|

Poaching in the Highlands — Donald — Poachers and Keepers — Bivouac in

Snow — Connivance of Shepherds — Deer killed — Catching a Keeper —

Poaching in the Forests — Shooting Deer by Moonlight — Ancient Poachers.

I HAD a visit last week

from a Highland poacher of some notoriety in his way. He is the possessor

of a brace of the finest deerhounds in Scotland, and he came down from his

mountain-home to show them to me, as I wanted some for a friend. The man

himself is an old acquaintance of mine, as I had fallen in with him more

than once in the course of my rambles. A finer specimen of the genus Homo

than Ronald I never saw. As he passes through the streets of a

country-town, the men give him plenty of walking-room; while not a girl

in the street but stops to look after him, and says to her companions —

"Eh, but yon's a bonnie lad." And indeed Ronald is a "bonnie lad" — about

twenty-six years of age—his height more than six feet, and with limbs

somewhat between those of a Hercules and an Apollo—he steps along the

street with the good-natured, self-satisfied swagger of a man who knows

all the women are admiring him. He is dressed in a plain grey kilt and

jacket, with an otter-skin purse and a low skull-cap with a long peak,

from below which his quick eye seems to take at a glance in everything

which is passing around him. A man whose life is spent much in hunting and

pursuit of wild animals acquires unconsciously a peculiar restless and

quick expression of eye, appearing to be always in search of something.

When Ronald doffs his cap, and shows his handsome hair and short curling

beard, which covers all the lower part of his face, and which he seems to

be something of a dandy about, I do not know a finer-looking fellow

amongst all my acquaintance—and his occupation, which affords him constant

exercise without hard labour, gives him a degree of strength and activity

seldom equalled. As he walked into my room, followed by his two

magnificent dogs, he would have made a subject worthy of Landseer in his

best moments—and it would have been a picture which many a fair damsel of

high, as well as low, degree, would have looked upon with pleasure.

Excepting when excited, he is the most quiet, good-natured fellow in the

world; but I have heard some stories of his exploits, in defence of his

liberty, when assailed by keepers, which proved his immense strength,

though he has always used it most good-naturedly. One feat of his is worth

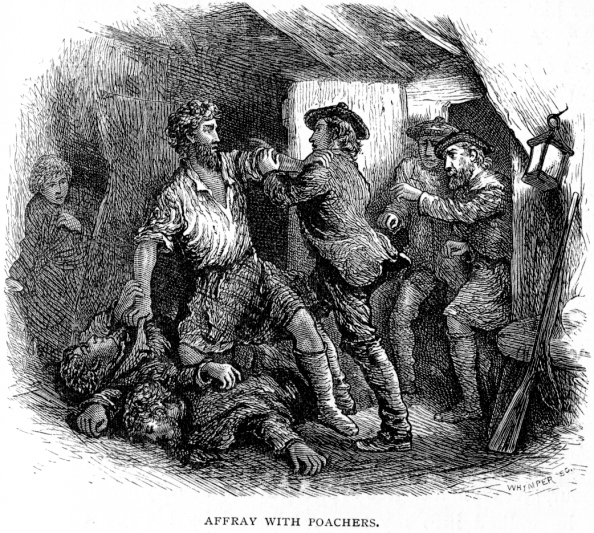

repeating. He was surprised by five men in a shealing, where he had

retired to rest after some days' shooting in a remote part of the

Highlands. Ronald had a young lad with him, who could only look on, in

consequence of having injured one of his hands.

Ronald was awoke from his sleep in the wooden

recess of the shealing (which is called a bed), by the five men coming

in,—and saying that they had tracked him there, that he was caught at

last, and must come along with them. "'Deed, lads," said Ronald, without

rising, "but I have had a long travel to-day, and if I am to go, you must

just carry me." "Sit quiet, Sandy," he added to his young companion.

