|

THE wild-cat is now rare in this country. Although I have

spent a great part of my life in the most mountainous districts of Scotland,

where killing vermin formed the gamekeeper's principal business, and often

my own recreation, I have never seen more than five or six genuine

wild-cats. Many, on reading this, will perhaps wonder at my statement, and

even give it a flat contradiction, by alleging the numbers that have come

under their own notice. Nay, I was even gravely told by a gentleman from the

south of England, a keen observer and fond of natural history, that there

were wild-cats there, [I have been frequently assured that wild-cats have

been killed on the Cumberland and Westmoreland hills; but, never having seen

any specimens, I cannot speak from my own knowledge. There is no doubt that

martins exist in some of the most hilly and wooded districts of England.]

and the skin of a cat killed in one of the southern counties was sent to me

as a proof ; this, I need hardly say, was the large and sleek coat of an

overgrown Tom, whose ancestors, no doubt, had purred upon the hearth-rug.

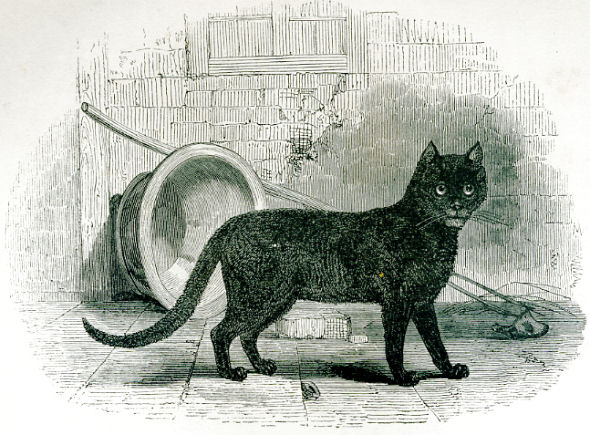

I am far from meaning that

there are no cats running wild in

England; of course, wherever there are tame cats, some of them, especially

the very old ones, will forsake their homes, and live by plunder in the

woods. These may also breed ; but their progeny, though undomesticated, will

always be widely different in habits, in appearance, in strength, and in

ferocity, from the true cat of the mountains. I have seen no less than

thirty of these naturalized [The

mischief done to game even by the house-cat, especially if halfstarved in

the cottages of the poor, may be shown from the admission of a witness whose

evidence will not be doubted. A friend of mine had shot a large cat in a

covert adjoining the cottage of an old woman, and, being rather pleased at

ridding the preserve of such an enemy, was carrying it too ostentatiously

past her door. She rushed out in a fury, demanding "how he dared to

kill the best cat in a' the country?" He replied, that "wandering cats were

never of much use for mice." "Mice! Wha's speakin o' mice, or rats

aither ? There was scarcely a day she did na bring in a young hare or a

rabbit or a patrick. Use ! It wad

be somethin' to be proud o', if they ill-faured brutes o' dogs o' yours were

half as usefu' !!"] wild-cats trapped in a year in a single preserve

in the Highlands; some of them might have been mistaken for the

genuine breed. The colour in both was pretty much alike, but there were

other points which clearly showed their domestic origin. They were, in fact,

a cross between the wild and tame cat. I have seen many of this kind stuffed

in museums and collections, as fine specimens of the wild-cat, and believed

to be so even by those who might have known better.

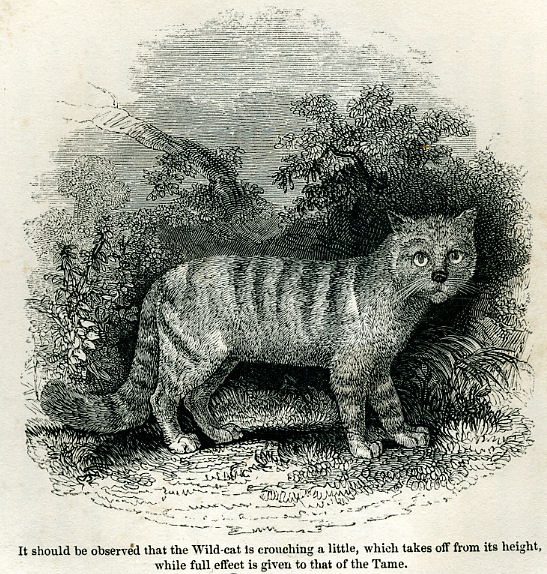

The unerring marks of the

thorough-bred species are, first, the great size, - next, the colour, which

does pot vary as in the domestic animal, but is always a dusky gray,

brindled on the belly and flanks with

dingy brown hair long and rough, - the head exceedingly broad, - ears short,

tusks extremely large. Another very distinguishing point is the great length

and power of the limbs. It stands as high as a good-sized dog. But perhaps

the most unfailing mark of all is the tail, which is so long and bushy as to

strike the most careless observer. In the males it is generally much shorter

than in the females, but even more remarkable, being almost as thick as a

fox's brush.

The woodcut is taken from the largest

female that has ever been killed in Dumbartonshire, and most correctly shows

the difference of its size from that of a full-grown house-cat. It was

trapped on the banks of Loch Lomond in the depth of winter, having come down

to the low ground in quest of prey. The bait was half a hare, hung on a

tree, the trap being set immediately under. The person who went to inspect

it thought, when at a little distance, that a yearling lamb was caught. As

he came near, the cat sprang up two or three feet from the ground, carrying

the large heavy trap as if scarcely feeling its weight. He would have had

great difficulty in killing it, had he not dodged round the tree when aiming

a blow. I have seen two males bearing the same proportion to this specimen,

both in size and fierceness of aspect, as an old half-wild Tom to a

chimney-nook mother Tabby. One of these was shot by a gamekeeper, when on a

grouse-shooting expedition, in a very remote range; the other was trapped

near the top of a high mountain.

Except in the depth of a very severe

winter, the wildcat seldom leaves its lone retreat. Nothing comes amiss to

it in the shape of prey; lambs, grouse, hares, are all seized with equal

avidity. The female fears nothing when in defence of her young, and will

attack even man himself. She generally rears them in rocky clefts and

precipices. I saw a couple of young ones that were killed in one of the

mountain cairns; they were nearly as large as a house-cat, although not many

weeks old. It was curious to see their short tails, and helpless, unformed

kitten look, contrasted with their size. Several attempts were made to shoot

the old one, but she was never seen; probably, upon missing her young, she

forsook the haunt.

The wild-cat has seldom more than three

or four young ones at a time-often only two. |