|

Here, where my fresh-turned furrows run,

And

the deep soil glistens red,

I will repair the wrong that was done

To the living and the dead.

Here, where the senseless bullet fell,

And the barren shrapnel burst,

I will plant a tree, I will dig a well,

Against the heat and the thirst.

Here, in a large and sunlit land,

Where no wrong bites

to the bone,

I will lay my hand in my neighbour’s hand,

And together we will atone

For the set folly and the red breach

And the black waste of it all;

Giving and taking counsel each

Over the cattle-kraal.

Here, in the waves and troughs of the plains,

Where the healing stillness lies,

And the vast benignant sky restrains

And the long days make wise –

Bless to our use the rain and the sun

And the blind seed in its bed,

That we may repair the wrong that was done

To the living and the dead !

Rudyard Kipling The Settler

(South African War ended, May 1902)

Saturday mornings as a

young boy I would often join friends at the local cinema

matinee for an admission cost of 3 or 4 old pennies. The

programme was usually a Western movie or adventure film. Very popular

were the Tarzan and Jungle Jim films, invariably

featuring former Olympic swimmer Johnny Weismuller. These gave me my

first impressions of Africa, (though they were probably all filmed in

the USA), and later reading the books of Scottish explorers and

missionaries like Mungo Park and David Livingstone, I compiled the

common romantic view of the region. Harsh realities of another side to

the dark continent were glimpsed years later in what we

heard about the Mau Mau rebels

in Kenya, and the Apartheid regime in South Africa.

Our

local Laird, Captain James Brander Dunbar of Pitgaveny, (b.1875,

d.1969), was a colourful character, and an old Africa hand. I believe

his father of the same name and title was the model for John Buchan’s

fictional character ‘John Macnab’. I spent an afternoon with

him in 1965 when on a brief home leave and at his request our U.F.

church minister Mr Adamson, brought me to his house which was a

veritable museum of African artifacts. Captain Dunbar wore a kilt most

of the time, and feuded regularly with local councils when he reckoned

they stepped on his realm of authority. Sixty years after he served in

the Boer war, he could still recall Bantu and Bushman words with

accuracy.

Beside the ungathered

rice he lay, his sickle in his hand,

His breast was bare, his

matted hair, lay buried in the sand,

Again in the mist and shadow of sleep, he saw his native land. …

He did not feel the driver’s whip, or the burning heat of day,

For death had illumined the land of sleep, and his lifeless body lay, -

A worn-out fetter, that the soul had broken and thrown away.

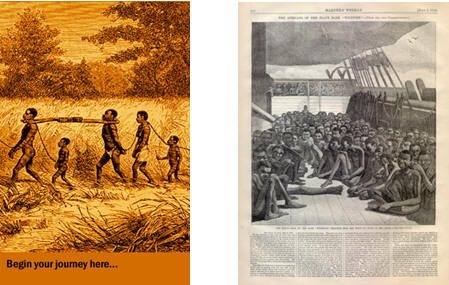

map of West Africa

The history of the

horrific slave trade of the 18th and 19th

centuries, is a shameful blot on the characters of the nations

involved. One is surprised that it took so long to eradicate that

evil. It is salutary to note the arguments made in support of slavery.

They were mainly economic, but also military and even religious.

Similar arguments are put forward today in defence of torture,

prostitution, imprisonment without trial, use of land mines and cluster

bombs, and illegal invasions or interference in the affairs of other

sovereign states. We condemn the evils of the past, but are often blind

to those of the present.

drawing of a

slave march African slave ship

|

The great

campaigner against slavery

William Wilberforce, more than

any other person in Britain, Europe or America, brought the

iniquitous slave trade to an end, by his tireless and life-long

efforts. A devout Christian, and Member of Parliament, he

declined high office and remained independent all his life so he

could more effectively expose the evils of slavery and promote

the abolition. Supported by senior politicians like William

Pitt the Younger, inspired by prominent Christians like John

Newton and the members of the ‘Clapham sect’, and opposed by the

most of the Royalty and the merchants involved in the

West Indies

trade, Wilberforce worked tirelessly to achieve legislation

ending the slave trade in 1807, and

abolition

of slavery in the year of his death in 1833.

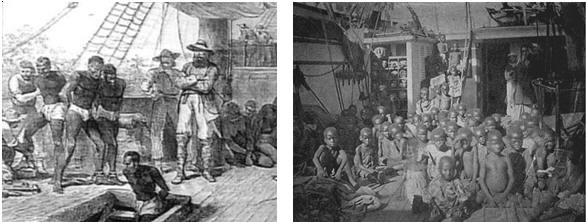

The men were

all put in irons, two and two shackled together, to prevent

their mutiny or swimming ashore. The Negroes are so willful and

loth to leave their own country, that they have often leap’d out

of canoes, boat and ship, into the sea, and kept under water

until they were drowned to avoid being taken up … they having a

more dreadful apprehension of Barbados than we have of hell

Captain H. Thomas, “The Slave Trade - 1440 – 1870”.