"They'll no fash us, I'm thinking." The men, rather surprised at such cool

language from only one man with nobody to assist him but a boy, repeated

their order for him to get up and go with them; but receiving no

satisfactory answer, two of them went to his bed to pull him out " So I

just pit them under me" (said Ronald, in describing it), "and kept them

down with one knee. A third chiel then came up, with a bit painted wand,

and told me that he was a constable, but I could na help laughing at the

man, he looked so frightened like;—and I said to him, 'John Cameron, my

man, you'd be better employed making shoes at home, than coming here to

disturb a quiet lad like me, who only wants to rest himself:' and then I

said to the rest of them, still keeping the twa chiels under my knee, 'Ye

are all wrong, lads;' I'm no doing anything against the law; I am just

resting myself here, and rest myself I will : and you have no right to

come here to disturb me; so you'd best just mak off at once.' They had not

caught me shooting, Sir," he added, "and I was sure that no justice would

allow of their seizing me like an outlaw. Besides which, I had the licence

with me, though I didn't want to have to show it to them, as I was a

stranger there, and I didn't wish them to know my name. Weel, we went on

in this way, till at last the laird's keeper, who I knew well enough,

though he didn't know me, whispered to the rest, and all three made a push

at me, while the chiels below me tried to get up too. The keeper was the

only one with any pluck amongst them, and he sprang on my neck, and as he

was a clever like lad, I began to get sore pressed. Just then, however, I

lifted up my left hand, and pulled one of the sticks that served for

rafters, out of the roof above me, and my blood was getting quite mad

like, and the Lord only knows what would have happened if they hadn't all

been a bit frightened at seeing me get the stick, and when part of the

roof came falling on them, and so they all left me and went to the other

end of the shealing. The keeper was but ill pleased though—as for the bit

constable body, his painted stick came into my hand somehow, and he never

got it again ! One of the lads below my knee got hurt in this scuffle too,

indeed one of his ribs was broken, so I helped to lift him up, and put him

on the bed. The others threatened me a great deal, but did na like the

looks of the bit constable's staff I had in my hand. At last, when they

found that they could do nothing, they begged me, in the Lord's name, to

leave the shealing and gang my way in peace. But I did na like this, as it

was six hours at least to the next bothy where I could get a good rest, so

I just told them to go themselves—and as they did na seem in a hurry to do

so, I went at them with my staff, but they did na bide my coming, and were

all tumbling out of the door in a heap, before I was near them : I could

na help laughing to see them. It was coming on a wild night, and the poor

fellow in the bed seemed vera bad, so I called to them and told them they

might just come back and sleep in the shealing if they would leave me in

peace—and after a little talk they all came in, and I laid down in my

plaid at one end of the bothy, leaving them the other. I made the lad who

was with me watch part of the night to see they didn't get at me when I

was asleep, though I didn't want him to join in helping me, as they knew

his name, and it might have got him into trouble. In the morning I made my

breakfast with some meal I had with me, and gave them the lave of it. They

would have been right pleased to have got me with them,—but as they could

na do it, like wise chiels, they didn't try—so I wished them a good day,

and took the road. I had my gun and four brace of grouse, which they

looked at very hard indeed, but I did not let them lay hands on anything.

When I had just got a few hundred yards away, I missed my shot belt, so I

went back and found that the keeper had it, and would not give it up.

'You'll be giving me my property, lad, I'm thinking,' I said to him; but

he was just mad like with rage, and said that he would not let me have it.

However, I took him by the coat and shook him a bit, and he soon gave it

me, but he could na keep his hands off, and as I turned away, he struck me

a sair blow with a stick on my back; so I turned to him, and 'deed I was

near beating him weel, but after all I thocht that the poor lad was only

doing his duty, so I only gave him a lift into the burn, taking care not

to hurt him; but he got a grand ducking—and, Lord ! how he did swear. I

was thinking, as I travelled over the hills that day, it was lucky that

these twa dogs were not with me, for there would have been wild work in

the shealing. Bran there canna bide a scuffle but what he must join in it,

and the other dog would go to help him; and the Lord pity the man they

took hold of—he would be in a bad way before I could get this one off his

throat —wouldn't he, poor dog ?"—and Bran looked up in Ronald's face with

such a half lear, half snake-like expression, that I thought to myself

that I would about as soon encounter a tiger as such a dog, if his blood

was well roused. The

life of a Highland poacher is a far different one from that of an

Englishman following the same profession. Instead of a sneaking

night-walking ruffian, a mixture of cowardice and ferocity, as most

English poachers are, and ready to commit any crime that he hopes to

perpetrate with impunity, the Highlander is a bold fearless fellow,

shooting openly by daylight, taking his sport in the same manner as the

Laird, or the Sassenach who rents the ground. He never snares or wires

game, but depends on his dog and gun. Hardy and active as the deer of the

mountain, in company with two or three comrades of the same stamp as

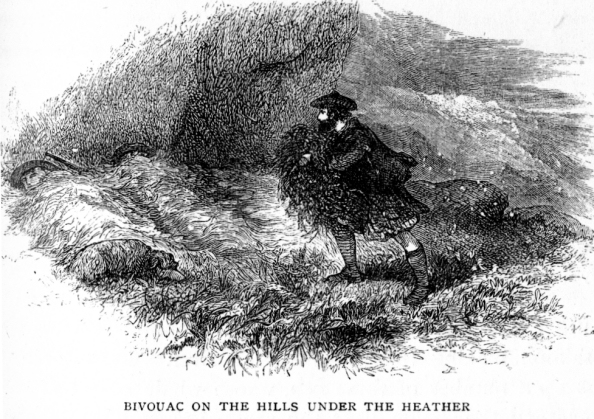

himself, he sleeps in the heather wrapped in his plaid, regardless of

frost or snow, and commences his work at daybreak. When a party of them

sleep out on the hill side, their manner of arranging their couch is as

follows:—If snow is on the ground, they first scrape it off a small space;

