|

MY advice on the subject of dogs must begin with the

caution, never to lay too much stress on their general appearance. For my

own part, I must confess that I am not very partial to the exceedingly

fine-coated, silken-eared, tobacco-pipe-tailed canine aristocracy; for, even

if their noses and style of hunting be good, they are invariably much

affected by cold and wet weather, and can seldom undergo the fatigue

requisite for the moors.

The most necessary

qualifications of a dog are travel, lastiness, and nose. The two first are

easily ascertained; but the other may not be found out for some time. I have

seen dogs shot over for a season without committing many mistakes, and on

that account thought excellent by their masters : their steadiness of course

has been shown, but they have given no proof of first-rate nose. Even a good

judge may be unable to form an accurate estimate of a dog's olfactory powers

until he has for several days hunted him against another of acknowledged

superiority. The difference may then be shown, not by the former putting up

game, but by the latter getting more

points. Should there be no tip-top dog at hand to compete with, the only

other criterion, though not at all an infallible one, is the manner of

finding game. The sportsman must watch most narrowly the moment when the dog

first winds: if he throws up his head, and moves boldly and confidently

forward, before settling on his point, it is a very good sign ; if, on the

contrary, he keeps pottering

about, trying first one side, then another, with his nose sometimes close

upon the ground, even though at last he comes to a handsome point, I should

think it most probable that he is a badly-bred, inferior animal.

Of all dogs, the worst for the moors

is what is called a near ranger. Such flinchers may do well enough in

preserved partridge ground, but on the steep hill it is quite sickening to

see their everlasting canter fifteen or twenty yards on each side. The

dog-breaker may say that although the dog ranges near, he is working as hard

as his more high-mettled competitor. For my own part, I never saw one travel

in that way that either worked so hard, kept it up so well, or

found half as much game as a

free-hunting dog.

Let your pointers be

first-rate, and a couple will

then be quite enough to hunt at a time; more only encumber. [The

only way to hunt two couple of dogs at the same time, without risk of

slacking their mettle, or otherwise spoiling them, is for each couple]

If well broke, they will not pass over the near to be commanded by a

separate keeper, and at a sufficient distance apart to prevent interference.

The sportsman can thus move from one to the other, as they find game. I,

however, always prefer hunting my own dogs, and never suffer them to be

spoken to by any one until I have fired, when I trust to my man to enforce

the "down charge" without noise.] game, and

when birds are scattered (the only time when the near-ranging potterers

are in their element), will find them one by one, with equal certainty

and greater despatch. Many gentlemen, however, take no trouble about

procuring good dogs, until just before the season begins, and consequently

must put up with inferior ones, in which case they are forced to hunt three

or four together, or have little chance of finding game. And a most

vexatious thing it is, after all, to see these cross-bred ill-broke curs

uniting their efforts to annoy;-one putting up birds, another finding none,

while a third contents himself with admiring the feats of his companions !

"What's Bob doing?" "Nothing." "What's Don doing?" " Helping Bob!!" Aware of

what he has to expect should he be unprovided, the knowing man of the moors

has always as many good dogs as he can work himself, and never

suffers them to be hunted or shot over by another.

The purchaser, before taking the

trouble to try a dog, should make sure that he has a hard round foot, is

well set upon his legs, symmetrically though rather strongly made ; but the

great thing is the head. It ought to be broad between the ears, which should

hang closely down; a fall in below the eyes; the nose rather long, and not

broad; nostrils very soft and damp. If these points are attended to, the dog

will seldom have a very inferior nose. The above remarks relate principally

to pointers, as I greatly prefer them to setters; but if the sportsman has a

scanty kennel, I should rather recommend the latter, as they are often

capable of undergoing more fatigue, and not so apt to be foot-sore. For my

own part, however, I find the pointer so much more docile and pleasant to

shoot with, that I never use setters; concerning the choice of which, as

there are so many varieties, totally differing in appearance from each

other, it would be useless to lay down any rules.

Many gentlemen, when the shooting

season begins, are shamefully taken in by dog-breakers and others. Few are

aware how difficult it is to know a good dog before he is shot over. The

breaker shows his kennel, puffing it off most unmercifully. The sportsman

chooses one or two dogs that suit his fancy; they drop at the sound of the

pistol, and perhaps get a point or two, when birds are so tame that no dog

but a cur could possibly put them up. The bargain is struck, the dog paid

for; but, when fairly tried, shows his deficiency in finding game. I have

seen the breaker look round with an air of the greatest triumph if a hare

should start, and his dog not chase: this is what any man who under-stands

the elements of breaking, by a little trouble, and taking the dog into a

preserve of hares, can soon effect.

