|

ONE morning, I landed at

Lerwick. My destination was the far north of the island-some twenty-five

miles away-which I must reach ere nightfall. There was a talk of a half-way

house, and that was hopeful in case of accident. The walk was at once

depressing and interesting. It was depressing because of the almost

universal pall of peat resting on the landscape ; the ragged, marshlike

lakes, and the generally uninhabited look. Over long stretches, with the

same dark environment, I passed no one.

An old woman came from a

miserable hovelshe called it a "peerie," meaning a small house. Her "peerie"

cow, allied to the native longhorn, was grazing on the rough herbage of the

roadside. It was a scene Dante might have included in his Inferno. Yet she

was happy, as she led her sole companion back to their common home, where

they lived under one roof, and coughed together in the smoke that found its

way, so lazily, through a hole in the roof.

From the sheer walls of cut

peat, stuck out branches and trunks of trees, telling that the bare scene

had known better times. But that did not improve matters ; any more than a

tumbledown dwelling does a dreary outlook, or a stranded wreck the seashore.

Wearing on for afternoon, the thoughts wandered ahead to that half-way

house, which each turn of the road seemed to put so much further away. On

appearing, it but added to the desolation.

By the edge of one of a

string of marshy lochs, with a background of one of a series of dark peaty

hills, it was part of the scene-as depressing, as bare, as inhospitable. A

boy brought in a two-pound trout, which he had caught on a set line; it

looked dark and forbidding, as though cut out of peat. The lochs, I was

told, were full of such trout-a fact I afterwards found out for myself.

Over these hills the Shetland

ponies roam ; by these dark lochs they drink. They pass along the skyline;

they toss their manes; and with dripping lips vanish into the shadow of the

peat. No wonder if they are elfish in size, sometimes also in spirit. Other

than these was not much by the way. Parts seemed too bare to support life,

or make it worth living. Even a wild creature-that asks for so little-would

have given up the ghost from sheer ennui.

Previous attempts to

naturalize grouse had failed. Within the last two or three years, the

experiment has been repeated. The scene chosen was the drier upland

region-the highlands of Shetland-whither I was bound. In 1901, a hundred

brace was put down on the Lunnastig Hills, north of the mainland ; and a few

have found their way as far south as Lerwick. Last year a little mild

shooting was done. The gentleman mainly responsible for the experiment is

pleased with the appearances, so far as they have gone. A bad season will

undo much. A few might drag through to start over again, and so form a link

in a chain of disappointments.

With the benevolent view of

giving the crofter an occasional dinner of the strange creature-that, when

out peat cutting had sought his fellowship from the black forbidding moor,

or beat against his dim crusie-lighted window in the height of a Shetland

storm-the scheme is amiable. It might even be commended for the adoption of

other philanthropists. The want of fences as a preventative to poaching, is

felt to be a weakness. But fencing would hamper the free life which moulds

the pony. So would one of the most characteristic products of the island be

in danger of losing much of its wild grace. Altogether Shetland were better

let alone. Indeed only a very good reason can justify the forcing of

newcomers on the native fauna. There is always some disturbance of the

balance.

And, in the interests of this

doubtful experiment, the evils attending on grouse shooting in the south are

being imported. A gamekeeper has been engaged. Vermin are being shot. What

constitutes vermin is left to the aforesaid gamekeeper, who is given to

seeing it in everything, except the creature he is left to watch. Vermin has

not the same range as in the Highlands. The four-footed kind are mainly

absent. The falcons and hawks, which lend so much interest and charm to the

Shetland fauna, are in danger. In a new place, unhampered by evil

traditions, let a new era set in, a new and saner treatment be followed.

Then would the experiment not be barren, even if it failed. Let the invading

grouse take the ordinary risks. If it cannot hold its own against an enemy

infinitely less hurtful than the climate, let that be the test that it ought

not to be there. What is needed for survival under unfavourable

circumstances is exceeding robustness. If any agent can brace and select,

and so create a moorland fauna for the abundant heather of Shetland, that

agent is the falcon. Common sense would advise the importation of a few

falcons, if there were not enough.

Further efforts to enrich the

fauna, and make the northern isles more to resemble the Highlands, are being

made. The dark hills must in every detail become modern shooting moors. The

white hare is following on the grouse. It is now some time since it came to

Orkney. So very jealous is the proprietor of his possession, that he is said

to be killing out the interferers with its well-being and spread. To kill

the hawks for the sake of grouse is at least traditional : there is a

precedent. To kill hawks for the white hare is new-fangled. But a new broom

sweeps clean. In the hare is the comedy of the situation.

Shetlanders are turning their

eyes to the mountain hares-one asked through the newspaper where they could

be got. How very remote must be that man's dwelling? Why almost anywhere

north of the Tay. Many proprietors would be glad to get them taken away. The

man who is at all this trouble, and inquires anxiously how they are likely

to stand the journey, will be sure to watch over his pets. For the sake of a

few hares, which are as common as rabbits, the rare native fauna must

suffer. Should the craze spread, Shetland is not unlikely to pass through

the dark ages of the Highlands, from which it may emerge at some distant

date, miserably poorer.

