|

Wild Ducks: Edible kinds of — Breeding-places of Mallards — Change of

Plumage — Shooting —Feeding-places — Half-Bred Wild Ducks — Anas

glacialis — Anas clangula: Habits of — Teeth of Goosander — Cormorants —

Anecdotes.

A few years ago I used to

see a great many scaup ducks in the pools and burns near the coast, but

now it is very seldom that I meet with a single bird of this kind; the

last which I killed here was in the month of July. This is one of the few

ducks frequenting the shore which has not a rank or fishy flavour: out of

the numerous varieties of birds of the duck kind, I can only enumerate

four that are really good eating, namely, the common mallard, the widgeon,

the teal, and the scaup duck. The best of these is the mallard : with us

they breed principally about the most lonely lochs and pools in the hills;

sometimes I have seen these birds during the breeding-season very far up

among the hills : a few hatch and rear their young about the rough ground

and mosses near the sea, but these get fewer and fewer every year, in

consequence of the increase of draining and clearing which goes on in all

the swamps and wild grounds.

Some few breed in

furze-bushes and quiet corners near the mouth of the river, and may be

seen in some rushy pool, accompanied by a brood of young ones. Though so

wild a bird, they sit close, allowing people to pass very near to them

without moving. When they leave their nest, the eggs are always carefully

concealed, so that a careless observer would never suppose that the heap

of dried leaves and grass that he sees under a bush covers twelve or

thirteen duck's eggs.

Occasionally a wild duck

fixes on a most unlikely place to build her nest in; for instance, on a

cleft of a rock, where you would rather expect to find a pigeon or jackdaw

building, and I once, when fishing in a quiet brook in England, saw a wild

duck fly out of an old pollard oak-tree. My curiosity being excited by

seeing the bird in so unusual a place, I examined the tree, and found that

she had a nest built of sticks and grass, containing six eggs, placed at

the junction of the branches and the main stem. I do not know how she

would have managed to get her young ones safely out of it when hatched,

for on carefully measuring the height, I found that the nest was exactly

fifteen feet from the ground.

As soon as hatched, the

young ones take to the water, and it is very amusing to see the activity

and quickness which the little fellows display in catching insects and

flies as they skim along the surface of the water, led on by the parent

bird, who takes the greatest care of them, bustling about with all the

hurry and importance of a barn-yard hen. Presently she gives a low warning

quack, as a hawk or carrion crow passes in a suspicious manner over them.

One cry is enough, away all the little ones dart into the rushes,

screaming and fluttering, while the old bird, with head flat on the water

and upturned eye, slowly follows them, but not until she sees them all out

of danger. After a short time, if the enemy has disappeared, the old bird

peers cautiously from her covert, and if she makes up her mind that all is

safe, she calls forth her offspring again, to feed and sport in the open

water.

The young birds do not fly

till they are quite full grown. I have observed that, as soon as ever the

inner side of the wing is fully clothed, they take to flying; their bones,

which before this time were more like gristle than anything else, quickly

hardening, and giving the bird full power and use of its pinions. The old

bird then leads them forth at night to the most distant feeding-places,

either to the grass meadows where they search for snails or worms, or to

the splashy. swamps, where they dabble about all night, collecting the

different insects and young frogs that abound in these places. As the corn

ripens, they fly to the oat-fields in the dusk of the evening, preferring

this grain and peas to any other. They are now in good order and easily

shot, as they come regularly to the same fields every night. As soon as

they have satisfied their hunger, they go to some favourite pool, where

they drink and wash themselves. After this, they repair, before dawn, to

their resting-place for the day, generally some large piece of water,

where they can float quietly out of reach of all danger. In October the

drakes have acquired their splendid plumage, which they cast off in the

spring, at that time changing their gay feathers for a more sombre brown,

resembling the plumage of the female bird, but darker. During the time

that they are clothed in this grave dress, the drakes keep in flocks

together, and show themselves but little, appearing to keep as much out of

observation as possible. During the actual time of their spring moulting,

the drakes are for some days so helpless that I have frequently seen a dog

catch them. The same thing occurs with the few wild geese that breed in

the north of Scotland. With regard to shooting wild ducks, I am no

advocate or follower of the punt and swivel system. I can see little

amusement in taking a long shot at the sound of feeding water-fowl,

killing and maiming you know not what; nor am I addicted to punting myself

in a flat boat over half frozen mud, and waiting for hours together for

the chance of a sweeping shot. There may be great sport in this kind of

proceeding, but I cannot discover it. I much prefer the more active and

independent amusement of taking my chance with a common gun, meeting the

birds on their way to and from their feeding or resting places, and

observing and taking note of their different habits and ways of getting

their living.

