|

The Findhorn River — Excursion to Source — Deer-stalking — Shepherds —

Hind and Calf — Heavy rain — Floods — Walk to Lodge — Fine Morning —

Highland Sheep — Banks of River — Cottages.

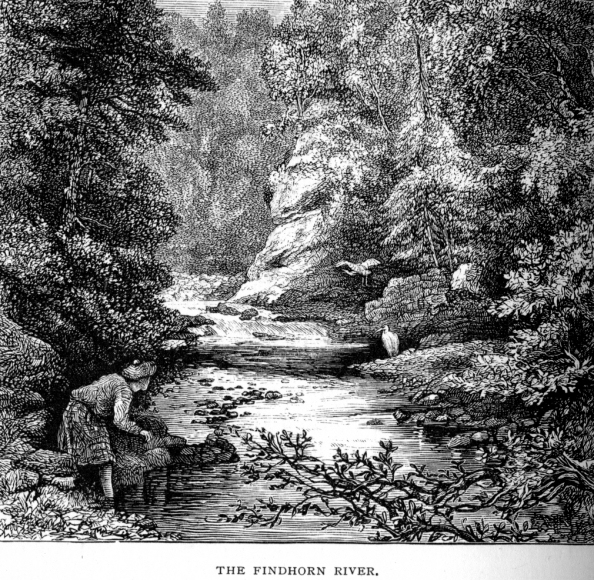

I do not know a stream that

more completely realises all one's ideas of the beauty of Highland scenery

than the Findhorn, taking it from the spot where it is no more than a

small rivulet, bubbling and sparkling along a narrow gorge in the far-off

recesses of the Monaghliahd mountains, down to the bay of Findhorn, where

its accumulated waters are poured into the Moray Firth. From source to

mouth, this river is full of beauty and interest. On a bright August day,

the 6th of the month, I joined a friend in a deer-stalking expedition,

near the source of the Findhorn, in the Monaghliahd. We went from near

Inverness to our quarters. For the greatest part of our way our road was

over a flat though elevated range of dreary moor, more interesting to the

eye of a grouse-shooter than to any one else. When within a few miles of

the end of our journey, the Findhorn came in sight, passing like a silver

stripe, edged with bright green, through the brown mountains, and

sparkling brightly in the evening sun. The sides of the hills immediately

overhanging the river are clothed with patches of weeping-birch and

juniper, with here and there a black hut perched on a green knoll, dotted

with groves of the rugged and ancient-looking birch-trees. About these

solitary abodes, too, were small patches of oats and potatoes. The mavis

with its joyous note, and the blackbird's occasional full and rich song,

greeted us as we passed through these wooded tracts. Sometimes a

wood-pigeon would crash through the branches close to us as we wound round

some corner of the wood.

Having arrived at our

destination, we made ourselves as comfortable as we could, and retired to

rest. In the morning we started in different directions. I, accompanied by

a shepherd, went westward towards the sources of the river. I cannot say

that I had much hope of finding deer, as the whole line of my march was

full of sheep; and red-deer will very seldom remain quiet when this is the

case, either from a dislike to the sheep themselves, or from knowing that

where there are sheep there are also shepherds and shepherds' dogs. With

black cattle, on the contrary, deer live in tolerable amity; and I have

frequently seen cattle and deer feeding together in the same glen.

I went some miles westward,

keeping up the course of the river, or rather parallel to it, sometimes

along its very edge, and at other times at some distance from the water.

The highest building on the river, if building it can be termed, is a

small shealing, or summer residence of the shepherds, called, I believe,

Dahlvaik. Seeing some smoke coming from this hut, we went to it. When at

some few hundred yards off, we were greeted with a most noisy salute from

some half-dozen sheep-dogs, who seemed bent on eating up my bloodhound.

But having tried her patience to the uttermost, till she rolled over two

or three of them rather roughly (not condescending, however, to use her

teeth), the colleys retreated to the door of the shealing, where they

redoubled, if possible, their noise, keeping up a concert of howling and

barking enough to startle every deer in the country. My companion, whose

knowledge of the English tongue was not very deep, told me that the owners

of the dogs would be some "lads from Strath Errick," who were to hold a

conference with him about some sheep.

