|

On the Peculiarities and Instinct of different Animals — Eggs of Birds —

Nests — Feeding habits — The beaks of Birds — Wings of Owl — Instinct in

finding Food — Ravens — Knowledge of Change of Weather — Fish.

THERE are two birds, which,

although wild and unapproachable at every other time, throw themselves

during the breeding-season on the mercy and protection of man : these are

the wood-pigeon and the missel-thrush. Scarcely any bird is more wary than

the wood-pigeon at other times, yet in the spring there are generally

half-a-dozen nests in the most exposed places close to my house, while the

old birds sit tamely, and apparently devoid of all fear, close to the

windows; they seem to have an instinctive knowledge of places where they

are allowed to go through the business of incubation without being

molested. In like manner, the missel-thrush, though during the rest of the

year it is nearly impossible to get within a hundred yards of it, forms

its nest in the apple-trees close to the house : they build at a height of

six or seven feet, in the fork of the tree where the main limbs branch

off; and although their nest is large, it is so carefully constructed of

materials resembling in colour the bark of the tree, and is made to blend

itself so gradually with the branches, as to show no distinct outline of a

nest, and to render it very difficult to discover; and this bird, at other

times so shy and timid, sits so close on her eggs that she will almost

allow herself to be taken by the hand. The missel-thrushes on the approach

of a hawk give a loud cry of alarm, and then collecting all their

neighbours, lead them on to attack the common enemy, swooping and striking

fearlessly at him, till he is driven out of the vicinity of their nests.

The observation of the different plans that birds adopt to avoid the

discovery and destruction of their eggs, is by no means an uninteresting

study to the naturalist. There is far more of art and cunning design in

their manner of building than the casual observer would suppose, and this,

even amongst the commonest of our native birds. The wren, for instance,

always adapts her nest to the colour and appearance of the surrounding

foliage, or whatever else may be near the large and comfortable abode

which she forms for her tiny family. In a beech-hedge near the house, in

which the leaves of the last year still remain at the time when the birds

commence building, the wrens form the outside of their nests entirely of

the withered leaves of the beech, so that, large as it is, the passer by

would never take it for anything more than a chance collection of leaves

heaped together, and though the nest is as firm and strong as possible,

they manage to give it the look of a confused mass of leaves, instead of a

round and compact ball, which it really is. The wren also builds near the

ground, about the lower branches of shrubs which are overgrown and

surrounded with long grass : in these situations she forms her nest of the

long withered grass itself, and twines and arches it over her roof in a

manner which would deceive the eyes of any animal, excepting those of

boys. When her nest is built, as it often is, in a spruce fir-tree, she

covers the outside with green moss, which of all the substances she could

select is the one most resembling the foliage of the spruce : the interior

of the wren's nest is a perfect mass of feathers and soft substances.

The chaffinch builds

usually in the apple-trees, whose lichen-covered branches she imitates

closely, by covering her nest with the lichens and moss of a similar

colour. Even her eggs are much of the same hue. Sometimes this bird builds

in the wall-fruit trees, when she collects substances of exactly the same

colour as the wall itself.

The greenfinch, building

amongst the green foliage of trees, covers her nest with green moss, while

her eggs resemble in colour the lining on which they are laid. The

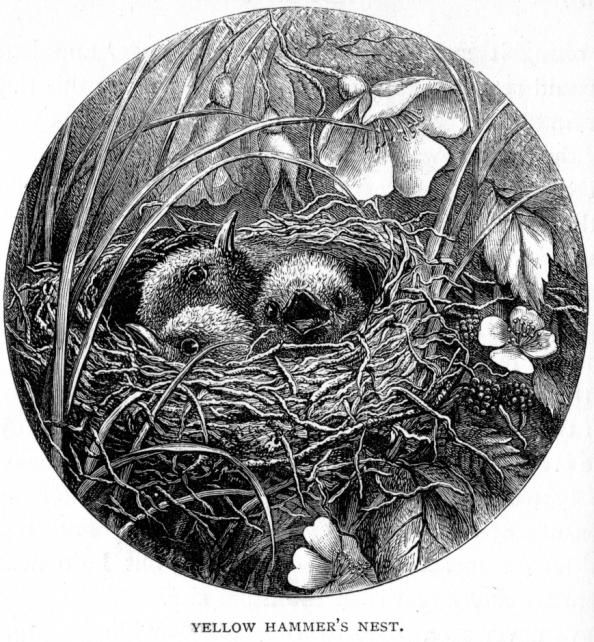

yellow-hammer, again, builds on or near the ground, and forming her nest

outwardly of dried grass and fibres, like those by which it is surrounded,

lines it with horsehair; her eggs too are not unlike in colour to her

nest—while the greenish brown of the bird herself closely resembles the

colour of the grass and twigs about her.

