|

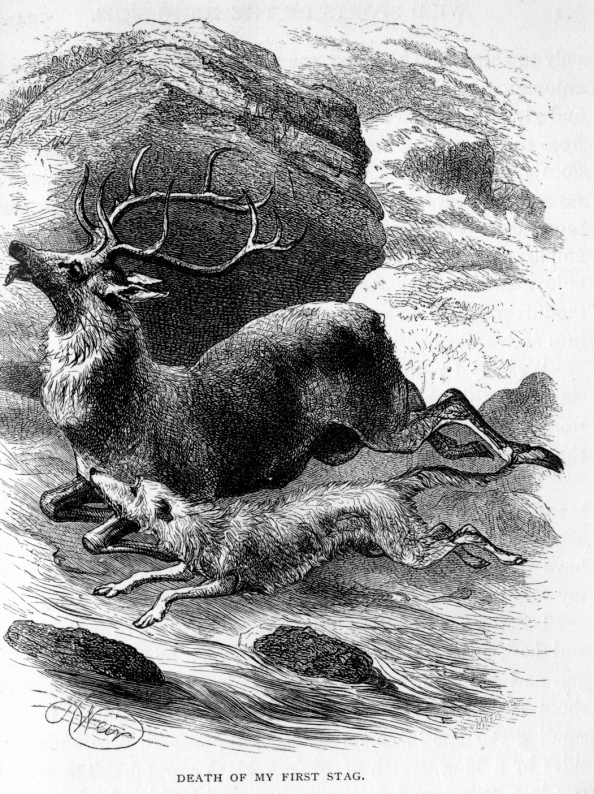

Death of my First Stag.

Where is the man who does

not remember and look back with feelings of energy and delight to the day,

the hour, and the wild scene, when he killed unaided his first stag? Of

course, I refer only to those who have the same love of wild sport, and

the same enjoyment in the romantic solitude and scenery of the mountain

and glen that I have myself; shooting tame partridges and hares from the

back of a well-trained shooting-pony in a stubble field does not, in my

eyes, constitute a sportsman, though there is a certain interest attached

even to this kind of pursuit, arising more from observing the cleverness

and instinct of the dogs employed than in killing the birds. But far

different is the enjoyment derived from stalking the red deer in his

native mountain, where every energy of the sportsman must be called into

active use before he can command success.

Well do I remember the

mountain side where I shot my first stag, and though many years have since

passed by, I could now, were I to pass through that wild and lovely glen,

lay my hand on the very rock under which he fell.

Though a good rifle-shot,

indeed few were much better, there seemed a charm against my killing a

deer. On two occasions, eagerness and fear of missing shook my hand when I

ought to have killed a fine stag. The second that I ever shot at came in

my way in a very singular manner.

I had been looking during

the chief part of the day for deer, and had, according to appointment, met

an attendant with my gun and pointers at a particular spring in the hills,

meaning to shoot my way home. This spring was situated in the midst of a

small green spot, like an oasis in the desert, surrounded on all sides by

a long stretch of broken black ground. The well itself was in a little

round hollow, surrounded by high banks.

I was resting here, having

met my gillie, and was consoling myself for my want of success by smoking

a cigar, when, at the same moment, a kind of shadow came across me, and

the pointers who were coupled at my feet pricked up their ears and

growled) with their eyes fixed on some object behind me. My keeper, who

had been out with me all day, was stretched on his back, in a half

slumber, and the gillie was kneeling down taking a long draught at the

cool well, with the enjoyment of one who had had a long toiling walk on a

hot August day. Turning my head lazily to see what had roused the dogs,

and had cast its shadow across me, instead of a shepherd, as I

expected—could I believe my eyes - there stood a magnificent stag, with

the fine shaped horns peculiar to those of the Sutherland forests. He was

standing on the bank immediately behind me, and not above fifty yards off,

looking with astonishment at the group before him, who had taken

possession of the very spot where he had intended to slake his thirst. The

deer seemed too much astonished to move, and for a moment I was in the

same dilemma. The rifle was on the around just behind the slumbering

Donald. I was afraid the deer would be off out of sight if I got up to

take it, or if I called loud enough to awake Donald. So I was driven to

the necessity of giving him a pretty severe kick, which had the effect of

making him turn on his side, and open his eyes with a grunt. "The rifle,

Donald, the rifle," I whispered, holding out my hand. Scarcely knowing

what he was at, he instinctively stretched out his hand to feel for it,

and held it out to me. All this takes some time to describe, but did not

occupy a quarter of a minute. At the same instant that I got the rifle,

the gillie lifted up his head from the water, and half turning, saw the

stag, and also saw that I was about to shoot at him. With a presence of

mind worthy of being better seconded, he did not raise himself from his

knees, but remained motionless with his eyes fixed on the deer. As I said

before, I had never killed a deer, and my hand shook and my heart beat. I

fired, however, with, as I thought, a good aim at his shoulder. The deer

at the instant turned round. After firing my shot, we all (including

Donald, who by this time comprehended what was going on) ran to the top of

the bank to see what had happened, as the deer disappeared the instant I

fired. I had, I believe, missed him altogether, though he looked as large

as an ox, and we saw him going at a steady gallop over the wide flat.