The way through the dreary

environment was interesting, because of what was underfoot. The paving of

the Inferno is said to be better than the place itself. I am not disposed to

have much to do with stones, in a record of living forms-the matter is too

cold and dead. It is scarcely possible to pass unnoticed anything so very

striking.

Beginning with the Lerwick

sandstone as a base, the road-so far as I can now picture it, and I have

passed over more than once - was an object lesson in earth lore. It laid

bare the structure of the island, if not also of Scotland. I cannot recall,

anywhere else, quite so vivid a revelation.

From under the tilted

sandstone, lime cropped to the surface. The way was laid in lime. And by the

roadside, where in the south are whinstones, were piles of limestone waiting

for the hammer. Anon a stretch of road glinted with mica schist, another

glittered with gneiss ; still another was golden toned with broken-down

granite. The road glitters and glints and passes into gold before me. In the

stone-breaker's corner, appeared, in succession, piles of silver or golden

sheen.

It was a picture as well as a

revelation, this road of varied hue ; white or pink with sandstone, blue

with lime, silvery with mica or gneiss, golden with granite. A change on

some southern roads, so wearisome and headachy in their dusty grey. A

stonebreaker in Fife once told me to go a mile further on, and I would see

bonnie metal-that man had a soul in him. Straightway the whinstone changed

to porphyrite, the grey ceased, and the road was paved with pink. This

Shetland road was of still bonnier metal.

On the charming paving I had

loitered the day away. Nor was I quite out of Inferno, but only in another

part. There was a change, but scarcely for the better. The road entered on a

quaking bog, where was a trembling underfoot. Over this boggy land the sun

was setting. Though so mild the climate, the relation of day and night

approach to Arctic. The midsummer sun sets later than the early-bedding

natives. This is already a sleeping land in daylight.

Mist came, or crawled down.

The enemy is mist. A slight chill will weave it from the moisture-laden air.

The change from day temperature is often enough. There are two typical

summer evenings, when the moisture reveals its presence in the rainbow hues

of sunset, or a coloured haze scarce less lovely; and when it is grey or

black with mist. I learned to know all three. The first lesson was the mist.

The closed curtains deadened

sound, if sound there were, as well as veiled sight. Strange chattering

voices as of primeval men broke out close at hand; figures loomed large,

because undefined. I was in the midst of a family of tramps. They found me

lodging for the night ; it matters not where.

Such was the end of the

bright road that led through Inferno. The mist was the last phase. I issued

from it to know the Shetland I have since known and loved; a land sparkling

and alluring. I awoke to its teeming voes and flashing sea coasts.

The stillness had freshened

into wind ; the mist came down in slanting rain. A wild morning broke. I

looked out on the inland-stretching arms or tentacles of ocean. Twice a day,

tides from the Atlantic or North Sea moved on the face of the waters ; it

was infinitely fresher than the black lakes-life for death. Bare heights of

glittering schist or red granite rose clear out of the peat.

By the side of one of these

northern voes I settled down, with rippling canvas for walls and a roof. It

was pleasant to rock out at the flow of the tide, and look over the side of

the boat. So amazing was the fecundity of the Shetland waters, especially

those that branched, as ours did, from the west. Atlantic tides seemed in

the throes of a mighty birth. Life teemed, rolled over life, and disappeared

in the mass, to rise again wherever there was room.

And how great the forms were;

what circles the jellyfishes made. Aurelia, with its four purple crescents;

and Cyanea, with long floating streamers. The colours-the purples, the

blues, the browns-in curves, in masses, in lines, against the neutral shades

of the umbrella or water, sated, as does the passage of an army.

The lesser medusae - over

which these great forms rolled away inland - when one could get the net

through to bring them to light, were as bewildering in abundance and beauty.

One form I remember. It is called after a Swedish naturalist. So minute that

it was only revealed to the naked eye through a point of orange or crimson ;

but so great in number as to form a solid mass in the net. Under the

microscope these spots were found encased in exquisite bells.

What sunsets were there. The

rainbow broken and scattered on the clouds, the diffused glory of haze

spreading a flush of nameless hue over voe and land and croft. The memory

comes back on a sigh; the flush lingers on the spirit.

Less sensational, but

stranger and more moving, was that which came after; the light that kept

fading but never failed; the scene that kept vanishing but only softened its

outlines: the lingering northern twilight. The great trout sailed up from

the sea with the jellyfish; they leapt around the boat in the evening light

; they played by the channels of hybrid lochs, which are landlocked at the

ebb, waiting to enter on the flow.

Birds twittered round the

tent, where, with a lingering of our southern habits, we were vainly trying

to find a softer place on our heather couch, and get to sleep. One must be a

Shetlander to sleep in a northern twilight, just as one must be a Shetlander

to sit out the long winter dark to the dim crusie flame. One can do little

but doze in the mystic half-light. I saw the shallowness of the sleep, as,

in my wakeful moments, I looked on the face of my companion.

Wrens met us, especially

where were dry stone dykes, near the scant clearings or dwellings of man.