The stench of the hold (of the

slave ship), while we were on the coast, was so intolerably

loathsome, that it was dangerous to remain there for any time …

now that the whole ship’s cargo were confined together, it

became absolutely pestilential. The closeness of the place, and

the heat of

the climate,

added to the number on

the ship,

being so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself,

almost suffocated us. This produced copious perspirations, so

that the air soon became unfit to breathe, from a variety of

loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of

which many died … The shrieks of the women , and the groans of

the dying, rendered it a scene of horror almost inconceivable.

from “The

Interesting Narrative of the Life of (former slave) Olaudah

Equiano” 1789

The slaves are stowed so close,

that there is not room to tread among them. … For the sake of

exercise, these miserable wretches, loaded with chains,

oppressed with disease, - are forced to dance by the terror of

the lash,

and sometimes by its use. … Such enormities as these, having

once come within my knowledge, I should not have been faithful

to my senses or reason, if I had shrunk from attempting the

abolition…. I could not help distrusting the arguments of those,

who insisted that the plundering of Africa was necessary for the

cultivation of the West Indies. I could not believe that the

same Being who forbids rapine and bloodshed, had made rapine and

bloodshed necessary to the well-being of any part of His

universe. from

Wilberforce’s speeches to Parliament, 1789

Africa,

Africa, your sufferings have been the theme that has arrested

and engages my heart – your sufferings no tongue can express; no

language impart. … The restoration of these poor distressed

people to their rights, is nearest to my heart. We were once

as obscure as the nations of the earth, as savage in our

manners, as debased in our morals, as degraded in our

understandings, as these unhappy Africans are at present. … Had

other nations applied to Great Britain the reasoning which some

(here) apply to Africa, ages might have passed without our

emerging from barbarism. … God forbid that we should any longer

subject Africa to the same scourge, and preclude the light of

knowledge, which has reached every other quarter of the globe,

from having access to her coasts!from Wilberforce’s speeches to

Parliament, 1792

(Most of the above is drawn from

William Hague’s splendid biography of William Wilberforce, the

life of the great anti-slave trade campaigner, Harper Collins,

London, 2007.) |

on board a slave ship, -

drawing actual photograph of a slave ship

I worked in several

West African countries in the 1990’s. Some, like Togo and Benin, were

beset with corruption and rotten rulers whose rotund bodies and greedy

eyes gazed from portraits in every public office. They were usually

pictured in uniform, bedecked with medals of doubtful meaning or

origin. Their fancy limousines would be preceded by a score or more of

motor-cycle policemen, and all other vehicles had to drive off the road

as the President’s vehicle approached. In some African countries, any

one who dared to walk past the ruler’s palace gates after dark would be

shot before any questions were asked. The corruption went down the line

with every official grabbing all he could. My heart went out to

idealistic fishery staff members in a francophone country whose

miserable salaries were taxed by their boss to augment his.

Canoes and catches on West African

beaches

Over in Freetown,

Sierra Leone, before the civil war there, those poor but delightful

people suffered under a government that couldn’t or wouldn’t pay their

salaries. I have had hungry officers in the Ministry of Natural

resources or Agriculture, beg for a few Leones to help them feed their

families. The fishery offices in Freetown were formerly the British

Navy’s barracks in that port. In 1990 they looked as if they had not

been swept out, far less painted or repaired since the day the last

British sailor marched out. In some government offices there and

elsewhere in West Africa, files lay in a heap in the corner of the

offices of directors or senior administrators. Away from the capital,

government officers sat at empty desks beside typewriters that lay idle

due to lack of paper or ink ribbons. The roads in Freetown had potholes

every few yards, yet scores of diamond dealers were driving around in

Mercedes Benz cars while the vast majority of the people lived in

squalid circumstances.

Gambia, market scene

Cape Verde, former Portuguese base off

West AfricaI I visited these lovely but barren islands on behalf of

Iceland’s foreign aid programme.

Gambia, being a smaller

country, north of Sierra Leone, had less population pressure or urban

squalor. It also maintains a strong British culture inherited from

colonial days. One finds Africans who served with Scottish regiments,

still able to play the bagpipes with pride. Offshore, the islands of

Capo Verde, a former Portuguese trading ship base, are very different

from mainland Africa, but struggle to create a sustainable economy due

to poor soil, limited fresh water, and little tradable resource apart

from fish (mainly ocean swimming tunas).

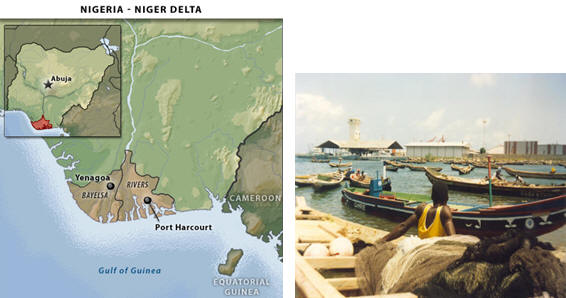

My experience with the

Shell Oil company of Nigeria gave me a glimpse of the problems created

when you have the extraction of enormous wealth from an area where local

people live in dire poverty. I had similar experiences with Caltex in

Indonesia. The Niger delta pays a heavy price in environmental damage

for the oil extraction business, and one can understand why this has led

to attacks on installations, and to bloodshed at times. To give Shell

its due, the company attempts to provide compensation, and in the Delta

area it operates an agriculture extension service bigger than anything

the federal or state governments could mount. My judgement was that the

reason this did not placate the locals was the manner in which the

service was provided. Shell’s pandered and well-paid local officers

(all black, - the whole company is locally staffed), strutted about like

little lords and treated the people accordingly. The locals were not

really consulted, - they were simply told what Shell would do for them,

and how they had to cooperate.

Similarly, my

recollections of Caltex in eastern Sumatra, are of a beautiful modern

floodlit complex behind a high barbed wire fence. Just outside the

fence, local fishers had to manhandle their baskets of fish up a steep

muddy path from the river below to a miserable shack set on top of a

rubbish dump, where their fish were auctioned. There were no facilities

worth the mention, - no clean water, toilets, or proper access for fish

vans or tricycles. And the fishers had to pay 10% of their sales income

for the privilege. Perhaps conditions have changed since, but the

contrast then was obscene.

