|

Anecdotes and Instinct of Dogs — Anecdotes of Retriever — Shepherds'

Dogs — Sagacity — Dogs and Monkey — Bulldog — Anecdotes of Shooting a

Stag — Treatment of Dogs.

So much has been written,

and so many anecdotes told, of the cleverness and instinct of dogs, that I

am almost afraid to add anything more on the subject, lest I should be

thought tedious. Nevertheless I cannot refrain from relating one or two

incidents illustrating the instinct, almost amounting to reason, that some

of my canine acquaintances have evinced, and which have fallen under my

own notice. Different dogs are differently endowed in this respect, but

much also depends on their education, manner of living, etc. The dog that

lives with his master constantly sleeping before his fire, instead of in

the kennel, and hearing and seeing all that passes, learns, if at all

quick-witted, to understand not only the meaning of what he sees going on,

but also, frequently in the most wonderful manner, all that is talked of.

I have a favourite retriever, a black water-spaniel, who for many years

has lived in the house, and been constantly with me; he understands and

notices everything that is said, if it at all relates to himself or to the

sporting plans for the day: if at breakfast-time I say, without addressing

the dog himself, "Rover must stop at home to-day, I cannot take him out,"

he never attempts to follow me; if, on the contrary, I say, however

quietly, "I shall take Rover with me to-day," the moment that breakfast is

over he is all on the qui vive, following me wherever I go, evidently

aware that he is to be allowed to accompany me. When left at home, he sits

on the step of the front door, looking out for my return, occasionally

howling and barking in an ill-tempered kind of voice; his great delight is

going with me when I hunt the woods for roe and deer. I had some covers

about five miles from the house, where we were accustomed to look for roe:

we frequently made our plans over night while the dog was in the room. One

day, for some reason, I did not take him: in consequence of this,

invariably when he heard us at night forming our plan to beat the woods,

Rover started alone very early in the morning, and met us up there. He

always went to the cottage where we assembled, and sitting on a hillock in

front of it, which commanded a view of the road by which we came, waited

for us: when he saw us coming, he met us with a peculiar kind of grin on

his face, expressing, as well as words could, his half doubt of being well

received, in consequence of his having come without permission: the

moment he saw that I was not angry with him, he threw off all his

affectation of shyness, and barked and jumped upon me with the most

grateful delight. As

he was very clever at finding deer, I often sent him with the beaters or

hounds to assist, and he always plainly asked me on starting whether he

was to go with me to the pass or to accompany the men. In the latter case,

though a very exclusive dog in his company at other times, he would go

with any one of the beaters, although a stranger to him, whom I told him

to accompany, and he would look to that one man for orders as long as he

was with him. I never lost a wounded roe when he was out, for once on the

track he would stick to it, the whole day if necessary, not fatiguing

himself uselessly, but quietly and determinedly following it up. If the

roe fell and he found it, he would return to me, and then lead me up to

the animal, whatever the distance might be. With red-deer he was also most

useful. The first time that he saw me kill a deer he was very much

surprised; I was walking alone with him through some woods in Ross-shire,

looking for woodcocks; I had killed two or three, when I saw such recent

signs of deer, that I drew the shot from one barrel, and replaced it with

ball. I then continued my walk. Before I had gone far, a fine barren hind

sprang out of a thicket, and as she crossed a small hollow, going directly

away from me, I fired at her, breaking her backbone with the bullet; of

course she dropped immediately, and Rover, who was a short distance behind

me, rushed forward in the direction of the shot, expecting to have to pick

up a woodcock; but on coming up to the hind, who was struggling on the

ground, he ran round her with a look of astonishment, and then came back

to me with an expression in his face plainly saying, " What have you done

now? —you have shot a cow or something." But on my explaining to him that

the hind was fair game, he ran up to her and seized her by the throat like

a bulldog. Ever afterwards he was peculiarly fond of deer-hunting, and

became a great adept, and of great use. When I sent him to assist two or

three hounds to start a roe—as soon as the hounds were on the scent, Rover

always came back to me and waited at the pass: I could enumerate endless

anecdotes of his clever feats in this way.

