THE white hare inhabits many of our mountains. It is not

confined, like the ptarmigan, to the tops of the highest and most

inaccessible, but, on the contrary, is often met with on grouse-shooting

ranges, where there are few crags or rocks to be seen. I have frequently

shot it on flats, between the hills, where it had made its form like the

common hare; and, though I have more often moved it in rocky places-where it

sometimes has its seat a considerable way under a stone-I do not think it

ever burrows among them, as some suppose; for, although hard pressed, I have

never seen it attempt to shelter itself, like a rabbit, in that way. Indeed,

there would be little occasion for this, as its speed is scarcely inferior

to the hares of the wood or plain, and it evidently possesses more cunning.

When first started, instead of running heedlessly forward, it makes a few

corky bounds, then stops to listen-moving its ears about : and, if the

danger is urgent, darts off at full speed, always with the settled purpose

of reaching some high hill or craggy ravine. If not pressed, it springs

along as if for amusement; but takes care never to give its enemy an

advantage by loitering.

I put up one, on the 16th of last March, when inspecting

the heather-burning on my moor, which (contrary to their usual practice)

kept watching, and allowed me, several times, to come within a hundred

yards. I was at first surprised, but the explanation soon occurred to me

that it had young ones in the heather. I had thus a good opportunity of

noticing the commencement of its change of colour. The head was quite grey,

and the back nearly so ; which parts are the last to lose, as well as the

first to put on, the summer dress. I shot one nearly in the same stage, on

the 22nd of last November (183q). [I twice last autumn (1840) shot fine

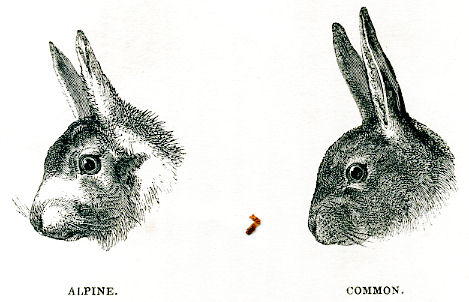

specimens of the alpine and common hare on the same day. The difference

between them, when thus closely compared, was very perceptible. The head of

the alpine was much rounder, which was rendered more obvious by the

shortness of its ears. The sent was also ludicrously small ; while the

roundness of the body was increased by the soft and very thick coat of fur,

which made that of the common hare appear hard and wiry. One of the alpine

hares was shot on the 17th of September ; there was not the least appearance

of the change of colour. The other, shot on the 6th of October, had a few

silver hairs about the toes. On the 11th I shot another which had the feet

and half the hind legs white, and was a little silvered behind the ears. On

the 2nd of December I shot another couple; the lower part of the body and

hind legs were like swan's down, the back and sides grizzled, and the only

unchanged parts were the' crown of the head and cheeks. The last day I went

after them was on the 15th of December, when I wished to ascertain whether

the change was quite complete. On that day I killed two hares and a leveret,

and was astonished to find that one of the former was in the same stage as

those shot on the 2nd of December, while the change in the other hare and in

the leveret was entire, except indeed a shading of grey on the back, which

is never purely white but in the depth of the severest winters.] The only

difference was, that the whole coat of the former appeared less pure. This

is easily accounted for, as in winter the creature, though receiving a fresh

accession of hair, loses none of the old, which also becomes white; whereas

in spring it casts it all, like other animals. Thus, by a merciful

provision, its winter covering is doubly thick; while at the same time,

being the colour of snow, (with which our hills are generally whitened at

that time of year,) it can more easily elude its numerous foes. The same

remark applies to the ptarmigan.

During a mild winter, when the ground is free from snow,

the white hare invariably chooses the thickest patch of heather it can find,

as if aware of its conspicuous appearance; and to beat all the bushy tufts

on the side and at the foot of rocky hills, at such a time, affords the best

chance of a shot. The purity, or dinginess of its colour is a true criterion

of the severity or mildness of the season. If the winter is open, I have

always remarked that the back and lower part of the ears retain a shade of

the fawn-colour; if, on the contrary, there is much frost and snow, the

whole fur of the hare is very bright and silvery, with scarcely a tint of

brown. When started from its form, I have constantly observed that it never

returns, evidently knowing that, its refuge has been discovered. It will

sometimes burrow in the snow, in order to scrape for food, and avoid the

cold wind, as well as for security. These burrows are not easily discovered

by an unaccustomed eye ; the hare runs round the place several times, which

completely puzzles an observer, and then makes a bound over, without leaving

any footmark to detect her retreat. It is hollowed out, like a mine, by the

hare's scraping and breath, and the herbage beneath nibbled bare.

When deer-stalking in Glenartney, last autumn, I was

quite amazed at the multitudes of Alpine hares. They kept starting up on all

sides, some as light-coloured as rabbits, and others so dark as to resemble

little moving pieces of granite. I could only account for their numbers from

the abundance of fine green food and the absence of sheep, which are as much

avoided by hares as by deer, from their dirting the ground with their tarry

fleeces. [Should anybody be disposed to call in question the correctness of

this word, I beg to say my title to it is long use and wont. "Tarry woo'!

tarry woo'!" Tarry woo is ill to spin."]

The alpine hare is a good deal less than the common -

shorter, and stouter made for its size - and its legs stronger, for climbing

in rocky places. Its colour in summer is a kind of fawn, and in winter the

tips of the ears, which are much shorter than those of the common species,

are jet black.