|

The Muckle Hart of Benmore.

Sunday. — This evening,

Malcolm, the shepherd of the shealing at the foot of Benmore, returning

from church, reported his having crossed in the hill a track of a hart of

extraordinary size; and he guessed it must be "the muckle stag of Benmore."

This was an animal seldom seen, but which had long been the talk and

marvel of the shepherds for its wonderful size and cunning. They love the

marvellous, and in their report "the muckle stag" bore charmed life; he

was unapproachable and invulnerable. I had heard of him too, and, having

got the necessary information resolved to try to break the charm, though

it should cost me a day or two.

Monday. — This morning at

sunrise, I with my rifle, Donald carrying my double-barrel, and Bran, took

our way up the glen to the shealing at the foot of Benmore. Donald had no

heart for this expedition. He is not addicted to superfluous conversation

but I heard him mutter something of a "feckless errand — as good deer

nearer hame." Bran had already been the victor in many a bloody tussle

with hart and fox. We held for the most part up the glen, but turning and

crossing to seek every likely corrie and burn on both sides. I shot a wild

cat, stealing home to its cairn in the early morning; and we several times

in the day came on deer, but they were hinds with their calves, and I was

bent on higher game. As night fell, we turned down to the shealing rather

disheartened; but the shepherd cheered me by assuring me the hart was

still in that district, and describing his track, which he said was like

that of a good-sized heifer. Our spirits were quite restored by a meal of

fresh-caught trout, oat-cake, and milk, with a modicum of whisky, which

certainly was of unusual flavour and potency.

Tuesday. — We were off

again by daybreak. I will pass by several minor adventures, but one cannot

be omitted. Malcolm went with us to show us where he had last seen the

track. As we crossed a long reach of black and broken ground, the first

ascent from the valley, two golden eagles rose out of a hollow at some

distance. Their flight was lazy and heavy, as if gorged with food, and on

examining the place we found the carcass of a sheep half eaten, one of

Malcolm's flock. He vowed vengeance; and, merely pointing out to us our

route, returned for a spade to dig a place of hiding near enough the

carcass to enable him to have a shot at the eagles if they should return.

We held on our way, and the greater part of the day without any luck to

cheer us, my resolution "not to be beat" being, however, a good deal

strengthened by the occasional grumbling of Donald. Towards the afternoon,

when we had tired ourselves with looking with our glasses at every corrie

in that side of the hill, at length, in crossing a bare and boggy piece of

ground, Donald suddenly stopped, with a Gaelic exclamation, and pointed —

and there, to be sure, was a full, fresh footprint, the largest mark of a

deer either of us had ever seen. There was no more grumbling. Both of us

were instantly as much on the alert as when we started on our adventure.

We traced the track as long as the ground would allow. Where we lost it,

it seemed to point down the little burn, which soon lost itself to our

view in a gorge of bare rocks. We proceeded now very cautiously, and

taking up our station on a concealed ledge of one of the rocks, began to

search the valley below with our telescopes. It was a large flat, strewed

with huge slabs of stone, and surrounded on all sides but one with dark

rocks. At the farther end were two black lochs, connected by a sluggish

stream; beside the larger loch a bit of coarse grass and rushes, where we

could distinguish a brood of wild ducks swimming in and out. It was

difficult ground to see a deer in, if lying; and I had almost given up

seeking, when Donald's glass became motionless, and he gave a sort of

grunt as he changed his posture, but without taking the glass from his

eye. "Ugh ! I'm thinking yon's him, sir : I'm seeing his horns." I was at

first incredulous. What he showed me close to the long grass I have

mentioned looked for all the world like some withered sticks; but the

doubt was short. While we gazed the stag rose and commenced feeding; and

at last I saw the great hart of Benmore! He was a long way off, perhaps a

mile and a half, but in excellent ground for getting at him. Our plan was

soon arranged. I was to stalk him with the rifle, while Donald, with my

gun and Bran, was to get round, out of sight, to the pass by which the

deer was likely to leave the valley. My task was apparently very easy.

After getting down behind the rock I had scarcely to stoop my head, but to

walk up within shot, so favourable was the ground and the wind. I walked

cautiously, however, and slowly, to give Donald time to reach the pass. I

was now within three hundred yards of him, when, as I leant against a slab

of stone, all hid below my eyes, I saw him give a sudden start, stop

feeding, and look round suspiciously. What a noble beast! what a stretch

of antler! with a mane like a lion ! He stood for a minute or two,

snuffing every breath. I could not guess the cause of his alarm; it was

not myself; the light wind blew fair down from him upon me; and I knew

Donald would give him no inkling of his whereabouts. He presently began to

move, and came at a slow trot directly towards me. My pulse beat high.

