus. President

Zhikov was challenged directly about the illegal business by that

strange post-war figure from the world of press, trade and politics in

East Europe, Britain and Israel, - Robert Maxwell.

The removal of

President Manuel Noriega of Panama by the USA through a mini invasion

had other elements to it than his involvement in drugs. Apparently he

had always been part of that business, yet was on the CIA payroll and

was entertained in Washington by the then CIA Head, George Bush senior.

Noriega fell out of favour for other reasons. A US Government web site

states that he ‘was going to become a dictator’ ! Well, that was rarely

a problem to the US in Latin America, Africa or Asia. The real reasons

for Noriega’s removal have been kept quiet. But he was replaced by a

more pliant government leader on 20th December 1989 who

permitted continued US influence over the territory. David Harris, in

his 2001 book Shooting the Moon, declared that Noriega was the

only one of all the rulers, dictators, warlords and juntas around the

world, that the USA in 225 years went after with an unprovoked

invasion. The President was taken to America for trial and imprisonment

for violations of U.S. law committed on his own native turf.

Had that military

operation been directed against a country where the government had

committed mass murder, torture, or serious human rights crimes, like

Pinochet’s Chile, Sroessner’s Paraguay, Somosa’s Nicaragua, Papa Doc’s

Haiti, or D’Aubuisson’s El Salvador, the world might have understood,

but Panama was guilty of none of that. It simply dared to defy the

demands of a handful of corporate executives, and powerful politicians.

Panama had insisted that the Canal Treaty be honoured. It had also

explored the possibility of building a new canal with Japanese finance

and engineering expertise. Yet for these efforts of national sovereign

policy it was to be invaded and taken over.

From a U.S. perspective

the invasion of Panama, and CIA interference in South American states,

is based on the Monroe Doctrine declared by President James Monroe in

1823. This defined America’s “Manifest Destiny” which asserted that the

United States had special rights over all the hemisphere. It has been

used as justification of the displacement of the Red Indian peoples and

the theft of their tribal lands, as well as the invasion of several of

the USA’s southern neighbour countries. Admittedly, Noriega was guilty

of many things, as was Saddam Hussein in more recent times, but neither

was a threat to America. Noriega’s predecessor, General Omar Torrijos

Herrera, who was a committed pro-poor reforming President, was killed in

a plane crash in 1981. The novelist Graham Greene claims that a bomb

had been planted in the plane.

It was Milton Lopez who

first drew my attention to an underlying identity problem that explains

some aspects of the behaviour of his people who are mostly of mixed

descent. There is something in the psyche of Latin Americans, opined

Lopez, that makes them want to be like their conquistador father, and

that despises their Indian mother. A colleague of his, attending the

same college course, Luis Cuciero from Urugauy, put the racial tensions

more bluntly, for the societies of the east coast of South America. He

described a kind of social caste system based on colour, he said; with

people of whitest skin being most highly regarded, and conversely with

black skinned persons. Neither Milton nor Luis displayed any prejudice

whatsoever, I hasten to add, and they mixed well with the students we

had from Africa. The same was true for the one black member of the

class from South America, the Director of Fisheries from Trinidad, who

was a most cheerful and sociable addition to our interesting group.

I was to make two trips

to Mexico, the first in 1966 and the second in 1978. Later, in 1998, I

went to Bolivia for a month, and it is from those two countries only

that I have direct personal impressions of that huge continent and its

dear people.

Mexico covers an area of nearly 2 million square kilometers,

and has long marine coasts on both the Caribbean (Gulf of Mexico) and

the Pacific. It borders the United States to the north, and both Belize

and Guatemala to the south. It had a Mayan civilization for centuries,

from around 550 to 950 AD. The Mayans built the many large pyramids

that remain today in the Yucatan peninsula. The Aztec empire ruled the

region from the 14th century, its most famous king being

Montezuma II, 1502 -1520. The Aztec empire and civilization was ended

abruptly by Herman Cortez and his 700 men in 1519 – 1521.