Though a most aristocratic dog in his usual

habits, when staying with me in England once, he struck up an acquaintance

with a rat catcher and his curs, and used to assist in their business when

he thought that nothing else was to be done, entering into their way of

going on, watching motionless at the rats' holes when the ferrets were in,

and, as the rat catcher told me, he was the best dog of them all, and

always to be depended on for showing if a rat was in a hole, corn-stack,

or elsewhere; never giving a false alarm, or failing to give a true one.

The moment, however, that he saw me, he instantly cut his humble friends,

and denied all acquaintance with them in the most comical manner.

The shepherds' dogs in the mountainous

districts often show the most wonderful instinct in assisting their

masters, who, without their aid, would have but little command over a

large flock of wild black-faced sheep. It is a most interesting sight to

see a clever dog turn a large flock of these sheep in whichever direction

his master wishes, taking advantage of the ground, and making a wide sweep

to get round the sheep without frightening them, till he gets beyond them,

and then rushing barking from flank to flank of the flock, and bringing

them all up in close array to the desired spot. When, too, the shepherd

wishes to catch a particular sheep out of the flock, I have seen him point

it out to the dog, who would instantly distinguish it from the rest, and

follow it up till he caught it. Often I have seen the sheep rush into the

middle of the flock, but the dog, though he must necessarily have lost

sight of it amongst the rest, would immediately single it out again, and

never leave the pursuit till he had the sheep prostrate, but unhurt, under

his feet. I have been with a shepherd when he has consigned a certain part

of his flock to a dog to be driven home, the man accompanying me farther

on to the hill. On our return we invariably found that he had either given

up his charge to the shepherd's wife or some other responsible person, or

had driven them, unassisted, into the fold, lying down himself at the

narrow entrance to keep them from getting out till his master came home.

At other times I have seen a dog keeping watch on the hill on a flock of

sheep, allowing them to feed all day, but always keeping sight of them,

and Brian them home at a proper hour in the evening. In fact it is

difficult to say what a shepherd's dog would not do to assist his master,

who would be quite helpless without him in a Highland district.

Generally speaking these Highland sheepdogs do

not show much aptness in learning to do anything not connected in some way

or other with sheep or cattle. They seem to have been brought into the

world for this express purpose, and for no other.

They watch their master's small crop of oats

or potatoes with great fidelity and keenness, keeping off all intruders in

the shape of sheep, cattle, or horses. A shepherd once, to prove the

quickness of his dog, who was lying before the fire in the house where we

were talking, said to me, in the middle of a sentence concerning something

else — "I'm thinking, Sir, the cow is in the potatoes." Though he

purposely laid no stress on these words, and said them in a quiet

unconcerned tone of voice, the dog, who appeared to be asleep, immediately

jumped up, and leaping through the open window, scrambled up the turf roof

of the house, from which he could see the potato-field. He then (not

seeing the cow there) ran and looked into the byre where she was, and

finding that all was right, came back to the house. After a short time the

shepherd said the same words again, and the dog repeated his look-out; but

on the false alarm being a third time given, the dog got up, and wagging

his tail, looked his master in the face with so comical an expression of

interrogation, that we could not help laughing aloud at him, on which,

with a slight growl, he laid himself down in his warm corner, with an

offended air, and as if determined not to be made a fool of again.

Occasionally a poaching shepherd teaches his

dog to be of great service in assisting him to kill game. I remember one

of these men, who was in the habit of wiring hares, and though the keepers

knew of his malpractices, they were for some time unable to catch him in

the act, in consequence of his always Placing his three dogs as videttes

in different directions, to warn him of the approach of any person. A

herd-boy at the farm near my house puts his dog to a curious use. A great

part of his flock are sent to pasture on the carse-ground across the

river, and when the boy does not want to go across to count them and see

that they are all right, deterred from doing so by the water being

flooded, or from any other reason, he sends his dog to swim across and

collect the sheep on the opposite bank, where he can see them all

distinctly. Though there are other sheep on the carse belonging to

different people, the dog only brings his own flock. After they are

counted and pronounced to be all right by the boy, the dog swims back

again to his master.

Were I to relate the numberless anecdotes of dogs that have been told me,

I could fill a volume. I am often amused by observing the difference of

temper and disposition which is shown by my own dogs—as great a

difference, indeed, as would be perceived among the same number of human

beings. Having for many years been a great collector of living pets, there

is always a vast number of these hangers-on about the house—some useful,

some ornamental, and some neither the one nor the other.

