|

I remember, I remember,

the house where I was born,

The little window where the sun came peeping in at morn;

He never came a wink to soon nor brought too long a day;

But oft since then I wished the night had borne my breath away.

I remember, I remember, the fir trees dark and high;

I used to think their slender tops were close against the sky:

It was a childish ignorance, but now ‘tis little jo

To know I’m further off from Heaven, than when I was a boy.

Thomas Hood (adapted)*

I was born in a village

on the Moray coast of Scotland, to fisher parents whose lineage had both

Pictish and Norse origins, - with possibly some Celtic and Lowland

mixtures. I was later blessed to marry an Edinburgh lassie whose people

were miners of Lowland Scots origins with some Continental traces. My

mother tongue was broad Scots of the Doric variety, - a language we were

not permitted to use at school or in any refined company. Local culture

in my childhood was marked to a degree by the “Scottish cringe”, and the

veneration of a national establishment that was very English in

character. The street where I was born carried such connotations in its

name, “Union Street”, as did the street of the second family home I

knew, “Dunbar Street”, named after Captain Brander Dunbar, the local

Laird. To further identify us with him, there was a Brander Street and

also streets called Victoria, King, Queen, and High, Street (after the

High church).

Sea breaking over the north pier Lossie. Typical conditions

following SE swell.

Right : East beach and mouth of the river Lossie.

Morayshire can claim a

unique and rich history stretching back to the period of the Roman and

Viking invasions. Julius Caesar is said to have sent his troops to the

mouth of the river Spey to investigate reports of pearls in the mussels

there. There were (and still are), pearls in those mussels, but they

are tiny and of no commercial value. (As boys we used to collect them

occasionally). Some 50 miles to the east, in Strathmore by Bennachie

just south of the modern A 92 road, the battle of Mons Graupius took

place, when Agricola defeated the Pictish king Calgacus. Burghead

harbour may have been used by the Romans as well as the Norse invaders,

but the date of its historic remnants is uncertain. Huge naval battles

may have taken place in the Moray Firth, between Norse fleets and early

Roman, Pictish or Celtic navies. But these battles took place in the

dim and distant past, and have few references in written history. The

early Christian church was established in Scotland in the 6th century

following the work of an Irish monk Colum Cille (Columba), who followed

men like St Ninian and St Mungo. It was at Loch Ness west of my home

where Columba first met the Pictish king, Brude Mac Maelchon whose

successor Gartnaich is believed to have embraced the Christian faith.

Under its original name

of Moravia, the district of Moray was an independent region of what

became the Kingdom of Scotland. It extended from the river Spey to the

east, to the Dornoch firth on the western side. For some centuries

Moravia resisted the imposition of both Norman Feudalism and Roman

Catholicism, (preferring the traditions of the Celtic Church to those of

the Roman pontiffs). Kings Alexander I & II, and King Malcolm, worked

to incorporate Moravia into the Scottish state, and into the Roman

branch of Catholicism, by appointing a Bishop in Moray in 1107, and by

establishing the Pluscarden Benedictine Priory in 1230. A later Bishop,

David de Moravia, was a leader of the northern independence movement,

for which he was excommunicated by Edward 1st. He went to Norway for

safety, but returned after Edward’s death.

King Macbeth of Scotland

1005 – 1057, was a Moray man, a grandson of Malcolm II, and Mormaer (or

governor) of that province, which was one of seven such districts in

medieval Scotland. He was a fairly competent ruler, by the standards of

the time, unlike Shakespeare’s cruel and tortured character. He is

believed to have resided mainly around Elgin and Burghead, both close to

my home of Lossiemouth, though Lossie town barely existed then, over one

thousand years ago. Being of royal blood, Macbeth was given a strong

Christian education by the monks of the time, as was the practice for

young men of his standing. His cousin Duncan 1 who was killed in a

battle with Macbeth, a few miles from my home town, was a rather

incompetent ruler. Macbeth in contrast displayed both ability and

justice in his administration. In 1050 he made a journey to Rome where

his generous almsgiving was recorded. Writers of his time describing

Macbeth used adjectives such as “renowned, generous, righteous, and

religious”. Some say that he was the last of the Celtic or Gaelic rulers

of Scotland.

Alexander Stewart, the lawless Earl of Buchan, better known

as the ‘Wolf of Badenoch’ a son of King Robert II and brother of King

Robert III, lived near Aviemore, from where he and his “wild, wicked

Heilandmen” made trouble for the authorities, and burnt down Elgin

Cathedral in 1390, after Bishop Bur had disciplined him and

excommunicated him from the Church. He is said to have sired 40

illegitimate children, and got rid of his legal wife to take in a

mistress. Following his misdeeds his father made him go through a public

act of repentance in Perth. However sincere it was, or not, he was

re-admitted to the church, and was later buried in Dunkeld Cathedral.

(In fact the real basis of Alexander Stewart’s quarrel with the Bishop

and other nobles, was over ownership and control of the Badenoch lands,

and of the lands held by his legal wife, Countess Euphemia of Ross who

had her marriage annulled by Papal Edict. The fury exhibited by the

‘Wolf’ at his excommunication, was due more to its impact on his earthly

prospects than his heavenly ones. As a Stewart and a son of the King,

it would have precluded him from ascending to throne of Scotland, had he

become next in line.) Below : A 19th century depiction of the

destruction of Elgin Cathedral by Alexander Stewart, “the Wolf of

Badenoch” in 1390 , and the ruins of the Cathedral, as they appear

today.