Map of the Niger Delta where Shell Oil

has massive investments. West African marine canoes.

Oil, perhaps more than

any other resource, creates serious social tensions in poor countries

where the enormous income is grabbed by the ruling elite, with little

distribution down the economic ladder. Professor Michael Klare writes :

“When countries with few other sources of national wealth exploit

their petroleum reserves, the ruling elites typically monopolise the

distribution of oil revenues, enriching themselves and their cronies

while leaving the rest of the population mired in poverty – and the

well-equipped and often privileged security forces of these

“petro-states” can be counted on to support them. When the divide

between privileged and disadvantaged coincides with tribal or religious

differences, as it often does, violence isa likely outcome. The Western

press may describe such conflict as “ethnic” in character, but it comes

largely from the perversive effects of oil production.”

[The Dependency Dilemma, in Blood and

Oil, by M. Klare, Penguin, 2005]

With all its faults,

British rule in Africa never produced such horrendous results, - at

least, not since the Boer War which was a monumental foreign policy

disaster. Despite my obvious liberal and leftish views, I must admit

that colonial rule in the 20th century was largely beneficial

for the continent and its peoples. Some Governors were admirable men of

understanding and integrity. My wife and I bought a farmhouse in

Edinburgh from Sir Peter and Lady Isobel Faucus who had served in

Botswana after the war, and till the colony achieved independence. He

and his wife regularly entertained Africans studying in Edinburgh each

Christmas, in a former ‘bothy’ building behind our farmhouse, and we

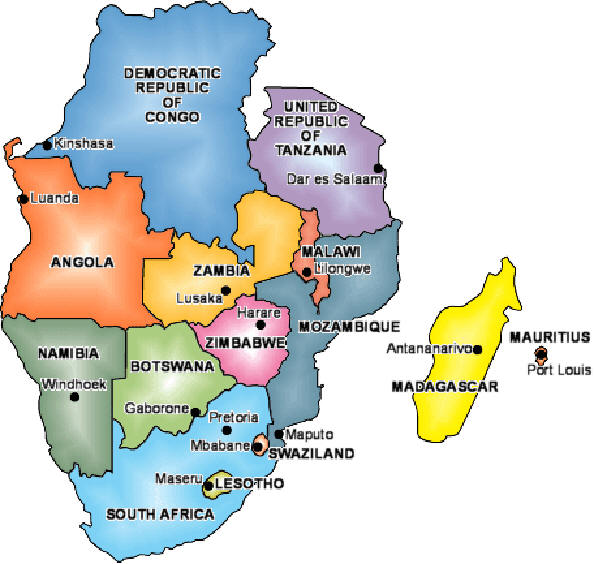

were also welcomed to these events. I had the chance to visit Botswana

when undertaking work for SADC, the Southern Africa Development

Community, in the 1990’s and found it peaceful and relatively prosperous

as Sir Peter had described it.

Are there not some

bright spots in Africa? Are there not at least a few success stories?

The answer is yes, and I will name two where I spent some time. One is

Ghana where the half-Scot leader, former flight Lt. Jerry Rawlings

managed to bring his country out of impending disaster to be the one

example in West Africa of reasonably fair and stable government and

profitable industry. The people are hard working and intelligent, and

while corruption exists, it is far from the extremes ones finds in most

of the continent. Rawlings called himself “Chairman” rather than

“President”. He avoided fanfare. I was driving around Accra in a taxi

one day when an ordinary-looking minibus passed us. The taxi driver

said, “Did you see who was sitting in the front of that minibus?

That was Chairman Rawlings. He doesn’t mind traveling about like an

ordinary citizen”.

Jerry Rawlings, former President of

Ghana. He had a Scottish mother.

Ghana was also the only

country where I met the Prime Minister [Not

quite correct. In Papua New Guinea I worked with Sir Mekere Maruata,

former head of the National Bank, who became Prime Minister four years

later, in 1999.]

Mr Oti gave me an hour of his time to explain how he wanted a fishery

sector investment project designed. I thought his ideas were sound and

reasonable, but when I took them back to the UNIDO office in Vienna,

they paid not the slightest heed to his suggestions and requests. Was

it any surprise the draft project was rejected ? But that was typical

of the ivory tower attitudes of some UN technocrats. Also, to my

surprise, my proposal to establish a tuna canning plant in Tema, was

ambushed by a team of French consultants in Vienna (they were against

any competition for the French canning plant in Cote D’Ivoire).

However, Ghana obtained alternative finance, and the canning plant went

ahead and is functioning to this day. That was not the only successful

fish canning plant whose establishment the UN tried to block. The other

was in Fiji, but that is a different story.

Another country in

Africa that gives me hope for the future is Namibia. Formerly

South-West Africa, a German colony before the war, and effectively part

of the South African state after the war, it achieved independence under

a SWAPO government in March 21 1990. Few gave it much chance of

survival as it had a population of only 1.5 million, and was mostly

desert, the Namib. But Namibia went from strength to strength. Its

mixed population of whites, coloureds and blacks, - both Bushmen and

Bantu, were surprisingly tolerant of each other, and the Government on

the whole behaved wisely. The fisheries sector was blessed with a

remarkable Minister, Helmut Angula, who spoke six languages, and had

written at least one book that I know of. He took over when the fish

stocks had been ravaged and depleted by South African and European

fleets. Angula set to work assisted by a brilliant fisheries economist

from New Zealand, Les Clark. He had the country claim its legitimate

200 mile EEZ and banned all foreign fishing. The local EU Commissioner

put every pressure he could on Angula to give European fleets carte

blanche to continue to rape Namiba’s fish stocks, but Helmut would not

budge. “I have hardly enough fish for our own fleet, - how can I

give some away to you?”, he told the commissioner. So despite all

sorts of pressure and threats to withhold aid, Namibia won. The EU

conceded, and today that small country has the most prosperous fishery

sector in all Africa. I reported the Namibia experience in a number of

papers and newspaper letters which led a senior Scottish civil servant

handling the fishery sector to remark, “We don’t want to hear another

word about Namibia, - we are fed up hearing that story” !