Another hundred yards forward and he is mine ! But it was not so to be. He

took the top of a steep bank which commanded my position, saw me in an

instant, and was off, at the speed of twenty miles an hour, to a pass wide

from that where Donald was hid. While clattering up the hill, scattering

the loose stones behind him, two other stags joined him, who had evidently

been put up by Donald, and had given the alarm to my quarry. It was then

that his great size was conspicuous. I could see with my glass they were

full-grown stags, and with good heads, but they looked like fallow-deer as

they followed him up the crag. I sat down, disappointed for a moment, and

Donald soon joined me, much crestfallen, and cursing the stag in a curious

variety of Gaelic oaths. Still it was something to have seen "the muckle

stag," and nil desperandum was my motto. We had a long and weary walk to

Malcolm's shealing; and I was glad to get to my heather bed, after

arranging that I should occupy the hiding-place Malcolm had prepared near

the dead sheep next morning.

Wednesday. — We were up an

hour before daylight; and in a very dark morning I sallied out with

Malcolm to take my station for a shot at the eagles. Many a stumble and

slip I made during our walk, but at last I was left alone fairly ensconced

in the hiding-place, which gave me hardly room to stand, sit, or lie. My

position was not very comfortable, and the air was nipping cold just

before the break of day. It was still scarcely grey dawn when a bird, with

a slow, flapping flight, passed the opening of my hut, and

lighted out of sight, but near, for I heard him strike the ground; and my

heart beat faster. What was my disappointment when his low crowing croak

announced the raven! and presently he came in sight, hopping and walking

suspiciously round the sheep; till, supposing the coast clear, and little

wotting of the double-barrel, he hopped upon the carcass, and began with

his square cut and thrust beak to dig at the meat. Another raven soon

joined him, and then two more ; who, after a kind of parley, quite

intelligible, though in an unknown tongue, were admitted to their share of

the banquet. I was watching their voracious meal with some interest, when

suddenly they set up a croak of alarm, stopped feeding, and all turned

their knowing-looking eyes in one direction. At that moment I heard a

sharp scream, but very distant. The black party heard it too; and

instantly darted off, alighting again at a little distance. Next moment a

rushing noise, and a large body passed close to me; and the monarch of the

clouds lighted at once on the sheep, with his broad breast not fifteen

yards from me. He quietly folded up his wings; and, throwing back his

magnificent head, looked round at the ravens, as if wondering at their

impudence in approaching his breakfast-table. They kept a respectful

silence, and hopped a little farther off. The royal bird then turned his

head in my direction, attracted by the alteration in the appearance of the

ground which he had just noticed in the dim morning light. His bright eye

that instant caught mine as it glanced along the barrel. He rose ; as he

did so I drew the trigger, and he fell quite dead half-a-dozen yards from

the sheep. I followed Malcolm's directions, who had predicted that one

eagle would be followed by a second, and remained quiet, in hopes that his

mate was not within hearing of my shot. The morning was brightening, and I

had not waited many minutes when I saw the other eagle skimming low over

the brow of the hill towards me. She did not alight at once. Her eye

caught the change in the ground or the dead body of her mate, and she

wheeled up into the air. I thought her lost to me, when presently I heard

her wings brush close over my head; and then she went wheeling round and

round above the dead bird, and turning her head downwards to make out what

had happened. At times she stooped so low that I could see the sparkle of

her eye and hear her low complaining cry. I watched the time when she

turned up her wing towards me, and fired, and dropped her actually on the

body of the other. I now rushed out. The last bird immediately rose to her

feet, and stood gazing at me with a reproachful, half-threatening look.

She would have done battle, but death was busy with her; and, as I was

loading in haste, she reeled and fell perfectly dead. Eager as I had been

to do the deed, I could not look on the royal birds without a pang. But

such regrets were now too late. Passing over the shepherd's rejoicings,

and my incredible breakfast, I must return to our great adventure. Our

line of march to-day was over ground so high that we came repeatedly into

the midst of ptarmigan. On the very summit Bran had a rencontre with an

old mountain fox, toothless, yet very fat, whom he made to bite the dust.

We struck at one place the tracks of the three deer, but of the animals

themselves we saw nothing. We kept exploring corrie after corrie till

night fell; and as it was in vain to think of returning to the shealing,

which yet was the nearest roof, we were content to find a sort of niche in

the rock, tolerably screened from all winds; and having almost filled it

with long heather, flower upwards, we wrapped our plaids round us, and

slept pretty comfortably.