Scotland was ruled from Morayshire for a few brief periods since the

time of Randolph Stewart, Earl of Moray in the 14th century.

Traditionally the Earldom was responsible for government if and when the

monarch was in his childhood. The ‘Bonnie’ Earl of Moray, James

Stewart, a half brother of Mary queen of Scots, was Prince Regent of

Scotland during the infancy of James VI, and a leader of the Scottish

Reformation. He had his home at Forres, in Darnaway Castle, still in

fine condition. He was assassinated at 39 years of age in Linlithgow in

1570. One of our best friends has been taking care of the castle the

past 20 years for the present Lord Moray. Its coat of arms still bears

the motto given it by the Bonnie Earl, - saved through Christ’s

redemption. [The motto is in Latin : “Solus per

Christo Redemptori”.]

Moray, and the city of

Elgin, have seen a few invading armies over the years. The forces of

the English King Edward 1st were there in 1303. During the period 1651

– 58, Oliver Cromwell’s army, or part of it, was in Moray, and they are

credited with destroying much of what was left of the cathedral. In

1746, Charles Edward Stuart and the Jacobite army passed through Moray,

followed by the pursuing force under ‘butcher’ Cumberland, on their way

to Culloden Moor where took place the last land battle ever fought in

Britain. Culloden, the battle site, less than 30 miles from Moray, has

a ‘Stonehenge-like’ circle of standing stones, giving the area a link

with Druids of two to three millenniums ago. The battle of Culloden was

a watershed event for Scotland. John Prebble wrote, “Culloden … began a

sickness from which Scotland, and the Highlands in particular, never

recovered. This sickness and its economic

consequences emptied the Highlands of its people”. [From the author’s

foreword in “Culloden”, by John Prebble.]

The chief of those

consequences was the notorious ‘Highland Clearances’ of the first half

of the 19th century. Those who have read the history of that period,

will recognize the name of Patrick Sellars, factor to the Duke of

Sutherland, who was among the most callous and ruthless of those who

systematically evicted poor tenants from the estates to enrich himself

and make room for more profitable sheep. He came from Westerfield Farm

near Duffus, close to my present home at Covesea, and is buried in the

grounds of Elgin Cathedral. During his term as factor, he would

regularly sail across from the Beauly or Cromarty Firth, to Burghead,

from where he went by horse carriage to the market in Elgin to purchase

tools, equipment and supplies for the estate. The huge Sutherland

estate lies across the Firth from Morayshire, towards the north-west.

The infamous Duke was memorably described by Prebble. [From

“The Highland Clearances”, by John Prebble.] “He was coal and

wool joined by a stately hyphen, and ennobled by five coronets. The

glens emptied by his commissioners, law agents, and ground officers

(with the prompt assistance of police and soldiers when necessary), were

let or leased to Lowlanders who grazed 200,000 true mountain sheep upon

them, and sheared 415,000 lbs of wool every year.”

Map of old Moravia, the semi-independent part of medieval Scotland.

Note Spynie loch near the mouth of the river Lossie which was drained

later. Before 1600 it was open to the sea, allowing boats to land at

Duffus Castle and Spynie Palace.

More recently, Morayshire

has been the home of a new age community at Findhorn beside the Kinloss

air station. Gordonstoun school where several members of the Royal

family were educated, lies between Duffus and the RAF Lossiemouth

station. The Duke of Gordon whose home it had been, was reputed to

dabble in the occult, and to be involved in the smuggling trade. The

caves at Covesea nearby had tunnels that may have been used to secrete

contraband goods landed on the beach. They also have some inscribed

Pictish symbols dating back thousands of years. Some tinker families

lived in the caves during the 19th and early 20th centuries. A few were

still around when I was a young boy. They were generally accepted and

treated with a degree of compassion. One notable member of that small

tinker community in my parent’s time was a young woman with the

attractive name of Joyful. A more prosperous group of Romany people

were those who ran the shows and funfairs. Though they lived in

caravans, they were much more urban in their lifestyle than the gypsies

of southern England. A family we knew well, the Hewsons, ran an early

picture house in the town. Old Mrs Hewson was a character, but kindly

and generous. She had one son and seven daughters that I recall. The

family occasionally joined us for Christmas or New Year, and at least

two of them were buried from our house.

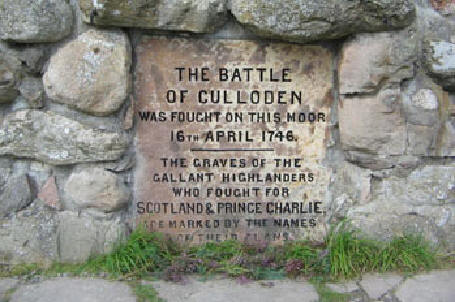

Culloden moor cairn and plaque recalling the last battle ever fought on

British soil.

It saw the end of the Jacobite cause, and the beginning of the

depopulation of the Highlands.