I was also able to

visit South Africa both before and after Mandela took over. What struck

me on my first visit was how many white South Africans were in favour of

the change, and were ready to do their bit to make it work. I also met

black ANC members of Parliament later, including one who regularly

visited Mandela in Robbin Island. They too were interesting characters,

though wary and suspicious of all whites, including liberal whites like

myself. But I found that also in the USA. The black American of the

1960’s did not trust the liberal northern white. He suspected, probably

correctly in many cases, that under the liberal skin lurked a latent

racist if the person was only put to the test in the appropriate

circumstances. My heart goes out to the new South Africa. It faces

immense problems. How do you provide housing, education, jobs,

health-care, clean water, and a future for 40 million disadvantaged

citizens. It is far from easy. But the country had the most marvelous

first post-apartheid President in Nelson Mandela, a man of tremendous

courage, character and determination.

Nelson Mandela

I enjoyed reading

Mandela’s biography, but was more moved by the account of his Robben

Island experience written by his former prison warder, James Gregory, “Goodbye

Bafana”. That is one of the finest books on Mandela, and on the

forces at work in South Africa. Previously I had read the series of

books on the country written by Michael Cassidy, an evangelical Anglican

minister, and many years before, Trevor Huddleston’s epic volume,

“Naught for your Comfort”.

Some tales from Cape

Province may shed light on the difficulties President Mandela faced when

attempting to redress years of racial injustice. Under the apartheid

government, black and coloured communities were largely excluded

from access to lucrative fish quotas and processing or marketing

privileges. This policy was quickly changed under Mandela, and the

fishing cooperatives of the black and coloured coastal towns finally

obtained reasonable access to fish stocks. But Mandela and his largely

black ANC government had to contend with a white bureaucracy that did

all in its power to nullify the changes. It was a case of ‘government

proposes, bureaucracy disposes’ ! When translating the quota

allocations into regulations, they added a number of restrictions that

prevented the communities from realizing the benefit of their newly won

quotas. For example, one community I visited had been granted a quota

for abalone, but were forbidden from selling them to any other merchant

or processor than the local white owned fish plant. With that monopoly

control on purchase, the white company could offer any price it liked.

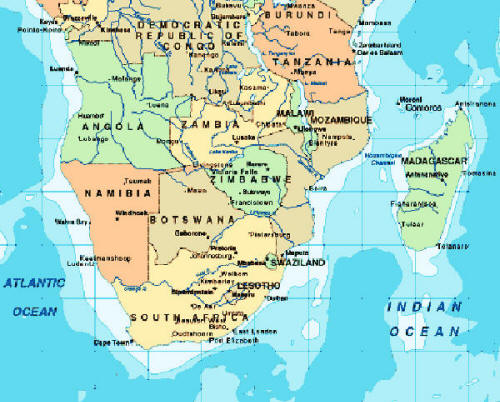

map of Southern Africa

Another coloured

fishing company got a quota for sardine or pilchard to catch which it

needed to buy a small purse seine vessel. I put them in touch with

sellers of a suitable vessel in Scotland, but when they attempted to buy

the boat, with a loan from a local bank, the bureaucracy refused them an

import license. Other indigenous fishermen operated a few long line

vessels for tuna. They had no income for the 4 or 5 months when the

migratory tuna left their shores. So they requested a small hake quota

for that season, which they would catch by using bottom set long lines.

This was refused on the grounds put forward by the white dominated

fishery research board, that unlike bottom trawling, “long lining

would be detrimental to the stock”. The argument that hook and line

fishing was damaging to the resource while the use of huge powerful

trawl nets was not, would have been laughed out of court in any of the

fishery countries of the north Atlantic!

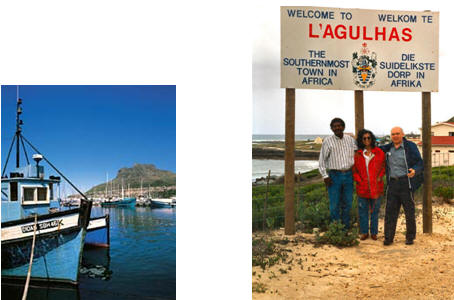

Cape fishing boats, South

Africa Johnny Issel, ANC MP, at the Cape of Good Hope

Together with a local

ANC member of parliament Johnny Issel, I visited a black and coloured

fishery cooperative in the Western Cape. They were hoping to expand

their operations from fish harvesting to processing and marketing, and

were seeking to form joint ventures with fishery enterprises in Britain

that might provide expertise and training, as well as assist them to

obtain the necessary equipment. We were well received and treated

generously. As we sat down to a magnificent meal of curried crab and

lobster, I asked Johnny if he said grace before food. He said no, and

passed the question on to the Coop Secretary. The man replied that he

was not a Christian and didn’t know how to pray. At that, one of the

members stood up, a black man called John Moses. He said he would say

grace, and then proceeded to give an eloquent prayer of thanks for the

food. He had bullet wounds in his legs from attacks by white fishers

who resented the coops newly allocated fishing rights and were disputing

the issue on technicalities. John told me that he was due in court soon

to answer their charges, and he fully expected to go to prison, not that

is seemed to bother him at all. That was how things were even after the

election of Nelson Mandela as President of the New South Africa.