A black-headed, unshaven

Highlander having come out, and kicked the dogs into some kind of quiet,

we entered the hut, and found two more "lads" in it, one stretched out on

a very rough bench, and the other busy stirring up some oatmeal and hot

water for their breakfast. The smoke for a few moments prevented my making

out what or who were in the place. I held a short (very short)

conversation with the three shepherds, they understanding not one word of

English, and I understanding very few of Gaelic. But, by the help of the

man who accompanied me, I found out that a stag or two were still in the

glen, besides a few hinds. The meal and water having been mixed

sufficiently, it was emptied out into a large earthen dish, and placed

smoking on the lid of a chest. Each man then produced from some recess of

his plaid a long wooden spoon; whilst my companion assisted in the

ceremony by fetching some water from the river in a bottle. They all

three, then, having doffed their bonnets, and raising their hands,

muttered over a long Gaelic grace. Then, without saying a word, set to

with good will at the scalding mess before them, each attacking the corner

of the dish nearest him, shovelling immense spoonfuls down their throats ;

and when more than usually scalded — their throats must have been as

fire-proof as that of the Fire King himself — taking a mouthful of the

water in the bottle, which was passed from one to the other for that

purpose. Having eaten a most extraordinary quantity of the pottage, each

man wiped his spoon on the sleeve of his coat, and again said a grace. The

small remainder was then mixed with more water and given to the dogs, who

had been patiently waiting for their share. After they had licked the dish

clean, it was put away into the meal-chest, the key of which was then

concealed in a hole of the turf wall. I divided most of my cigars with the

men to smoke in their pipes, and handed round my whisky-flask, reserving a

small modicum for my own use during the day.

From this place to its

source the river is very narrow, and confined between steep and rocky

hills that come down to the edge of the water; varied here and there by

less abrupt ascents, covered with spreading juniper-bushes and green

herbage. On one of these bright spots we saw a hind and her calf, the

former standing to watch us as we passed up the opposite side of the

river, while her young one was playing about her like a lamb. They did not

seem to care much for our coming there; and having watched us for some

time, and seeing that we had no evil intention towards them, the hind

recommenced feeding, only occasionally stopping to see that we did not

turn. The ring-ouzel, that near cousin of the blackbird, frequently

flitted across the glen, and, perching on a juniper-bush, saluted us with

its wild and sweet song.

The morning was bright, and

the river sparkled and danced over its stony bed; while every little pool

was dimpled by the rising of the trout, who jumped without dread of hook

and line at the small black gnats that were playing about the surface of

the water. A solitary heron was standing on a stone in the middle of the

stream, seemingly quite regardless of us. But while I was looking at his

shadowy figure, which was perfectly reflected in the water beneath him,

the bird suddenly flew off with a cry of alarm, occasioned by the

appearance of a peregrine falcon, who passed with even and rapid flight at

no great height along the course of the river, without taking the least

notice of the heron.

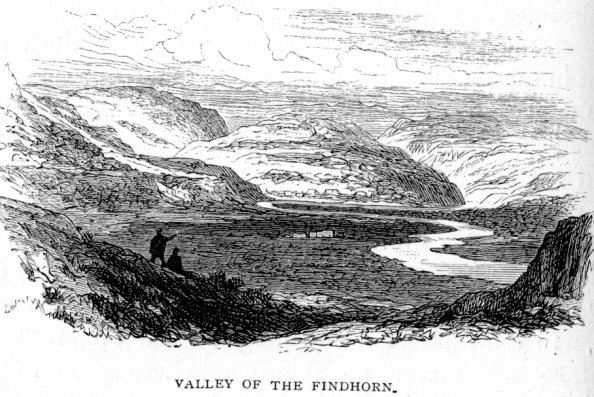

Beautiful in its grand and

wild solitude is the glen where the Findhorn takes its rise; seldom does

the foot of man pass by it. It is too remote even for the sportsman ; and

the grouse cock crows in peace, and struts without fear of pointer or gun,

when he comes down from the hill-slopes at noonday to sip the clear waters

of the springs that give birth to this beautiful river. The red-deer

fearlessly quenches his thirst in them, as he passes from the hills of

Killen to the pine-woods in Strathspey. Seldom is he annoyed by the

presence of mankind, unless a chance shepherd or poacher from Badenoch

happens to wander in that direction. Having rested for a short time, and

satisfied my curiosity respecting the source of the river, we struck off

over some very dreary slopes of high ground on the north-east,

interspersed with green stripes, through which small burns make their way

to swell the main stream of the river. Not a deer did we see, but great

quantities of grouse, who, when flushed, flew to short distances, and

alighting on some hillock, crowed as it were in defiance. A cold chill

that passed over me made me turn and look down the course of the stream,

and the first thing that I saw was a dense shower or cloud of rain working

its way up the valley, and gradually spreading over the face of the

country, shutting out hill after hill from our view as it crept towards

us. In the other direction all was blue and bright. "We must turn home, or

we shall never get across the streams and burns," was my ejaculation to

the shepherd. "'Deed, ay, Sir," was his answer; and, tightening our

plaids, we turned our faces towards the east. As the rain approached, the

ring-ouzel sang more loudly, as if to take leave of the sunshine; and the

grouse flew to the dry and bare heights, where they crowed incessantly.