Map of Central America

Maya pyramid, Yucatan, Mexico

The country remained under Spain till it achieved

independence in 1810. At that time much of what is now Texas, was held

by Mexico. This included the Spanish mission of San Antonio de Valero,

a Catholic station from 1724 to 1793 when it was secularized. The

Spanish military took it over and called it Alamo (cottonwood) after

their home town Alamo de Parras. From 1800 to 1810 the fort was

variously occupied by Spanish, rebel and Mexican soldiers. Mexico had

permitted Americans to settle in Texas and to own land, provided they

became Catholic. But such immigration was stopped in 1830. In 1835 the

Alamo was taken over by a group of Texan volunteers led by Ben Milam.

They were then besieged in February 1836 by General Antonio Lopez with a

large force of Santa Anna’s army. Within a month the 200 defenders were

overwhelmed. Among those who died in the siege were the commander

William Travis, and the frontiersmen, Davey Crocket and Jim Bowie.

America was to recover the Alamo and take possession of the area later,

finally incorporating Texas into the United States in 1870.

Port of Vera Cruz, Mexico

California was also

part of Mexico for a period. It had been visited and tentatively

explored by Spaniards from the 16th century. During the 18th

century a large number of Catholic missions were established. Following

Mexico’s independence from Spain, California (named after a mystical

Queen Califia of the Amazons), became a province of Mexico and remained

so for 25 years from 1821 to 1846. A fascinating glimpse of California

when a part of Mexico is found in Two Years Before the Mast, the

factual record of Richard Henry Dana’s voyage to that coast, in the

Boston brig Pilgrim, 1834. The Pilgrim collected a

cargo of dried cow hides from trading stations that later became

Monteray, San Pedro, San Diego, Santa Barbara and Santa Clara. Dana

sailed back to Boston in 1836 on another ship, and wrote his book

shortly after. Control of California passed to the U.S. following the

American – Mexican war of 1846 – 1848. The gold rush of 1848-49 added

to the urgency of formalizing U.S. rule, so in 1850 it became the 31st

State of the Union.

Richard Henry Dana, author of Two Years Before the Mast

From 1864 Mexico was

briefly under French domination, the ‘emperor’ Maximilian [Ferdinand

Maximilian, although appointed by the French Emperor Napoleon III, was

actually an Austrian Archduke, and brother of the last great Emperor of

Austro-Hungary, Francis Joseph, or Franz Josef. Maximilian was well

meaning but naïve, with all the limited vision of European aristocracy.

Tragically his life was ended by firing squad in 1867.] seeking to establish and maintain control of the

territory. This was ended by the great Don Benito Juarez who became

President in 1867. He is known as ‘Mexico’s Lincoln’, and though the

two never met, they held each other in high regard. Of pure Indian

stock, Juarez was educated at a Franciscan seminary. But preferring law

to religion, he graduated in that field in 1834, and became a champion

of workers’ and Indians’ rights. He became active politically and

helped to overthrow the despotic and incompetent Santa Anna. He served

as Governor of Oaxaca until his organization of resistance to Emperor

Maximilian, after whose ouster, he became President of Mexico. He died

in 1872.

Mexico suffered a

violent social revolution from 1910 to 1917 when a new constitution was

drafted and accepted. The revolution, led by colourful but tough

characters like Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa, involved much

bloodshed. It is believed to this day that the memory of that

revolution remains a restraint on the excesses of the wealthy, the

politicians, and the military in Mexico.

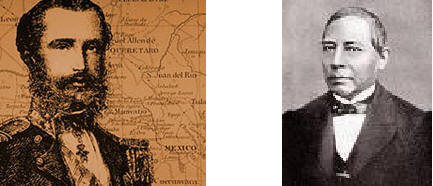

Emperor Maximilian, a tragic imposition

on Mexico by France and the Austro-Hungarian empire, and on the right, -

Don Benito Juarez, President of Mexico

who refused to accept the colonial master from Europe.

My first visit to that

fascinating country was to the Gulf ports of Vera Cruz and Alvarado. I

was making a study tour in the summer of 1968, of the shrimp industry in

the southern US States and Mexico. It is probably different now, but I

recall stopping over in Houston, Texas to get a visa. The taxi ride

into Houston and back to the airport, cost me more than I had to pay for

all my meals and hotel rooms in Mexico ! Vera Cruz was then a rural

town that conformed to many of our Hollywood caricatures of the

country. A few miles up the coast lay the beautiful new pilot port of

Alvarado, which was most impressive. But the flight from the capital

city to the coast and back, was a hair-raising experience as the old

Douglas DC-3 aircraft flew up and down the escarpment in the middle of a

thunderstorm.

