|

The Water-Ouzel: Nest; Singular Habits; Food; Song of Kingfisher: Rare

Visits of; Manner of Fishing Terns: Quickness in Fishing; Nests of.

For several years a pair of those singular little birds the water-ouzel

have built their nest and reared their young on a buttress of a bridge,

across what is called the Black burn, near Dalvey.

This year I am sorry to see, that owing to

some repairs in the bridge, the birds have not returned to their former

abode. The nest, when looked at from above, had exactly the appearance of

a confused heap of rubbish, drifted by some flood to the place where it

was built, and attached to the bridge just where the buttress joins the

perpendicular part of the masonry. The old birds evidently took some

trouble to deceive the eye of those who passed along the bridge, by giving

the nest the look of a chance collection of material.

I do not know, among our common birds, so

amusing and interesting a little fellow as the water-ouzel, whether seen

during the time of incubation, or during the winter months, when he

generally betakes himself to some burn near the sea, less likely to be

frozen over than those more inland. In the burn near this place there are

certain stones, each of which is always occupied by one particular

water-ouzel; there he sits all day, with his snow-white breast turned

towards you, jerking his apology for a tail, and occasionally darting off

for a hundred yards or so, with a quick, rapid, but straight-forward

flight; then down he plumps into the water, remains under for perhaps a

minute or two; and then flies back to his usual station. At other times

the water-ouzel walks deliberately off his stone down into the water, and,

despite of Mr. Waterton's strong opinion of the impossibility of the feat,

he walks and runs about on the gravel at the bottom of the water,

scratching with his feet among the small stones, and picking away at all

the small insects and animalculae; which he can dislodge. On two or three

occasions I have witnessed this act of the water-ouzel, and have most

distinctly seen the bird walking and feeding in this manner under the

pellucid waters of a Highland burn. It is in this way that the water-ouzel

is supposed to commit great havoc in the spawning beds of salmon and

trout, uncovering the ova, and leaving what it does not eat open to the

attacks of eels and other fish, or liable to be washed away by the

current; and, notwithstanding my regard for this little bird, I am afraid

I must admit that he is guilty of no small destruction amongst the spawn.

The water-ouzel has another very peculiar

habit which I have never heard mentioned. In the coldest days of winter I

have seen him alight on a quiet pool, and with out-stretched wings recline

for a few moments on the water, uttering a most sweet; and merry song

then rising into the air, he wheels round and round for a minute or two,

repeating his song as he flies back to some accustomed stone. His notes

are so pleasing, that he fully deserves a place in the list of our

song-birds; though I never found but one other person, besides myself, who

would own to having heard the water-ouzel sing. In the early spring, too,

he courts his mate with the same harmony, and pursues her from bank to

bank, singing as loudly as he can; often have I stopped to listen to him

as he flew to and fro along the burn, apparently full of business and

importance then pitching on a stone, he would look at me with such

confidence, that, notwithstanding the bad name he has acquired with the

fishermen, I never could make up my mind to shoot him. He frequents the

rocky burns far up the mountains, building in the crevices of the rocks,

and rearing his young in peace and security, amidst the most wild and

magnificent scenery.

The nest is large, and built, like a wren's,

with a roof; the eggs are a transparent white. The people here have an

idea that the water-ouzel preys on small fish, but this is an erroneous

idea; the bird is not adapted in any way either for catching fish or for

swallowing them.

During a severe frost last year, I watched for

some time a common kingfisher, who, by some strange chance, and quite

against its usual habits, had strayed into this northern latitude. He

first caught my eye while darting like a living emerald along the course

of a small unfrozen stream between my house and the river; he then

suddenly alighted on a post, and remained a short time motionless in the

peculiar strange attitude of his kind, as if intent on gazing at the sky.

All at once a new idea comes into his head, and he follows the course of

the ditch, hovering here and there like a hawk, at the height of a yard or

so above the water; suddenly down he drops into it, disappears for a

moment, and then rises into the air with a trout of about two inches long

in his bill; this he carries quickly to the post where he had been resting

before, and having beat it in an angry and vehement manner against the

wood for a minute, he swallows it whole. I tried to get at him, coveting

the bright blue feathers on his back, which are extremely useful in

fly-dressing, but before I was within shot, he darted away, crossed the

river, and sitting on a rail on the opposite side, seemed to wait as if

expecting me to wade after him ; this, however, I did not think it worth

while doing, as the water was full of floating ice, so I left the

kingfisher where he was, and never saw him again. Their visits to this

country are very rare ; I only have seen one other, and he was sitting on

the bow of my boat watching the water below him for a passing trout small

enough to be swallowed.