No rule can be laid down

for wild-fowl shooting; what succeeds in one place fails in another. The

best plan, in whatever district the sportsman is located is to take note

where the birds feed, where they rest in the daytime, and where they take

shelter in heavy winds. By observing these different things it is always

easy enough to procure a few wild ducks. On the coast, the birds change

their locality with the ebb and flow of the tide, generally feeding with

the ebb, and resting with the flow. I believe that about the best

wild-fowl shooting in the kingdom is in the Cromarty Firth, where

thousands of birds of every variety pass the winter, feeding on the long

sea-grass, and passing backwards and forwards constantly at every turn of

the tide. I have here often killed wild ducks by moonlight. It is an

interesting walk in the bright clear winter nights, to go round by the

shore, listening to the various calls of the birds, the constant quack of

the mallard, the shrill whistle of the widgeon, the low croaking note of

the teal, and the fine bugle voice of the wild swan, varied every now and

then by the loud whistling of a startled curlew or oyster-catcher. The

mallard and teal are the only exclusively night-feeding birds; the others

feed at any time of the night or day, being dependent on the state of the

tide to get at the banks of grass and weed, or the sands where they find

shell-fish. All ducks are quite as wary in the bright moonlight as in the

day time, but at night are more likely to be found near the shore. Between

the sea and the land near my abode is a long stretch of green embankment,

which was made some years back in order to reclaim from the sea a great

extent of land, which then consisted of swampy grass and herbage,

overflowed at every high tide, but which now repays the expense of

erecting the embankments, by affording as fine a district of corn-land as

there is in the kingdom. By keeping the landward side of this grass-wall,

and looking over it with great care, at different spots, I can frequently

kill several brace of ducks and widgeon in an evening; though, without a

clever retriever, the winged birds must invariably escape. Guided by their

quacking, I have also often killed wild ducks at springs and running

streams in frosty nights. It is perfectly easy to distinguish the birds as

they swim about on a calm moonlight night, particularly if you can get the

birds between you and the moon. It is a great assistance in night shooting

to paste a piece of white paper along your gun-barrel, half-way down from

the muzzle. In the stillness of the night the birds are peculiarly alive

to sound, and the slightest noise sends them immediately out of shot.

Their sense of smelling being also very acute, you must always keep to

leeward of them. The mallard duck is more wary than any other kind in

these respects, rising immediately with loud cries of warning, and putting

all the other birds within hearing on the alert. I have seen the wild

swans at night swim with a low cheeping note close by me ; their white

colour, however, makes them more difficult to distinguish than any other

bird. It is quite easy to shoot ducks flying by moonlight, as long as you

can get them between you and the clear sky. Practice, however, is required

to enable the shooter to judge of distance at night time.

I have frequently caught

and brought home young wild ducks. If confined in a yard, or elsewhere,

for a week or two with tame birds, they strike up a companionship which

keeps them from wandering when set at liberty. Some few years back I

brought home three young wild ducks : two of them turned out to be drakes.

I sent away my tame drakes, and, in consequence, the next season had a

large family of half-bred and whole wild ducks, as the tame and wild breed

together quite freely. The wild ducks which have been caught are the

tamest of all; throwing off all their natural shyness, they follow their

feeder, and will eat corn out of the hand of any person with whom they are

acquainted. The half-bred birds are sometimes pinioned, as they are

inclined to fly away for the purpose of making their nests at a distance :

at other times they never attempt to leave the field in front of the

house. A pair or two always breed in the flower-garden. They appear to

have a great penchant for forming their nests in certain flowerbeds, and

they are allowed to have their own way in this respect, as their elegant

and high-bred appearance interests even the gardener, enemy as he is to

all intruders on his favourite flowers.