An interesting

character who had an enormous influence on all of Africa through her

music, was Miriam Makeba. She was born in South Africa, and began her

career as a young woman. Now 73 years old, she has been singing for

Africa for over 50 years. Many a time in the bush station by lake

Kariba, we showed films to the staff and locals to provide some

entertainment on a Saturday night. Miriam Makeba’s singing performances

were always well received, and some young staff members like Aston

Musonda, my stores officer, were enchanted by the good looks and

beautiful voice of Makeba. Exiled by the Apartheid regime in her

homeland, she moved to West Africa for a period, where for a while she

was married to the American civil rights leader, Stokely Carmichael.

She returned to her homeland following the election of Nelson Mandela.

Makeba is still active today though she has ceased to give public

performances.

Above : Miriam Makeba, famous African singer. She was already widely

known and appreciated when I went to Africa in 1962, - and surprisingly

is still active in music and entertainment. She was once married to

Stokely Carmichael of the U.S. civil rights movement.

African music is

something special. They have a marvelous natural sense of rhythm which

is well recognized. Not so appreciated, but equally notable, are the

lyrics of popular songs written by African musicians. The songs have a

simplicity and a poetic appeal that I for one found fascinating. Few of

these simple African ballads find their way into the recording studios

of the USA or Britain, which I regard as pity. Some musicals and light

operas have been written by African musicians. One that sticks in my

mind is King Kong, a rather tragic tale about an African

heavyweight boxer who eventually ruins his life. If I recall some of

the lines from one song, they went : “King Kong, bigger than Cape

Town, King Kong, hundred feet tall, King Kong, no one can touch him, -

that’s me, I’m him, King Kong, King Kong. A man of stone, a man of

stone, King Kong, King Kong, he walks alone, he walks alone, King Kong,

King Kong.” That and many other pieces were acted out by an all

black cast swaying and singing in perfect rhythm and harmony.

The musical was written by Pat Williams and composed by Todd Matshikiza

around 1960, and was performed at least once in London.

Looking back on the

colonial era in Africa, the picture is mixed. There was reasonable

government in many if not all cases. Exploitation occurred to a degree,

but there were genuine benefits. Once the horrendous slave trade was

halted in the early nineteenth century, European interventions in the

dark continent were more concerned with trade and with strategic

military and political advantages. The Arab slave trade began earlier

and continued longer, but today it is Africans who sell Africans into

slavery, or abduct them to be child soldiers. My namesake, David

Thomson the historian, wrote in “Colonial Expansion and Rivalry”,

that in 1875, less than ten per cent of Africa had been turned into

European Colonies. By 1895, only one tenth of the huge continent had

not been appropriated. He also remarked that it was a historical

novelty that most of the world should then belong to a handful of great

European powers. I would not attempt to defend colonialism, but simply

note that since 1950, the last 25 to 30 years of Britain’s colonial era

was marked by decency and justice for the most part.

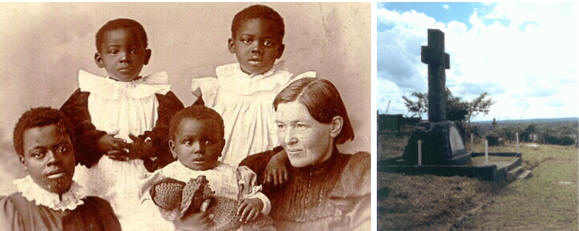

Mary Slessor of Dundee, the

indomitable missionary who saved the lives of countless numbers of

children and mothers in Calabar, Nigeria. On the right : her the grave

by the river, Calabar. Outside the local university there is a statue

of her above the roundabout with twin babies on her knees to recall how

she stopped the practice of infanticide.

The major colonizing

countries were France, Britain, Germany, Portugal, Belgium and Italy,

though Spain also held territory in West Africa. Dutch Boer farmers set

up the independent entities of Transvaal and the Orange Free State in

South Africa. The senseless Boer war was a result of British refusal to

recognize the Boer governments. Early clamour to grant independence to

colonial lands occurred in 1860 -1870, then grew rapidly after WW2.

Mostly the handover of power went smoothly except in a few sad cases

like the Congo, Algeria, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe; (interestingly, -

respective examples of Belgian, French, Portuguese and British rule).

Since obtaining

independece a disappointingly large number of black African governments

have displayed corruption and callous brutality beyond that of any

colonial regime, apart from South Africa where a white minority

maintained a brutal police state to suppress dissent and enforce

apartheid. Non-Arab or non-Muslim black Africans were also mistreated

by the regimes in power in the Sudan and some neighbouring states. It

did not help matters that during the era of decolonization, Africa was

caught up in the cold war power struggle between east and west, and in

the brutal attempts by the old South Africa, to destabilize black

governments and support mercenary-led insurgencies.

|

Brutality,

Interference and Manipulation

Petty tyrants,

supported by either the east or the west, emerged to inflict

appalling cruelty on their own people. Tribal loyalties and

differences were exploited by callous leaders to bolster their

grip on power. Mobutu in Zaire, the former and present Congo,

was typical of the worst of those supported by the west. While

his people remained at poverty level, he amassed over a billion

dollars. In Uganda, Idi Amin exhibited the worst traits of

brutal rule and ethnic cleansing. When he was eventually

ejected from the country, he was granted life-long safety and

comfort in Saudi Arabia. A different fate was reserved for

Moise Tshombe of the Katanga secession in the Congo. His

erstwhile European backers washed their hands of him and

acquiesced with USA and UN support for Mobutu. He was taken off

a flight headed back to Africa, but which was forced to land in

Algeria, where he was incarcerated and eventually died in

prison. No European government lifted a finger to help him

though his brief rule in Katanga was efficient and civilized. I

visited the Katanga during a trip to lake Mweru, and was

impressed by all I saw there. The local priest gave us

hospitality as did the nuns at a local hospital. Before we

left, the French and Bemba - speaking students of a fishery

school, all in bright sailor uniforms, linked arms and sung to

us “my bonnie lies over the ocean”. I often wondered

after what became of them. The UN troops under Connor Cruise

O’Brien were not far away.

