|

NOT much of the chalk is left

in Scotland. An occasional flint rolling in upon the shore seems to hint at

a possible deposit under water off Aberdeen. That and a few patches on the

west coast are all. With the chalk my story begins. A somewhat dim phase of

geologic time, it was pregnant with great issues in the evolution of life.

Archaic creatures enter, to appear on the hither side as forms with which we

are more familiar.

In the interval the mammals

received their initial development. Among the rest the ungulates may be said

to have come into being. In numbers they crowded forth. In vast flocks and

herds they scattered over the plains and marshes of a new world. If not

exactly as we know them, still sufficiently near to be easily recognized.

Their habits were as now. Their share was every green thing, the grass that

grows for the cattle.

That they are hoofed animals

is diagnostic enough, but not quite in balance. We give our names at

haphazard, or without reference to other names. We might as well call the

cats clawed animals. The cats and the cattle-excuse the slight alliteration

if not something worse-run in couples, and should be named along the same

lines. There is a history and brief chronicle in well-chosen names where one

leads on to another. If we called them grass-eaters quite a world of

obscurity would be cleared up.

For we straightway come upon

the flesh-eaters. Indeed the two were twin-born from the same generalized

form. There is a natural fitness in the arrangement, a sequence which we

should most assuredly observe. In two groups thus linked, to call one by the

teeth and the other by the hoofs is the act of blunderers. The first group

eat grass, and so make flesh, therefore graminivores; the second group eat

the flesh thus made, so carnivores.

No other two forms have a

like significance. No others are so linked in bonds that are indissoluble.

These were the two great protagonists. Like other twins, they straightway

fell out. There is a sense in which ungulate is not unfitting. Ingenuity can

always find a meaning in the blunders of the name-givers, even when it is

not the most obvious one. It was a trial of speed against strength; of hoof

with teeth. The tragedy of the world began then. The cry of fear and pain

seems to reach us across the aeons. These things had been before, but in

dimmer and more uncouth forms the Calibans of creation - which do not touch

our sympathies.

As in other matters, the past

may be re-created out of the present. A few incidents, once common where we

stand, are still enacted elsewhere. In South Africa, for instance, where

herds of wary grass-feeders out on the plain are ready to start on the first

alarm, while silent carnivores-the lion and the leopard-prowl round the

outskirts, or stalk with a certain deadly skill. This discipline has been at

the forming of our tame cattle. It helps to explain a hundred little ways

they have got, taken by the dull herd as a matter of course, but really

dating back beyond Guelph and Plantagenet.

We have changed all that. And

here the larger outlines of the persecution are seen, the beginning of the

policy which has kept on in lesser circles, and whose working is not stayed.

The psychology of the movement is also made plain. The motives which are

hidden under so many flattering aliases.

In a sense we are carnivores,

though, conveniently for ourselves, we combine the tastes of both. In this

we brook no rival, nor are we delicate in our methods of getting rid of

those which exist. Our nomenclature here also is defective, by reason of

weakness. Ours is the good old rule, the simple plan that they may take who

have the power. We are an aggressive race. We have really no other right to

do anything of the kind, no right but might. No right but the weapons we

have been able to make, and the excuses we have been able to frame. We do a

thing and then include it in a decalogue, shift the responsibility

elsewhere. We may assume a virtue, but certainly we have it not. Fine names

butter no parsnips, nor do they alter facts. Nor do the commandments satisfy

a conscience that is not moulded to order. I have heard the whole matter

condensed into the convenient formula that animals have no souls. This is

clearly a case of swollen head. An unvarnished statement of the relation is

nearer the truth.

We came between the

carnivores and their dinner, and having slain the slayer sat down to the

repast, upon which we said grace. We killed them out because they persisted

in using their canines, and then proceeded to use our own. Before eating we

lit a fire to show how cooking alters the moral complexion of actions. We

rung down the curtain that the tragedy might be enacted behind; deadened the

cry of pain and fear that it might not reach over-sensitive ears.

The sentinel, the false

alarm, the short fierce combat - which were at least picturesque and

impressive, and half redeemed the ruder parts belong to an heroic age. We

have no belief in heroics. We seek no arena for our deeds, which might lend

them of its own greatness. We act secretly in dark, narrow places. Were we

dealing with men we might be said to assassinate.

