|

This first of British sports can only be enjoyed by the

few Highland proprietors who still maintain their forests, and those to whom

their permission is extended. Still if the many keen sportsmen who are

panting to try their rifles upon a gallant stag were thoroughly entered at

deerstalking, they might find less cause to regret their privation than they

now imagine. In the first place, no sport is more ruled by the weather:

again, one is so dependent on the skill and tact of the stalker, in whose

hands, for some time at least, you must be content to act like a mere

puppet. And when the deer are driven, a single false move, or the mistaking

of a signal by the hill-men employed, may spoil all. In every other kind of

shooting, the sportsman ought to trust to his own resources and foresight;

but in deer-stalking, unless he has passed his life in the forest, and is

thoroughly acquainted with every corrie, crag, and knoll, he had much better

trust to those who are. Without this knowledge it is impossible for any one

to tell how the wind will blow upon a given point: sometimes it may be north

on one side of a hollow and south on the other ; and I have seen the mist

moving slowly in one direction along the hill-side, and half an hour

afterwards the very reverse, without any change in the wind. To account for

this on the spur of the moment would often puzzle the scientific, but the

unlettered hill-man, who has only been taught by the rough experience of the

crag and the blast, though unable to talk theoretically on the subject, yet,

from constant and acute observation, will confidently predict the result;

and, taking advantage of every shifting change, bring you within fair rifle

distance of the unsuspecting herd.

To a novice, even though an expert rifle-shot, the first

sight of "the antlered monarch of the waste" will almost take away the power

of hitting him. But to any one accustomed to the sport and constantly

practising it, the sameness abates somewhat of its intense interest: for it

admits of no variety but the age and dimensions of the stag. In wild-fowl

shooting the excitement is kept alive by the various kinds of game that

present themselves, from the magnificent hooper to the tiny teal. On the

grouse mountains there is often the uncertainty whether the next point may

be the red or the "jetty heath-cock," or whether a twiddling snipe may

spring, or an Alpine hare start unexpectedly before you. It is the same

uncertainty which gives zest to cover-shooting. The golden-breasted

pheasant, the russet woodcock, the skulking hare or dodging coney, may all

successively appear.

I do not mean by the above remarks to depreciate

deer-stalking. It is sport for princes. I only offer them as consolation to

those who undervalue the amusement within their reach, by exaggerated ideas

of that above it.

No man with good nerves need despair of becoming a

tolerable rifle-shot, as the great art is to take plenty of time ; in fact,

to shoot as coolly at a deer as at the target. The American backwoodsmen

with their ill-balanced rifles can hit the jugular vein of an animal feeding

or moving about, with unerring accuracy, at thirty or forty yards. Every one

must see how much this depends upon nerve and coolness, and these settlers

are taught the self-command, which is the basis of their dexterity, from

their earliest years. I recollect being shown, by the owner, a rifle which

he considered a chef-d' oeuvre of American workmanship. The most

cool-headed forester of our country would have been puzzled to do much

execution with it at first. It looked and felt exactly like a toy, with its

peaked and silver-mounted toe and heel-plate, long unbalanced barrel, and

ludicrously small bore. Our rifles, on the contrary, are beautifully poised,

and their weight enables us to take a much steadier aim at a long distance,

when the ball, from being much larger, is less affected by the wind. I dare

say, however, if a highland deer-stalker and American wood-ranger, both

finished adepts in their own way, were fairly matched, each would have a

sovereign contempt for the dexterity of the other.