they then all collect a quantity of the driest heather they can find. The

next step is for all the party excepting one to lie down close to each

other, with room between one couple for the remaining man to get into the

rank when his duty is done, which is to lay all the plaids on the top of

his companions, and on the plaids a quantity of long heather; when he has

sufficiently thatched them in, he creeps into the vacant place, and they

are made up for the night. The coldest frost has no effect on them when

bivouacking in this manner. Their guns are laid dry between them, and

their dogs share their masters' couch.

With the earliest grouse-crow they rise and

commence operations. Their breakfast consists of meal and water. They

generally take a small bag of meal with them; but it is seldom that there

is not some good-natured shepherd living near their day's beat, who,

notwithstanding that he receives pay for keeping off or informing against

all poachers, is ready to give them milk and anything else his bothy

affords. If the shepherd has a peculiarly tender conscience, he vacates

the hut himself on seeing them approach, leaving his wife to provide for

the guests. He then, if accused of harbouring and assisting poachers, can

say in excuse, "'Deed, your honour, what could a puir woman do against

four or five wild Hieland lads with guns in their hands?" In fact, the

shepherds have a natural fellowing-feeling with the poachers, and, both

from policy and inclination, give them any assistance they want, or leave

their wives and children to do so; and many a side of red deer or bag of

grouse they get for this breach of promise to their masters. In the winter

season a poacher calls on the shepherd, and says, "Sandy, lad, if you look

up the glen there, you'll see a small cairn of stones newly put up; just

travel twenty paces east from that, and you'll find a bit venison to

yoursel'"—some unlucky deer having fallen to the gun of one of the

poaching fraternity. This sort of argument, as well as the fear of

"getting a bad name," is too strong for the honesty of most of the

shepherds, who are erroneously supposed to watch the game, and to keep off

trespassers. The keepers themselves, in the Highlands, as long as the

poachers do not interfere too much with their master's sport, so as to

make it imperative on them to interfere, are rather anxious to avoid a

collision with these "Hieland lads." For, although they never ill-use the

keepers in the savage manner that English poachers so frequently do, I

have known instances of keepers, who (although they were too smart

gentlemen to carry their master's game) have been taken prisoners by

poachers on the hill, and obliged to accompany them over their master's

ground, and carry the game killed on it all day. They have then either

been sent home, or, if troublesome, the poachers have tied them hand and

foot, and left them on some marked spot of the muir, sending a boy or

shepherd to release them some hours afterwards. Going in large bodies on

well-preserved ground, these men defy the keepers, and shoot in spite of

them. If pursued by a party stronger than themselves, they halt

occasionally, and fire bullets either over the heads of their pursuers or

into the ground near them, of course taking care not to hurt them. The

keepers go home, protesting that they have been fired upon and nearly

killed, while the Highlanders pursue their sport. The grand object of the

poachers being to keep out of the fangs of the law, they never uselessly

run the risk of being identified, and although they frequently have

licences, they always avoid showing them if possible, in order that their

names may not be known. If they shoot on ground where the watchers know

them, they take great care to avoid being seen. If they think there is any

likelihood of a prosecution occurring, they betake themselves to a

different part of the country till the storm is blown over. In some of the

wide mountain districts, a band of poachers can shoot the whole season

without being caught, and I fancy that many of the keepers, and even their

masters, rather wish to shut their eyes to the trespassing of these gangs

as long as they keep to certain districts and do not interfere with those

parts of the grouse-ground which are the most carefully preserved.

Some proprietors or lessees of

shooting-grounds make a kind of half compromise with the poachers, by

allowing them to kill grouse as long as they do not touch the deer;

others, who are grouse-shooters, let them kill the der to save their

birds. I have known an instance where a prosecution was stopped by the

aggrieved party being quietly made to understand, that if it was carried

on, "a score of lads from the hills would shoot over his ground for the

rest of the season."

