The golden-eagle is not nearly so

great a foe to the farmer as to the sportsman ; for although a pair, having

young ones, will occasionally pounce upon very young and unprotected lambs,

and continue their depredations until scared away, the more usual prey

consists of hares, rabbits, and grouse-a fact sufficiently proved by the

feathers and bones found in their eyries. A pair used to build every year in

Balquhidder, another in Glen-Ogle, and a third in Glenartney. The shepherds

seldom molested the old ones ; but by means of ladders, at considerable

risk, took the young and sold them. One of these brought to Callander, not

long ago, when scarcely full-fledged, would seize a live cat thrown to it

for food, and, bearing it away with the greatest ease, tear it to pieces,

the cat unable to offer any resistance, and

uttering the most horrid yells. From

the havoc they made among the game, especially when they had young, the

keepers in the neighbourhood have been very diligent of late years in

searching out the eyries, and trapping the old birds ; so that now, in this

part of Perthshire, there is not one for three nests that there were

formerly.

I recollect, some time ago, an eyrie

in Glen-Luss, where a pair hatched yearly; but since the female was shot, no

others have haunted the place. The shooting of this eagle was a service of

great danger, and the man who undertook it a most hardy and determined

fellow. The cliff was nearly perpendicular, and the only way of access was

over the top, where a single false step would have sent him headlong into

the gulf below. After creeping down a considerable way, he saw the eagle

sitting on her eggs, a long shot off; but his gun was loaded with swanshot,

so, taking a deliberate aim, he fired; she gave one shrill scream, extended

her wings, and died on her nest. His greatest difficulty now was, how to

avail himself of his success. He was not, however, the man to be balked :

so, at the most imminent risk, he managed to get to the eyrie, tumbled the

eagle over the cliff, and pocketed the two eggs. They were set under a hen

but did not hatch. Had they been left, the male would, probably, have

brought them out, as he has been often known to do in similar cases. I

afterwards broke one of the shells, and was quite astonished at its

thickness.

A fair shot may sometimes be got at

the male when there are young ones in the nest, as he will often swoop down

in their defence: at any other time, he is the most shy and wild of birds. I

only know of one instance to the contrary, and that was in the depth of a

very severe winter, when the creature was rendered desperate by hunger. The

gamekeeper of my late father was shooting wild-fowl, and having killed one,

sent his retriever to fetch it out of the water. The dog was in the act of

doing so, when an eagle stooped down, and seizing him, endeavoured to carry

off the duck: it was only by shouting with all his might that the keeper

could alarm the eagle so far as to make it fly a little clear of the dog,

when he shot it with his second barrel. The

scuffle took

place only twenty yards from where he stood, and he told me that he thought

the eagle would certainly have drowned his dog.

When two eagles are in pursuit of a

hare, they show great tact-it is exactly as if two well-matched greyhounds

were turning a hare-as one rises, the other descends, until poor puss is

tired out : when one of them succeeds in catching her, it fixes a claw in

her back, and holds by the ground with the other, striking all the time with

its beak. I have several times seen eagles coursed in the same way by

carrion-crows and ravens, whose territories they had invaded : the eagle

generally seems to have enough to do in keeping clear of his sable foes, and

every now and then gives a loud whistle or scream. If the eagle is at all

alarmed when in pursuit of his prey, he instantly bears it off alive. Where

alpine hares are plentiful, it is no unfrequent occurrence, when the

sportsman starts one, for an eagle to pounce down and carry it off,

struggling, with the greatest ease : in this case, he always allows the hare

to run a long way out of shot before he strikes, and is apt to miss

altogether. When no enemy is near, he generally adopts the more sure way of

tiring out his game.

The colour of the golden-eagle differs

very much: some are so dark as almost to justify the name of "the black

eagle," which they are often called in the Highlands-in others, the golden

tint is very bright; and many are of an even muddy-brown. I do not think

that the age of the bird has anything to do with this, as I have seen young

and old equally variable. The sure mark of a young one is the degree of

white on the tail: the first year the upper half is pure, which gradually

becomes less so by streaks of brown-about the third or fourth year no white

is to be seen.

THE SEA EAGLE.

I have not had an opportunity of

noticing the habits of the sea-eagle, never having been for any time in the

neighbourhood of its haunts. All my information regarding them is derived

from watching one or two tame ones which I met with in Ireland, where they

are more numerous than in Scotland, whose mountains are the grand resort of

the golden-eagle. The prey of both seems pretty much alike, except that the

sea-eagle is fonder of dead carcases, which may in part account for its

partiality to the sea-shore. Those I allude to devoured crows, jackdaws,

livers, fish, or almost any carrion that was thrown to them. Their eyries

are mostly in the precipitous cliffs on the coast.