Even as I write a little

group of cattle - the one nearest an innocent-looking brute, with a great

disc of white round the eye-are passing the window on their way from the

pasture to the town. Behind is a lout, with no special marks of person to

commend him as anything superior to his charge. Perhaps the chief advantage

is the stick, the original of weapons, the crudest symbol of man's

sovereignty.

In his reminiscences, Dean

Ramsay tells of a guest in a Scots house who was late in coming down to

dinner. Donald, the manservant,. sent to find out the reason of the delay,

surprised him using an instrument with which he, Donald, was unfamiliar-a

tooth-brush, to wit. Still the guest delayed. "But, Donald," said the

master, "are you sure you made the gentleman understand?" "Understand," was

the retort, "I'se warrant he understands. He's sharpin' his teeth." While

the herd was on the way, the town was sharpin' its teeth.

So it is. The great

carnivores are extinct, killed by our hands. The grass-eaters are preserved.

Not because we love them, save in a very carnal way. The warfare goes on,

only in a less interesting mode, and with a change of one of the combatants.

We hide it from others by a sort of common understanding ; and from

ourselves because we would rather feel virtuous.

While we settle our

differences with our fellow carnivores, the ungulates are not spared. They

can have no opinion to offer in favour of the change. It can make very

little difference to them who eats, so long as they are eaten. An Englishman

dearly loves his dinner. A Scotsman does not like to be without. It is our

infirmity. We all eat. There is no harm. We were made that way. We should

all be less open to criticism if we did not strike an attitude ; and

compound for the sins of our mouth by the length of our face. I n the

rough-and-tumble past, we have somehow come out at the top. Had we been

under, we might have seen from another point of view. The advantage of a

little imagination is, that it helps us to see ourselves from the outside.

One, well known in London,

got into a bypath in Scotland. When wending his way up a Highland glen he

chanced to meet strange cattle -long-horned, shaggy-coated, some dun-coloured,

like the evening light along the slope of the hills, some wan as a stormy

gleam on the loch. They were such as Rosa Bonheur would have delighted to

paint. To her, they would have been welcome, and looked friendly. In her,

they would have awakened only admiration for their strength and

picturesqueness, and a sense how well they became the rude path, and the

rough moorland, stretching away to the misty hill tops. Now Rosa Bonheur

would never have thought of painting the visitor as a fine animal-which

probably he was not-nor as anything else. Scant appeal would he have made to

her artistic sense. In indifference or contempt she would have turned away

to stroke the dun or wan shoulders.

All is in the soul, or want

of soul, that looks. In the new-comer, these children of the wilds excited

only fear and trembling, and a sense of danger to life and limb. The long

horns and rough coat, which brought the glow to the wandering artist's face,

were the panoply of a ferocious nature ; the eyes glistening through their

shaggy fringes with a wild and alluring light meant mischief, of which he

was, perhaps, the immediate object. Barren of the artistic love which

casteth out fear, he was craven before these fearless mountaineers. On a

fenceless moor, they had all the advantage.

What means he took to secure

his safety is not on record ; but, on his return home, he wrote to a

magazine, protesting against allowing wild beasts to wander in the possible

track of innocents abroad. Think of the loss to society if one of them were

impaled. Possibly they met under happier circumstances, for the tourist.

Highland cattle do sometimes leave their native wilds to visit Smithfield

Market. With his legs under his own mahogany, and his napkin duly spread

over his waistcoat, man would be master of the situation.

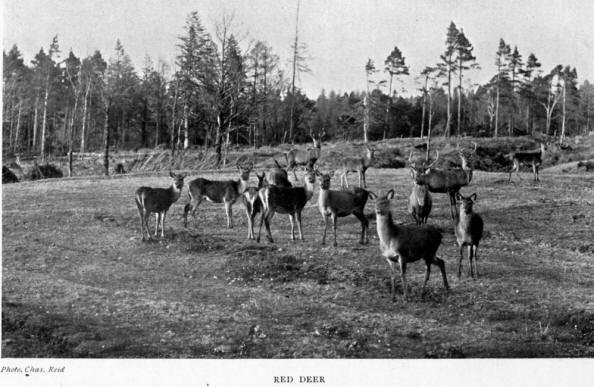

In the Highlands are other

ungulates than the cattle. Sooner or later, in its windings among the hills,

the glen would eddy into some stern culde-sac, misnamed a forest. The deer

pent in there are no longer simple-horned, but antlered. Less formidable

than picturesque, the appeal of the head is aesthetic. Little tines or

branchlets to the number, it may be, of a score, shoot out here and there.