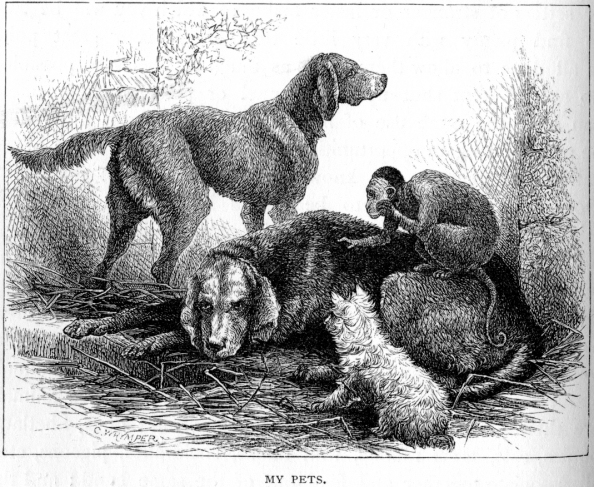

Opposite one window of the room I am in at

present are a monkey and five dogs basking in the sun, a bloodhound, a

Skye terrier, a setter, a Russian poodle, and a young Newfoundland bitch,

who is being educated as a retriever; they all live in great friendship

with the monkey, who is now in the most absurd manner searching the

poodle's coat for fleas, lifting up curl by curl, and examining the roots

of the hair. Occasionally, if she thinks that she has pulled the hair, or

lifted one of his legs rather too roughly, she looks the dog in the face

with an inquiring expression to see if he is angry. The dog, however,

seems rather to enjoy the operation, and showing no symptoms of

displeasure, the monkey continues his search, and when she sees a flea

catches it in the most active manner, looks at it for a moment, and then

eats it with great relish. Having exhausted the game on the poodle, she

jumps on the back of the bloodhound bitch, and having looked into her face

to see how she will bear it, begins a new search, but finding nothing,

goes off for a game at romps with the Newfoundland dog. While the

bloodhound bitch, hearing the voice of one of the children, whom she has

taken a particular fancy to, walks off to the nursery, the setter lies

dozing and dreaming of grouse; while the little terrier sits with ears

pricked up, listening to any distant sounds of dog or man that she may

hear; occasionally she trots off on three legs to look at the back door of

the house, for fear any rat-hunt or fun of that sort may take place

without her being invited. Why do Highland terriers so often run on three

legs particularly when bent on any mischief? Is it to keep one in reserve

in case of emergencies I never had a Highland terrier who did not hop

along constantly on three legs, keeping one of the hind legs up as if to

rest it. The Skye

terrier has a great deal of quiet intelligence, learning to watch his

master's looks, and understand his meaning in a wonderful manner. Without

the determined blind courage of the English bull terrier, this kind of dog

shows great intrepidity in attacking vermin of all kinds, though often his

courage is accompanied by a kind of shyness and reserve; but when once

roused by being bit or scratched in its attacks on vermin, the Skye

terrier fights to the last, and shows a great deal of cunning and

generalship, as well as courage. Unless well entered, when young, however,

they are very apt to be noisy, and yelp and bark more than fight. The

terriers which I have had of this kind show some curious habits, unlike

most other dogs. I have observed that when young they frequently make a

kind of seat under a bush or hedge, where they will sit for hours

together, crouched like a wild animal. Unlike other dogs too, they will

eat (though not driven by hunger) almost anything that is given them, such

as raw eggs, the bones and meat of wild-ducks, or wood-pigeons, and other

birds, that every other kind of dog, however hungry, rejects with disgust.