I have constantly observed that the performers most to be

depended on with the rifle are what are called "poking shots;" for although

the first-rate hand with the fowling-piece may often bring down the deer

running in admirable style, yet upon any unexpected fair chance presenting

itself, he is apt to fire too quick, forgetting the different style of

shooting which is required for a rifle; while the slow man, however taken

unawares, always gives himself time for deliberate aim. Any one, also, who

has been practising much at snipe, or other quick shooting, will, unless

quite on his guard, be almost certain to miss the deer until his hand is

brought in, after which, when he again returns to the snipe, they will stand

a better chance of escape, from the poking manner in which he will at first

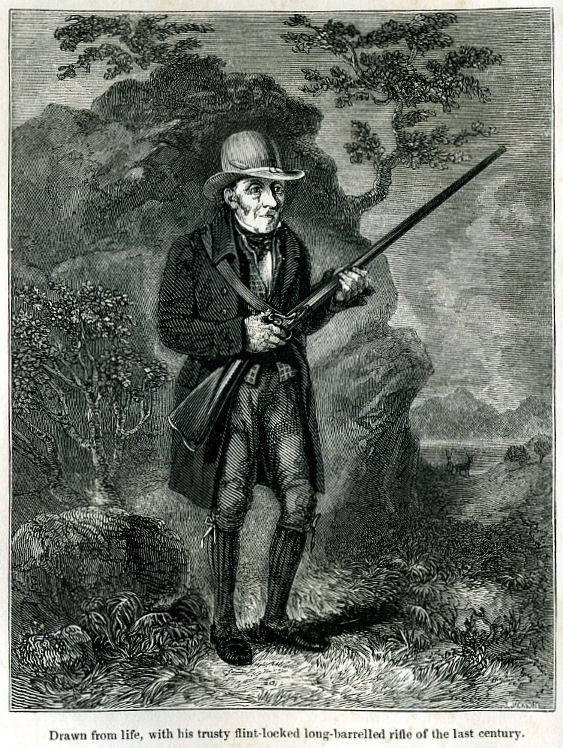

be inclined to fire at them. As a boy, I remember being much perplexed to

see a gamekeeper miss a fair shot at a deer, when a few days before he had

killed seven swifts out of eight flying past at "full bat;" while his

father, the old forester whose likeness I have given, could scarcely have

touched one, and yet seldom missed a rifle-shot. There was another man who

generally accompanied them in their stalking expeditions, and whose shooting

was a still greater puzzle. Although not left-handed, he shot from the left

shoulder, being unable to close his left eye, and was as slow a performer as

ever pulled a trigger. Flying shots he invariably missed, and, at last,

seldom fired at; but ground game, except rabbits, had no chance with him.

Nothing could flurry or put him out of his shooting. If the shot was not

intercepted, and he was only allowed plenty of time, it was certain death.

I had twice an opportunity of seeing these three men

fairly tested with the rifle. Some deer being discovered near the top of a

high hill, it was arranged, as all their passes were well known, to drive

them with some shepherds and their colleys. My brother and I begged hard to

join the party, and were placed under charge of the gamekeeper, whose pass

was one of the best. Before starting, however, the left-shouldered man

wished to fire off an old load, being afraid to risk it at the deer. It was

suggested that he should shoot at a hare. We had not gone far when one rose

about forty yards off. Even now I think I see the cool way in which he

raised his rifle, and, allowing poor puss a free stretch of thirty yards,

fired. The hare dropped dead, and, when we went up, she was fairly struck

between the shoulders. After a time we were safe in our passes, and the

driving-party commenced their manoeuvres. We soon heard the yelp of the

dogs, and, shortly after, the floundering of a deer in some mossy ground

immediately above the pass. Presently it made its appearance, crossing us at

about sixty yards' distance. It was a beautiful chance. Taking deliberate

aim, the gamekeeper fired. To our astonishment and chagrin, the deer which

had been moving slowly along, bounded forward, frightened enough, but

unhurt. No other chance was obtained till near the end of the day, when the

old forester fired a tremendous long shot, and struck the deer, which ran

for a few hundred yards, and then dropped.

Another time, when the deer had taken the water, there

was a general scramble to the shore; a boat was quickly procured, which the

cunning animal no sooner saw bearing down than it turned short round, and

was within a few yards of grounding, when the three aforesaid stalkers were

ready to fire within fair distance. The left-handed man took deliberate aim

at the head, the only part above water, and cut off the horns close to the

skull. The deer now struck ground, and when bounding along the shore was

missed by the gamekeeper, but immediately brought down in admirable style by

his old father. That a man could miss a deer, and yet knock down double

shots one after another at game, used to appear a complete problem to me ;

especially as one of his rivals could not hit a bird at all, and his father

as a game-shot was not to be named in the same day with him. After a little

practice myself, the solution was plain, I have seen this old man in his

eightieth year, bring down a deer running, and last season had some

venison sent me, killed by him, when ninety-one years old!!