In woodland animals, these might serve for concealment, the tines being lost

amid the tracery of the trees. That they are weapons of offence is witnessed

by the deadly combats among the stags, while the hinds stand by with the

cruelty of gentleness. Moods there are in which the approach of man is made

at his own risk.

Morning and evening, when the

shadows fall eastward or westward, they come from the high grounds, to feed

on the long and juicy grasses by the ash-strip or the burn. Had the fresh or

tired tourist turned in that way, he might have seen no cause for alarm.

Deer are, in the main, shy, and when disturbed drift away like shadows. A

fleeting vision and they are lost, and the glen is empty, save of the

self-created fears of a great solitude.

With infinitely more of the

wild animal about them, deer help us to picture the old relations. They have

all the resources, all the wariness, all the pristine freshness of sense, of

days before the captivity. Scent is exquisite, sight keen. They hold a

wireless communication with an enemy coming down the wind, detect a distant

movement of the heather tuft which conceals danger. Fleet as the breeze

which brings the scent, is the speed of their vanishing. The hoof has the

old mission, to bear to some sanctuary, beyond the reach of pursuit.

Little happens in the herds

of South Africa that does not also happen in these glens, nothing essential.

On the veldt, both sides are serious, that is, perhaps, the only difference.

With the deer of the glen it is serious enough. It is all as when the wolf

came slinking up, under the shelter of the perched boulder, or, with his

long swinging gallop, followed on their track.

The wolf is no more. We

resented his interference, and wished the deer for ourselves. We killed him,

and took his place. We did not turn the quarry, which as successful rievers

we had thus acquired, within the fences, as we do cattle, to fatten for our

use. Rather we took a double toll. We sought to preserve the picturesque,

the heroic element. We could catch first and eat afterward. We would kill,

not behind doors, but in the open, and under the sky.

Our wit was pitted against

the wit of the quarry. We met wile with wile—ambushed, crawled, sought the

alliance of the wind, of the sympathetic shading of the ground until we came

within distance. We would even choose our body-covering to aid in

concealment, as the hair or fur is toned by nature. We would masquerade as

wild animals, as carnivores over against the feeding ungulates. There is

nothing original in all this. It is a case of reversion, a calling of the

underlying wild instincts to the surface.

An element of fair play

brightens the series of episodes. We give the deer a chance for its life,

which is more than we do for the cattle, only we see that it does not get

away, as it might do in a truly wild scene, and from its natural enemies.

This interval between the grazing and the gralloching, between appetite and

dinner, we call sport. It is a pretty name for a certain usurpation of the

methods of the animals we have first disinherited. As in other cases, we

adopt without acknowledgment. We deny the name to the manoeuvres we copy. We

think that sport is the prerogative of man, who has a soul. It is an

afterthought. What matter? They are alike. The same wild instincts are at

work, with the same pleasure in their exercise.

I have no quarrel with this

copy. I like heroics, even when they are not quite sincere. A very little

acquaintance with life tells us that it would be a poor show in the absence

of a little illusion. Only an enemy of his race would do away with the

staging-what the Frenchman calls the music. Sport has all the charm claimed

for it. The interlude makes all the difference between the death of the deer

on the heather at the end of a long stalk and the fate of cattle. I have

nothing to say in favour of driving.

Thus have we got, not only

the eating, but also the fun to ourselves, by the simple process of killing

out all that asked a share. We have put out myriad lights that every path,

save our own, should be dark. We have a monopoly of the pain and the

gladness of the earth. The pain is to others. The gladness may not be all it

seems. And, as we have had the making of the decalogues, we have found it

easy to prove that this was all right.

These are the days of small

things. Our activities are confined to the inner circles. We are busy among

the lesser carnivores, which in the absence of any small ungulates find

grass-eating prey of another kind. We step in between the weasel or the cat

and the rabbit. We are concerned about the warfare of the birds, and rescue

the grouse from the falcon. We want the game for ourselves.

We want also the savage

pleasure of the pursuit, or the kill. In so far only as we copy, has sport

any meaning. The methods we have added are spurious. It is we who are not

sportsmen. In the very act of removing the natural enemies we make the game

more helpless, killing easier, and sport impossible.

This may be civilization, but

it has a marvellous look of another thing. It seems somewhat of a grim

farce. It is well to keep the view narrowed, and the parson at our elbow. I

do not know how it would stand a little cross-questioning, or fare at a

great assize. |