|

The Hen Harrier: Destructiveness to game; Female of — Trapping — The

Sparrowhawk: Courage of; Ferocity; Nest — The Kestrel: Utility of — The

Merlin: Boldness — The Hobby — Increase of small

Birds.

IN the autumn my partridges

suffer much from the hen-harrier. As soon as the corn is cut this bird

appears, and hunts the whole of the low country in the most determined and

systematic manner. The hen-harrier, either on the hill-side or in the

turnip-field, is a most destructive hunter. Flying at the height of only a

few feet from the ground, he quarters the ground as regularly as an old

pointer, crossing the field in every direction; nor does he waste time in

hunting useless ground, but tries turnip-field after turnipfield, and

rushy field after rushy field, passing quickly over the more open ground,

where he thinks his game is not so likely to be found. The moment he sees

a bird, the hawk darts rapidly to a height of about twenty feet, hovers

for a moment, and then comes down with unerring aim on his victim,

striking dead with a single blow partridge or pheasant, grouse or

black-cock, and showing a strength not to be expected from his light

figure and slender though sharp talons.

I saw on a hill-side in

Ross-shire a hen-harrier strike a heath hen. I instantly drove him away,

but too late, as the head of the bird was cut as clean off by the single

stroke as if done with a knife. On another day, when passing over the hill

in the spring, I was attended by a hen-harrier for some time, who struck

down and killed two hen grouse that I had put up. Both these birds I

contrived to take from him; but a third grouse rose, and was killed and

carried off over the brow of a hill before I could get up to him. There is

no bird more difficult to shoot than this. Hunting always in the open

country, though appearing intent on nothing but his game, the wary bird,

with an instinctive knowledge of the range of shot, will keep always just

out of reach, and frequently carry off before your very face the partridge

you have flushed, and perhaps wounded.

There is a diversity of

opinion whether the hawk commonly called the ringtail is the female of the

hen-harrier. I have, however, no doubt at all on the subject. The ringtail

is nothing more than the female or young bird. The male does not put on

his blue and white plumage till he is a year old. I have frequently found

the nest both on the mountain, where they build in a patch of rough

heather, generally by the side of a burn, and also in a furze-bush. Though

very destructive to grouse and other game, this bird has one redeeming

quality, which is, that he is a most skilful rat-catcher. Skimming

silently and rapidly through a rick-yard, he seizes on any incautious rat

who may be exposed to view; and from the habit this hawk has of hunting

very late in the evening, many of these vermin fall to his share. Though

of so small and light a frame, the hen-harrier strikes down a mallard

without difficulty; and the marsh and swamp are his favourite

hunting-grounds. Quick enough to catch a snipe, and strong enough to kill

a mallard, nothing escapes him. Although so courageous in pursuit of game,

he is a wild, untamable bird in captivity; and though I have sometimes endeavoured to tame one, I could never succeed in rendering him at all

familiar. As he disdains to eat any animal not killed by himself, he is a

very difficult bird to trap. The best chance of catching him is in what is

called a pole-trap, placed on a high post in the middle of an open part of

the country; for this hawk has (in common with many others) the habit of

perching on upright railings and posts, particularly as in the open

plains, where he principally hunts, there are but few trees, and he seldom

perches on the ground. His flight is leisurely and slow when searching for

game; but his dart, when he has discovered his prey, is inconceivably

rapid and certain.

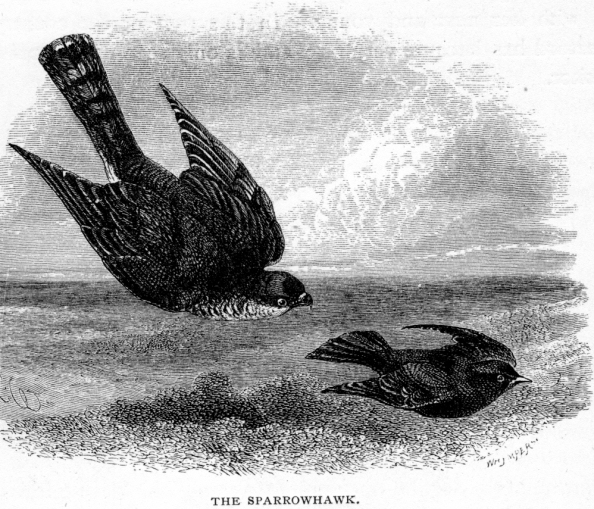

There is another most

destructive kind of hawk who frequently pays us a visit—the sparrowhawk.

Not content with the partridges and other ferae naturae, this bold little

freebooter invades the poultry-yard rather too frequently. The hens

scream, the ducks quack, and rush to the cover of the plantations; whilst

the tame pigeons dart to and fro amongst the buildings, but in vain. The

sparrowhawk darts like an arrow after one of the latter birds, and carries

it off, though the pigeon is twice or three times his own weight. The

woman who takes care of the poultry runs out, but is too late to see

anything more than a cloud of white feathers, marking the place where the

unfortunate pigeon was struck. Its remains are, however, generally found

at some little distance; and when this is the case, the hawk is sure to

be caught, as he invariably returns to what he has left, and my boys bring

the robber to me in triumph before many days elapse. Sometimes he returns

the same day to finish picking the bones of the bird, but often does not

come back for two or three. In the meantime, whatever part of the pigeon

he has left is pegged to the ground, and two or three rat-traps are set

round it, into one of which he always contrives to step. When caught,

instead of seeming frightened, he flies courageously at the hand put down

to pick him up, and fights with beak and talons to the last. Occasionally,

when standing still amongst the trees, or even when passing the corner of

the house, I have been startled by a sparrowhawk gliding rapidly past me.