Mexico had two main

fisheries to prosecute. One was the shrimp trawl fishery in the Gulf,

and the other was the oceanic tuna fishery in the Pacific. The latter

was a source of friction between Mexico and the USA for many years.

When the UN Law of the Sea of 1972, authorized each sovereign state to

claim fishing rights over an EEZ zone extending 200 miles to sea, Mexico

and most other maritime nations did so. But the USA for long opposed

that element of international law and refused to sign up to UNCLOS [The

UNCLOS law of the sea establishing 200 mile EEZs, was passed in 1982,

and most maritime states signed up to it within a very short time. The

USA was one of the few that held back. President Clinton signed the

agreement in 1994, but the Senate failed to pass it due to opposition by

some Republican Senators.]

as it was called, largely due to pressure from America’s powerful tuna

industry based in San Diego, California. This resulted in several

confrontations at sea between US tuna boats and the Mexican navy. In

the end it was the US tuna industry that lost out. It was dealt a death

blow, not by the Mexican navy, but by school kids in the States who

advised their mothers to buy only those cans of tuna that had “dolphin

safe” labels. As the San Diego fleet was a major culprit in the capture

and death of dolphins in its purse seine nets, it was the tuna it

produced that was effectively boycotted on the market.

The shrimp industry

which was the focus of my first visit, had developed into a major income

earner as shrimp became an extremely popular food dish. Although shrimp

boats took considerable quantities of fish, most of it was then dumped

over the side. Al the freezing capacity and refrigerated storage on the

trawlers was needed for the more valuable shrimp. As an American shrimp

trawlerman told me “we long ago got out of the fish business and are

now in the dollar business”.

All over the world,

shrimp trawl fleets pose a problem because of the ‘discards’, the fish

dumped overboard, which amount in volume to about 2 to 3 times the

weight of shrimp landed. Dayton Lee Alverson who I met in 1969 when he

headed the US BCF / NMFS Pacific Fishery Office in Seattle, later made a

study of the global extent of fish discards, together with J.G.Pope of

lowestoft, and others, and found it to amount to, on average, 27 million

tons of fish each year. This represents a huge financial and resource

loss, and involves a considerable negative impact on the marine

environment. To date, no satisfactory solution has been accepted or

implemented to end the practice of discarding, although I and many other

fishery specialists have proposed a number of actions.

The second visit, 11

years later, took me to the plush surrounds of Cancun on the south-east

coast, for the Latin American Fisheries Symposium. I was there at the

invitation of the Mexican Government and was given a seat at the

conference next to the Minister of Fisheries from China. There was

considerable resistance at the conference to the neo-colonial attitudes

of Spain, France, Britain and the USA who felt they had a right to

muscle in on the continent’s fish resource, and to dominate in matters

of equipment and technology choice. Opposition was also growing to the

fish meal industry which was supported by Norwegian investments [Norwegian

interest in fish meal production in South America, has related mainly to

the enormous stock of anchovy found off Peru, and which has been the

world’s main source of fish meal and fish oil for the past 50 years and

more. One of the Kon Tiki (1947) expedition members, Herman Watzinger,

stayed on in Peru to manage a fish meal operation for a period. I

worked for him later after he became FAO’s Director of Fisheries.]. My paper advocated national control of national EEZ

waters, development and protection of small scale fisheries, reductions

in industrial fishing, and investment in less energy-expensive and less

capital-expensive systems.

Though opposed by

delegates from France and Britain, my suggestions were all accepted by

the conference, led by Peru, the chair country of that session. I was

surprised by the attitudes of the western country representatives at

that conference. Spain behaved as if it was still in colonial power

over Latin America, and the Scandinavian fish meal industry

representatives were totally unaware of the resentment directed at that

hungry monster that consumed millions of tons of otherwise edible and

nutritious fish. Neither Europe nor the USA showed any understanding of

the poorer countries’ need for appropriate technology and less energy

expensive systems. I had earlier warned the young professionals among

the Mexican conveners that my paper would be somewhat radical. They

smiled, and declared that I was not even half as radical as they were!