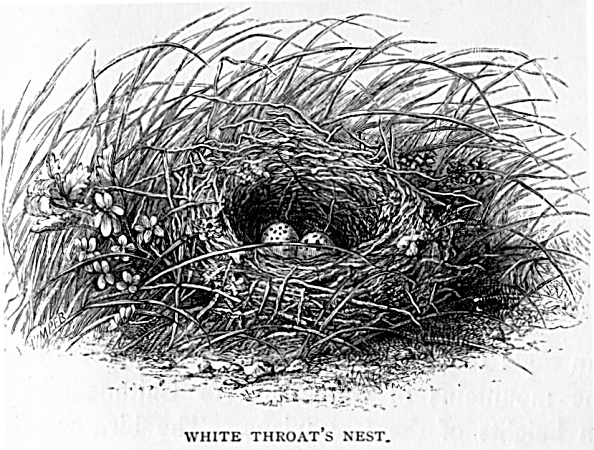

The little whitethroat

builds her nest on the ground, at the root of a tree or in long withered

grass, and carefully arches it over with the surrounding herbage, and to

hide -her little white eggs, places a leaf in front of the entrance

whenever she leaves her nest. When the partridge quits her eggs for the

purpose of feeding, she covers them in the most careful manner, and even

closes up her run by which she goes to and fro through the surrounding

grass. The same plan is adopted by the wild duck, who hides her eggs and

nest by covering them with dead leaves, sticks, and other substances,

which she afterwards smooths carefully over so as entirely to conceal all

traces of her dwelling. There are several domesticated wild ducks who

build their nests about the flower-beds and lawn near the windows—a

privilege they have usurped rather against the will of my gardener. Tame

as these birds are, it is almost impossible to catch them in the act of

going to or from their nests. They take every precaution to escape

observation, and will wait for a long time rather than go to their nests

if people are about the place.

The peewits, who lay their

eggs on the open fields with scarcely any nest, always manage to choose a

spot where loose stones or other substances of the same colour as their

eggs are scattered about. The terns lay their eggs in the same manner

amongst the shingle and gravel. So do the ring-dottrel, the

oyster-catcher, and several other birds of the same description; all of

them selecting spots where the gravel resembles their eggs in size and

colour. Without these precautions, the gray crows and other egg-eating

birds would leave but few to be hatched.

The larger birds, the size

of whose nests does not admit of their concealment, generally take some

precautions to add to their safety. A raven, who builds in a tree,

invariably fixes on the one that is most difficult to climb. She takes up

her abode in one whose large size and smooth trunk, devoid of branches,

set at defiance the utmost efforts of the most expert climbers of the

village school. When she builds on a cliff, she fixes on a niche protected

by some projection of the rock from all attacks both from above and below,

at the same time choosing the most inaccessible part of the precipice. The

falcon and eagle do the same. The magpie seems to depend more on the

fortification of brambles and thorns with which she surrounds her nest

than to the situation which she fixes upon. There is one kind of swallow

which breeds very frequently about the caves and rocks on the sea-shore

here. It is almost impossible to distinguish the nest of this bird, owing

to her choosing some inequality of the rock to hide the outline of her

building, which is composed of mud and clay of exactly the same colour as

the rock itself.

In fine, though some birds

build a more simple and exposed nest than others, there are very few who

do not take some precaution for its safety, or whose eggs and young do not

resemble in colour the substances by which they are surrounded. The are of

the common rabbit, in concealing and smoothing over the entrance of the

hole where her young are deposited, is very remarkable, and doubtless

saves them from the attacks of almost all their enemies, with the

exception of the wily fox, whose fine scent enables him to discover their

exact situation, and who in digging them out, instead of following the

hole in his excavations, discovers the exact spot under which they are,

and then digs down directly on them, thus saving himself a great deal of

labour.

The fox chooses the most

unlikely places and holes to produce her young cubs in; generally in some

deep and inaccessible earth, where no digging can get at them, owing to

the intervention of rocks or roots of trees. I once, however, two years

ago, found three young foxes about two days old, laid in a comfortable

nest in some long heather, instead of the usual subterraneous situation

which the old one generally makes choice of. Deer and roe fix upon the

most lonely parts of the mountain or forest for the habitation of their

fawns, before they have strength to follow their parents. I one day, some

time ago, was watching a red-deer hind with my glass, whose proceedings I

did not understand, till I saw that she was engaged in licking a

newly-born calf. I walked up to the place, and as soon as the old deer saw

me she gave her young one a slight tap with her hoof. The little creature

immediately laid itself down; and when I came up I found it lying with its

head flat on the ground, its ears closely laid back, and with all the

attempts at concealment that one sees in animals which have passed an

apprenticeship to danger of some years, whereas it had evidently not known

the world for more than an hour, being unable to run or escape. I lifted

up the little creature, being half inclined to carry it home in order to

rear it. The mother stood at the distance of two hundred yards, stamping

with her foot, exactly as a sheep would have done in a similar situation.

I, however, remembering the distance I had to carry it, and fearing that

it might get hurt on the way, laid it, down again and went on my way, to

the great delight of its mother, who almost immediately trotted up, and

examined her progeny carefully all over, appearing, like most other wild

animals, to be confident that her young and helpless offspring would be a

safeguard to herself against the attacks of her otherwise worst enemy. I

have seen roe throw themselves in the way of danger, in order to take my

attention from their young. No animal is more inclined to do battle for

her young ones than the otter; and I have known an instance of an old

female otter following a man who was carrying off her young for a

considerable distance, almost disputing the way with him, leaving the

water, and blowing at him in their peculiar manner; till at last, having

no stick or other means of defence, he actually got so frightened at her

threats that he laid down the two young ones and went his way. He returned

presently with a stick he had found, but both old and young had

disappeared. Even a partridge will do battle for her young. A hen

partridge one day surprised me by rushing out of some cover (through which

I was passing by a narrow path) and flying at a large dog who accompanied

me; she actually spurred and pecked him, driving him several yards along

the road; and this done, she ran at my heels like a barn-door hen. As I

passed, I saw her newly-hatched brood along the edge of the path. I have

known a pheasant do exactly the same thing. Wild ducks, snipes, woodcocks,

and many other shy birds, will also throw themselves boldly within the

reach of destruction in defence of their young.

|