|

Variety of Game.

The list of game killed by

my own gun on the 21st of October, appears in my game-book to have been as

follows:—

Grouse 6

Partridge 13

Woodcock 1

Pheasant 1

Wild Duck 1

Snipe 4

Teal 1

Curlew 3

Plover 4

Jacksnipe 2

Hare 5

Rabbit 2

Though the number of

animals in this list may not seem great to many of my sporting friends in

England and Scotland, a prettier variety of game could scarcely be killed

by one gun in any single locality, and the whole of them were shot during

a few hours' walk, and in a most stormy and windy day. I had promised to

send a hamper of game to a friend in Edinburgh, and knowing that he would

prize it more if I could make up a variety than if I sent him double the

quantity of any one kind, I determined to hunt a wild part of my

shooting-ground, where I should have a chance of finding ducks, snipes,

etc.

I started after breakfast

with a single pointer, and my everlasting companion, an old retriever. As

the steam-boat for Edinburgh started the next day, I was obliged, though

the wind blew nearly a hurricane, to make the best of it, and face the

wind in the dreary and upland ground, which I had determined to beat, and

where I had sent an attendant to meet me.

Passing over a long tract

of furze and broom, I killed a couple of hares, and drove some partridges

off down to windward; but as they flew quite out of the direction in which

I meant to shoot, I did not follow them. My pointer stood immediately on

getting into an extensive piece of grazing-ground; his head high up showed

me that the birds were at some distance. He drew on for some two or three

hundred yards, when two large covies of partridges rose, and, unable to

face the wind, drifted back over my head like leaves. Bang, bang — and a

brace of them fell dead sixty yards behind me, though shot when nearly

over my head, and killed at once. I marked down the rest, and got a brace

more, when they went straight away, as if determined to make their next

resting-place somewhere about Norway. But my line was to windward still,

in order to hunt some ground where there was a chance (though a bad one)

of a brace or so of grouse.

Picking up a snipe or two,

and a hare, I worked up hill against the wind along a tract of wild

heather and pasture-ground. In the midst of this was a small peat-bog,

and, when passing it, I flushed a brace of mallards, who, after drifting

about and trying to. make their way to the sea, turned and alighted in a

swampy piece of ground, where there were some small pools. By their manner

I was sure that they had some companions where they alighted, so desiring

the man who accompanied me to hold the pointer, I tried to stalk

unperceived to the spot where they were, allowing my old retriever (who

was well accustomed to duck-shooting) to accompany me. I had got to within

a hundred yards, when an old mallard, whom I had not seen, rose at my feet

out of a pool, and quacked an alarm that made six more rise out of shot of

me. I avenged myself, however, on him, bringing him down quite dead at a

considerable distance. Several pairs of ducks rose at the report, and all

went off to the sea.

I had scarcely commenced

hunting again with the pointer, when he stood at something close to his

nose, stopping dead short in the midst of his gallop. I walked up,

expecting a jack-snipe; when, out of a small hollow, or rather hole in the

heather, rose eight grouse. They flew wild, but I killed one with my first

barrel, and two with the second — the wind blowing them up into a heap

just as I pulled the trigger: the rest flew over a height not far up,

right in the eye of the wind. I knew the violence of the gale must stop

them; and accordingly I found them again, immediately over the ridge, and

killed a brace more, marking down the rest close to a cottage. My next two

barrels killed one only. The rest went off a long distance. The star of my

friend's larder was still in the ascendant, for before I turned to beat

homewards I killed two jacksnipes; thus making up four partridges, six

grouse, four snipes, three hares, and a wild duck. Not a bad bag already.

I beat on towards the coast, killing some partridges, a brace of rabbits,

a woodcock, and a hare or two.