These birds conceal their

eggs with great care, and I have often been amused at the trouble the poor

duck is put to in collecting dead leaves and straw to cover her eggs, when

they are laid in a well-kept flower-bed. I often have a handful of straw

laid on the grass at a convenient distance from the nest, which the old

bird soon carries off, and makes use of. The drakes, though they take no

portion of the nesting labours, appear to keep a careful watch near at

hand during the time the duck is sitting. The half-bred birds have a

peculiarity in common with the wild duck—which is, that they always pair,

each drake taking charge of only one duck—not, as is the case with the

tame ducks, taking to himself half-a-dozen wives. The young, too, when

first hatched, have a great deal of the shyness of wild ducks, showing

itself in a propensity to run off and hide in any hole or corner that is

at hand. When in full plumage my drakes also have the beautifully mottled

feathers above the wing which are so much used in fly-dressing. With

regard to the larder, the half-wild ducks are an improvement on both the

tame and wild, being superior to either in delicacy and flavour. Their

active and neat appearance, too, make them a much more ornamental object

(as they walk about in search of worms on the lawn or field) than a

waddling, corpulent barn-yard duck.

There is a very pretty and

elegant little duck, which is common on our coast—the long-tailed duck,

Anas glacialis. Its movements and actions are peculiarly graceful and

amusing, while its musical cry is quite unlike that of any other bird,

unless a slight resemblance to the trumpeting of the wild swan may be

traced in it. Lying concealed on the shore, I have often watched these

birds as they swim along in small companies within twenty yards of me; the

drake, with his gay plumage, playing quaint antics round the more sad-coloured

female—sometimes jerking himself half out of the water, at others diving

under her, and coming up on the other side. Sometimes, by a common

impulse, they all set off swimming in a circle after each other with great

rapidity, and uttering their curious cry, which is peculiarly wild and

pleasing. When feeding, these birds dive constantly, remaining under water

for a considerable time. Turning up their tails, they dip under with a

curious kind of motion, one after the other, till the whole flock is under

water. They are not nearly so wild or shy as many other kinds of

wild-fowl, and are easily shot, though if only winged it is almost

impossible to catch them, even with the best retriever, so. quickly do

they dive. They swim in with the flowing tide, frequently following the

course of the water to some little distance from the mouth of the river.

When I see them in the heavy surf on the main shore, they seem quite at

their ease, floating high in the water, and diving into the midst of the

wildest waves. When put up, they seldom fly far, keeping low, and suddenly

dropping into the water again, where they seem more at their ease than in

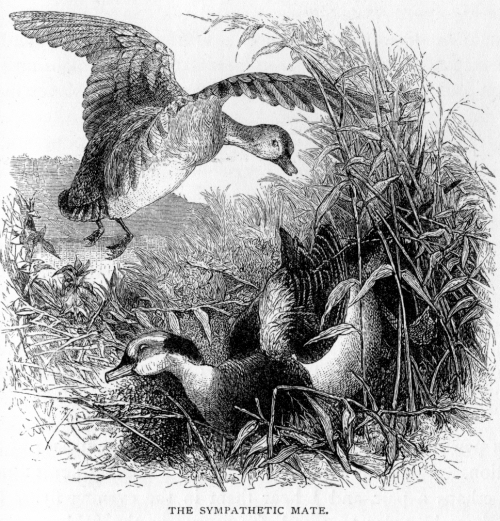

the air. When I have shot one of these birds, its mate (whether the duck

or the drake is the survivor) returns frequently to the spot, flying round

and round, and uttering a plaintive call.

On the open part of the

coast they are often seen in company with the velvet duck. The latter very

seldom comes into the bay, but keeps without the bar, quite regardless of

storm or wind. It is a fine handsome bird, though of a rather heavy make.

When flying, they have very much the appearance of a black-cock, having

the same white mark on the wing, and being black in all other parts of

their plumage. It is not difficult to approach these birds in a boat, but

as they are not fit to eat, they are not much sought after. They are

excellent divers, and must be shot dead, or they generally escape.

The golden-eye, Anas

clangula, and the morillon, are common about the mouth of the river

and burns. I have often heard it argued that these two birds are merely

the same species in different degrees of maturity; but I do not consider

that there is the least doubt as to their being quite distinct. I have

frequently shot what I suppose to be the young golden-eye not arrived at

its full plumage ; but in these the white spot at the corner of the mouth

is more or less visible. The birds are larger than the morillon, besides

which the golden-eye, in whatever stage of maturity it is found, always

makes that peculiar noise with its wings, when flying, which is not heard

in the flight of the morillon, or of any other kind of duck. I remember

too, once watching a pair of morillons in a Highland loch, late in the

spring ; they had evidently paired, and were come to the age of maturity,

and ready for breeding.

The golden-eye dives well,

remaining a considerable time under water seeking its food, which consists

of the small shellfish which it finds at the bottom. The morillon

frequents the same places as the golden-eye, but always remains singly or

in pairs, whereas the latter birds frequently unite in small flocks,

paiticularly when they take to the inland lochs, which they do at the

commencement of the spring. The golden-eye is frequently very fat and

heavy, but is of a rank, coarse flavour.