Other obvious defects, such as not quartering the ground,

hunting down wind, not obeying the call or signal, the veriest novice in

field-sports will immediately detect. It is not, however, with faults so

apparent that dogs for sale are generally to be charged. They are, for the

most part, drubbed into such show subjection, [Dogs of this kind remind me

of an anecdote I remember to have heard from a brother sportsman, but for

the truth of which I cannot vouch :Walking out with a high-broke pointer, he

suddenly missed him, when he presently espied him soberly and submissively

following the heels of an old Guinea-fowl, whose reiterated cry of "Come

back! Come back!" he had thought it his duty to obey !!] that the tyro

fancies them perfect, and only finds out their bad breeding and nose after a

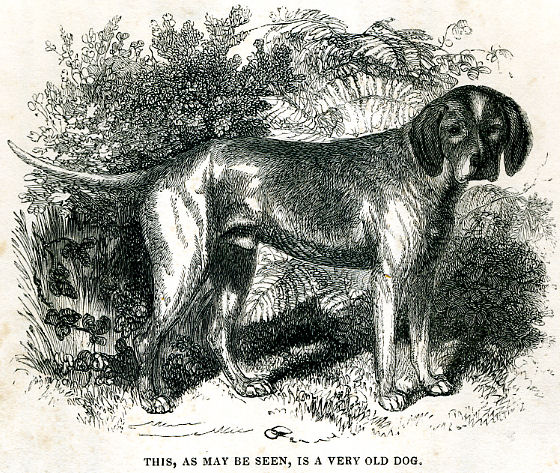

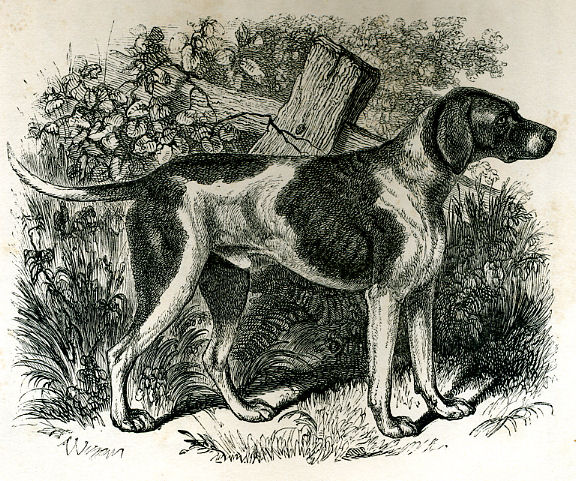

week's shooting. To assist the judgment of the uninitiated, I have given

accurate likenesses of the three best pointers I ever had. I know some

faults might be found in them, but they have all the main requisites.

If your dogs are well bred, the great secret of making

them first-rate on the moor is, never to pass over a fault, never chastise

with great severity nor in a passion, and to kill plenty of game over them.

There are two faults, however, to which dogs, otherwise valuable, are

sometimes addicted; these give the sportsman great annoyance, but may often

be more easily corrected than he is aware. One is the inveterate habit,

contracted through bad breaking, of running in when the bird drops. This

trick is acquired from the breaker's carelessness, in not always

making the dog fall down when birds rise, a rule which should never be

neglected, on any pretence. The steadiness of a dog, whether old or

young, depends entirely upon its being rigidly observed. After the fault

of running in is once learned, the quickest remedy is the trash-cord and

spiked collar; but many gentlemen buy dogs before shooting over them, and

commence their day's sport without these appendages. They are thus obliged

either to couple up the dog or run the risk of having any birds that remain,

after the pack has risen, driven up, and those that have fallen mangled by

him. I have seen dogs most unmercifully flogged, and yet bolt with the same

eagerness every shot. It was easy to see the reason: the dog was followed by

the keeper, endeavouring to make him "down;" there was thus a race between

them which should reach the fallen bird.

The plan to adopt with a dog of this description is, when

the grouse drops and the dog rushes forward, never to stir--coolly allow him

to tear away at the game until you have loaded ; by which time he will most

probably have become ashamed of himself. You will now walk up most

deliberately, and without noticing the bird take the dog by the ear, and

pull him back to where you fired,

all the time giving several hearty shakes, and calling "down." When you get

to the spot where you shot from, take out your whip, and between the stripes

call "down" in a loud voice ; continue this at intervals for some time, and,

even when you have finished your discipline, don't allow the dog to rise for

ten minutes at least; then, after speaking a few words expressive of

caution, take him slowly up to the bird and lift it before his nose. If this

plan is rigidly followed for several points, I never saw the dog that would

continue to run in at the shot.

The other defect is chiefly

applicable to young dogs; it is when they trust to their more experienced

comrade to find the game, and keep continually on the outlook expecting him

to do so. Nothing can be done for this but to pay the greatest attention to

their point; selecting it in preference to that of the other dog, and always

to fire, however small the chance of hitting the bird. Also change the dogs

they hunt with as often as possible. Young dogs, with this treatment, will

very soon acquire confidence, and never keep staring at their companion,

unless he is settling upon a point.

When the sportsman rears his

own puppies, he should be most particular, not only about the acknowledged

excellence of the sire and dam, but also that their breeding is

unexceptionable and well known-especially that there is no cross of the

rough, however remote, when breeding pointers, and no smooth blood when

setters are the object. It sometimes happens that a dog, though not well

bred, may turn out first-rate; but the progeny of such dog or bitch hardly

ever do. This double caution is therefore most necessary, as otherwise much

time and trouble might be spent upon a dog that never would be worth it,

from a mistaken idea, that as his parents were excellent, he must in the end

turn out well too.

To cross pointers and

fox-hounds, or setters and spaniels, for the sake of improving the noses of

the former or the travel of the latter, seldom answers. The one

qualification may be gained, but the dog generally loses in every other.

The essentials of

dog-breaking may be found in a pamphlet, published in London a few years

ago, by the gamekeeper of Sir John Sebright. Although not agreeing with it

in every particular, I certainly think it the best that has been written on

the subject. |