In the eastern part of the Highlands and on the hills adjoining the

Highland roads, the grand harvest of the poachers arises from grouse,

which are shipped by the steamers, and sent by the coaches southwards, in

numbers that are almost incredible. Before the 12th of August, hundreds of

grouse are shipped to be ready in London on the first day that they become

legal food for her Majesty's subjects. In these districts the poachers

kill the deer only for their amusement, or to repay the obliging blindness

and silence of shepherds and others. Many a fine stag is either shot or

killed by dogs during the winter season;—the proprietor, or person who

rents the forest, supposing that his paying half a dozen watchers and

foresters ensures the safety of his deer.

"Indeed, his lordship has seven foresters,"

said a Highlander to me; "but they are mostly old men, and not that fit

for catching the likes of me; besides which, if we leave the forest quiet

during the time his lordship's down, they are not that over hard on us;

nor are we sair on their deer either, for they are all ceevil enough,

except the head forester, who is an Englishman, and we wouldna wish to get

them to lose their bread by being turned away on our account. So it's not

often we trouble the forest, unless, maybe, we have a young dog to try,

and we canna get a run at a deer on the marches of the ground, where it

would harm no one."

"And how do you manage not to be caught ?" was my question.

"Why, we sleep at some shepherd's house or

shealing; and if there is not one convenient, we lay out somewhere on the

ground, going to our sleeping-place after nightfall; and so we are ready

to get at the deer by daylight; and maybe we have killed one and carried

him off before the foresters have found out that we are out."

It is not so easy, however, for the poachers

to kill deer undiscovered with dogs as it is with the gun; for in the

event of the greyhounds getting in chase of a young stag or a hind, they

may be led away to a great distance, and in the course of the run move

half the deer in the forest; and there is no surer sign of mischief being

afloat than seeing the deer passing over the hills in a startled manner.

No man, accustomed to them, can mistake this sign of an enemy having

disturbed them; and one can judge pretty well the direction the alarm

comes from by taking notice of the quarter in which the wind is, and from

which part of the mountain the deer are moving. With a rifle, however, in

the hand of a good shot, the business is soon over, without frightening

the rest of the herd a tenth part so much, or making them change their

quarters to such a distance; and even if the shot is heard by the keepers,

which is a great chance, it is not easy to judge exactly from which

direction it comes amongst the numerous corries and glens which confuse

and mislead the listener.

Ronald told me that one day his dogs brought a

fine stag to bay in a burn close to the house of the forester on the

ground where he was poaching: "The forester, luckily, was no at hame, sir;

but the dogs made an awful noise, yowling at the stag; and a bit lassie

came out and tried to stone them off the beast; so I was feared they might

turn on her, and I just stepped down from where I was looking at them, and

putting my handkerchief over my face, that the lassie mightn't ken me,

took the dogs away, though it was a sair pity, as it was a fine beast; and

one of the dogs was quite young at the time, and it would have been a

grand chance for blooding him."

Many a deer is killed during the bright

moonlight nights. The poacher in this case finds out some grassy burn or

spot of ground where the deer are in the habit of feeding. Within shot of

this, and with his gun loaded with three pistol-balls, or a bullet and two

slugs, he lies ensconced, taking care to be well concealed before the time

that the deer come to feed, and keeping to leeward of the direction in

which they will probably arrive. Many an hour he may pass in his lonely

hiding-place, listening to every cry and sound of the different animals

that are abroad during the night-time, and peering out anxiously to see if

he can distinguish the object of his vigil approaching him. Perhaps,

although he may hear the deer belling or clashing their horns together in

the distance, none come within reach of his gun during the whole night;