Farming thrived in the

valley of the Spey, Lossie and Findhorn rivers, producing barley,

potatoes, turnip, and other vegetables. Cattle and sheep grew well on

the local grass. Some reforestation took place in the last 50 years,

mainly of fir, silver birch and pine trees. Moray’s coast was the base

of a prosperous mechanised fishing fleet for over a hundred years till

that industry was destroyed by the European common fisheries policy.

There were fleets of small boats at Spey Bay, Seatown and Stotfield

(later merged into Lossiemouth), and at Hopeman, Burghead, and Nairn.

They have practically all gone, and have been replaced with a few yachts

in each harbour. Still flourishing however, throughout inland Moray,

are many whiskey distilleries.

Above : Gordonstoun School, near our home at Wester Covesea.

Several members of the Royal family were educated there.

Covesea lighthouse, built by the Stevenson family from whom came the

author,

Robert Louis Stevenson

My hometown has links

with the Stevenson family of engineers that built all of the lighthouses

in Scotland. Covesea light, (Covesea is an anglicized version of

“Caus’ie” or causeway) close to my present home, is one of the

magnificent creations of that remarkable family from which came Robert

Louis, the poet and writer. No doubt he visited the light designed by

his uncle Alan in 1846, as he did most of the family constructions,

during his youth. One of our later homes in Edinburgh was located close

to Swanston farm on the Pentland Hills where a sickly Robert spent some

of his childhood summers, and to the old Colinton Church Manse where one

of his uncles was Minister. And we were often in the New Town where he

was born. Then in my travels, as discussed farther on, I was to retrace

Stevenson’s voyages around the Pacific in the yacht Casco, and visit his

grave on Mount Vaea, in West Samoa. Another famous name who came

regularly to Covesea before moving to Canada, was Alexander Graham Bell,

whose family used to rent a cottage at Covesea village in the

summertime.

The benchmark I always

traced the family history from is my Grandmother’s birth; (my maternal

grandmother who lived with us). She was born in 1868, in the 31st year

of Queen Victoria’s reign, in the middle of the Disraeli and Gladstone

Ministries, and just 3 years after the assassination of Abraham

Lincoln. Karl Marx had just published Das Kapital, and Charles Darwin,

the Origin of the Species, 9 years earlier. That year Louisa Alcott

published Little Women, Charles Dickens was close to the end of his

active life, and Robert Louis Stevenson was a teenage student in

Edinburgh.

The

year she was born, a Lt Colonel in the U.S. 7th Cavalry, George A.

Custer, operating from Fort Riley in Kansas, was massacring Commanche

and Cheyenne Indians, men women and children, and burning their meagre

belongings. He and his troops also raped female Indian prisoners.

Granny was 8 years old when Custer and over 200 of his soldiers were

killed by a Sioux encampment he had attacked, and from whom he did not

expect much resistance, at the Little Big Horn river in Dakota. The

Indians were led by chiefs Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. Custer’s

campaigns were part of the military efforts to remove Indian people off

lands wanted by settlers and ranchers. Scant heed was paid to treaties

which the American Federal government broke time and time again.

Below : Sailboats and

steam drifters in the óld’harbour in Lossiemouth around 1910, the year

my father was born. The local fleet consisted of open boats powered by

oar and sailduring the 1800s. Steam drifters made their appearance

around 1890 and were at their peak at the outset of WW1. After the war,

the market for salt herring on the continent collapsed with the post-war

economies of Germany, Russiaand Poland. Lossie’s steam drifters were

sold or scrapped during the 1920’s.

Among the

children of the ‘Seatown’ where Granny lived, and with whom she attended

the two-roomed school at Drainie, just outside the village, was a boy,

two years her senior, by the name of James Ramsay MacDonald, the future

Prime Minister. He was later to build a house for his mother, Annie

Ramsay, in Moray Street, just a few yards up the road from granny’s

modest cottage. Ramsay named the house, “The

Hillocks”. It has its back to the street, and its front facing east

towards the Inchbroom wood and Spey Bay. I have been a welcome guest at

The Hillocks in recent times where JRM’s grand-daughter, kindly allowed

me to peruse his personal library and examine family memorabilia.

Ramsay’s study has been re-assembled with most of its original

furnishings and can be viewed in the Fishermen’s Heritage Museum at the

harbour. His grand-daughter Iona Kielhorn, has put the Hillocks living

room into the form it had when Ramsay visited Lossie, - exactly as it

appears in a photo-graph taken of the Prime Minister sitting by the

fireside, in the early 1930’s.

|

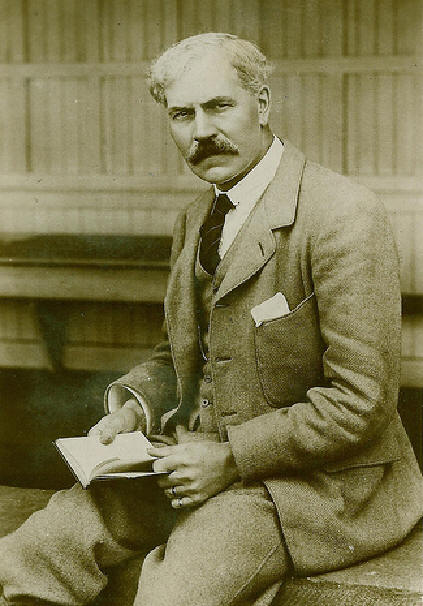

James Ramsay Macdonald

The first Labour Prime

Minister of Britain, James Ramsay Macdonald was born in my home

town of Lossiemouth on 1866, the only son of Annie Ramsay, a

servant girl who never married. He attended the local two-room

Drainie school just outside the village, near the present RAF

station. The teacher was a James MacDonald (no relation), who

was assisted by a sewing mistress and a pupil-teacher, to handle

the total of 70 pupils. Ramsay was kept on for a while as an

assistant teacher after he graduated. He later went to London

and Bristol where he found newspaper work, and married a

Margaret Gladstone from a middle-class family.