Donald had out the glass immediately, and took a steady sight at him, but

having watched the noble animal, as he galloped up the opposite slope and

stood for two or three minutes on the summit, looking back intently at us,

he shut up the telescope with a jerk that threatened to break every glass

in it, and giving a grunt, vastly expressive of disgust, returned to the

well, where he took a long draught. His only remark at the time was "

There's no the like of that stag in the country; weel do I mind seeing him

last year when shooting ptarmigan up yonder, and not a bullet had I. The

deil's in the rifle, that she did na kill him; and he'll cross the river

before he stops." It required some time and some whisky also to restore

Donald to his usual equanimity.

This was on a Saturday. On

the Monday following, at a very early hour, Donald appeared, and after his

morning salute of "It's a fine day, Sir," he added, "There will be some

deer about the west shoulder of the hill above Alt-na-cahr. Whenever the

wind is in the airt it now is, they feed about the burn there." We agreed

to walk across to that part of the ground, and were soon en route. Bran

galloped round us, baying joyously, as if he expected we should have good

luck. We had not gone half-a-mile from the house when we met one of the

prettiest girls in the country, tripping along the narrow path, humming a

Gaelic air, and looking bright and fresh as the morning. "How are you all

at home, Nanny, and how is your father getting on? does he see any deer on

the hill?" said I; her father was a shepherd not far from the house, and

she was then going down on some errand to my servants. "We are all no'

that bad, thank you, Sir, except mother, who still has the trouble on her.

Father says that he. saw some hinds and a fine stag yesterday as he

crossed the hill to the kirk; they were feeding on the top of Alt-na-cahr,

and did na mind him a bit."

Donald looked at me, with a

look full of importance, at this confirmation of his prophecy. "Deed, Sir,

that's a bonnie lass, and as gude as she is bonnie. It's just gude luck

our meeting her; if we had met that auld witch, her mother, not a beast

would we have seen the day." I have heard of Donald turning home again if

he met an old woman when starting on any deer-stalking excursion. The

young pretty girl, however, was a good omen in his eyes. We passed through

the woods, seeing here and there a roebuck standing gazing at us as we

crossed some grassy glade where he was feeding. On the rocks near the top

of the woods Donald took me to look at a trap he had set, and in it we

found a beautiful marten cat, which we killed, and hid amongst the

stones—another good omen in Donald's eyes.

On we went, taking a

careful survey of the ground here and there. At a loch whose Gaelic name I

do not remember, we saw a vast number of wild ducks, and at the farther

extremity of it a hind and calf feeding. We waited here for some time, and

I amused myself with watching the two deer as they fed, unconscious of our

neighbourhood, and from time to time drank at the burn which supplied the

loch. We then passed over a long dreary tract of brown and broken ground,

till we came to the picturesque-looking place where we expected to find

the deer—a high conical hill, rising out of rather flat ground, which gave

it an appearance of being of a greater height than it really was. We took

a most careful survey of the slope on which Donald expected to see the

deer. Below was an extensive level piece of heather with a burn running

through it in an endless variety of windings, and fringed with green

rushes and grass, which formed a strong contrast to the dark-coloured moor

through which it made its way, till it emptied itself into a long narrow

loch, beyond which rose Bar Cleebrich and some more of the highest

mountains in Scotland. In vain we looked and looked, and Donald at last

shut up his telescope in despair; "They are no' here the day," was his

remark. "But what is that, Donald?" said I, pointing to some

bluish-looking object I saw at some distance from us rising out of the

heather. The glass was turned towards it, and after having been kept

motionless for some time, he pronounced it to be the head and neck of a

hind. I took the glass, and while I was looking at it, I saw a fine stag

rise suddenly from some small hollow near her, stretch himself, and lie

down again. Presently six more hinds, and a two-year old stag got up, and

after walking about for a few minutes, they, one by one, lay down again,

but every one seemed to take up a position commanding a view of the whole

country We crept back a few paces, and then getting into the course of the

burn, got within three hundred yards of the deer, but by no means whatever

could we get nearer. The stag was a splendid fellow, with ten points, and

regular and fine-shaped horns. Bran winded them, and watched us most

earnestly, as if to ask why we did not try to get at them. The sensible

dog, however, kept quite quiet, as if aware of the importance, of not

being seen or heard. Donald asked me what o'clock it was; I told him that

it was just two. "Well, well, Sir, we must just wait here till three

o'clock, when the deer will get up to feed, and most likely the brutes

will travel towards the burn. The Lord save us, but yon's a muckle beast."

Trusting to his experience, I waited patiently, employing myself in

attempting to dry my hose by wringing them, and placing them in the sun.

Donald took snuff and watched the deer, and Bran laid his head on his paws

as if asleep, but his sharp eye and ear, pricked up on the slightest

movement, showed that he was ready for action at a moment's warning. As

nearly as possible at three o'clock they did get up to feed : first the

hinds rose and cropped a few mouthfuls of the coarse grass near them,

looking at and waiting for their lord and master, who, however, seemed

lazily inclined, and would not move; the young stag fed steadily on

towards us.