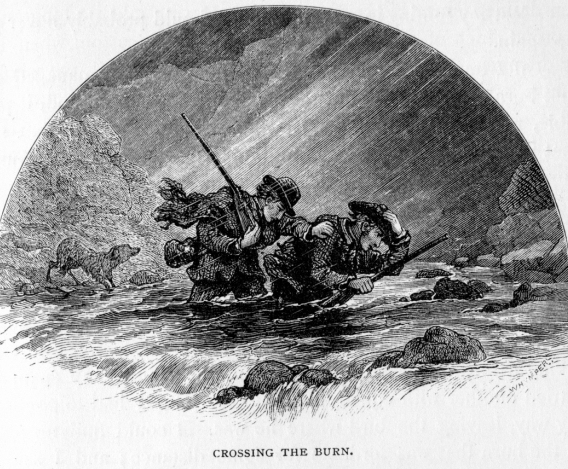

The rain gradually came on,

accompanied by a cold cutting wind. I never saw such rain in my life; it

was a perfect deluge; and in five minutes I was as wet as if I had been

swimming through the river. We saw the burns we had to cross in our way

home tumbling in foaming torrents down the hill-sides. In the morning we

had stepped across them without wetting our feet.

The first one that we came

to I looked at with wonder. Instead of a mere thread of crystal water,

creeping rather than flowing through the stones which filled its bed, we

had to wade through a roaring torrent, which was carrying in its course

pieces of turf, heather, and even large stones. We crossed with some

difficulty, holding by each other's collars. Two or three burns we passed

in this manner, the rain still continuing, and if possible increasing. I

looked round at my companion, and was only prevented from laughing at his

limp and rueful countenance by thinking that he probably had just as much

cause for merriment in my appearance. The poor hound was perfectly

miserable, as she followed me with the rain running in streams down her

long ears.

After some time we came

opposite the shealing where we had been with the shepherds in the morning.

And here my companion said that he must leave me, having particular

business with the other men, who had come on purpose to meet him there. He

warned me to be very careful in crossing the burns, as, if I once lost my

footing in any of them, I should probably never get up again.

Off I tramped through the

sodden ground. I managed the first burn pretty well. But the next one was

wider, and, if possible, more rapid. I had no stick to sound its depth,

but saw that it was too strong to venture into; so I turned up its course

hoping it would get narrower and shallower higher up. Its banks were steep

and rocky, and covered in some parts with hazel and birch. On a withered

branch of one of the latter was a large buzzard, sitting mournfully in the

rain, and uttering its shrill, wild cry, a kind of note between a whistle

and a scream. The bird sat so tamely, that in a pet I determined to try if

I could not stop his ominous-sounding voice with a rifle-ball. But, after

taking a most deliberate aim at him, the copper cap snapped. I tried

another with equally bad success. So I had to continue my way, leaving the

bird where he was. I could find no place in the burn that was fordable for

some distance; and I said to myself, "If I had but a stick to sound the

water with!" The next moment almost I saw one about six feet in length

standing upright in the ground. I could scarcely believe my eyes. The

stick must have been left by mere chance by some shepherd. It came most

opportunely for me, however. The first place I tried in the water with it

(a spot where I thought I could wade), it went in to the depth of at least

five feet. This would never do; so on I went up the hill, splashing

through the wet bog and heather. At last I came to a place in the burn,

where, by leaping from one stone to the other, at no small risk to myself,

I managed to get across. My poor hound had to swim, and was very nearly

carried off by the stream. Instead of turning down again towards the

river, I still kept the high ground, remembering that I had to pass

through two or three other burns, one of them, at least, much larger than

any I had already crossed. I had now to make my way over a long flat,

covered with coarse grass, and full of holes of water and rotten bog. I

never walked a more weary mile in my life, sinking, as I did, up to my

knees at nearly every step. When in the middle of this, I saw three hinds

and a calf walk deliberately along a ridge not three hundred yards from

me. I had to lead the hound for some distance, as she lost all her fatigue

on coming on their scent, which she did as we passed \ their track. I made

no attempt on them, knowing the useless state of my rifle. We kept on, and

at last got across all the burns excepting the largest, which was still

between me and my dry clothes and dinner. I had now got quite high up in

the barren hill, leaving everything but rock and heather far below me, the

birch-woods not extending above half-a-mile from the river. I came here to

another long flat piece of ground; and having to make many windings and

turnings to cross different small streams, I suddenly discovered that I

had entirely lost my points of the compass. So, sitting down, I tried to

make out which way the wind blew, as my only guide. This soon set me

right; and after another hour or two of weary walking, I found myself on

the hilltop almost immediately overhanging the Lodge, the smoke from whose

chimneys was a most welcome sight. On getting to it, I found the river

raging and pouring down through its narrow banks in a manner that no one

who has not seen a Highland river in full flood can imagine, carrying with

it every kind of debris that its course could produce.