He joined the early Labour

Party, and was much admired by socialists and Fabians, including

Beatrice and Sidney Webb. He was elected a member of parliament

for Leicester in 1912, and joined Kier Hardie and other early

socialists at Westminster. He had pacifist views and opposed

Britain’s participation in the First World War. This stance

attracted a lot of criticism. Back home, he was ordered off the

golf course by the club secretary in 1915, and had his

membership terminated the following year. The secretary of the

Moray Golf Club, Jock Foster, Solicitor and Sheriff Clerk at

Elgin city, was by most reports, an arrogant man who later

became an alcoholic and eventually died in Bilbohall hospital

(the Elgin mental asylum) in 1946, nine years after the man he

scorned and kicked off the golf course had been buried with

national honours as a three time Prime Minister of Britain. (In

those pre-NHS days alcoholics were often cared for in mental

hospitals).

After the war Ramsay was

elected for Aberavon. In 1924 King George asked MacDonald, then

leader of the Labour Party, to form a government, which he did,

but it did not last the year, due to a scandal known as the

“Zionovev letter” which now appears to have been fabricated for

that very purpose. Gutter politics are not a modern invention!

Poor Ramsay often had his

illegitimacy and lack of wealth used against him. The English

newspaper John Bull, once printed a copy of his birth

certificate. Alexander Grant of Forres, owner of the McVitie &

Price biscuit company, provided Ramsay with table silver for 10

Downing Street, and a car for his use in Lossie. Grant later

received a knighthood, and even that sensible honour was a cause

for slander in the Tory press. Grant well deserved the title,

unlike the scores of Tory sycophants who were ennobled or

granted medals for little apparent service to the country. (Alex

Grant himself was a poor boy who was apprenticed to a bakery in

Forres which later developed into the large McVitie and Price

company. His breakthrough came when the manger asked to taste

some biscuits he was eating for lunch, which had been made by

his mother. The bakery boss said they were extremely good and

asked for the recipe. Young Alex declined to give it but offered

to help the business produce them. That was agreed and the home

bakes became the now well known ‘Digestive’ biscuits.)

Ramsay was Prime Minister

again 1929 – 1931, of the second Labour government, and from

1931 to 1935 of a coalition government formed to get all-party

support to fight the recession since his own party rejected his

over-cautious approach. Most Labour members saw this as

betrayal and the party has regarded him as a political traitor

since. They also felt that MacDonald became too friendly and

comfortable with the aristocracy, and enjoyed their apparent

adulation. There does seem to have been something of the rural

peasant’s respect for the genuine aristocrat in Ramsay, despite

his strong social beliefs.

His three administrations

failed to deal effectively with the economic crisis. His

Finance Minister, Philip Snowden clung with doctrinaire

tenaciousness to the gold standard and refused to devalue the

pound, which effectively ensured that the recession would

continue. Oswald Mosley, later the leader of the British

Fascist party, was a Labour MP and Minister then. He argued for

a Keynesian program to put the unemployed to work on nation-wide

re-forestation programmes. It could have been the basis of a

British “Tenessee Valley Authority” type economic intervention,

but no-one else in MacDonald’s cabinet had the vision to see its

potential. The plan was rejected and Mosley became a fascist.

Lacking an imaginative economic recovery programme Ramsay was

obliged to form a coalition government to tackle the recession.

James Ramsay MacDonald, three times Prime Minister of Britain

Some observers believe

that MacDonald was a spent force when he came to power.

Certainly he never got over the untimely death of his wife

Margaret Gladstone in 1911. He was a great believer in world

peace, and was a principal founder of the ill-fated League of

Nations. He foresaw the second world war due to France’s

intransigence over the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles,

and died in some disillusionment in 1937. He is buried in

Spynie churchyard by the ruined palace of that name, half-way

between Lossiemouth and Elgin.

Ramsay with his wife Margaret Gladstone, and mother, Annie

Ramsay,

and their first child that died later in infancy.

Ramsay’s son Malcolm was

later British High Commissioner in Canada, and served as

Governor in Borneo, Malaysia, Kenya and India. He was always

plain “Mr.” MacDonald, having refused offers of knighthoods and

elevation to the peerage. His sister Ishbel, once her father’s

housekeeper at 10 Downing Street, married a local chemist and

lived out her days in Lossie. She invited my father and mother

to meet Malcolm on one of his last visits to Lossie. The former

High Commissioner and Governor General sat on a little stool in

the corner of her living room, and chatted away happily with all

visitors from the eldest to the youngest. |

The city of Elgin was and

is, quite small as cities go, with a population of only ten to twenty

thousand persons. It was typical of the towns serving a surrounding

agricultural area. It has produced a number of persons of achievement,

including a notable writer Jessie Kesson, who came from an extremely

deprived background to produce novels of remarkable insight. Another

successful person was a chemist, George Thomson, (no relation), who made

an excellent (and very palatable) cod liver oil cream that was marketed

until the 1950’s. He won the Moray Open golf championship in 1913, and

was presented the trophy by Prime Minister Asquith’s daughter.