Thursday. — A dip in the

burn below our bivouac renovated me. I did not observe that Donald

followed my example in that; but he joined me in a hearty attack on the

viands which still remained in our bag; and we started with renewed

courage. About mid-day we came on a shealing beside a long narrow loch,

fringed with beautiful weeping-birches, and there we found means to cook

some grouse which I had shot to supply our exhausted larder. The shepherd,

who had "no Sassenach," cheered us by his report of "the deer " being

lately seen, and describing his usual haunts. Donald was plainly getting

disgusted and home-sick. For myself, I looked upon it as my fate that I

must have that hart; so on we trudged. Repeatedly, that afternoon, we came

on the fresh tracks of our chase, but still he remained invisible. As it

got dark, the weather suddenly changed, and I was glad enough to let

Donald seek for the bearings of a "whisky bothie" which he had heard of at

our last stopping-place. While he was seeking for it the rain began to

fall heavily, and through the darkness we were just able to distinguish a

dark object, which turned out to be a horse. "The lads with the still will

no be far off," said Donald. And so it turned out. But the rain had

increased the darkness so much, that we should have searched in vain if I

had not distinguished at intervals, between the pelting of the rain and

the heavy rushing of a black burn that ran beside us, what appeared to me

to be the shrill treble of a fiddle. I could scarcely believe my ears. But

when I communicated the intelligence to Donald, whose ears were less

acute, he jumped with joy. " It's all right enough, sir; just follow the

sound; it's that drunken deevil, Sandy Ross; ye'll never haud a fiddle

frae him, nor him frae a whisky-still." It was clear the sound came from

across the black stream, and it looked formidable in the dark. However,

there was no remedy. So grasping each the other's collar, and holding our

guns high over head, we dashed in, and staggered through in safety, though

the water was up to my waist, running like a mill-race, and the bottom was

of round slippery stones. Scrambling up the bank, and following the merry

sound, we came to what seemed a mere hole in the bank, from which it

proceeded. The hole was partially closed by a door woven of heather; and,

looking through it, we saw a sight worthy of Teniers. On a barrel in the

midst of the apartment — half hut, half cavern — stood aloft, fiddling

with all his might, the identical Sandy Ross, while round him danced three

unkempt savages; and another figure was stooping, employed over a fire in

the corner, where the whisky-pot was in full operation. The fire, and a

sliver or two of lighted bog-fir, gave light enough to see the whole, for

the place was not above ten feet square. We made our approaches with

becoming caution, and were, it is needless to say, hospitably received;

for who ever heard of Highland smugglers refusing a welcome to sportsmen ?

We got rest, food, and fire — all that we required — and something more •

for long after I had betaken me to the dry heather in the corner, I had

disturbed visions of strange orgies in the bothy, and of my sober Donald

exhibiting curious antics on the top of a tub. These might have been the

productions of a disturbed brain; but there is no doubt that when daylight

awoke me, the smugglers and Donald were all quiet and asleep, far past my

efforts to rouse them, with the exception of one who was still able to

tend the fire under the large black pot.