As I consider this forester the finest specimen I ever

met with of a Highlander of the old school, I may perhaps be allowed to

mention some of his peculiarities apart from his professional avocations.

His words like his shooting are slow, but sure to tell. When addressing his

superiors, his manner is marked by the greatest courtesy, without the least

approach to servility. He is well read in ancient history, knows all about

the siege of Troy, and talks with the greatest interest of Hannibal's

passage over the Alps. On one occasion, when several gentlemen were talking

on a disputed point of history, he stepped forward, begged pardon for

interrupting them, and cleared it up to their utter amazement. His memory is

still excellent, and nothing gives him greater delight than old traditions,

legends, &c. The last time I saw him, he gave us an account of some of the

Roman Catholic bishops of Scotland with characteristic anecdotes. In

politics he has his own peculiar opinions, is particularly jealous of the

encroachments of the "Great Bear" as he calls Russia, and thinks the allies

committed an irreparable error in not partitioning France after the battle

of Waterloo. No present finds greater favour than the last Newspaper; and it

is curious to see the old man devour in its contents without spectacles. He

would not be a true Highlander were he not a firm believer in all their

superstitions. Two instances of second-sight he related to me as having

happened to himself; although he is very unwilling to talk upon the subject,

and I have often noticed his evasive replies to those who questioned him. I

premise my account, by saying, that wherever he is known, his word has never

been doubted, and I would believe it as implicitly as that of the proudest

peer in the realm. One day, when returning very tired from some sporting

expedition, he met an acquaintance, accompanied by a young man whom he also

perfectly well knew. The first stopped to ask "what sport;" he gave a short

answer over his shoulder, and saw the young man walk on. That afternoon he

heard he had been killed by a fall from his cart, at the very time of this

rencontre. Upon questioning his companion the next day, he said there was no

person with him. The other instance happened one rainy evening when looking

over his kennel. He saw a man with a grape cleaning out the gutter, and

called to know who had desired him to do so. The gutter-cleaner walked

slowly towards him, but something having arrested his attention in the mean

time, he lost sight of him, and could not make out how he had disappeared;

upon inquiring of the overseer, he said this man was unwell and confined to

bed. He shortly afterwards recovered, which was sufficient confirmation to

the old forester of the truth of his vision, for in all cases of

second-sight, where the object approaches, it is a sure sign of recovery,

and when it recedes, of death. Another of his prejudices is the lucky or

unlucky "first foot." Half the people of the country were one or the other

with him. There was a canty old carle of a herd whose happy cheerful face

was enough to banish care from every other brow; but the old forester had

unfortunately met him on the morning of some unlucky day. Now as it happened

that this conscientious old herd, whose boast it was "I never did ahint ma

maister's back what I wad na do afore his face," was generally one of the

earliest astir; he was oftener the "first-foot" than any other body, and as

he came crooning some old Gaelic song, with his staff over his shoulder, and

gave his blithe salutation, "Goot mornin, goot mornin; goot sport, goot

sport!" a stranger would wonder at the look of gloom which overshadowed the

forester's face, and the scarcely articulate grunt which was his only reply,

sometimes followed by the half-muttered exclamation, "Chock that body!" To

shoot a wild-swan was reckoned a most unlucky feat. One severe winter, when

after water-fowl with another man, four hoopers were discovered close to the

shore. His companion eagerly pointed them out, when the old forester, who

had most likely seen them first, coolly replied, " You see, John, we'll just

let them alone! The only thing not truly national about him was substituting

a pinch of snuff for a quid of tobacco, and when out on the hills he has

often expressed his belief, that the moss-water he was sometimes obliged to

drink would long ago have been the death of him had he not always followed

it up by the antidote of a pinch which "killed all the venom." But the

character of my old friend has beguiled me into too long a digression. I

must now return to the rifle.