Lossiemouth was known for

other things than being the birthplace of a Prime Minister. But for

most of the British public, that was it. When first encountering Labour

Party scorn for our local hero, as a young lad, I had no idea why he

earned it. I recall a Strube [Strube was a Daily

Express cartoonist between the wars, - a Giles before his time, though

more political.] cartoon of the 1930’s with the cartoonist’s

little man passing seasonal compliments to various politicians.

“Christmas greetings”, he said to Ramsay MacDonald, “you’re the best

Prime Minister we’ve ever had, - from Lossiemouth”. The town was a

combination of three villages, - Seatown (or old Lossie), Branderburgh

with the harbour and town square, and Stotfield to the west. It came to

life in the 19th century with the construction of the lighthouse, the

installation of electricity, the extension of the railway line, and the

construction of the two harbour basins. The end of that century saw the

rise of the herring industry, and the rapid growth of a local fleet of

steam drifters. At one time there was a sign at the main railway

station in London, declaring “King’s Cross to Lossiemouth”. That was as

far north as the LNER line went. During the 1930’s the town had a major

air station constructed nearby. RAF Lossiemouth is presently the base

of Tornado squadrons and air-sea rescue helicopters. For some years

after the war it was a naval air station, under the name RNAS Fulmar.

Motor fishing boat Prestige, owned and operated by my paternal

grandfather and his sons. (circa 1925).

Unveiling of the WW1 War Memorial, 1923. My mother’s father is in the

foreground in the left hand corner. He was killed crossing the railway

line the following year. Below left : my mother and grandmother with

myself and my older brother as infants.

Granny

was a character, - very typical of working class Scots of her time. She

was firm, thrifty, hard working, honest to a fault, but also generous

and sympathetic. Like many Scots she did not hide her opinions, and

would not hesitate to contradict someone she disagreed with. She had a

store of old songs and ditties, and I wish I’d taken enough interest to

jot some of them down on paper. Long after her death I learned some odd

things about Granny from a local woman who ran errands for her. (My

mother would not have mentioned certain matters). One was that she

smoked a pipe, which was not uncommon in women of her class and time.

The other was that she enjoyed a wee dram. It had to be a wee one. She

never had money for luxuries. Her elderly line fisherman husband had

been killed in 1924 by the local train on his way to gather mussels for

bait. Granny

was a character, - very typical of working class Scots of her time. She

was firm, thrifty, hard working, honest to a fault, but also generous

and sympathetic. Like many Scots she did not hide her opinions, and

would not hesitate to contradict someone she disagreed with. She had a

store of old songs and ditties, and I wish I’d taken enough interest to

jot some of them down on paper. Long after her death I learned some odd

things about Granny from a local woman who ran errands for her. (My

mother would not have mentioned certain matters). One was that she

smoked a pipe, which was not uncommon in women of her class and time.

The other was that she enjoyed a wee dram. It had to be a wee one. She

never had money for luxuries. Her elderly line fisherman husband had

been killed in 1924 by the local train on his way to gather mussels for

bait.

She worked hard for

minimal wages to support her children till they were each through school

and earning wages. An earlier child she had in her youth, emigrated to

Canada where she went to work in the Yukon. Nell, a woman of sterling

pioneering character, married out there and raised a family in

Vancouver. Like many Scots emigrants she sent food parcels regularly to

her mother. Granny loved fish, and was the only person I recall making

“lichners”, small, semi-dried salted haddock which were roasted over hot

coals on the fire. They were the sweetest fish I ever tasted. I slept in

the same room as granny for a few years, and to this day can recall her

murmuring her evening prayers which to a wee boy, pretending to sleep,

seemed to continue for hours. My happiest memories of Granny are of

going round the garden to lift vegetables for the dinner. She would

often stop to make a whistle for me out of a leek, or once back inside,

make me a memorable bowl of brose, (a dish seldom seen in Scotland

now). She was adept at making jams, and her broth and tattie soups

were superb!

My mother had her hands

full looking after a fisherman husband and three sons, (our sister

arrived much later), with an unmarried brother and her mother all

staying with us in a bungalow that had just 2 small bedrooms and an

attic used by my bachelor uncle and my older brother. Before her

marriage she worked for Mr and Mrs David West who lived in a house

perched precariously on a shelf above the sea shore. David West was an

artist whose paintings are highly valued today. But like most artists

he struggled to make ends meet during his lifetime. Mother would take

me on the double-decker Bluebird bus to Elgin once a week to meet up

with and buy some eggs from a cousin of her mothers from Fogwatt village

in the country where she kept a few hens. While in Elgin, the main

treat would be a sweet out of Woolworths. Sweets were rationed and

required a contribution of ration book coupons which were used with

care. When my father fished in the Republic of Ireland, which did not

have any rationing restrictions, he would return with a suitcase full of

sweets that were liberally distributed among my friends. Nylon

stockings and other feminine luxuries were brought back for mother and

her friends.

