OCCASIONALLY, while ranging for roes, the hounds come on

the track of a hill-fox; they will then show even more than their usual

keenness, and open with greater ardour. As the same passes often serve for

both, the roe-hunter has sometimes an opportunity of shooting this wily

destroyer. Such a chance only occurs when prey is scarce on the mountains,

and he leaves them to seek it in the woods below; I therefore do not

recommend having a charge of smaller shot in one barrel-a plan adopted by

some.

Any one who sees the hill-fox bounding along within fair

distance, will immediately be struck with the difference of his appearance

from that of the small cur, which never leaves the low grounds. The

mountain-fox is a splendid-looking fellow ; even the sneaking gait of the

enemy of the poultry-yard has, in a great measure, left him ; he seems to

feel that he breathes a freer air,

and lives by more noble plunder. lie is extremely

destructive to all game within his range, and the havoc lie makes among the

hill-lambs is a serious loss to the farmer. He will also not unfrequently

attack and destroy full-grown sheep. To prevent the increase of these

freebooters, a man is appointed for each district of the Highlands, called "

the fox-hunter," whose business it is to search out and destroy the young

litters, in which he is ably seconded by the farmers and shepherds.

The place selected by the mountain-fox for rearing its

young is widely different from that of his pigmy relation of the Lowlands.

Unlike the latter, who chooses an old badger-earth or drain, in the midst,

perhaps, of a pheasant preserve, the hill-fox prefers some wild and craggy

ravine, on the top or side of a mountain, far removed from the haunts of

men. In spring, these places are all narrowly searched by the shepherds, and

the den (for you cannot call the clefts of the rock an earth) often detected

by the quantities of wool, feathers of grouse, &c., scattered about the

entrance. These are the remains of prey brought to the young; for as soon as

they are able to eat flesh, the old ones leave them during the day, bringing

them food morning and evening.

When the litter is discovered, "the fox-hunter" is

brought into requisition (who often at this time has more calls than he can

answer) ; his terriers are sent into the den, and the young massacred; a

watch is then set to command a view all round, in order, if possible, to

shoot the old ones when they return. I have been told by people thus

employed, that they had no idea of the proverbial cunning of the fox until

they saw it shown upon such occasions. Although the place has been perfectly

bare, the old ones have come unperceived within ten yards of the party, and

were at last only discovered by the straining of the dogs on the leash. I

have often heard the watchers say, that the ease with which " the tod"

avoids their faces, and skulks behind their backs, is most surprising. If

the foxes escape the guns, as they commonly do, "the streakers" [A breed

between the largest size of greyhound and foxhound. Some of them are swift,

very savage, and admirably adapted for the purpose.] are slipped upon them,

and, if not then run down, nothing remains to be done but again to set the

watch. So long as the old ones are prevented from entering, they will return

morning and evening for several days ; but, should either of them get

access, and miss the young, they come back no more. At those times of the

year when there are no litters, the usual way of hunting is to place a man,

with a streaker or greyhound ready to slip, upon the tops of the

neighbouring hills ; the fox-hunter then draws all the corries, crags, &c.,

where they haunt. Should Reynard be started, he is almost sure to take a

course over the top of one of the hills where the men are posted. He comes

up all blown, and, if observed, (which, I must say, is seldom the case,) has

a fresh streaker slipped upon him, which ought to run him down.

I may here give an account of a hunt I had with one of my

brothers, after as fine a mountain-fox as ever prowled upon the wild moor.

We had gone on a roe-hunting expedition to a high and steep hill in

Dumbartonshire, the lower part of which was a larch and oak copse, the

centre a large pine-wood, and the top covered with long heather. After

choosing our passes between the pinewood and copse, we sent a first-rate old

hound to draw the latter; scarcely had it been in the cover ten minutes,

when it opened upon a cold scent, and continued puzzling for a considerable

time. As this was not its wont when upon a roe, we half suspected a fox:

presently the scent warmed, and in a short time the hound opened gaily. Our

hopes were high, as it came straight in the direction of our passes. In a

moment I heard my brother fire; and the baying of the hound ceasing shortly

after, I concluded the shot had taken effect, and walked off to see what he

had killed. When I had gone a little distance, I met him running and calling

to me to get into my pass again, as he had shot at an enormous fox in the

thickest part of the cover; and as it had doubled back, which had occasioned

the check, it would most likely try my pass next. I wheeled about at full

speed, and arrived just too late for a deadly shot. When within seventy

yards of the pass, the fox was bounding over the stone wall that divides the

copse from the pine-wood, and presenting his broadside, a very distant but

clear

and open shot. I discharged both barrels, and watched

narrowly to see if he was hit ; the ground was level for a short way, and no

abatement of his speed was perceptible ; but as soon as he began to climb

the hill, a labouring motion at once told that one of us had wounded him.