The atrocities

in the Congo were to be out-done by more appalling massacres in

Rwanda and Burundi, and by the manipulated deaths by starvation

of hundreds of thousands in Ethiopia, and also in the Sudan and

Somalia. The wars in Angola and Mozambique were fomented by

western powers in cooperation with apartheid South

Africa. The dreadful Biafra war in south-eastern Nigeria was

over control of the oil wealth, and illustrated the sad effects

of colonial powers having carved out “countries” in Africa, with

almost no consideration given to ethnic or religious

differences. The ‘borders’ issue is not solely to blame for

Africa’s troubles, but it has been a significant factor in its

instability.

I visited Biafra

much later, on assignments for the Shell Oil Company and the

Petroleum Trust Fund, and spoke to several local persons who had

some memory of the conflict and the accompanying famine. But my

interest went back farther to the work of a Scots missionary

lady, Mary Slessor from Dundee, whose picture is on the current

Clydesdale Bank ten pound note. She built up a pioneering work

of schools and hospitals at Calabar, and is credited with ending

the tribal practice of killing at least one of any twin babies

that were born. There is a statue of her on a monument above

the roundabout outside the University there. Appropriately, she

is seated, with a set of twins, one on each knee.

|

Smoked fish in a West African

market. It takes a cubic metre of wood to smoke one tonne of fish.

There are half a million tones of fish smoked this way in West Africa.

This adds greatly to the demand for fuel wood.

map of Central Africa

|

Uganda’s sad

history

Among the lands

that suffered dreadfully from corrupt and despotic rulers,

Uganda stands out, having gone through a period of brutality and

slaughter from 1965 to 1985 under the alternate rule of two

despots. Milton Obote, (1924 – 2005) who led the country from

independence in 1962 till his overthrow in 1985, was surpassed

in his cruelty and mismanagement only by his own army chief, Idi

Amin, (1925 – 2003), who deposed Obote and controlled the

country from 1971 to 1979.

Obote was a

northerner, of the Langi tribe, part of the the Nilotic people.

Amin was from the southern kingdom of Buganda located around

Kampala. The two men set up a lucrative business smuggling gold

and ivory from neighbouring Congo. This was denounced by King

Frederick Mutasa II of Buganda. Obote dismissed his government

in 1966 and made himself president for life. On Obote’s

instructions, Amin destroyed King Freddie’s palace and murdered

200 of his staff and bodyguards. The two dictators grew

suspicious of each other, and when Obote tried to have Amin

arrested, his army chief took control and executed Obote’s

supporters.

Over the next

nine years, an estimated half a million Ugandans were to perish

under Amin’s brutal rule. He sent most of Uganda’s Asians into

exile, the people who ran most of the trading stores and service

companies in the country. This action crippled the economy.

Then in 1976 he gave refuge to Arab hijackers who had taken over

an Israeli flight. But the Israeli army and air force landed at

night and rescued the passengers, killing the hijackers in the

process. In 1978 Amin invaded the Kayera river territory of

Tanzania, prompting the Tanzanians to respond with a 45,000

strong army counter invasion which drove Amin out of the

country, first to Libya and later to Saudi Arabia where he

eventually died.

Amin’s expulsion

did not end the suffering of Ugandans. President Obote was

restored to power. He reactivated Amin’s horrid State Research

Bureau which continued to perpetrate atrocities for the next

five years. Another half million Ugandans were to die under

Obote’s second regime. He was eventually deposed by Acholi

soldiers (from a northern tribe that Obote had denied senior

military posts to award them to his own Langi tribe troops). In

June 1968, Obote fled into exile in Zambia. He died in South

Africa in 2005.

Today, Uganda

still suffers. To the north-east are the ‘Karamajong’,

cattle-rustling tribes people who can descend to murder of

villagers at times. To the east lies Democratic Congo, and over

there from the SE Ugandan border, there is a haven for a bunch

of warring rebel groups from Rwanda, the Congo, and Uganda, who

make forays into Uganda, but are repulsed by the UPDF the

Ugandan army. Chief among the internal rebel groups is the

‘Lord’s Resistance Army’ which is reckoned to be among the most

ruthless of armed bodies in Africa, that force children into

service in their mindless slaughter, robbery and abuse of poor

village people in areas the army can barely protect. Around

20,000 children are believed to have been abducted to date.

They now attack NGOs, even in southern Sudan, where they are

fiercely opposed by the Sudan People’s Liberation Army. Simon

Wunderli, a Swiss family friend, flies mercy missions into the

troubled areas every week. Speaking of the displaced persons

camps, and the rehabilitation centres for former child soldiers,

he says one abiding impression grieves him most :

“It’s

the void in their eyes, the lack of any glimmer of joy or hope,

the dullness of having seen things that nobody ought to see in a

life time.”