My visit to Bolivia

came us a surprise. Though welcoming the opportunity to work in that

magnificent land-locked country extending from the high Andes mountains

down to the Amazon valley, I had never regarded it as a ‘fishing’

country. But Bolivia has extensive wild fisheries and fish farming, in

Lake Titicaca, in the waters of the central plateau, and in the many

tributary rivers of the great Amazon. Bolivia borders Brazil to the

north-east, Peru to the north-west, and Chile, Paraguay and Argentina to

the south.

Much of Bolivia’s

history is rather sad and violent. It broke with Spain in 1825, under

Simon Solivar, but over the next 170 years suffered some 200 coups and

counter coups. For much of that period the country was ruled by

dictatorial right wing military regimes. Some of the leaders displayed

a remarkable degree of stupidity and incompetence. As a consequence,

through ill-managed conflicts with its neighbours, Bolivia lost huge

chunks of its territory to Chile, Brazil and Paraguay. I was fortunate

to arrive in the country during the start of its current phase of more

democratic and socially responsible government.

Lake Titicaca in the Andes between Peru

and Bolivia

The highland region

around Titicaca, is populated mainly by Indian peoples with their

distinctive dress and their use of llamas and donkeys. It resembles the

highlands of Scotland, being somewhat bleak, cold and rainy, and in its

main starch crop, potato, of which there are scores of varieties, many

of which Europeans have neither seen nor tasted. The local housing is

poor, often of mud brick, and resembling the poor houses of the west of

Scotland and Ireland in the last century. The climate on the Altiplano

is mostly cold and wet. Towering above are the snow-capped Andes

mountains, but due to global warming, much of their ice cap is melting,

perhaps never to be restored in our lifetime.

People and boats by Titicaca lake

With street vendors in La Paz

Altitude sickness can be experienced on the high plateau or

anywhere above 12,000 to 15,000 feet (3,600 to 4,500 metres). I was

surprised that Bolivians also suffered from it. A party from the Amazon

basin we took to a short course at the aquaculture research centre on

lake Titicaca, was affected. Symptoms varied from light-headedness and

headaches, to shortage of breath and stomach upsets. The normal cure

there is a brew of the herbal tea, maté de coca, which contains a bit of

coca leaf. I found it to be surprisingly effective. The capital city,

La Paz, the highest capital in the world, has a magnificent location,

and is an attractive, friendly place to reside in. The people are

friendly and helpful, with for the most part, a simple, honest, peasant

attitude to life. Whether in the market, the cafes, or the shops, one

is impressed by the basic honesty of the people who insist on giving you

the correct price and the precise change, for the transaction. The

students and young professionals I met, were eager to contribute to

their country’s development, and most helpful to me as a foreign

consultant.

With a much smaller population, and few big cities, Bolivia

has less of the social problems that bedevil the larger countries like

Brazil and Argentina. The indian peoples of the high plateau are mostly

poor and have to struggle against the elements to survive in those

altitudes. The more fertile lowlands are heavily wooded but suffer from

excessive logging and cattle ranching which may not be the ideal form of

land use there.

Down in the Amazon valley, there is an extensive network of

tributary rivers which support travel and communications, and a

substantial fishery. The surrounding land is used for cattle ranching,

cereal crops and forestry. Like much of the Amazon valley, the region

is under threat from excessive logging, inappropriate or unsustainable

agriculture, and competition for use and control of water resources.

But the Bolivian people are well aware of these dangers, and are seeking

to find ways of ensuring sustainable development. I was impressed by

the private University, Instituto de Estudios Amazonicos de Riberalta

led by its founder and President, Said Zeitum Lopez, that was designing

its whole curriculum and research programmes on the theme of long term

sustainability and social equity in resource utilization.

|

Che Guevara

Although he was

born in Argentina, and came to prominence in Cuba, the political

figure that is best known in Bolivia, is that of Ernesto ‘Che’

Guevara. He is admired or disliked depending on ones political

perspective, but when I was there, his picture adorned the walls

of the city and the University, and the Tee shirts of many of

the students. Following the end of military rule, the people

openly embraced Guevara’s memory, partly I guess as an

expression of new-found political freedom, and partly as a sign

of their desire for social justice. Surprisingly Che was in

Bolivia for just two brief periods, 1952, and 1966 – 67, when he

attempted to organize and lead communist guerillas there. His

short life ended there at the early age of 39.