In fact, in many particulars, their habits resemble those of wild animals;

they always are excellent swimmers, taking the water quietly and

fearlessly when very young. In tracking wounded deer I have occasionally

seen a Skye terrier of very great use, leading his master quietly, and

with great precision, up to the place where the deer had dropped, or had

concealed himself; appearing too to be acting more for the benefit of his

master, and to show the game, than for his own amusement. I have no doubt

that a clever Skye terrier would in many cases get the sportsman a second

shot at a wounded deer with more certainty than almost any other kind of

dog. Indeed, for this kind of work, a quiet though slow dog often is of

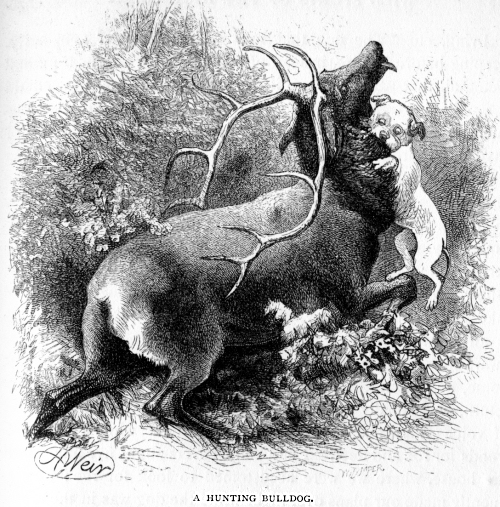

more use than the best deer-hound. I at one time had an English bulldog,

who accompanied me constantly in deerstalking; he learned to crouch and

creep up to the deer with me, never showing himself, and seemingly to

understand perfectly what I wished him to do. When necessary, I could

leave him for hours together, lying alone on the hill, when he would never

stir till called by me. If a deer was wounded, he would follow the track

with untiring perseverance, distinguishing the scent of the wounded

animal, and singling it out from the rest, never making a mistake in this

respect; he would also follow the stag till he brought him to bay, when,

with great address in avoiding the horns, he would rush in and seize him

either by the throat or the ear, holding on till I came up, or, as he once

did, strangling the animal, and then coming back to show me where he had

left it. In driving

some woods one day in Ross-shire, a fine stag broke into a wide opening;

two or three sportsmen were stationed at some distance above me; as the

deer passed, I saw the light puff of smoke, and heard the crack of their

rifles as they fired. At every shot the poor animal doubled with the most

extraordinary bounds; he tried to turn back to the cover from which he had

been driven, but the shouts of the beaters deterred him, and after

stopping for a moment to deliberate, he came back fully determined to

cross the opening, in order to gain the shelter of some large woods beyond

it. He was galloping across it, when crack went another rifle, the ball

striking with a splash into a small pool of water close to him; this

turned him towards me, and down he came in my direction as hard as he

could gallop; he appeared to be coming directly at me: just as he was

about a hundred yards from me, a shout from the beaters, who were coming

in view, turned him again, and he passed me, going ventre a terre, with

his head up and his horns back over his shoulders, giving me a good

broadside shot; I fired, and he reeled, turning half round. Bang went my

other barrel, and the stag rolled over like a rabbit, with a force and

crash that seemed as if it would have broken every bone in his body. Up he

got again, and went off, apparently as sound as ever, into the large wood,

passing close to a sportsman who was loading; when in the wood, we saw

him halt for a moment on a hillock and take a good steady look at us all,

who were lost in astonishment at his escape after having been so fairly

upset. He then went off at a steady swinging gallop, and we heard him long

after he was out of view crushing through the dry branches of the young

fir-trees. "Bring the dog," was the cry, and a very large animal,

something between a mastiff and a St. Bernard, was brought; the dog went

off for a little while, barking and making a great noise, but after

rushing up against half-a-dozen trees, and tumbling over amongst the

hidden stones, he came back limping and unwilling to renew the hunt. I had

left my bulldog with a servant at a point of the wood some distance off,

and I proposed sending for him; one of the sportsmen, who had never seen

him engaged in this kind of duty, sarcastically said, "What, that dog who

followed us to-day, as we rode up? He can be no use; he looks more fit to

kill cats or pin a bull." Our host, however, who was better acquainted

with his merits, thought otherwise; and when the bulldog came wagging his

tail and jumping up on me, I took him to the track and sent him upon it;

down went his nose and away he went as hard as he could go, and quite

silently. The wood was so close and thick that we could not keep him in

sight, so I proposed that we should commence our next beat, as the dog

would find me wherever I was, and the strangers did not seem much to

expect any success in getting the wounded stag. During the following beat

we saw the dog for a moment or two pass an opening, and the next instant

two deer came out from the thicket into which he had gone. "He is on the

wrong scent, after all," said the shooter who stood next to me. " Wait,

and we will see," was my answer.