Every man before firing at deer must be thoroughly

acquainted with his own, a point even more important with a rifle than a

shot-gun. Under eighty yards, it will most likely shoot a little high; and

if the wind is at all strong, it will alter the direction of the ball fully

a foot at a hundred yards, for which allowance must be made. The best place

to hit a deer, unless he is lying down, and so close as to tempt one to try

the head, is just behind the shoulder. If struck fair, he will most likely

bound forward ten or twenty yards, and then drop. One that I shot ran fifty

yards before it fell, although the lower part of the heart was touched. When

this occurs, you may be sure it will never rise again. If, on the contrary,

it falls instantaneously, unless shot through the head, neck, or spine, it

may very possibly spring up on a sudden, and perhaps escape altogether. If

struck too far back, a deer may sometimes run for half a day, and the wound

has even been known to heal up, but is more likely to prove fatal the next

day. When a deer is discovered lying down, in such a situation that he might

dip out of sight the moment he rises, and only his horns visible, the

sportsman should advance with extreme caution until the deer hears him, when

he will most likely slowly raise and turn his head before springing up. Now

is the time to shoot him between the eye and the ear.

The most propitious day for deer-stalking is a cloudy one

with blinks of sunshine ; exactly such as you would choose for fishing. When

the sky is cloudless, and the sun very dazzling, the herd are apt to see you

at a great distance, and take alarm. High and changing wind is always very

bad, as it keeps them moving about in a wild and uneasy state. In such

weather it is better, if possible, to wait till it settles a little, and

take advantage of the first calm. If the breeze be light, they will not move

much, but a strong steady wind lasting for some days will always make the

deer change their ground, by facing it often for miles. Mist is the worst of

all, as the deer are pretty sure to see you before you see

them. Always advance on deer from above, as

they are much less apt to look up than down a hill. If possible, have the

sun at your back, and in

their face. With this advantage you may even venture to approach

them from below. (Birds, on the contrary, always look up, and it is best to

stalk them from lower ground.) If it is a quiet

shot, and the sun is at your back, wait for a clear blink before making your

near approach. Of course every one knows, that it is out of the question,

under any circumstances, to attempt advancing

on deer unless the wind be favourable, so all other directions are subject

to this.

In corries and hollows it is quite impossible to know how

the wind will blow upon a particular point, unless you

have marked every change of wind upon every point of the corrie.

The quick sight of a skilful forester in first

discovering deer will appear miraculous to a stranger to the sport, and

unless quite bewildered, he cannot fail to admire the generalship which

follows. The whole ground is as perfectly known to his guide as his own

pleasure-grounds to himself. Every hollow, every knoll, is taken advantage

of; every shifting turn of the wind, up the one or round the other, is

surely predicted, until, to his own utter amazement, the panting Sassenach

or Lowlander is told that he is within fair rifle-distance of a bevy of

noble harts.

After deer have been stalked and shot at, they become

much wilder ; the best sport at the old harts is therefore obtained at the

beginning of the season. They generally keep together, and when their

stately mien and branching antlers are seen in the distance, it is enough to

inspirit the most apathetic ; but when told to cock his double-barrelled

rifle for a shot, I could well excuse a novice for being scarcely able to

obey. When there are hinds in the herd they often present themselves between

you and the unsuspecting harts ; but even should they be at a distance,

great caution is necessary, as, if one hind gets a glimpse of the crouching

enemy, the whole herd, stags and all, are sure to scamper away, amidst the

bitter execrations of the forester upon its hornless head.

The next best time for a shot at a fine old stag, after

they have become wild, is about the beginning of October, when each lot of

hinds is sure to contain a good hart. The chances then may often not be so

good, but from the stags being dispersed, there are more of them. If deer

are feeding forward, it requires very nice calculation, when at a distance,

to know the point they will arrive at, by the time you have neared them,

especially as a shower of rain or a gust of wind will quicken their motions.