Mother’s brother, my

bachelor uncle, was a gardener then. A voracious reader of non-fiction

(I believe he had a prejudice against novels), he maintained a sizeable

library of Penguin and Pelican paperbacks, biographies, and accounts of

famous trials. There was an old wind-up gramophone

in the attic cupboard by his bedroom. We would search among the rusty

needles to find one that would not scratch so much, and then listen to

His Master’s Voice recordings of Paul Robson, John McCormack, Robert

Wilson and other singers of that period. As a boy my uncle had had a

newspaper round, and used to recount which papers he would deliver to

the different members of Ramsay MacDonald’s cabinet and shadow cabinet,

when they came to Lossiemouth for meetings in the Stotfield or Marine

Hotel there, when Parliament was in recess. According to one of his

grand-daughters, Ramsay once brought Ghandi to Lossie, but no-one

remembers setting eyes on him. Perhaps our weather kept the Mahatma

indoors.

Recollections of my

father are dim for early childhood, probably because he spent long

periods away at sea. When at home he loved to take us across the golf

course on a Sunday (there was no Sunday golf then), and show us bird’s

nests which he was adept at locating. The wooden lifeboat that fishing

vessels carried then was often left ashore to make room for fishing

gear. Dad would row us out on his one, to the offshore rocks of the

Skerries in the summer, and would whistle to attract the seals

alongside.

Lossie harbour from the air

Lossie town from the sea

Apart from the three

uncles on my mother’s side, there were seven uncles and two aunts on my

father’s side, - plus their spouses. The family enjoyed great

camaraderie and would rally around each other at times of crisis or

bereavement. It was a treat on occasional Sunday evenings to gather

with them at my paternal grandmother’s house, and hear them share their

news and views. As a young boy I regarded their collective wisdom with

some awe and admiration. The wives would meet once a week at each

other’s homes for an afternoon tea and gossip. All the while they

talked, their knitting needles clicked away speedily as they made

jerseys, pullovers, cardigans and kiddies clothes with great skill.

Their cable stitch jersey patterns were particularly admired by visitors

from the south.

My Father was never a

reader, but he was a great conversationalist, and as such was welcome in

any company. I have never met his equal at striking up conversations

with complete strangers in a railway carriage, and keeping them

entertained, to their obvious pleasure, the whole journey. He was one

of the finest tellers of jokes, and could make almost any tale sound

humorous. Children everywhere loved uncle Jimmy as they called him. He

had an enormous store of practical jokes and conjuring tricks that never

ceased to fascinate them. Dad was also the most non-judgemental person

I have ever met. He looked on none with prejudice, and could befriend

almost any type of person. Despite his noncomformist background, he

warmly embraced believers from all denominations. He was as happy in

the company of Catholic nuns as he was with Salvation Army girls. There

were only two human traits I recall that angered him. One was meanness,

and the other was religious hypocrisy. Most human weaknesses he regarded

with compassion. Once when fishing in Ireland, he had mentioned to the

local Gardai police in Galway that fish baskets were regularly

disappearing from the deck when the boat was in port. He was annoyed

later when he was asked to appear in court as the authorities had

recovered the baskets and arrested a culprit. The man who was found

guilty was unemployed and had a large family. He was given a severe

lecture by the magistrate and fined for his misdeed. My father went to

the court clerk afterwards and paid the fine for the man. That was

typical of him.

Boats landing their catches at the fish market My

father’s first boat, the Amaranth, 1934

He was a conscientious

objector during the war, but volunteered for the medical corps and for

non-combatant service in the merchant navy. The tribunal, however,

treated him with surprising respect and decided he should continue to

fish to help maintain that part of the country’s food supply. Such

concessions were regarded with some odium in the community since it

permitted the ‘CO’s to earn good money, but my father never mentioned

the criticism he must have received, though mother once alluded to white

feathers stuck to their front door. Other uncles served mostly on MFV

tender boats in Scapa Flow. One maternal uncle joined the army and was

among those rescued at Dunkirk. One of my father’s brothers served in

the latter part of the First World War, but it was from my wife’s family

that I have more stories of that conflict.

|

World War 1 Memories

My wife’s family had some

interesting wartime experiences. Her grandfather’s brother who

often stayed with them after he was widowed, was a sapper during

the first world war. He spent some months at the front near

Ypres and witnessed much of the carnage in the dreadful trenches

and occasional hand-to-hand combat in no-man’s land. Coming

from a mining community, he knew of the underground tunneling

the army organized to place explosives underneath the German

trenches. He often told of a time when a German pillbox armed

with machine guns was cutting down attacking troops.

Eventually, with the support of tanks, the British ‘Tommies’ got

close enough to lob grenades into the pillbox which then fell

silent. Andrew was one of the first to enter the damaged gun

position. As was the custom with troops of the time, he took

some souvenir items from the bodies of the German troops, which

he brought home with him after the war ended.