Once one came so close to me, that his wing actually brushed my arm; the

hawk being in full pursuit of an unfortunate blackbird. On another

occasion, a sparrow-hawk pursued a pigeon through the drawing-room window,

and out at the other end of the house through another window, and never

slackened his pursuit, notwithstanding the clattering of the broken glass

of the two windows they passed through. But the most extraordinary

instance of impudence in this bird that I ever met with, was one day

finding a sparrowhawk deliberately standing on a very large pouter-pigeon

on the drawing-room floor, and plucking it, having entered in pursuit of

the unfortunate bird through an open window, and killed him in the room.

The sparrowhawk sometimes

builds on rocks, and sometimes in trees. Like all rapacious birds, he is

most destructive during the breeding-season. I have found a great quantity

of remains of partridges, wood-pigeons, and small birds about their nests,

though it has puzzled me to understand how so small a bird can convey a

wood-pigeon to its young ones. There is more difference in size between

the male and female sparrowhawk than between the different sexes of any

other birds of the hawk kind, the cock bird being not nearly so large or

powerful a bird as the hen. Supposing either male or female sparrowhawk to

be killed during the time of incubation, the survivor immediately finds a

new mate, who goes on with the duties of the lost bird, whatever stage of

the business is being carried on at the time, whether sitting on the eggs

or rearing the young.

The kestrel breeds commonly

with us about the banks of the river, or in an old crow's nest. This is a

very beautifully marked hawk, and I believe does much more good than harm.

Though occasionally depriving us of some of our lesser singing birds, this

hawk feeds principally, and indeed almost wholly, on mice. Any person who

knows a kestrel-hawk by sight must have constantly observed them hovering

nearly stationary in the air above a grass-field, watching for the exit

from its hole of some unfortunate field-mouse. When feeding their young, a

pair of kestrels destroy an immense number of these mischievous little

quadrupeds, which are evidently the favourite food of these birds. Being

convinced of their great utility in this respect, I never shoot at or

disturb a kestrel. It is impossible, however, to persuade a gamekeeper

that any bird called a hawk can be harmless; much less can one persuade

so opinionated and conceited a personage (as most keepers are) that a hawk

can be useful; therefore the poor kestrel generally occupies a prominent

place amongst the rows of bipeds and quadrupeds nailed on the kennel, or

wherever else those trophies of his skill are exhibited. It is a timid and

shy kind of hawk, and therefore very difficult to tame, never having an

appearance of contentment or confidence in its master when kept in

captivity.

Another beautiful little

hawk is common here in the winter, the merlin. This bird visits us about

October, and leaves us in the spring. Scarcely larger than a thrush, the

courageous little fellow glides with the rapidity of thought on blackbird

or field-fare, sometimes even on the partridges, and striking his game on

the back of the head, kills it at a single blow. The merlin is a very bold

bird, and seems afraid of nothing. I one day winged one as he was passing

over my head at a great height. The little fellow, small as he was, flung

himself on his back when I went to pick him up, and gave battle most

furiously, darting out his talons (which are as sharp and hard as needles)

at everything that approached him. We took him home, however, and I put

him into the walled garden, where he lived for more than a year. He very

soon became quite tame, and came on being called to receive his food,

which consisted of birds, mice, etc. So fearless was he, that he flew

instantly at the largest kind of sea-gull or crow that we gave him. When

hungry, and no other food was at hand, he would attend the gardener when

digging, and swallow the large earthworms as they were turned up. To my

great regret, we found the little bird lying dead under the tree in which

he usually roosted; and though I examined him carefully, I could not find

out the cause of his death.

Although all these small

hawks which frequent this country destroy a certain quantity of game,

their principal food consists of thrushes, blackbirds, and other small

birds. In the winter, when the greenfinches collect in large flocks on the

stubble fields, I have frequently seen the merlin or sparrowhawk suddenly

glide round the angle of some hedgerow or plantation, and taking up a bird

from the middle of the flock, carry it off almost before his presence is

observed by the rest of the greenfinches.

Sometimes two merlins hunt

together, and, as it were, course a lark, or even swallow, in the air, the

two hawks assisting each other in the most systematic manner. First one

hawk chases the unfortunate bird for a short time, while his companion

hovers quietly at hand; in a minute or so, the latter relieves his

fellow-hunter, who in his turn rests. In this way they soon tire out the

lark or swallow; and catching the poor bird in mid-air, one of the hawks

flies away with him, leaving his companion to hunt alone till his return

from feeding their young brood.

The hobby, a beautiful

little hawk, like a miniature peregrine falcon, is not very common here,

though I have occasionally killed it. This kind of hawk leaves us before

the winter. I have seen its nest in a fir or larch tree; but they seem to

be very rare here. A strong courageous bird, the hobby attacks and preys

on pigeons and partridges, though so much larger than himself.

Since the introduction of

English traps and keepers, all birds of prey are gradually decreasing in

this country, whilst blackbirds, thrushes, and other singing birds

increase most rapidly. In the highland districts of Moray, where a few

years back a blackbird or thrush was rather a rare bird, owing to the

skill and perseverance of gamekeepers and vermin-trappers in exterminating

their enemies, they now abound, devastating our fruit-gardens, but amply

repaying all the mischief they do by enlivening every glade and grove with

their joyous songs. This year (1846) the thrushes and blackbirds were in

full voice in January, owing to the mildness of the winter; and I knew of

a thrush who was sitting on eggs during the most severe storm of snow that

we have had the whole season.

|