But if the stalker is not far from the herd, which is feeding up to his

place of concealment, with a favourable wind, he should not grudge waiting ;

for, by sending round drivers to windward of the deer, they are often apt to

turn and face them. I can't say that driving, under any circumstances, gives

half the pleasure that stalking does; for my own part, I would rather kill

one stalked hart than several driven. Driving, however, upon a large scale

has a most imposing effect, and, although it cannot be otherwise than

injurious to a forest, yet the exhilarating nature of the whole proceedings,

in which so many friends may join, often makes the proprietor overlook the

consternation and panic it creates among the wild and timid herd. Some part

of the forest is selected to which the deer are to be driven; a great number

of hill-men and shepherds, who thoroughly understand what they are about,

are then sent to the furthest extremity to bring all the deer they can

collect to this spot; the passes, of course, being well known, are occupied

by the sportsmen with their rifles. The drivers sometimes hallooing, and

sometimes giving their wind, gradually contract their circle, the deer are

huddled together, and finding the only clear ground in the direction of the

rifles, slowly and cautiously take their doomed way. There is often great

difficulty in driving them, as they are always obliged to go with the wind,

which their natural instinct of self-preservation makes them very unwilling

to do, and, if they possibly can, they always face it. When the herd come

within distance of the rifles, great mischief often ensues ; the nervous and

indifferent shot firing into the centre of the living mass, while even the

experienced deer-stalker, in singling out the stag-royal, may sometimes

wound a couple of hinds beyond him.

So much for driving on grand occasions, which gives the

shooter a tolerably snug sinecure until the game comes up to his hand. But

when it is practised in a small way, there is no sport which more calls into

play his pluck and endurance of fatigue. He first climbs to the ridge of the

hill, where he is at once seen by the hawk-eyed driver who has taken his

station near the foot, or on the opposite brow, and marked with his glass

every herd at feed or rest on the face below. As soon as he has selected

one, he attempts to drive it up the hill, towards the sportsman, either by

hallooing or showing himself; at the same time giving warning by the manner

of his halloo which way they are likely to take. The sportsman must be

thoroughly acquainted with all the passes, or have some person with him who

is ; and, running from one "snib" to another, in obedience to the signal

below, catch sight of the horns of the herd, as, with serpentine ascent,

they wind their wary way. From the zigzag manner in which they often come

up, it is very difficult to make sure which pass will be the favoured one,

and I have been within a few hundred yards of the antlers when the prolonged

shout from below has warned me that I had an almost perpendicular shoulder

of the hill to breast at my utmost speed before I could hope to obtain the

much-desired shot. If the wind is at all high, so determined are the deer to

face it, that, unless there are a great number of drivers, one herd after

another may take the wrong direction, but, if the day is favourable, with

only a light breeze, a knowing driver or two will generally manage to send

them up to the rifle. When the deer have selected their pass, should you be

within fair distance, with both barrels cocked, beware of making the

slightest motion, especially of the head, until you mean to fire. Even when

perfectly in view, if you lie flat and don't move, the herd are almost sure

to pass. One or two hinds generally take the lead. The fine old harts, if

there are any in the herd, often come next, but sometimes, if very fat and

lazy, they lag in the rear. When the first few hinds have fairly passed, the

rest are sure to follow, until their line is broken, and their motions

quickened by a double volley from the rifle.

When stalking last September in Glenartney forest by the

kind permission of the noble owner, I had as fine a chance as man could wish

spoiled by the scarcely audible whimper of a dog. I was placed in a most

advantageous spot, within near distance of the pass. Presently an old hind

came picking her stately steps, like a lady of the old school ushering her

company to the dining-room. Next her came a careless two year-old hart,

looking very anxious to get forward, and perfectly regardless of danger. All

was now safe, I felt sure of my shot; when, horror of horrors! a slight

whimper was heard. The old hind listened, halted, and then turned short

round upon the young hart, who instantly followed her example, and the whole

herd ran helter-skelter down the hill. The unfortunate sound proceeded from

one of the forester's two colleys, the only dogs Lord Willoughby allows in

the forest ; they are kept for the purpose of bringing to bay any deer badly

wounded, and are never slipped upon other occasions. The mar-plot above

alluded to is an old dog, and very good for the purpose ; he had winded

without seeing the deer--hence his mistake.