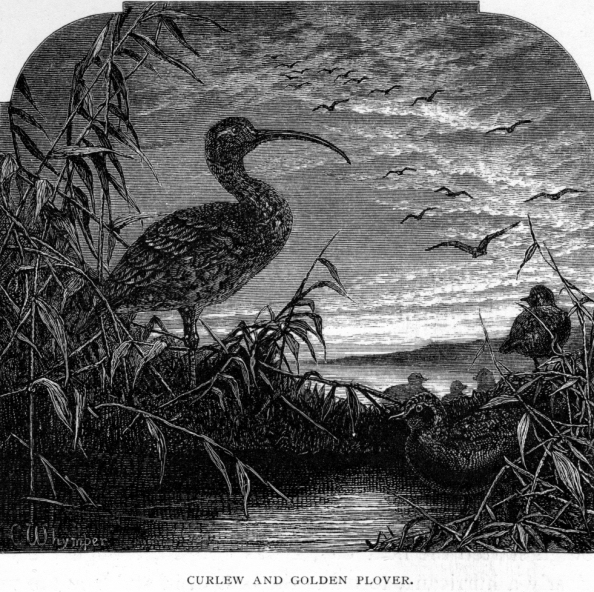

Near the shore I saw an

immense flock of curlews and other birds in a tolerably good situation for

getting near them. Of all shore-birds there is none, not even the wild

duck, so difficult of approach as a curlew. With the most acute sense of

hearing, their organs of smelling are so sensitive, that the moment you

get "betwixt the wind and their nobility" they take wing, giving the alarm

by their loud shrill whistle to every other bird within hearing. I got,

however, unperceived to within forty yards of them, and having loaded one

barrel with a cartridge, I fired right and left at the flock.

There was a rare confusion

and scuffling amongst them, and my retriever brought me, one by one, three

curlews and four golden plovers. Some other birds dropped here and there

out at sea, but I could only get the above number. A brace of teal rose at

the shot and alighted in a ditch in the adjoining field; so, loading

quickly, I walked to the place : as they rose rather wild, I only bagged

one, the other bird going away hard struck. I then followed the course of.

the rushy ditch, or rather rivulet, which led towards my house, having

already a fair quantity of game. My dog pointed, and I killed a snipe; I

did not reload the barrel, as I was near home, but hunted on along the

rushes, expecting another snipe to present my remaining charge to. The dog

presently stood, and then drew slowly on till he came very near to the end

of the rushes, when he pointed dead at something close to him. I walked

about the rushes, but could find nothing, till, just as I was giving it

up, a magnificent old cock pheasant, who had wandered away from the woods,

rose in a furrow of the field adjoining the rushes. He was rather far off,

but I killed him dead, making as pretty a climax or tail-piece to a day's

wild shooting as I could have wished; and though I have very often far

exceeded the number which I killed that day, I do not ever remember

bagging a handsomer collection of animals in so short a time. Every bird,

too, was in beautiful plumage and condition, and when laid out, ready to

be packed up, made quite a picture.

An account of a day's

shooting is rather a dry affair, but I have given it as showing the great

variety of game which is to be found in this part of the country. I had,

indeed, as good a chance of killing a roebuck as anything else, as I

passed through a piece of ground where I have repeatedly killed roe. I saw

an old blackcock too, but he was in a bare place, and rose out of shot.

Golden plovers and curlews

collect on the low grounds in immense flocks at this time of the year,

previous to settling down in their winter-quarters. Both these birds breed

generally in very high situations, and though wary in the winter, and

difficult to approach, yet during the summer, when crossing the mountains,

I have been absolutely annoyed by the continued clamour of curlews flying

and screaming within a few yards of my head, and following up their

persecutions for a considerable distance, when it would probably be taken

up by another pair with fresh lungs, whose breeding-place I might be

approaching.

The golden plover has a

plaintive and rather sweet note as he flits rapidly round the traveller

who intrudes on his domain. Indeed, in the spring, the note of the golden

plover, as he ascends with rapid wheelings high above your head, is quite

musical, and approaches nearly to the note of a thrush or blackbird. Not

only the whistle of the plover, but even the harsh cry of the landrail,

and the monotonous call of the cuckoo, are always grateful to my ear,

because, being heard only in the spring-time, they are associated in my

mind with the idea of the departure of winter and the return of fine

weather. It is often a matter of astonishment to me how the throat of a

bird so tender and delicately formed as the landrail can emit such hard

and grating cries, which sound more as if they were produced by some iron

or brazen instrument than from the windpipe of a bird. The raven or crow

look as if they ought to be the owners of a harsh and croaking voice, and

a shrill note comes appropriately from the throat of a barn-door cock ;

but a landrail appears to be a bird quite unfitted to produce a sound like

that of a piece of iron drawn along the teeth of a rusty saw. There is a

way of imitating their cry so exactly, as to bring the bird to your feet,

but I never could succeed in doing so, or indeed in making it answer me at

all, though I have tried the plan which I was told was infallible, of

drawing the edges of two horse's ribs against each other, one of them

being smooth and the other notched like a saw. Although the fields were

swarming with the birds at the time, I never succeeded in persuading even

a single one to answer me.

|