and the call of the grouse-cock just before daybreak, as he collects his

family from their roosting-places in the heather, warns him that it is

time to leave his ambuscade, and betake himself home, chilled and

dispirited. It often however, happens that he hears the tramp of the deer

as they descend from the more barren heights to feed on the grass and

rushes near his place of concealment. On they come, till he can actually

hear their breathing as they crop the herbage; and can frequently

distinguish their ghostlike forms as they pass to and fro, sometimes

grazing, and sometimes butting at each other in fancied security. His own

heart beats so that he almost fears the deer will hear him. Often his

finger is on the trigger; but he still refrains, as no deer has come into

full view which he thinks worth killing. At last a movement amongst the

herd apprises him that the master stag is probably approaching. And

suddenly the gaunt form of the animal appears in strong relief between him

and the sky, standing on some rising bit of ground, within thirty yards of

the muzzle of his gun. The next instant the loud report is echoing and

rolling along the mountain side, till it. gradually dies away in the

distance. The stag, on receiving the shot, utters a single groan, partly

of affright and partly of pain, and drops to the ground, where he lies

plunging and floundering, but unable to rise from having received three

good-sized pistol-balls in his shoulder. The rest of the herd, frightened

by the report and the flash of the gun, dart off at first in all

directions; but soon collecting together, they can be heard in the still

night, for some time after they are lost to view, going up the hillside at

a steady gallop. The poacher rushes up to the stag, who is now nearly

motionless, only showing symptoms of life by his loud, deep breathing, and

an occasional quiver of his limbs, as his life is oozing rapidly away in

streams of blood. The skene dhu, plunged into the root of his neck, and

reaching to his heart, soon ends his struggles; and before the next

morning the carcass is carried off and cut up. Many a noble stag falls in

this way. Near the Caledonian Canal, which affords great facility of

carriage, the Lochaber poachers kill a considerable number during the

season, sending them to Edinburgh, Glasgow, or other large towns, where

they have some confidential friend to receive and sell them. In Edinburgh,

there are numbers of men who work as porters, etc., during the winter, and

poach in the Highlands during the autumn. When in town, these men are

useful to their friends on the hills in disposing of their game, which is

all killed for the purpose of being sent away, and not for consumption in

the country. Many

poachers of the class I have here described are of respectable origin, and

are well enough educated. When my aforesaid acquaintance Ronald called on

me, he had a neat kind of wallet with his dry hose, a pair of rather smart

worsted-worked slippers (he did not seem disposed to tell me what fair

hands had worked them), and clean linen, etc. He wore also a small French

gold watch, which had also been given him. Several of the Highlanders who

have lived in this way emigrate to Canada, and generally do well; others

get places as foresters and keepers, making the best and most faithful

servants. Their old allies seldom annoy them when they take to this

profession, as there is a great deal of good feeling amongst them, and a

sense of right, which prevents their thinking the worse of their quondam

comrade because he does his duty in his new line of life.

There is another class of hill poacher—the

old, half worn-out Highlander, who has lived and shot on the mountain

before the times of letting shooting-grounds and strict preserving had

come in. These old men, with their long single-barrelled gun, kill many a

deer and grouse, though not in a wholesale manner, hunting more from

ancient habit and for their own use than for the market. I have met some

quaint old fellows of this description, who make up by cunning and

knowledge of the ground for want of strength and activity. I made

acquaintance with an old soldier, who after some years' service had

returned to his native mountains, and to his former habits of poaching and

wandering about in search of deer. He lived in the midst of plenty of them

too, in a far off and very lonely part of Scotland, where the keepers of

the property seldom came. When they did so, I believe they frequently took

the old man out with them to assist in killing a stag for their master. At

other times he wandered through the mountains with a single-barrelled gun,

killing what deer he wanted for his own use, but never selling them. I

never in my life saw a better shot with a ball : I have seen him

constantly kill grouse and plovers on the ground. His occupation, I fear,

is at last gone, owing to changes in the ownership and the letting of the

shooting, for the last time I heard of him he was leading an honest life

as cattle-keeper.

When this man killed a deer far from home, he used to go to the nearest

shepherd's shealing, catch the horse, which- was sure to be found feeding

near at hand, and make use of it to carry home the deer. This done, he

turned the horse's head home; and let it loose, and as all Highland ponies

have the bump of locality strongly developed, it was sure to find its way

home. I have known one of these old poachers coolly ride his pony up the

mountain from which he intended to take a deer, turn it loose, and proceed

on his excursion. The pony, as cunning and accustomed to the work as his

master, would graze quietly near the spot where he was left, till his

services were required to take home the booty at night. The old man never

went to the hill till he had made sure of the whereabouts of the forester,

by which means he always escaped detection.

The principal object of pursuit of the

Highland poacher, next to grouse and deer, are ptarmigan, as these birds

always bring a high price, and by making choice of good weather and

knowing where to find the birds, a man can generally make up a bag that

repays him for his day's labour, as well as for his powder and shot. Being

sportsmen by nature, as well as poachers, they enjoy the wild variety of a

day's ptarmigan-shooting as much as the more legal shooter does. In

winter, when a fresh fall of snow has taken place, a good load of white

hares is easily obtained, as this animal is found in very great numbers on

some mountains, since the destruction of vermin on so large a scale has

taken place. What with the sale of these different kinds of game, and a

tolerable sum made by breaking dogs, a number of young men in the

Highlands make a very good income during the shooting-season, which

enables them to live in idleness the rest of the year, and often affords

them the means of emigrating to America, where they settle quietly down

and become extensive and steady farmers.

|