Glenartney is a beautiful little forest, walled round by

fine green hills, but the deer being too numerous for its extent, are rather

small. It also stands high, and is not so well sheltered as might be

desired, on which account the deer, when the winter storm sets in severely,

although fed to the full, cannot remain to eat their food, and are obliged

to seek the shelter of the woods for many miles round, far beyond their

bounds. At night they wander to the turnip-fields for sustenance, where

numbers are shot by poachers, who watch the gates and openings into the

fields. One man boasted to me that he had in that manner killed six during

one storm, with a common fowling-piece loaded with ball. The turnip-field

where he performed this feat was more than twelve miles from the forest.

Perhaps as fine deer as any in the kingdom are those of

the Black Mount. The cup [The three top prongs of the horn, growing out

together, form a cup. There is no cup at all except in the finest and oldest

stags.] on the top of the horns of many, according to Highland phrase, would

hold a gill of whisky ; and yet there are heads now preserved in Taymouth

Castle which show that their forefathers, though fewer in number, were even

greater than they. The Black Mount is twenty-one miles long by twelve broad,

and the Marquis of Breadalbane, notwithstanding his numerous engagements in

public life, has not neglected this noble appanage of a Highland proprietor.

No expense or trouble is spared which can contribute to the winter

subsistence of the deer, or protect them from poachers. Patches of different

kinds of food are sown in the valleys, and left uncut, to which they flock

during the severity of winter. The forest has plenty of green summer food,

and abundance of long heather, which affords shelter in cold weather, and is

greedily eaten in the snow-storm, when hardly any other food can be reached.

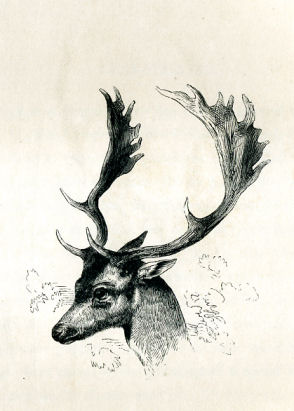

I shot the subject of the wood-cut there about the middle of last October,

when the forest was in all its glory, and nothing but sounds of rivalry and

defiance were heard in every quarter. The head is not by any means the

largest size, but may be taken as a fair average specimen. The fallow-deer's

head was from life, one of the finest I ever saw.

The day I shot the red-deer was perhaps the most

unpropitious for stalking which could possibly have been chosen. In the

morning, the mist was rolling lazily along the sides of the mountains, in

dense masses, and it was evident there would be rain before the close of the

day. It was enough to damp the heart of the most ardent deer-stalker, but I

determined (having little time to spare) to abide by the forester's opinion.

His answer was, that "we would just do our best; but if we were unsuccessful

to-day I must e' en wait for to-morrow." With this determination we started

for the forest, followed by an under-keeper, with one of Lord Breadalbane's

fine deer-hounds, led in a leash. A slight breeze at first sprung up, and

partially cleared away the mist from some of the lower hills. The quick eye

of Robertson immediately discovered a deer lying down upon the ridge of one

of them. His glass was instantly fixed. "There, Sir, if you could manage

that fellow, you would have one of the finest harts in the forest." "Well,

suppose we go round by the back of the hill, and come down that hollow, we

should be within fair distance from the rock." "If he'll only lie still, and

give us time enough." This however the stag had determined not to do, for

when we came to the hollow, he had risen from his rocky couch, and was

immediately detected by Robertson, quietly taking his breakfast, among his

hinds, a considerable way below.

The place was so open all round that it was impossible to

get near him, and the mist soon afterwards came on so thick that we only

knew that the deer were all round us by their incessant bellowing. The

forester looked much disconcerted, for, in addition to the mist, a drizzling

rain began to descend. We sat down behind a hillock, and I desired the

under-keeper to produce the provision-basket. "If there was only a breeze,"

says Robertson, "and I do believe it's comin', for the draps o' rain are

much heavier." And so it proved, for the mist again partially cleared. We

hastened to take advantage of the change, and Robertson, ten yards in

advance, mounting every knoll and searching every hollow with an eye that

seemed to penetrate the very mist, suddenly threw himself upon the ground,

and signalled us to do the same. A roar like that of a bull presently let us

know the cause, and on a little amphitheatre about five hundred yards off,

his profile in full relief, stood as noble a stag as ever "tossed his beamed

frontlet to the sky." There he was, like knight of old, every now and then

sounding his trumpet of defiance, and courting the battle and the strife.