Frequently the hinds

stopped and turned back to their leader, who remained quite motionless,

excepting that now and then he scratched a fly off his flank with his

horn, or turned his head towards the hill side when a grouse crowed or a

plover whistled. The young stag was feeding quietly within a hundred and

fifty yards of us, and we had to lie flat on the ground now and then to

escape his observation. The evening air already began to feel chill, when

suddenly the object of our pursuit jumped up, stretched himself, and began

feeding. Not liking the pasture close to him, he trotted at once down into

the flat ground right away from us. Donald uttered a Gaelic oath, and I

fear I added an English one.

The stag that had been

feeding so near us stood still for a minute to watch the others, who were

all now several hundred yards away, grazing steadily. I aimed at him, but

just as I was about to fire he turned away, leaving nothing but his haunch

in view, and went after the rest. Donald applauded me for not shooting at

him, but told me that our case was hopeless, and that we had better make

our way home and attempt no more, as they were feeding in so open a place

that it was impossible to get at them : even Bran yawned and rose, as if

he too had given up all hope. "I will have one try, Donald; so hold the

dog." "You need na fash yoursel, Sir: they are clean out of all hope and

reason." I determined to make an effort before it became dusk; so leaving

Donald, I set off down the burn, looking for some hollow place that might

favour my getting up to them, but I could find none: at last it struck me

that I might by chance get up within a long shot by keeping a small

hillock, which was in the middle of the plain, between me and the deer.

The hillock was not two feet high, and all depended on the animals keeping

together and not outflanking me.

On I went, not on my hands

and knees, but crawling like a snake, and never rising even to my knee. I

could see their hindquarters as they walked away, feeding, however, most

eagerly, and when they looked up I lay still flatter on the ground with my

face buried in the heather. They appeared, however, not to suspect danger

in the open plain, but often looked anxiously towards the burn or the

rocky side of the mountain. One old long-legged hind kept me in a constant

state of alarm, as she frequently looked in my direction, turning her ears

as if to catch some suspicious sound. As for the stag, he never looked

about him once, leaving that to the hinds. I at last got within about a

hundred yards of the whole of them: as they fed in a group turned away

from me, I could not get a shot at anything but their hind-quarters, and I

did not wish to shoot unless I could get a fair broadside towards me.

While waiting for an opportunity, still flat on the ground, a grouse cock

walked out of the heather close to me, and strutted on with head erect and

his bright eye fixed on me till he came to a little hillock, where he

stopped and began to utter a note of alarm. Instantly every deer left off

eating. I saw that no time was to be lost and raised myself on my elbow,

and with cocked rifle waited for the hinds to move, that I might get at

the stag, who was in the midst of them. The hinds soon saw me and began to

trot away, but their leader seemed determined to see what the danger was,

and before he started turned round to look towards the spot where the

grouse was, giving me a good slanting shot at his shoulder. I immediately

touched the trigger, feeling at the same time sure of my aim. The ball

went true, and down he fell. I began reloading, but before I had half done

the stag was up again and making play after the hinds, who were galloping

up a gentle slope of the hill. The poor beast was evidently moving with

the greatest difficulty and pain; sometimes coming to his knees, and then

recovering himself with a strong effort, he still managed to keep not far

behind them. I sat down in utter despair: looking round too for Donald and

Bran, I could see nothing of them. Between anxiety and vexation I did not

know what to do. All at once I saw the hinds dash away in different

directions, and the next moment my gallant Bran appeared in the midst of

them. I shouted with joy. On came the dog, taking no notice of the hinds,

but making straight for the stag, who stood still for one instant, and

then rushed with apparently full vigour down the hill. Down they came

towards the burn, the dog not five yards behind the stag, but unable to

reach his shoulder (the place where he always struck his game). In a few

moments deer and hound went headlong and seemingly both together into the

burn. Donald appeared running like a lunatic : with good judgment he had,

when I left him, gone to cut off the deer in case I wounded one and it

took up the hill. As good luck would have it, the hinds had led off the

stag right up to where Donald and Bran were, notwithstanding his

inclination to go the other way. I ran to see what had become of them in

the burn, expecting to find the stag at bay. When I got there, however, it

was all over.

The deer had probably

tumbled from weakness, and Bran had got his fangs well into the throat of

the poor brute before he could rise again. The gallant dog, when I was up

with him, lay down panting with his fore-paws on the deer, and wagging his

tail, seemed to congratulate me on my victory, and to expect to be

caressed for his share in it. A fine stag he was, in perfect order, with

noble antlers. Donald added to my satisfaction by applauding my manner of

getting up to him, adding that he never would have thought it possible to

kill a stag on such bare and flat ground. Little did I feel the fatigue of

our three hours walk, two of them in the dark and hard rain. We did not go

home, but went to a shepherd's house, whose inhabitants were at evening

prayer when we arrived: we did not interrupt them, but afterwards the wife

prepared us a capital supper of eggs and fresh trout, which we devoured

with vast relish before the bright peat-fire, our wet clothes steaming all

the time like a boiler. Such was the death of my first stag. |