Born in 1928 in

Argentina, of mixed Spanish and Irish stock (his great

grandfather was a Patrick Lynch from Ireland), he graduated as a

doctor in Buenos Aires in 1953. As a student he traveled around

the region on motorcycle, and saw first hand the hardships of

poor peasants under regimes that cared chiefly for the powerful

and the landowners. He became active in Marxist groups in the

continent, and was briefly in Bolivia supporting agitators there

in 1952. In Guatemala the following year he assisted the

leftist government of Jacobo Arbenz.

It was in Mexico

in 1954, where Che first met Fidel Castro who was trying to

organize the overthrow of the Cuban Dictator, Fulgencio

Batista. He joined Fidel’s ill-organised rebels, who sailed to

Cuba from Vera Cruz, and started the uprising in 1956. Despite

a near disastrous beginning, the revolution finally succeeded in

1959 when Batista was overthrown and Castro became President.

Guevara was

first appointed to the Cuban National Bank in 1959, and became

Minister for Industry in 1961. He gradually became

disillusioned with Soviet Communism, and his criticism of Soviet

bureaucracy distanced him from Fidel. In 1965 he left Cuba to

work with the short-lived Lumumbu government in the Congo. He

openly criticized the Soviet Union then, and embraced the

Chinese version of Marxism. While in the Congo he was assisted

briefly by Laurent Kabila, whom he considered insignificant, but

of whom the world was to hear more, some 30 years later.

In 1966 Guevara

moved back to Latin America to start a revolution in Bolivia.

The effort was short-lived and probably doomed from the start

due to opposition from both the USA and the Soviet Union. In

Cuba the following year Kosygin criticized Che before Castro for

working against legitimate communist parties. By ‘legitimate’

Kosygin meant pro-Moscow parties. This explains why the

Bolivian Communist Party gave no support to Guevara. President

Rene Barrientos, with CIA support, ordered the army to hunt him

down. His ragged band of guerrillas were located near La

Higuera at Alto Seco and Valle Serrano where he was eventually

captured and shot by government soldiers, and his remains

dismembered. His death was a bit of a mystery for some years,

but his body was eventually found in Vallegrande. He was buried

with honours in Cuba in Santa Clara, Las Villas, the location of

a battle he led and won against Batista’s forces.

Che’s fame grew

after his death, with his image achieving iconic stature among

leftist student groups. Gradually as Bolivians came to enjoy

some political freedom, he came to be regarded by the public

there as a national hero. In hindsight, despite his courage

and idealism, Guevara was a prisoner of a Marxist ideology that

could never have worked. Today, apart from brave little Cuba,

and perhaps emerging Venezuela, there is no socialist regime in

all of Latin America.

Che Guevarra, the

ill-fated Latin revolutionary

Flying over

Bolivia from Sucre to Santa Cruz, we passed over Vallegrande

where Guevara was killed. My young colleagues from the

University pointed out the area to me, and spoke of Che with a

degree of admiration and sympathy. No doubt they each had

family members of past generations, who had suffered injustices

under the various dictators.

The

romancing

of Che Guevara’s memory was to continue in some unusual ways. A

photograph taken by Alberto Korda in 1961, and numerous black

and white impressions of the same, acquired iconic status and

was widely used to decorate T-shirts and posters for many

years. When Andrew Lloyd Webber produced his famous musical,

Evita, he wrote Guevara into the script as the narrator,

though Che had had next to no contact with the woman.