We had finished this beat and were consulting

what to do when the dog appeared in the middle of us, appearing very well

satisfied with himself though covered with blood, and with an ugly tear in

his skin all along one side. " Ah !" said some one "he has got beaten off

by the deer." Looking at him, I saw that most of the blood was not his

own, the wound not being at all deep; I also knew that once having had

hold of the deer, he would not have let go as long as he had life in him.

"Where is he, old boy? take us to him," said I; the dog perfectly

understanding me, looked up in my face, and set off slowly with a whine of

delight. He led us through a great extent of wood, stopping every now and

then that we might keep up with him; at last he came to the foot of a rock

where the stag was lying quite dead with his throat torn open, and marks

of a goodly struggle all round the place; a fine deer he was too, and much

praise did the dog get for his courage and skill: I believe I could have

sold him on the spot at any price which I had chosen to ask, but the dog

and I were too old friends to part, having passed many years together,

both in London, where he lived with my horses and used to run with my cab,

occasionally taking a passing fight with a cat; and also in the country,

where he had also accompanied me in many a long and solitary ramble over

mountain and valley.

In choosing a young dog for a retriever, it is a great point to fix upon

one whose ancestors have been in the same line of business. Skill and

inclination to become a good retriever are hereditary, and one come of

good parents scarcely requires any breaking, taking to it naturally as

soon as he can run about. It is almost impossible to make some dogs useful

in this way; no teaching will do it unless there be a natural

inclination—a first-rite retriever nascitur non fit. You may break

almost any dog to carry a rabbit or bird, but it is a different thing

entirely to retrieve satisfactorily, or to be uniformly correct in

distinguishing and sticking to the scent of the animal which is wounded.

In the same way pointing is hereditary in

pointers and setters, and puppies of a good breed and of a well-educated

ancestry take to pointing at game as naturally as to eating their food,—

and not only do they, of their own accord, point steadily, but also back

each other, quarter their ground regularly, and in fact instinctively

follow the example of their high bred and well brought up ancestors. For

my own part, I think it quite a superfluous trouble crossing a good breed

of pointers with foxhound, or any other kind of dog, by way of adding

speed and strength,—you lose more than you gain, by giving at the same

time hard-headedness and obstinacy. It is much better, if you fancy your

breed of pointers or setters to be growing small or degenerate, to cross

them with some different family of pointers or setters of stronger or

faster make, of which you will be sure to find plenty with very little

trouble. It is a great point in all dogs to allow them to be as much at

liberty as possible; no animal kept shut up in a kennel or place of

confinement can have the same use of his senses as one who is allowed to

be at large to gain opportunities of exerting his powers of observation

and increase his knowledge in the ways of the world. Dogs who are allowed

to be always loose are very seldom mischievous and troublesome, it is only

those who are kept too long shut up and in solitude that rush into

mischief the moment they are at liberty; of course it is necessary to keep

dogs confined to a certain extent, but my rule is to imprison them as

little as possible. Mine, therefore, seldom are troublesome, but live at

peace and friendship with numerous other animals about the house and

grounds, although many of those animals are their natural enemies and

objects of chase: dogs, Shetland Ponies, cats, tame rabbits, wild ducks,

sheldrakes, pigeons, etc., all associate together and feed out of the same

hand; and the only one of my pets whose inclination to slaughter I cannot'

subdue, is a peregrine falcon, who never loses an opportunity of killing

any duck or hen that may venture within his reach. Even the wild

partridges and wood-pigeons, who frequently feed with the poultry, are

left unmolested by the dogs. The terrier, who is constantly at warfare

with cats and rabbits in a state of nature, leaves those about the house

in perfect peace; while the wildest of all wild fowl, the common mallards

and sheldrakes eat corn from the hand of the "hen-wife."

Though naturally all men are carnivorous, and

therefore animals of prey, and inclined by nature to hunt and destroy

other creatures, and although I share in this our natural instinct to a

great extent, I have far more pleasure in seeing these different animals

enjoying themselves about me, and in observing their different habits,

than I have in hunting down and destroying them.

|