Without stopping to load, I ran to see if there was blood upon the grass,

and when thus engaged, the hound, which had recovered the track, came up

full cry. I had no choice left but to breast the hill, and, if possible,

keep within hearing of the dog. Panting and breathless, I could hear the bay

more and more distant, and was just beginning to fear that the fox's object

was the savage ravines of Glen-Douglas, when it ceased on a sudden.

Encouraged by the hope that he might be run down, I redoubled my exertions,

and after scrambling a mile and a half from where I fired, saw the hound at

check, at the top of the pine-wood where it joins the heather. I made

several unsuccessful casts above ; and then, thinking that, unable to climb

the hill, he had returned to the shelter of the wood, I was making a circle

below, when he sprung out of the heather, not thirty yards off, and ran

straight down the hill, his lagging and staggering gait showing that he had

got his death-wound. I would now have given a good deal had my gun been

loaded ; but not a moment was to be lost, as the hound viewed the fox, and

was again full cry. I dashed over stock and stone, but it was not long

before there was another pause in mid career. When I came up, the ground was

perfectly bare, not a furze-bush to cover a rat, and the hound completely at

fault. I had just taken out my powder-flask to load, when, from no other

concealment than the bare stem of a fallen fir-tree, the fox a second time

burst out, as fair a shot as I could wish. The hound was close to his brush,

so back went my powderflask into my pocket, and I rushed down the steep with

reckless desperation. The bay became fainter and fainter; my head grew

dizzy; I had run a distance of three miles on one of the steepest hills in

Scotland, and had just given up hope of another check, when I heard a

woodman's axe. More by signs than words, I made him comprehend that he must

follow the dog as long as he was able ; sat down to rest for a moment, and

then loaded my gun. No sound was now to be heard; the whole wood seemed as

if it had never been disturbed. I shouldered my gun, and was proceeding, as

I thought, in the direction of the chase, when I met my brother, who had

from the first taken a different route, in order to intercept the fox at

another point. We proceeded together in search of hound and woodman, but for

a long time unsuccessfully ; at last we thought of returning to the place

were I first found him at work. Our delight may be imagined, when we saw the

hound tied up, the woodman smoking his pipe, and the fox lifeless on the

ground, a perfect monster. The man's account was, that after following a

considerable way, and being nearly distanced, there was a sudden check; when

he came up, he found the fox dead, the hound standing over him, without

having touched a hair - he had run till his heart was broken. We sent this

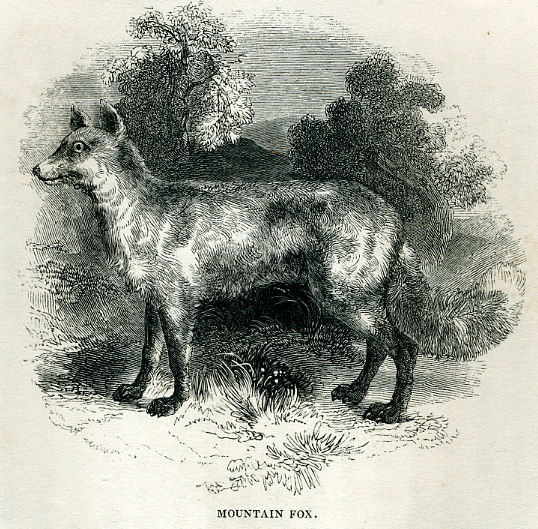

magnificent fox to be stuffed at the College Museum, Glasgow; those who had

charge of it told us they had never seen one nearly so large, and many who

came on purpose to see it were equally astonished at its size. It is now in

my possession ; and the woodcut shows most correctly the difference between

it and a very fine specimen of the poultry-fox, shot in my brother's

preserves. The brush of the larger fox is not longer than that of the

smaller, and less white on the tip, but it is uncommonly thick and bushy. He

stands very high upon his legs, which are exceedingly muscular; his head is

very broad, and his nose not nearly so peaked as the other's ; his coat is

also much more shaggy, and mixed with white hairs - an invariable mark of

the hill-fox, and which makes his colour lighter and a less decided red than

the fox of the Lowlands.