The current

President, Yoweri Museveni, continues to govern a one-party

state. Some fear that his regime is developing features sadly

similar to those of his predecessors’ misrule. |

Apart from the

brutality, corruption and mis-rule of many of its governments, Africa

faces a horrendous problem of destruction of its environment. This

relates in part to the survival mentality of the people, and the

practice of traditional ‘slash and burn’ agriculture that is practiced

all over the continent. In consequence, deforestation proceeds apace,

with soil erosion and desertification in its wake. The deserts are

expanding by leaps and bounds. Former water bodies like Lake Chad, are

now dried up holes. The need for firewood and for new fields to grow

maize or millet, keeps the bush destruction proceeding relentlessly. In

our development projects we placed great emphasis on fuel conservation

and use of alternative fuels and energy. We advocated planting and

operation of sustainable woodlots that could maintain families and

provide fuel and food, and prevent soil erosion. But these ideas were

rarely given the seriousness they merited from either African

governments or UN Agencies. I even advocated temporary import of cheap

wood fuel from South America to give time for African woodlots to be

established. But no, no one saw any merit in that, and so the

environmental destruction continued.

map of Southern Africa

One cannot help

comparing the attitudes and behaviour of Asian farmers with those in

Africa. Asia has its environmental problems too, but the beautiful and

complex tiers of rice fields and water channels one observes from Bali

to China and India, are the obvious results of generations of

painstaking investment in the future. Africans have rarely enjoyed the

luxury of long-term horizons. They are too concerned about where

tomorrow’s meal will come from. They may be dead next year, so why

conserve ? Their prime concern is survival, so they feel they cannot

afford the luxury of investing in a future they may not live to see.

And so they consume the seed corn of the future as they strip the

forests for fuel-wood, and fail to protect, replenish and enrich the

soil. I see little attempt to reverse this fatal direction, by either

national governments or aid organizations. Most of the staff members I

know in the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, have given up on

Africa. The oft-repeated description is that it is “a basket case”.

The only Asian country they say that of is Bangladesh.

Some states in Africa

are in a mess because of external interference as much as local

failure. I put Zimbabwe in that category. President Mugabe is brutally

ruining the country to grab land for his supporters and so hang on to

power. But he is able to do that and to gain a measure of support from

the blacks because the white settlers and the British Government have

together failed to address a problem that has been crying out for a

solution for over 50 years. Since the time of Cecil Rhodes, the land

has been viewed as ‘belonging’ to the colonials who took possession of

it and settled there in the benign climate. True, they developed

efficient tobacco and maize farms, livestock ranches and orchards, game

parks and safari resorts, - but it was all 90 % white owned. Had there

been a genuine effort since Ian Smith’s time, or even after Mugabe first

came to power, to equip and empower and train local farmers to take over

agricultural land in small stages, then perhaps much of the bloodshed

and violence might have been avoided. Perhaps.

My own impressions of

Southern Rhodesia as it was in the early 1960’s is that it had the

mildest, most placid population of Africans in the region, but also some

of the most ignorant and prejudiced “poor whites” I ever came across.

The problem of maintaining secure employment for the poor whites was one

that concerned the white governments in both Southern Rhodesia and South

Africa. Harold Wilson had first hand exposure to the mean, uncultured

bigotry of some of the whites in Rhodesia which he visited in October

1965 in an attempt to avert the state breaking away from the

Commonwealth. After dinner at Ian Smith’s residence, guests had to sit

through a rude, racist speech by a high-ranking expatriate, Lord Graham,

the Duke of Montrose, who related a stream of smutty stories, all

expressive of racial contempt for black people. Wilson later spoke of

those represented by Smith, Montrose and their cronies, as, “that

land-locked, introvert community”.

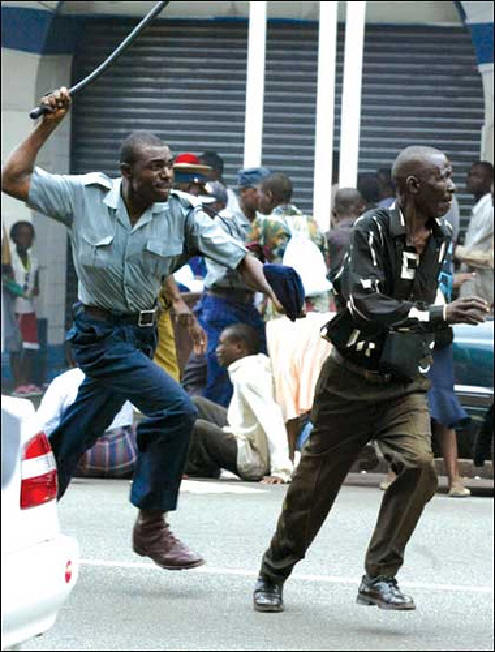

Zimbabwe police in action

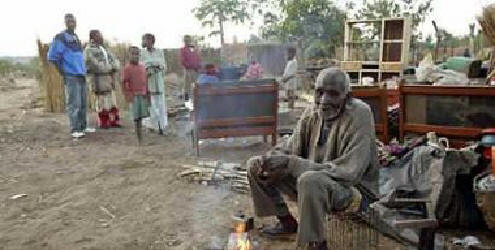

Harare dwellers evicted from

their homes take-over of a Zimbabwean farm

The sad lot of displaced persons

However, the present

collapse of Zimbabwe’s economy is due directly to Mugabe’s mismanagement

of the economy on a massive scale. He has killed the few industries

that were generating income and creating jobs, and has printed money in

large amounts to pay the army that keeps him in power, thus eroding the

value of the little savings his people had. The land reclamation

programme that could have been represented as a good form of wealth

distribution, has turned out to be a way of satisfying his cronies who

have shown zero skills in farm management, and a greater propensity to

exploit workers than was ever exhibited by the white farmers. Robert

Guest visited one of the confiscated farms. The new owner, a friend of

Mugabe’s wife, had evicted hundreds of black farm workers, and had their

houses ransacked to steal the severance payments that their previous

white employer was forced to give them before he was driven off.