|

Today the great

continent of South America and the region of Central America, faces many

problems. The aspirations of the rural poor are still being trampled on

by the rich and powerful, in the form of the logging companies, the oil

corporations, the drug barons, and the right wing militias. The urban

poor face dangers and difficulties no less severe. And there is one

group in the urban poor that merit special concern. I refer to the

thousands of homeless or unsupervised children left to struggle for

survival in the streets of Buenos Aires, Rio De Janiero, Bogota, and

other cities of the region. Although I have had no direct contact with

street kids, I have a number of friends who have worked hard to bring

them some relief, care, food and medical help, in Latin America and

elsewhere. We will consider their plight briefly as we complete our

impressions of that part of the world. Street Children [The

term "street children" was first used by Henry Mayhew in 1851 when

writing London Labour and the London Poor, although it

came into general use only after the United Nations year of

the child in 1979. Before this street children were referred

to as homeless, abandoned, or runaways.]

are an urban problem which has its roots in rural poverty, neglect and

the enforced, even violent displacement of large numbers of people from

the land. This problem is accentuated by the fact that the urban

population is becoming younger. By the year 2020 there may be 300

million urban minors in Latin cities, 30% of whom will be extremely

poor. 78% of the Brazilian population live in cities and towns. The

persistent poverty, rapid industrialisation and the burgeoning of urban

shanty towns (favelas), generate massive social and economic upheaval.

Profound poverty means family disintegration, violence and break-up

become more prevalent. Unemployment rose by 7.6% in the month to January

2000, the largest increase since 1984. Brazil is the fifth largest

country in the world with a population of approximately 166 million

people. The disparity between the rich and the poor in Brazilian society

is one of the largest in the world. The richest 1% of Brazil's

population control 50% of its income. The poorest 50% of society have to

live on just 10% of the country's wealth. It is small wonder then that

Brazil may have the world’s largest population of street people, - up to

8 million children and young persons.

The

term street children refers to children for whom the street more

than their family has become their real home. It includes children who

might not necessarily be homeless or without families, but who live in

situations where there is no protection, supervision, or direction from

responsible adults. While street children receive national and

international public attention, that attention has been focused largely

on the social, economic and health problems of the children -- poverty,

lack of education, AIDS, prostitution, and substance abuse. Street

children also make up a large proportion of the children who enter

criminal justice systems and are committed finally to correctional

institutions (prisons) that are euphemistically called schools, often

without due process. Few advocates speak up for these children, and few

street children have family members or concerned individuals willing and

able to intervene on their behalf.

An urban slum in Rio de

Janiero

Published research

indicates that compared with home based children, street based children

are less likely to come from a home headed by their father

and less likely to have access to running water or toilet

facilities; their parents are more likely to be unemployed,

illiterate, less cooperative, and less mutually caring with

higher levels of violence. Nevertheless, it should be borne

in mind that most children from poor and dysfunctional families remain

at home. Similarly, as I have always noticed in S.E. Asia, despite the

many hundreds of girls from poor backgrounds who end up in the vile

prostitution trade, there are millions of young women from

poverty-stricken backgrounds, who never resort to that immoral and

soul-destroying way of life.

|

Death and Violence on the Streets

Human Rights Watch has reported that police violence against

street children is pervasive, and impunity is the norm. The

failure of law enforcement bodies to promptly and effectively

investigate and prosecute cases of abuse against street children

allows the violence to continue. Establishing police

accountability is further hampered by the fact that street

children often have no recourse but to complain directly to

police about police abuses. The threat of police reprisals

against them serves as a serious deterrent to any child coming

forward to testify or make a complaint against an officer. In

Guatemala, where the organization Casa Alianza has been

particularly active and has filed approximately 300 criminal

complaints on behalf of street children, only a handful have

resulted in prosecutions. Clearly, even where there are

advocates willing and able to assist street children in seeking

justice, police accountability and an end to the abuses will not

be achieved without the commitment of governments.

In Latin America many people in the judiciary,

the police, the media, business, and society at large believe

that street children are a group of irredeemable

delinquents who represent a moral threat to a

civilised society a

threat that must be exorcised. The most frightening

manifestation of this view is the emergence of "death

squads": self proclaimed vigilantes, many of whom are

involved with security firms and the police and seek to solve

the problem by elimination. a

threat that must be exorcised. The most frightening

manifestation of this view is the emergence of "death

squads": self proclaimed vigilantes, many of whom are

involved with security firms and the police and seek to solve

the problem by elimination.