Nor did he challenge in vain, for while we were admiring his majestic

attitude, another champion rushed upon him, and a fierce encounter followed.

We could distinctly hear the crashing of their horns, as they alternately

drove each other to the extremity of the lists. "I wish the ball was through

the heart o' one o' ye !" muttered the under-keeper. His wishes were soon to

be realized, for the younger knight, who seemed to have the advantage in

courage and activity, at last fairly drove his adversary over the knoll and

disappeared after him. Robertson now rushed forward signing to me to follow,

and peeping cautiously over the scene of contest, slunk back again, and

crawled on hand and knee up a hollow to a hillock immediately beyond: I

following his exemple. When we had gained this point, he took another wary

survey, and whispered that the hinds were on the other side of the knoll

within thirty yards. It was now a nervous time, but I could not help

admiring the coolness of the forester. Without the least appearance of

flurry, he had both eyes and ears open, and gave his directions with

distinctness and precision. "That will do; there goes a hind, the whole will

follow. Place your rifle on that stone, you'll get a famous chance about

eighty yards." - "He'll come at last," he again whispered, as hind after

hind slowly passed in review, when a roar was heard immediately below us.

"As sure as I 'm leevin' he's comin' on the very tap o' us. Hold the rifle

this way, Sir, and shoot him between the horns the moment his head comes

ow'r the knowe." I had scarcely altered my position when head, horns and all

appeared in full view. Seeing us in a moment, he was out of sight at a

bound, but taking a direction round the base of the hillock, presented his

broadside a beautiful cross-shot. I had plenty of time for deliberate aim,

and the Red Knight of the Wilds lay low and bleeding.

It was now nearly four o'clock, and the forester had some

doubts whether we could get to Inveroran that night, but as I was anxious to

start early in the morning, we despatched the follower for a cart, and with

great difficulty dragged the stag by the horns down the hill to the road.

Notwithstanding the weather, I had been delighted with my expedition, and

only regretted having killed the younger and victorious champion instead of

his more bulky rival. During our walk to the inn, I had many anecdotes of

former bloody deeds in the forest from Robertson, and not a few where the

balls had flown scatheless. One, in particular, amused me. The marquis,

accompanied by two friends, one of them, I should imagine, more famous for

his scientific than sporting qualifications, were stalking some very fine

harts. When within rifle-distance, his lordship and one of his friends were

crawling over a knoll, in order to select the best of the lot. "What are

they about up there?" said the virtuoso. "There are the deer." Bang!

bang! Off went the harts in a twinkling, wishing, I have no doubt, that they

had always such fair warning when danger was near.

We passed, during the day, several forest-baths, in full

use; i, e, moss-holes where the stags plunge up to the neck and roll

about to cool themselves, in summer and autumn. When they come out again,

black as pitch, they look like the evil genii of the mountain. In former

times poachers used to fasten spears with the points upward in these places,

and when the stag threw himself into the hole, he was impaled.

Lord Breadalbane has a very fine kennel of dogs,

exclusively for bringing the wounded deer to bay. They are for the most part

a breed between the foxhound and greyhound, but some are between the

deerhound and foxhound. The former are reckoned the best winded. The

forester is justly proud of these dogs, mentioning that some of them, when

chasing a cold (unwounded) hart with hinds, were so knowing, that, should

the hart give them the slip at a burn, and run down it, they would stop

their pursuit of the hinds, recover his track, and hold him at bay all night

should no one come to their relief. The cunning of the old patriarchs of the

forest is also remarkable. Once, when some young dogs were being entered at

the two-year-old harts, a stag-royal presented himself, but, seeing he was

not the immediate object of pursuit, he witnessed the whole chase from the

shelter of a plantation, and, when the foresters returned, they again

started him, close to where he was first put up, when he dashed into the

thicket of the wood. There was a tame one kept at one of the shooting-lodges

which attacked every one but the foresters, and at last was removed to the

park at Taymouth. This fellow became so savage and expert with his antlers,

that he killed, I have been told, two horses, and no one dared to pass his

haunt unless he knew them. |