Take Sierra Leone, that

has mineral resources and a productive land, a natural seaport, and a

strategic position for trade, - it could be the ‘South Africa’ of West

Africa. It was once self-sufficient in rice. Its diamond mines rival

those of South Africa, and its fisheries could rival those of Namibia

and Ghana. But it lies today, in abject poverty, with no government

worthy of the name, no security, and apparently, no future. Liberia is

in a similar mess. Yet those two states were to be shining examples of

freedom and progress as they were selected to be the homes of former

slaves returned to Africa. The Congo and Angola are other states that

have enormous oil wealth but are languishing in poverty, corruption,

lawlessness and insurrection. What went wrong, and can anything be

done?

Could a new form of colonialism give them stability and set

them on a course for prosperity. I once thought it might. But the

interference of western powers in other countries throughout the world,

the past thirty years, from Vietnam to Iraq, has been almost totally

disastrous. So I doubt if it would be any different in West Africa. It

would be wonderful if the global arms industry could be prevented from

selling any guns or ammunition to the continent of Africa, - it would

certainly help - but it would be a vain hope. As vain perhaps as the

hope that the rich countries would pay a decent price for the raw

produce and materials they import from Africa.

Below : about to board

a flight up the Mozambican coast, May 1993

a beach in beautiful Mozambique

I have thought long and

hard about the region’s debt, and whether it should just be written off

in a glorious international “year of jubilee”. But would Africa’s

corrupt rulers then use the new liquidity to buy medicines and school

books ? I doubt it. More likely it would be spent on luxury cars,

palatial mansions, and trips abroad, - if not also on weapons of

repression. So there needs to be corresponding mechanisms and

safeguards, along with the removal of debt, in order to ensure that the

new liquidity will not be abused. But that will be far from easy.

However, as discussed later, I believe that our national and global

financial systems are all biased in favour of the money lender and the

land owner. As in the gambling casino, or the game of Monopoly, the

banker always wins.

After considering

things at length, and examining all the evidence, it appears to me that

the best assistance Africa has enjoyed over the years, is not what came

from the World Bank or the EU, or from the U.N. as good as some of its

aid has been, but rather what has been provided in small amounts and in

simple projects by charities and missions and NGOs who were all working

on very modest budgets. Where would Africa be today if it had not had

the thousands of mission schools and hospitals ? – a lot worse off than

it is. When I was in Zambia, some communist sympathizers used to decry

the Christian charity. But I never in my life saw a hospital or a

school or a leper mission in a poor country that was financed or staffed

by Marxists or communists [That

is, outside of Cuba or Russia or China, and there the assistance

was government controlled.]. Never. They were mostly established and

operated by men and women who had given up all thought of financial

remuneration or the comforts of affluence, and had dedicated their lives

to ministering to the poor and disadvantaged, - all out of devotion to

Christ.

The terrible dark cloud

hanging over Africa today is that of the dread disease “Aids”.

In some countries like Lesotho, infection rates are nearly 40 %. Life

expectancy in the dark continent, which was never high, has dropped

considerably as a result. A really fine permanent secretary we had in

the Namibian Fisheries Department, died suddenly from the disease. It

made us realize that even healthy looking persons could be seriously

affected. Since drug companies stubbornly resist local manufacture of

their remedies that might be distributed at affordable cost, and since

it is hard enough for poor Africans to obtain or purchase even aspirin

or cloroquin, the chances of saving most of the aids victims are slender

at best.

Hope springs eternal in

the human heart, and it is so even in darkest Africa. There are

countries and peoples that could emerge from the chaos with dignity and

with the vision and drive to succeed. Given two big “ifs”, some

countries will make it. The first ‘if’ is that they get good

leadership. The second ‘if’ is that they are not subjected to outside

interference. Among those states with promise, I believe, are

Mozambique, Botswana, Namibia, Ghana, and tiny Gambia. And, we all hope

against hope, - the new South Africa. But who knows? The cards are

stacked against them, and they are surrounded by immense dangers within

and without.

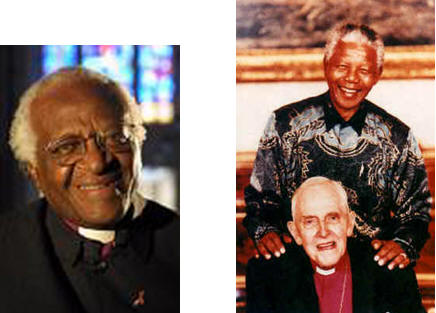

Yet, despite all the

injustice, cruelty, exploitation, and brutality, remarkable men and

women of conscience and moral leadership have emerged, and made great

contributions to the degree of progress achieved so far. South Africa

in particular produced three great men of such stature, - Nelson

Mandela, Desmond Tutu, and Trevor Huddleston. It is fervently hoped

that there will be more such leaders arising in the years to come.

Desmond Tutu, magnificent defender of

freedom and justice touched the

conscience of the world, with Nelson Mandela.

. On the right with President Mandela,

Trevor Huddleston, who laboured for years in South Africa, and whose

book Naught for your Comfort,

Perhaps I could do no better than close this chapter with

Trevor Huddleston’s prayer for the continent:

“God bless Africa. Guard her people. Guide her rulers.

Give her peace. |