In Brazil, a pioneering study set up by the

National Movement of Street Children recorded 457 murders of

street children between March and August 1989. The

state juvenile court recently reported that an

average of three street children are killed every day

in the state of Rio de Janeiro. On 23 July 1993 a vigilante

group openly fired on a group of 50 street children

sleeping in the Candelaria district of Rio de

Janeiro. Seven children and one adult were killed and

many others injured. Of the eight defendants

originally accused, just two have been imprisoned; a further two

have been tried and released. Amnesty International has

estimated that 90% of the killings of children in

Brazil go unpunished.

Backed by

citizen groups and commercial establishments, death squads have

become more and more violent in their goal to "clean-up" the

streets and "guarantee public safety". It is estimated by child

care agencies that up to 5 or 6 children a day are assassinated

on Rio's streets. Children have been executed and some

mutilated almost beyond recognition.

4,611 Street

Children were murdered between 1988-1990. In 1993, eight

children and adolescents were killed in a shooting near the

Candeleria church in Rio. Between 1993-96 juvenile court

statistics showed over 3 000 11 to 17 year olds met with

violent deaths in Rio. The majority believed to have been

murdered by death squads, the police or other types of gangs. In

Sao Paulo, for example, 20% of homicides committed by the police

were against minors in the first months of 1999. The Rio de

Janeiro State Legislature found that drug gangs now account for

roughly half the child murders in Rio. The death squads have

been met with little opposition from ordinary people who feel

threatened by gangs of children. The police also fear the

children who are becoming knowledgeable witnesses to their own

criminal activities in the drug and prostitution business. |

Street children in Brazil

Current efforts [Most

of the information in this section, and the preceding two pages, is

taken from internet web sites on the issue of street children, the

phenomena, the causes, the needs, and the different means used to

address the problem.]

to address the plight of street children:

The correctional

approach views street children as a matter for juvenile justice

organizations. This correctional vision seems to dominate the thinking

of much of the public and criminal justice authorities. The result is

that thousands of street children are housed in institutions. In Brazil,

the National Foundation for Child Welfare operates twenty treatment

centers and "reform" schools for abandoned and delinquent youth.

Conditions in these facilities have been described as both crowded and

abusive. However, some changes appear to be underway, involving the

substitution of correctional initiatives with community-based treatment

alternatives.

The rehabilitative

approach has been gaining momentum throughout Latin America. This

perspective holds that street children are not delinquents as much as

they are victims of poverty, child abuse and neglect, and untenable

living conditions. Because street children are seen as having been

harmed by their environments, hundreds of church and voluntary programs

have been organized in their behalf. These typically provide housing,

drug detoxification, education, and/or work programs. The programs

benefit a limited number of youths, but are unable to address the needs

of the millions of boys and girls who continue to call the streets their

home.

Because the

institutional capacities and resources of virtually all programs are

limited and unable to accommodate the overwhelming majority street

children, services are also provided through a variety of outreach

strategies. In São Paulo, for example, the Catholic Church supports

young lay workers who provide educational, counseling, and advocacy

services to children in a street setting. In addition to teaching basic

hygiene, literacy, and business skills, the general program approach is

to instill self-reliance and empowerment so that children will find

solutions to their problems.

The preventive

approach attempts to address the fundamental and underlying problem

of childhood poverty. In this regard, UNICEF is conducting educational

campaigns to alert policy makers to the causes of children moving to the

streets. In addition to policy advocacy, UNICEF provides technical

assistance and support for promising local efforts. Those receiving

UNICEF's focused attention are of two types: 1) programs which provide

daytime activities, schooling, jobs, and other alternatives to street

work for high risk children; and 2) efforts focusing on the prevention

of family disintegration--cooperative day care centers, family planning

clinics, small business services, and community kitchens.

The

most comprehensive effort on behalf of Brazilian street youth is the

National Movement for Street Children (MNMMR), a nationwide coalition of

street children and adult educators founded in 1985 (Raphael and Berkman,

1992). MNMMR initiatives focus on shifting the management of street

children away from the criminal justice system, codifying the rights of

children into law, and structuring innovative approaches for providing

education and training for youths directly on the streets where they

live. MNMMR projects are targeting an estimated 80,000 youths, the great

majority of whom work on the city streets and live in nearby favelas,

with the remainder are actually living on the streets. |