|

The

largest and noblest surviving member of the ancient British fauna, the Red

Deer to-day has a very limited range—the mountain glens of Scotland and

Westmorland, in the north, and the wide Devon and Somerset moors and the

New Forest in Hampshire. Even in the New Forest, where only a few score

remain, it is extinct officially, for an Act of Parliament passed in the

year 1851 decreed the extermination of the Deer, the reason being that

they destroyed a vast quantity of what had then become of far greater

national value than venison—the growing timber, and demoralised the

inhabitants by creating a race of deer stealers. The

largest and noblest surviving member of the ancient British fauna, the Red

Deer to-day has a very limited range—the mountain glens of Scotland and

Westmorland, in the north, and the wide Devon and Somerset moors and the

New Forest in Hampshire. Even in the New Forest, where only a few score

remain, it is extinct officially, for an Act of Parliament passed in the

year 1851 decreed the extermination of the Deer, the reason being that

they destroyed a vast quantity of what had then become of far greater

national value than venison—the growing timber, and demoralised the

inhabitants by creating a race of deer stealers.

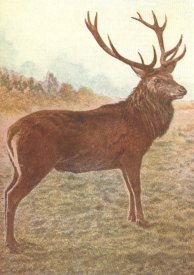

A full-grown Stag, as the

male Red Deer is called, stands about four feet in height at the shoulders

; the Hind, or female, somewhat less. The summer coat is reddish-brown,

sometimes golden-red, which changes to a brownish-grey in winter by the

new growth of grey hairs. On the under parts the colour is white, and a

patch of white around the short tail furnishes a " recognition

mark," common to most of the Deer family, which serves to guide the

herd when they are in flight before an enemy.

If one were seeking to

judge the habits of the Red Deer, one would feel justified in saying, as

many have said—" This is a creature of the open mountain-side and

the moorland, where there are no trees which could entangle those

branching horns." Yet the Deer can actually run through dense woods

with ease, and we know from its habitats in other countries where it is

still plentiful, that it is a true woodland animal.

When pursued and he takes

to the woods, the Stag throws his head back so that his antlers lie along

each side and protect his body from many a bruise that might otherwise be

inflicted by the branches as he rushes through the undergrowth. The

antlers may be used with deadly effect in self-defence, and many a hound

is killed by a Stag at bay. Their function appears to be mainly protective

against carnivorous beasts ; they are seldom if ever effective against

those of their own kind.

In spring and summer whilst

his horns are growing the Stag lives apart from his kind, but in the early

autumn when these are well-developed and hard, we may in suitable

localities hear his "belling" call to the Hinds, or in defiance

to some rival.

There is a good deal of

furious fighting when two jealous Stags of similar age and strength meet

in the vicinity of the hinds. He is then in the prime of condition, his

neck and shoulders clad in a thick mantle of long brown hair, and his head

adorned with the noble pair of antlers that reveals his age. Those that

decorated and armed him last autumn and winter were shed bodily about

March, and a new growth started soon after from the burred frontal knobs

that were left.

The mating of the Red Deer

takes place in the autumn; and in the spring the Hinds separate, each

retiring to a lonely spot among the bracken where her single calf (rarely

two) is born about the end of May. The little deer is already covered with

fur, and its back and sides are dappled with white after the manner of the

Fallow Deer, though unlike the livery of that species the spotting of the

Red Deer is not retained beyond calfhood. A hind bears her first calf when

she is about three years old.

The food of the Deer is

herbage and the young shoots of trees and shrubs. It is this fact that led

to their nominal extermination in the New Forest and other places. By

nature they are woodland animals—although their greater prevalence

to-day in the Highlands might give us a different impression—and in the

winter especially do great damage to the plantations of young trees.

Agricultural lands in their vicinity also suffer greatly, a whole field of

turnips being mined in a night by a visit from a herd of Deer. They also

destroy wheat, potatoes, and cabbages ; and in the woods consume many

toadstools, acorns, and chestnuts.

It is in the northern

localities quoted above that there is still the best chance of studying

the Red Deer under natural conditions. But the southerner has also a

prospect of meeting with the noble beast on Exmoor and in Hampshire, to

say nothing of the tamer herds in parks. To get a good view of these, they

should be approached with a pretence of unconcern they can often be well

observed from a road at a few yards’ distance without arousing their

suspicions, whereas a few steps towards them on the greensward will cause

them to bolt.

It should be stated that

the British examples of the Red Deer are considered to constitute a

geographical race known as scoticus. The European range of the

species extends from the Mediterranean to central Sweden and centraI

Norway. |