Friday. — From the state in

which my trusty companion was, with his head in a heap of ashes, I saw it

would serve no purpose to awake him, even if I were able to do so. It was

quite clear that he could be good for nothing all day. I therefore secured

some breakfast and provisions for the day (part of them oatcake which I

baked for myself), tied up Bran to wait Donald's restoration, and departed

with my rifle alone. The morning was bright and beautiful, the

mountain-streams overflowing with last night's rain. I was now thrown on

my own resources, and my own knowledge of the country, which, to say the

truth, was far from minute or exact. "Benna-skiach" was my object to-day,

and the corries which lay beyond it, where at this season the large harts

were said to resort. My way at first was dreary enough, over a long slope

of boggy ground, enlivened, however, by a few traces of deer having

crossed, though none of my "chase." I at length passed the slope, and soon

topped the ridge, and was repaid for my labour by a view so beautiful,

that I sat down to gaze at it, though anxious to get forward. Looking down

into the valley before me, the foreground was a confusion of rocks of most

fantastic shape, shelving rapidly to the edge of a small blue lake, the

opposite shore of which was a beach of white pebbles, and beyond, a

stretch of the greenest pasture, dotted with drooping white-stemmed

birches. This little level was hemmed in on all sides by mountains, ridge

above ridge, the lowest closely covered with purple heath, the next more

green and broken by ravines, and the highest ending in sharp serrated

peaks tipped with snow. Nothing moved within range of my vision, and

nothing was to be seen that bespoke life but a solitary heron standing on

one leg in the shallow water at the upper end of the lake. From hence I

took in a good range, but could see no deer. While I lay above the lake,

the day suddenly changed, and heavy wreaths of mist came down the

mountain-sides in rapid succession. They reached me soon, and I was

enclosed in an atmosphere through which I could not see twenty yards. It

was very cold too, and I was obliged to move, though scarcely well knowing

whither. I followed the course of the lake, and afterwards of the stream

which flowed from it, for some time. Now and then a grouse would rise

close to me, and, flying a few yards, light again on a hillock, crowing

and croaking at the intruder. The heron, in the darkness, came flapping

his great wings close past me; I almost fancied I could feel the movement

they caused in the air. Nothing could be done in such weather, and I was

not sure that I might not be going away from my object. It was getting

late too, and I made up my mind that my most prudent plan was to arrange a

bivouac before it became quite dark. My wallet was empty, except a few

crumbs, the remains of my morning's baking. It was necessary to provide

food : and just as the necessity occurred to me, I heard, through the

mist, the call of a cock grouse as he lighted close to me. I contrived to

get his head between me and the sky as he was strutting and croaking on a

hillock close at hand; and aiming at where his body ought to be, I fired

my rifle. On going up to the place, I found I had not only killed him, but

also his mate, whom I had not seen. It was a commencement of good luck.

Sitting down, I speedily skinned my birds, and took them down to the burn

to wash them before cooking. In crossing a sandy spot beside the burn, I

came upon — could I believe my eyes? — "the Track." Like Robinson Crusoe

in the same circumstances, I started back; but was speedily at work taking

my information. There were prints enough to show the hart had crossed at a

walk leisurely. It must have been lately for it was since the burn had

returned to it's natural size, after the last night's flood. But nothing

could be done till morning, so I set about my cooking ; and having after

some time succeeded in lighting a fire, while my grouse were slowly

broiling, I pulled a quantity of heather, which I spread in a corner a

little protected by an overhanging rock : I spread my plaid upon it, and

over the plaid built another layer of heather. My supper ended, which was

not epicurean, I crawled into my nest under my plaid, and was soon sound

asleep. I cannot say that my slumbers were unbroken. I dreamt of the great

stag thundering up the hills with preternatural speed, and of noises like

cannon (which I have since learnt to attribute to their true cause — the

splitting of fragments of rock under a sudden change from wet to sharp

frost), and above all, the constant recurrence of visions of weary

struggles through fields of snow and ice kept me restless, and at length

awoke me to the consciousness of a brilliant skylight and keen frost — a

change that rejoiced me in spite of the cold.

Saturday. — Need I say my

first object was to go down and examine the track anew. There was no

mistake. It was impossible to doubt that "the muckle hart of Benmore " had

actually walked through that burn a few hours before me, and in the same

direction. I followed the track, and breasted the opposite hill. Looking

round from its summit, it appeared to me a familiar scene, and on

considering a moment, I found I overlooked from a different quarter the

very same rocky plain and the two black lochs where I had seen my chase

three days before. I had not gazed many minutes when I saw a deer lying on

a black hillock which was quite open. I lay down immediately, and with my

glass made out at once the object of all my wanderings. My joy was

somewhat abated by his position, which was not easily approachable. My

first object, however, was to withdraw myself out of his sight, which I

did by crawling backwards down a little bank till only the tops of his

horns were visible, and they served to show me that he continued still. As

he lay looking towards me, he commanded with his eye three-fourths of the

circle, and the other quarter, where one might have got in upon him under

cover of the little hillock, was unsafe from the wind blowing in that

direction. A burn ran between him and me, one turn of which seemed to come

within two hundred yards of him. It was my only chance; so, retreating

about half-a-mile, I got into the burn in hidden ground, and then crept up

its channel with such caution that I never allowed myself a sight of more

than the tips of his horns, till I had reached the nearest bend to him.

There, looking through a tuft of rushes, I had a perfect view of the noble

animal, lying on the open hillock, lazily stretched out at length, and

only moving now and then to scratch his flank with his horn. I watched him

for fully an hour, the water up to my knees all the time. At length he

stirred, gathered his legs together, and rose; and arching his back, he

stretched himself just as a bullock does when rising from his night's

lair. My heart throbbed, as turning all round he seemed to try the wind

for his security, and then walked straight to the burn, at a point about

one hundred and fifty yards from me. I was much tempted, but had

resolution to reserve my fire, reflecting that I had but one barrel. He

went into the burn at a deep pool, and standing in it up to his knees,

took a long drink. I stooped to put on a new copper cap and prick the

nipple of my rifle; and — on looking up again, he was gone ! I was in

despair; and was on the point of moving rashly, when I saw his horns again

appear a little farther off, but not more than fifty yards from the burn.