Years later, back at home

in Scotland, Andrew was examining the items which included

letters and a Bible inscribed to the young soldier Karl Fritz

from his mother. He thought, “maybe this man’s family would

like to have these things”, and so he wrote to the family

through the German consulate. You can imagine his surprise a

few months later to learn that the soldier’s family in Bavaria

were indeed pleased to receive the materials, but also that

Fritz himself, was still alive. He had only been blinded and

knocked unconscious by the blast. An Edinburgh doctor helped

restore his eyesight at a prisoner of war hospital, and he was

repatriated after the war. The family invited Andrew to visit

them in Germany. For domestic reasons he was unable to go, but

sent his son instead. The story gets more intriguing in that

Fritz’ son was captured during the second world war in the same

locality where his father was nearly killed. Information

reached Andrew who sent food parcels to Fritz junior, to the

prison camp in France, something the authorities sternly

disapproved of. After the second war, both families were to

meet again in Scotland and in Germany.

Another story from the

first world war illustrates the insanity of our governments

training and sending young men out to kill, who in ordinary

circumstances would have no ill feelings towards each other at

all. A fish merchant friend of my father’s Johnny West, who had

a share in the family boat, was a soldier in the first world

war. Sometimes, particularly if he had taken a drink (not that

he was a drinker), a memory would come flooding back that he

would have to share, - rather like Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner.

It concerned his first contact with German troops at the front

in France. He had charged with his company out of the trench

and across no-man’s land where they met the oncoming enemy. A

German soldier lunged at him with his bayonet, but John

sidestepped, deflected the blow as he had been taught in

training, and brought his own bayonet up into the man’s chest.

The young soldier collapsed, mortally wounded. Johnny knelt

down beside him and the man motioned to him to take a wallet

from his pocket. Inside were letters and pictures from his

family. The German indicated he would like Johnny to write to

them and tell them what happened. This Johnny assured him he

would do, and with that the young soldier died. Johnny used to

say that once that incident was past, he could have killed the

whole German army and it would not have bothered him; but that

first action of taking the life of another human being stuck in

his throat, and remained etched on his conscience for the rest

of his life.

Similar deep traumas faced

our troops during the 2nd world war. A D-Day veteran Frank

Rosier, recounted on BBC television how he shot and killed a

young blonde German soldier at close range in France in 1944.

Frank sat down beside the shattered remains of his enemy and

wept like a child.

The Conservative Member of

Parliament from Buckie, Sir William Duthie, who was later to

show me around the House of Commons, and who kindly wrote the

foreword to my first book, told me of his WW1 experiences. He

was wounded at Passchendaele, and lay

bleeding from wounds in the mud of no-man’s land for two days.

Eventually he was found and taken to a hospital where he

gradually recovered. The experience affected his attitude to

life from then on. While he was convalescing, he received a

letter from an older acquaintance, a schoolteacher who he had

thought before never held a high opinion of him. The writer

said that he believed Bill had the character and ability to

accomplish anything he set his mind to in life. Young Duthie

took that to heart and went on to a career in banking in Canada,

then in food supply organization in Britain during the second

war, then as a Member of Parliament for his home county of

Banffshire, and latterly as one of the finest honorary Chairmen

of the R. N. Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen. |

My grandparents’

generation lived through the period when the ‘workhouse’ was an ever

present danger to those who fell into destitution. The fear of that

dreadful place must have led to the virtues of thrift, hard work and

independence that characterized the sturdy sterling peasant people of

that time. The little city of Elgin produced such a character.

She was

actually born in Inverness, and brought up in Elgin, before being moved

to an orphanage in Skene. But Morayshire was the land she always

claimed as home. Jessie Grant MacDonald was born in a workhouse in

1916, and like the Dickensian waifs she resembled, she was

illegitimate. Her poor mother was a rich store of songs and poetry but

Jessie was taken from her by the authorities in Elgin while still a

juvenile. After orphanage and some farm service, she married a Johnnie

Kesson, a skilled farmhand. They moved to the Black Isle where the

couple had two children. Jessie possessed a remarkable skill in

writing, particularly in the Doric tongue. Her abilities were noticed

by Nan Shepherd and Neil Gunn, and she was soon writing for the Scots

Magazine, and for BBC Aberdeen radio. She was

actually born in Inverness, and brought up in Elgin, before being moved

to an orphanage in Skene. But Morayshire was the land she always

claimed as home. Jessie Grant MacDonald was born in a workhouse in

1916, and like the Dickensian waifs she resembled, she was

illegitimate. Her poor mother was a rich store of songs and poetry but

Jessie was taken from her by the authorities in Elgin while still a

juvenile. After orphanage and some farm service, she married a Johnnie

Kesson, a skilled farmhand. They moved to the Black Isle where the

couple had two children. Jessie possessed a remarkable skill in

writing, particularly in the Doric tongue. Her abilities were noticed

by Nan Shepherd and Neil Gunn, and she was soon writing for the Scots

Magazine, and for BBC Aberdeen radio.

In 1958 she published her

first book, The White Bird Passes. It is a moving account of her early

childhood, and the deprivations and hardships she had to endure. This

was followed by Glitter of Mica in 1963, and Another Time, Another

Place, in 1983. By this time she was writing scores of plays for radio,

and even produced BBC’s Woman’s Hour, for a period. In 1980 the

Universities of Aberdeen and Dundee awarded Jessie honorary degrees, - a

wonderful tribute to the illegitimate workhouse child brought up in the

back streets of Elgin. Jessie Kesson died in London in 1994.