And with that social habit of theirs -which can find but little exercise

where so few are abroad-went some distance on our way. Nor is the

pleasantness of fellowship confined to them. I imagine the Shetlander in his

lonely walk, is not unwilling to have the attendant bird. The place itself

extends the bonds of sympathy. I recall a tramp along wild cliffs to a

distant voe with a friendly bird. They seemed much larger than our wrens and

less dusky shaded. A new species has been made out of differences no

greater. Witness the St. Kilda wren. The two are not unlike. Island life and

similar conditions may have modified both in the same direction. What little

dissimilarity there is may be accounted for by the unlikeness of the two

islands. Perhaps I ought to have kept silent, lest it be needful to guard

this wren also by a special Act of Parliament.

On the shore, the Arctic tern

makes a nest of seaweed. Often the eggs are olive coloured like the nest. As

the hooded from the carrion crow, the Arctic tern is distinguished by its

range. It is a northern variety of the common tern, nothing more. Where they

occupy the same nesting area they probably cross. Perhaps it would be closer

to the truth to say that one grades into the other. In the latitude of the

Forth, it is hard to tell whether there be Arctic terns or no. While one

naturalist asserts that they abound, another is quite as sure that they are

absent. Both may be right, and the truth somewhere between them, as it is

between most disputants. It may be a transition area. Eggs are found of all

intermediate shades and sizes. I have watched a wiseacre, after robbing the

nests, lay them out in two separate piles, when one pile would have done for

both.

The cliffs, and the water

which washes round their base, teem, as do the voes. The sea-air flashes

with wings; the surface of the sea is broken with the diving. On the cliffs,

forms jostle for place. What abounding life is there! Where the kittiwakes

can scarce find room on the rock ledges for their dainty young, with the

black half-ring round their neck; where puffins bob; and cormorants sit,

with the still, sullen gravity of pieces of rock. Any softening of the rude

majesty of coast into shelly strand is a haunt of countless ringed plovers.

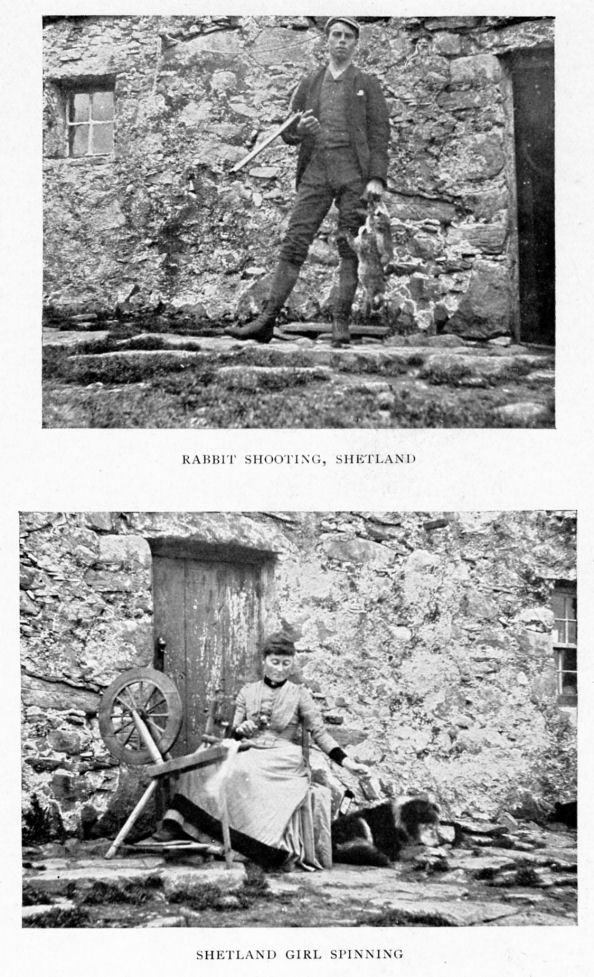

I have a photograph of one of

our number bringing in a pair of rabbits he had just shot for dinner. Older

denizens than the white hare, their date is unknown. On a sea-isolated rock,

little more than an acre in extent, and scantily grass covered, I have seen

them squirming about in dozens. Silent children of the solitudes were they,

against the lifeless stone and screaming seabirds.

Another of our number shot a

stoat on its way into a rabbit-hole. I have stretched myself beside one of

these island warrens, with the sea breeze fanning one or other cheek, and

the sound of water in the ear. The play was free, as of creatures little

familiar with man. I was not their enemy. The stoat was never far away, nor

long to wait for.

Here is a clear field. With

abundance of stoats is superabundance of rabbits. And the lesson comes

clearly out, that in the same natural way the balance would be preserved

elsewhere. Between the new gamekeeper for the score or two of grouse, and

the stoat which overlooks these Shetland warrens, there can be no doubt as

to which does the duty better.

Apart from the rabbit and the

stoat, and probably the otter, the mammals are made up of the half-wild

ponies, the long-horned cattle, and the small native sheep. I mean the land

mammals. On the coast rocks seals bask, and off the shore several species of

the whale family blow.

|