By and by they lowered, and I judged he was lying down. "You are mine at

last," I said; and I crept cautiously up the bed of the burn till I was

opposite where he had lain down. I carefully and inch by inch placed my

rifle over the bank, and then ventured to look along it. I could see only

his horns, but within an easy shot. I was afraid to move higher up the bed

of the burn, where I could have seen his body; the direction of the wind

made that dangerous. I took breath for a moment and screwed up my nerves;

and then with my cocked rifle at my shoulder and my finger on the trigger,

I kicked a stone which splashed into the water. He started up instantly;

but exposed only his front towards me. Still he was very near, scarcely

fifty yards, and I fired at his throat just where it joins the head. He

dropped on his knees to my shot; but was up again in a moment and went

staggering up the hill. Oh, for one hour of Bran; Although he kept on at a

mad pace, I saw he was becoming too weak for the hill. He swerved and

turned back to the burn and came headlong down within ten yards of me,

tumbling into it apparently dead. Feeling confident, from the place where

my ball had taken effect, that he was dead, I threw down my rifle, and

went up to him with my hunting-knife. I found him stretched out, and as I

thought dying and I laid hold of his horns to raise his head to bleed him.

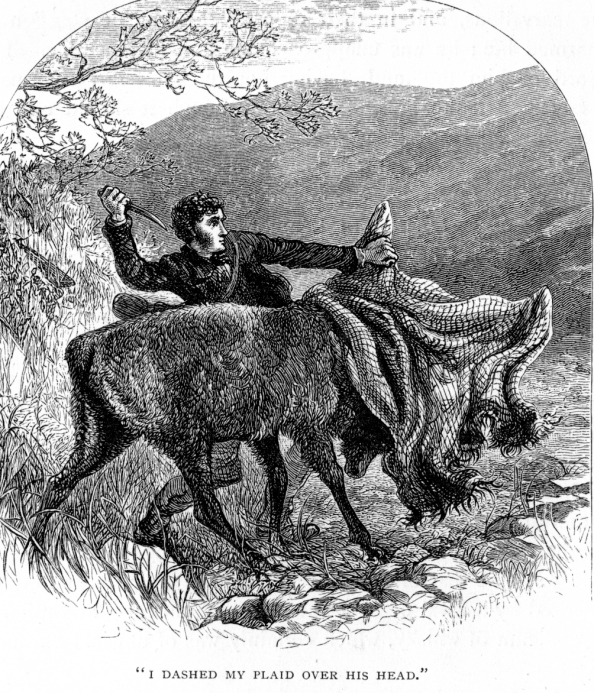

I had scarcely touched him when he sprang up, flinging me backwards on the

stones. It was an awkward position. I was stunned by the violent fall;

behind me was a steep bank of seven or eight feet high ; before me the

bleeding stag with his horns levelled at me, and cutting me off from my

rifle. In desperation I moved; when he instantly charged, but fortunately

tumbled ere he quite reached me. He drew back again like a ram about to

but, and then stood still with his head lowered, and his eyes bloody and

swelled, glaring upon me. His mane and all his coat were dripping with

water and blood; and as he now and then tossed his head with an angry

snort, he looked like some savage beast of prey. We stood mutually at bay

for some time, till, recovering myself, I jumped out of the burn so

suddenly, that he had not time to run at me, and from the bank above, I

dashed my plaid over his head and eyes, and threw myself upon him. I

cannot account for my folly, and it had nearly cost me dear. The poor

beast struggled desperately, and his remaining strength foiled me in every

attempt to stab him in front; and he at length made off, tumbling me down,

but carrying with him a stab in the leg which lamed him. I ran and picked

up my rifle, and then kept him in view as he rushed down the burn on three

legs towards the loch. He took the water and stood at bay up to his chest

in it. As soon as he halted, I commenced loading my rifle, when to my

dismay I found that all the balls I had remaining were for my

double-barrel, and were a size too large for my rifle. I sat down and

commenced scraping one to the right size, an operation that seemed

interminable. At last I succeeded; and, having loaded, the poor stag

remaining perfectly still, I went up within twenty yards of him, and shot

him through the head. He turned over and floated, perfectly dead. I waded

in and towed him ashore, and then had leisure to look at my wounds and

bruises, which were not serious, except my shin-bone, which was scraped

from ankle to knee by his horn. I soon had cleaned my quarry and stowed

him away as safely as I could, and then turned down the glen at a gay

pace. I found Donald with Bran reposing at Malcolm's shealing; and for all

reproaches on his misconduct, I was satisfied with sending him to bring

home the "muckle hart of Benmore," a duty which he performed before

night-fall.

|