The kingfisher, the terns, and the solan geese

are the only birds that fish in this way, hovering like a hawk in the air

and dropping into the water to catch any passing fish that their sharp

eyesight can detect. The rapidity with which a bird must move to catch a

fish in this manner is one of the most extraordinary things that I know. A

tern, for instance, is flying at about twenty yards high suddenly he

sees some small fish (generally a sand-eel, one of the most active little

animals in the world),down drops the bird, and before the slippery little

fish (that glances about in the water like a silver arrow) can get out of

reach, he is caught in the bill of the tern, and in a moment afterwards is

either swallowed whole, or journeying rapidly through quite a new element

to feed the young of his captor. Often in the summer have I watched flocks

of terns fishing in this manner at a short distance from the shore, and

never did I see one emerge after his plunge into the water without a

sand-eel. When I have shot at the bird as he flew away with his prey, I

have picked up the sand-eel, and there are always the marks of his bill in

one place, just behind the head, where it seems to be invariably caught.

The terns which breed in the islands on a loch

in the woods of Altyre, fully five miles in a straight line from where

they fish, fly up to their young with every sand-eel they catch. I have

seen them fly backwards and forwards in this way for hours together,

apparently bringing the whole of their food from the sea, notwithstanding

the distance; their light body and long swallow-like wings make this long

flight to and fro less fatiguing to the tern than it would be to almost

any other bird.

Great numbers of terns breed every year on the

sandhills. Their eggs, three in number, are laid in a small hole scraped

amongst the shingle, or on the bare sand. Generally, however, they choose

a place abounding in small stones; and their eggs being very nearly of the

same colour as the pebbles, it is very difficult to distinguish them. The

nests being frequently at so considerable a distance from the water, it

has often been a matter of surprise to me how the young birds can live

till they have strength to journey to the sea-shore. I never yet could

find any of the newly-hatched terns near the nests, and am of opinion that

the old birds in some way or other carry off their young, as soon as they

are out of the egg, to some place more congenial to so essentially a

water-bird than the arid ground on which they are hatched. During fine

weather the terns never sit on their eggs in the daytime, but, uttering

unceasing cries, hover and fly about over the spot where their nests are.

All day long have I seen them hovering in this manner, with a flight more

like that of a butterfly than of a bird. If a man approaches their eggs,

they dash about his head with a loud angry clamour; and all the other

terns who have eggs, for miles around, on hearing the cry of alarm, fly to

see what it is all about, and having satisfied their curiosity, return to

the neighbourhood of their own domicile, ready to attack any intruder. If

a crow in search of eggs happens to wander near the terns'

building-places, she is immediately attacked by the whole community, every

bird joining in the chase, and striking furiously at their common enemy,

who is glad to make off as quickly as she can. The terns, having pursued

her to some distance, return seemingly well satisfied with their feat of

arms. I have also detected the fox by the rapid swoops of the terns as

they dash at him if he happens to pass near their nests.

There is one kind of tern that breeds on the

sandhills, which is peculiarly beautiful, the lesser tern, or Terna minuta.

This little bird, scarcely bigger than a swift, and of a pale blue in the

upper part of her plumage, is of the most satin-like and dazzling

whiteness in all the lower portions. It is a most delicate-looking

creature, but has a stronger and more rapid flight than the larger kinds,

and when he joins in their clamorous attacks on any enemy, utters a louder

and shriller cry than one could expect to hear from so small a body. Its

eggs are similar in colour to those of the common tern, but much smaller.

The roseate tern also visits us. I do not know

that I have ever found the eggs of this kind, but I have distinguished the

bird by its pale bluish coloured breast, as it hovered over my head

amongst the other terns.

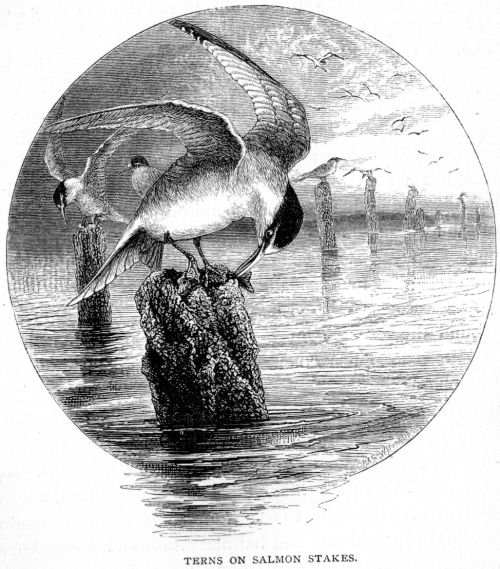

A favourite position of the tern is on the

stakes of the salmon-fishers' nets. Frequently every stake has a tern on

it, where, if unmolested, they sit quietly watching the operations of the

fishermen. Indeed, they are rather a tame and familiar bird, not much

afraid of man, and seeming to trust (and, as far as I am concerned, not in

vain) to their beauty and harmlessness as a safeguard against the

wandering sportsman. Excepting when wanting a specimen for any particular

purpose, I make a rule never to molest any bird that is of no use when

dead, and which, like the tern, is both an interesting and beautiful

object when living.

These birds make but a short sojourn with us,

arriving in April in great numbers, and collecting in flocks on the sands

of the bay for a few days. They then betake themselves to their

breeding-places, and, having reared their young, leave us before the

beginning of winter.

|