|

I

HAVE often thought that for those who have a

taste for deer-stalking, without the opportunity, it might be no bad

substitute to have a flock or two of goats upon a remote range of hills. The

idea suggested itself to me from having heard and seen a good deal of the

nature and habits of a few kept wild upon an island on Loch Lomond. These

goats, originally a breed between the Welsh and Highland, were very large,

and the oldest inhabitant does not recollect when they were first

introduced. After having been completely left to themselves for a few

generations, they became very cunning and suspicious, always haunting the

most out-of-the-way craggy places they could find, and one precipice in

particular has been called from time immemorial Crap-na-gour, or Hill of the

Goats. The breed has now very much deteriorated, from the fine old wild ones

having been killed off, and a number of the tame kind lately substituted.

The hair of some of the old "Billys" of the wild breed was eighteen inches

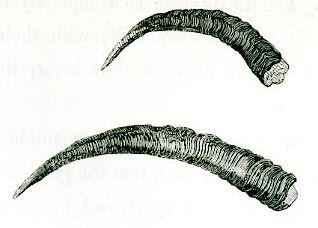

long ; and I have contrasted a horn of the last fine specimen of the race,

shot many years ago, with a good-sized one of the domesticated species. To

stalk these half-tame goats afforded no small diversion, and I have seen

several sportsmen engaged nearly a whole day before the fatal shot was

fired. But in their wilder state, I am told, they showed amazing game, tact,

and cunning in eluding an enemy. The hero, whose horn I have represented,

managed to escape several of the most experienced hands in the country, some

with ball and others with buck-shot, for a couple of days. He was brought

down on the evening of the second day, after being hard struck a short time

before; and I have been assured that even larger than he have been killed

upon the island, with horns proportionably finer.

Another circumstance also made me

imagine that goat-stalking might be practicable. One of my father's tenants,

who farmed the remote range of Glen-Douglas, had a flock of goats pastured

among the precipices. This flock was always under the command of the

shepherds and their dogs. A fine old Billy, however, broke away from the

rest, and spurned all control. This lasted upwards of a year, when he became

so completely wild that it required half a dozen shepherds, with their guns,

to range the mountains for some days before he could be shot.

I am aware that many objections might

be raised against my suggestion; first, that the goats would never be wild

enough to afford sport, and that, if they were, they would be apt to take

refuge among inaccessible rocks and precipices, where no man could stalk

them. I own that it would be many years before goats could become quite

wild, but if a fine breed were turned out on some of the steepest and least

frequented of our mountains, and especially if they were never disturbed or

brought to bay by dogs, I have no doubt that their progeny would

become fit for stalking. And as to sheltering themselves in rocks and

precipices, they would be far less apt to do this when they had acquired

confidence in other means of escape. I only, however, mention goat-stalking

as an untried amusement, and think it might be worth while for the

proprietors of Highland mountains to make the experiment. Sheep-farms, where

deer never remain, would answer for the purpose. The goats do not interfere

with the sheep, and generally choose the roughest ground where the pasture

is of least value. It is unnecessary to say that the old Billys would be

uneatable, but the mountain-fed kids are reckoned very delicious.

|