At eleven o'clock at night,

when looking at it by the light of a brilliant northern moon (every cloud

having long disappeared), we found that the water had already begun to

subside, though it still roared on with great fury. On the opposite rocks

we could see many a mountain burn as they glanced in the moonlight. Every

bird and animal was at rest, excepting a couple of owls answering each

other with loud hootings, which were plainly heard above the noise of the

waters.

The friend I was with being

obliged to go home the next day, I determined also to wend my way to the

low country, and to follow the river till I reached my own house.

We started on horseback

very early. Nothing could exceed the beauty of the morning, and

everything, animate and inanimate, seemed to smile rejoicingly. The

Findhorn had returned to it usual size, and danced merrily in the

sunshine. The streams on the opposite cliffs were again like silver

threads, and the sheen were winding along the narrow paths on the face of

the rocks, the animals looking to us as if they were walking, like flies,

on the very face of the perpendicular cliffs. We saw a flock of some

thirty or so making their way in single file along these paths • while we

watched them they came to a place where their road was broken up by the

yesterday's torrents. We could not understand what they would do. The path

was evidently too narrow to turn ; and, as well as we could see with our

glasses, to proceed was impossible. However, after a short halt the leader

sprang over the obstacle, whatever it was, and alighted safely on the

opposite side. The least false step would have sent him down many hundred

feet. However, they all got over in safety, and having filed away for some

little distance slowly along the face of the precipice, they came to a

small green shelf, apparently only a few yards square, the object of all

their risk and labour. As fast as they got on this they dispersed, and

commenced feeding quickly about it. We did not wait to see them return, as

we had a long day's journey before us. Behind the house the hill seemed

alive with grouse, crowing in the morning sun. My hound came out baying

joyously to see me, and we started on our day's journey. Our road took us

through birch-woods, fragrant from the yesterday's rain, and in which the

birds sang right merrily. As we descended the river we passed the

plantations at Dalmigaire and considerable tracts of corn-ground — the

corn in this high country being still perfectly green. Here and there was

a small farm-house on a green mound, with a peat-stack larger than the

house itself. As we passed these, a bare-headed and bare-legged urchin

would look at us round a corner of the building, and then running in,

would bring out the rest of the household to stare at us. If we entered

one of the houses, we were always greeted with hospitable smiles, and the

good wife, wiping a chair with her apron, would produce a bowl of

excellent milk (such milk as you only can get in the Highlands) and a

plate of cheese and oat-cake, the latter apparently consisting of chopped

straw, and seasoned with gravel, though made palatable by the kind welcome

with which it was given. Frequently, too, a bottle of whisky would be

produced, and a glass of it urged on us, or we were pressed to stop to

take an egg or something warm. At Freeburn we parted — my friend to go by

coach to Inverness, and I to keep my course down the river, which is

surrounded by dreary grey hills. As I got on, however, the banks grew more

rocky and picturesque, enlivened here and there by the usual green patches

of corn, and the small farm-houses, with their large peat-stack, but

diminutive corn-stack. Near Freeburn I talked to an old Highlander, who

was flogging the water with a primitive-looking rod and line and a

coarse-looking fly, catching, however, a goodly number of trout. He was

the first angler I had as yet passed, with the exception of a kilted boy,

belonging to the shepherd at our place of rest, who was already out when

we left home, catching trout for his own breakfast and that of a young

peregrine falcon which he had caught in the rocks opposite the house, and

was keeping wholly on a fish diet, and a more beautiful and finer bird I

never saw, although she had fed for many weeks on nothing but small trout,

a food not so congenial to her as rabbits and pigeons and the other

products of the low country. I bought the hawk of him, and have kept her

ever since. Below Freeburn I had to wade the river, in order to avoid a

very difficult and somewhat dangerous pass on the rocks. Frequently I met

with fresh tracks of the otter. In some places, where the water fell over

rocks of any height, so as to prevent the animal from keeping the bed of

the river, there were regularly hard beaten paths by which they passed in

going from one pool to the other. The water-ouzel, too, enlivened the

scene by its curious rapid flight and shrill cry, as it flew from one

shallow to another, or passed back over my head to return to its favourite

resting-stone from which I had disturbed it.

The kestrel seems to abound

in the rocks through which the river runs, as I saw this bird very

frequently either sitting on some projecting angle of stone or hovering

high above me.

The country here appears as

good for grouse as the hills near the sources would be for red-deer, were

they free from sheep. I do not know a district in Scotland that would make

a better deer-forest than that immediately round and to the westward of

Coignafern, where the Monaghliahd mountains afford every variety of ground

suited to these animals, with most excellent feeding for them along the

burns and straths which intersect the high grounds in every direction, and

the most perfect solitude. It is almost a pity that the MacIntosh does not

turn this district into a forest.

|