The goosander and merganser

fish constantly in the river: they remain late in the spring and return

early in the autumn. Quick-sighted, they perceive an enemy at a great

distance, and keep a watch on all his movements. As long as he remains in

full view and at a safe distance the birds do not move; but the moment the

sportsman conceals himself, or approaches too near, they rise and go out

to sea. They are easily killed by sending a person above them, and

concealing oneself some way down the course of the stream, as when put up,

although they may at first fly a short way up the water, they invariably

turn downwards and repair to the open sea, following the windings of the

river during their whole flight. If winged, they instantly dive, and rise

at a considerable distance, keeping only their heads above the water, and

making for the sea as fast as they can.

They feed on small trout

and eels, which they fish for at the tails of the streams or in

comparatively shallow water, unlike the cormorant, who, feeding on

good-sized fish, is always seen diving in the large deep pools, where they

are more likely to find trout big enough to satisfy their voracious

appetite. The throat of the cormorant stretches to a very great extent,

and their mouth opens wide enough to swallow a good-sized sea-trout. I saw

a cormorant a few days ago engaged with a large white trout which he had

caught in a quiet pool, and which he seemed to have some difficulty in

swallowing. The bird was swimming with the fish across his bill, and

endeavouring to get it in the right position, that is, with the head

downwards. At last, by a dexterous jerk, he contrived to toss the trout

up, and, catching it in his open mouth, managed to gulp it down, though

apparently the fish was very much larger in circumference than the throat

of the bird. The expanding power of a heron's throat is also wonderfully

great, and I have seen it severely tested when the bird was engaged in

swallowing a flounder something wider than my hand. As the flounder went

down, the bird's throat was stretched out into a fan-like shape, as he

strained, apparently half-choked, to swallow it. These fish-eating birds

having no crop, all they gulp down, however large it may be, goes at once

into their stomach, where it is quickly digested. Like the heron, the

cormorant swallows young water-fowl, rats, or anything that comes in its

way.

There is a peculiarity in

the bills of most birds which live on worms or fish : they are all more or

less provided with a kind of teeth, which, sloping inwards, admit easily

of the ingress of their prey, but make it impossible for anything to

escape after it has once entered. In the goosander and merganser this is

particularly conspicuous, as their teeth are so placed that they hold

their slippery prey with the greatest facility. The common wild duck has

it also, though the teeth are not nearly so projecting or sharp feeding as

it does on worms and insects, it does not require to be so strongly armed

in this respect as those birds that live on fish.

I wonder that it has never

occurred to any one in this country to follow the example of the Chinese

in teaching the cormorant to fish. The bold and voracious disposition of

this bird makes it easy enough to tame, and many of our lochs and

river-mouths would be well adapted for a trial of its abilities in

fishing; and it would be an amusing variety in sporting to watch the bird

as he dived and pursued the fish in clear water. We might take a hint from

our brethren of the Celestial Empire with some advantage in this respect.

A curious anecdote of a

brood of young wild ducks was told me by my keeper to-day. He found in

some very rough, marshy ground, which was formerly a peat-moss, eight

young ducks nearly full-grown, prisoners, as it were, in one of the old

peat-holes. They had evidently tumbled in some time before, and had

managed to subsist on the insects, etc., that it contained or that fell

into it. From the manner in which they had undermined the banks of their

watery prison, the birds must have been in it for some weeks. The sides

were perpendicular, but there were small resting-places under the bank

which prevented their being drowned. The size of the place they were in

was about eight feet square, and in this small space they had not only

grown up, but thrived, being fully as large and heavy as any other young

ducks of the same age.

In shooting water-fowl, I

have often been struck by the fact that as soon as ever life is extinct in

a bird which falls in the sea or river, the plumage begins to get wet and

to be penetrated by the water, although as long as the bird lives it

remains dry and the wet runs off it. I can only account for this by

supposing that the bird, as long as life remains, keeps his feathers in a

position throw off and prevent the water from entering between them. This

power is of course lost to the dead bird, and the water penetrating

through the outer part of the feathers wets them all. This appears to be

more likely than that the feathers should be only kept dry by the oil

supplied by the bird, as the effect of this oil could not be so

instantaneously lost as to admit of wet as soon as the bird drops dead,

while if the bird be only wounded they remain dry.

|