An interesting aside to

her origins (which might have made great material for a Dickens novel),

concerns the identity of her father. Local reports in the town library

records indicate that it was believed he was the Sheriff Clerk and local

Solicitor, Jock Foster, though he never owned her publicly or made any

contribution to her upkeep or education. Foster’s main claim to fame

was the removal of Ramsay MacDonald from membership of the Moray Golf

Club for his anti-war pacifist views. Interestingly, Jessie’s

conception and birth occurred during the year of those events. One

could scarcely conceive of more different lives, and more different

characters than Jessie Kesson and her reputed parent, the arrogant Jock

Foster. If the story is correct, then at precisely the time when he was

having Member of Parliament J. R. MacDonald removed from the Golf Club,

he was using, or indulging in an illicit affair with, a poor Liza

Macdonald in Elgin where he was a prominent citizen, and she lived in

the local workhouse from where she was at times procured by male

clients.

The first five years of

my life were the years of World War 2. I was born just after British

troops evacuated from Dunkirk, and Hitler’s forces took over Paris. One

of my mother’s brothers, Uncle Joe Baikie, was involved in the Dunkirk

evacuation. I recall him relating to me his account of that event when

I was still in primary school. That was the year of the Battle of

Britain that turned the tide of war and prevented a German invasion from

taking place. The young Spitfire and Hurricane pilots who held the

Luftwaffe at bay, rightly earned the respect and admiration of the whole

nation. As Churchill put it so well, “Never in the history of human

conflict, was so much owed by so many to so few”. But other armed

forces branches suffered severe losses, including the Army, Navy, and

merchant navy. Our little community lost local men in each of these

services.

My memories of the war

years are of service personnel in uniform, nissen huts, tanks traversing

our streets and breaking up the tarmac in places as they did so. I also

recall well the ration books with their precious coupons. Shops lacking

fresh foods, sold powdered eggs, and powdered milk. I think it was

after the war that the Attlee government provided vast quantities of

concentrated orange juice as a health food supplement for children.

Strangely, after a few years the orange juice lost its attraction, and

the public started to buy more expensive commercial juice which was

probably of a similar quality. Overall I do not recall any deprivation

or hardship in the war years. [Interestingly, an East

German friend of mine, now deceased, who fought in the war, and was

brought up during the 1920’s and ‘30’s, told me that he had no childhood

recollection of hardship in Germany though it certainly existed.]

We were more fortunate than city people, having regular access to fish,

and to produce from local farms or gardens. However, like most families

our diet was modest. Chicken was something we saw once a year, at

Christmas. It is strange recalling that now when it is a common and

low-cost meal. Food parcels from my mother’s half sister in Vancouver,

Canada, were a special treat during and after the war. I well remember

the Betty Crocker’s cake mixes. [Apparently there

never was a ‘Betty Crocker’. The name was concocted by the Mills food

corporation to add a personal touch to their flour and baking products.]

Scapa Flow where many fishers served during WW2

A Nissen hut from WW2 days

A Lancaster bomber of the RAF. Such planes from RAF Lossiemouth sank the

German battleship Tirpitz in the Norwegian Tromso fjord on 12 November

1944. The 617 squadron was led by CO JB Willy Tait, and was formerly

commanded by Guy Gibson and Leonard Cheshire.

Servicemen and service

women were often in our house. In wartime days, most doors were open to

them, and some lifelong friendships were formed then. I remember the

service women who visited my mother – the “WAAFs” as we called them. My

bachelor uncle told of a slightly amusing incident when a Polish soldier

who had practically no English, came into a house one evening where he

was sitting in the kitchen chatting with the housemaid. There was

little else to do in a wartime village evening, but visit. The Pole sat

with them for a while but as he could make little conversation, became

somewhat uncomfortable. Pulling a Polish-English dictionary from his

pocket, he found a word to which he drew my uncle’s attention. Looking

at the maid and my uncle, he pointed to himself as he indicated the word

with a question on his face. The word was “obstacle?” !

There were Nissan huts

and pill boxes all around town, and our beach still contains the huge

concrete blocks that were erected in rows to hinder invasion. Barbed

wire was a constant danger to young boys and we often tore clothes or

cut our feet when playing around it. Today all trace of the barbed

wire, Nissan huts and bomb shelters is gone. Only the beach guarding

concrete blocks and some pill boxes remain.

Our garden contained a

concrete air raid shelter, a rather flimsy construction as I recall, and

we had both gas masks and tin helmets in the house. A regular broadcast

we listened to was from the “British Forces Network in Germany” with

Wilfred Pickles as compere, and the theme

tune, “Have a go Joe, come and have a go”. By then I guess the war had

ended, though apart from a faint memory of flags on Victory Day, I

scarcely recall its passing, or the explosion of the first atom bomb,

three days after my 5th birthday, or the horrendous destruction of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki the following month.

My father and crew of the MFV Resplendent repairing gear at their net

shed

which is now a fine restaurant.

The Resplendent INS 199 in Aberdeen, 1946, after rescuing the crew of

the Newark Castle when that trawler sank in the North Sea. Over ten

years later we met the skipper of the Newark Castle in Scrabster. He

asked my father if the company that owned it ever thanked him for the

rescue. My Dad told him that they had not, but that they just sent a

lorry to collect a trawl net and deck gear the crew had retrieved before

the boat sank. The skipper’s comment then was unprintable

! (Ressplendent was my father’s second command). |