The sea-eagle is rather larger than

the golden, and of a lighter brown. The bill, which is longer and broader,

but not so hooked as the other, is of a dull yellowish white. The whole of

the tail-feathers of the young ones are brown, when they gradually change to

white, which is complete about the fourth year-the very reverse of the

golden-eagle. The tail is also shorter, and the legs are not feathered to

the toes, like the other ; but quite enough to show that the bird was not

intended to subsist by fishing, like the osprey, whose legs are bare to the

thighs, which have only a thin covering of short feathers.

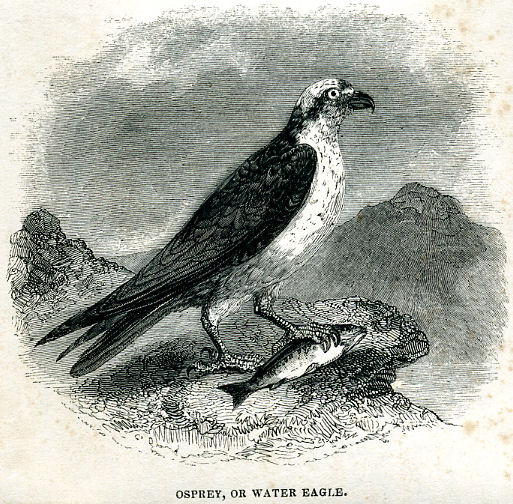

THE OSPREY

The osprey, or water-eagle, frequents

many of the Highland lochs ; a pair had their eyrie for many years on the

top of a ruin, in a small island on Loch Lomond. I am sorry to say I was the

means of their leaving that haunt, which they had occupied for generations.

It was their custom, when a boat

approached the island, to come out and meet it, always keeping at a most

respectful distance, flying round in very wide circles until the boat left

the place, when, having escorted it a considerable way, they would return

and settle on the ruin. Aware of their habit, I went, when a very young

sportsman, with a gamekeeper, and having concealed myself behind the stump

of an old tree, desired him to pull away the boat. The ospreys, after

following him the usual distance, returned, and gradually narrowing their

circles, the female, at last, came within fair distance-I fired, and shot

her. Not content with this, the gamekeeper and I ascended the ruin, and

finding nothing in the nest but a large seatrout, half-eaten, we set it in a

trap, and returning, after two or three hours, found the male caught by the

legs. They were a beautiful pair : the female, as in most birds of prey,

being considerably the largest-the woodcut is a most correct likeness. The

eggs of these ospreys had been regularly taken every year, and yet they

never forsook their eyrie. It was a beautiful sight to see them sail into

our bay on a calm summer night, and flying round it several times, swoop

down upon a good-sized pike, and bear it away as if it had been a minnow.

I have been told, but cannot vouch for

the truth of it, that they have another method of taking their prey in warm

weather, when fish bask near the shore. They fix one claw in a weed or bush,

and strike the other into the fish ; but I never saw them attempt any other

mode of " leistering " than that I have mentioned : when they see a fish,

they immediately settle in the air-lower their flight, and settle again-then

strike down like a dart. They always seize prey with their claws, the outer

toes of which turn round a considerable way, which gives them a larger and

firmer grasp. Owls have also this power, to enable them with greater

certainty to secure their almost equally agile victims; while the fern-owl

has the toe turned round like a parrot, to assist it in the difficult task

of catching insects in the air. But if this were the case with the others,

although it might be an advantage in the first instance, it would very

considerably weaken their hold when prey was struck.

I remember seeing another pair of

ospreys on Loch Menteith, that had their eyrie on the gnarled branch of an

old tree. They became so accustomed to the man who lets boats there, that

the female never even left her nest when he landed on the island, unless a

stranger was with him. Once, when he returned home after a short absence, he

saw one of them sitting on the tree, making a kind of wailing cry:

suspecting all was not right, he rowed to the island, and found the female

was missing, and the nest harried. They have never hatched there since : the

male has been frequently seen, but he has never found another mate. When

they had young, they did not confine their depredations to Loch Menteith,

but used to go, in quest of prey, to the other lochs in the neighbourhood ;

and, in the evening, would fly down the glen, carrying a fish a foot long in

their claws.

The nest of the osprey is lined with

coarse waterplants and grasses: the outside fenced with thick boughs, some

of them four inches round, and three feet and a-half long: proof enough of

the strength of its legs and wings. The eggs are as large as a hen's, with

reddish-brown spots. The osprey is about the size of the herring-gull ; the

breast nearly white, spotted with brown; back and wings dull brown ; the

thighs very muscular ; legs and claws, which are of bluish flesh colour,

equally so.