|

HAVE determined to keep my

hands free from extermination. The marten and wild cat are not banished from

the shaggy woods and rough braes of Sonnachan and Barbea." So the olden

sportsman, who rented his first moor as far back as 1822, entered the strong

protest of personal example against the ways of the new lessees who were

invading the Highlands.

One against a crowd of

exterminators, with his back against a rock on behalf of the native wild

creatures. And willing to be treated as an eccentric for his whimsical

forbearance. This man died, and no one filled his place. Those who laughed

at him had it all their own way, blighted the hills-for which, not being to

the manner born, they had no natural or traditional care-and, generally, had

their money's worth.

Needs but to look around to

see the type - the man of commercial instincts, who has rented a moor late

in life, and takes thither the maxims of the counting-house. His son, who

practises from behind mock butts, at grouse set free from traps-a fitting

school for those without sporting instincts, with no innate love of hill

scenes or wild life, in whose hands money alone has placed a gun to work

mischief. And, having knocked over the needful percentage to qualify for

serious work, the enfant terrine shifts behind a real butt, and shows his

skill on the birds, driven up to him by an army of hirelings.

Under such auspices, whose

blight, unfortunately, fell on those who ought to have known better, the

killing waxed in virulence. Each creature not a grouse was a bete noir.

Mercy was neither shown nor asked. Not asked, because wild creatures do not

whine, but take the billet within the bullet, and die, free and

bold-spirited, as they have lived. And the murnful conclusion seems to be,

that the work was done only too well.

A correspondent remembers a

marten at Barcaldine, in Argyllshire, being thrown on the hall table in

1865-6. That is a long time ago. What matters fifty, forty, or thirty years

? Certainly nothing to the marten. The vital part was the killing out, the

throwing on the hall table of what was so much more interesting than that

for whose sake it was killed. This feeling seems to have been present in the

writer, who personally inspected with boyish curiosity something out of the

common. It was one less. Other hall tables had the same burden. And so from

district to district was the marten wiped out.

In 1883 one was seen in

Faskally Wood. Where is it now? Wandering, doubtless, in denser shades,

where, by a law of compensation found in most things, it may be hunting its

earthly hunters, or waiting for such as are still busy here. Are any abroad

in Faskally Wood to-day? If so, is it intended that they shall remain ? Of

creatures-once found anywhere -to surprise one in Barcaldine, and another in

Faskally, at an interval of eighteen years, only intensifies the desolation

over the rest of the land and the barbarity of the persecution. No vandalism

is ever so thorough that it leaves no ruin, and the ruin certainly does not

lessen the sense of the vandalism. Is it not needed to aid the imagination ?

One would rather not rake up instances of how many the

shooters-notwithstanding their training with the gun-have missed, to modify

the indictment.

At Knoydart, in 1898, a

keeper had six skins, taken from animals trapped during the preceding

winter. " But being aware," says a distinguished naturalist to whom they

were shown, " how surely the progeny of the homely tabby reverts to the

native type in size, in the shape of the tail, in the colour and quality of

the fur, I suspended judgment." Is it right to talk of reverting to the wild

type unless the wild strain is already present? Assuming it would thrive,

wholly undetached from a house, the tame cat might at a very long interval,

and by a process of selection, acquire a thicker fur and a certain

protective shading. That is not reversion.

Crossing is a much shorter

process. A keen observer says that the tame cats most given to wandering are

those which resemble the wild ones in colour. A very different thing from

going forth and straightway changing the hue. And may hint at some of the

strange weaving, in the web and woof of wild and tame. Not unlikely the

roving house-cat owes to an older rover the colour which it is now taking

back to the domain of one of its ancestors.

The following winter Knoydart

produced a brace of heads. On the evidence of certain bones of the skull, an

expert in South Kensington pronounced the bearer, when in life, as

indistinguishable from pure Felis catus. The opinion is hasty though,

doubtless, orthodox. The immense house-cat, seen by St. John, showed certain

peculiarities of its wild father's race, not only in the shortness and

roughness of the tail, but also in the size and shape of the head-in other

words, the bones of the skull.

The expert, therefore, might

be quite right and at the same time quite wrong, orthodox without being

true. An expert may narrow his horizon to make sure of his facts, and keep

to one side in case the other should contradict him. He may know the points

of a wild cat without being familiar with the conditions of wild life in

Scotland, by much the more important factor. Had the Sutherlandshire cat

been sent he would have called it a wild cat, if only it had been concealed

that it came out of a keeper's lodge. No one, not even he of South

Kensington, will assert that' a cross may not have its father's head as well

as its father's tail. The reason why tail and head alike were in northern

croft and lodge is just this curious juxtaposition of allied species. If now

they are found in the wilds, it is because the persecution has given a

predominance to the domestic strain, which has not been persecuted. I n this

is nothing strange when we know all the facts.

It may be assumed that these

six Knoydart skins were not of tame cats, and it is fairly certain that the

two skulls tell of a wild ancestry. The point at issue is whether the

wearers, when in life, were more likely to be true or crosses. One of the

unhappy outcomes of the persecution is, that the most liberal of landlords

has not the satisfaction of knowing what he is harbouring.

A timorous correspondent

fears that to throw doubt on the genuineness is to lessen the interest, and

so endanger those that are left. No good ever came of feigning blindness to

facts, nor cure from physician who persisted in seeing health where was

none. I did not make the situation. The peculiar mischief wrought, and the

vague uncertainty being left behind, are none of my doing. My wish is to

point out the double agency of destruction which persecution lets loose-the

blight of crossing on the doomed species. To rejoice because a few wild cats

- granting them true - are found here and there amid a legion of tame cats

is to live in a fool's paradise. Either something like the old predominance

will have to be restored, or they will have to go out at the one door or the

other. I deserve better than blame, even from the optimist, whose natural

history may be getting rather musty, for providing him with fresh matter for

curious speculation.

By all means give space and

liberty to breed and gather. If one man has resolved to keep his hands from

killing, to make the cat and the marten free to the rough woods of Knoydart,

nor grudge them their share, I cry "Bravo!" No harm will come from the

charge of whimsical forbearance on the lips of those who are not like

minded, nor worth minding, save for the mischief they do. There may be still

a chance of some of the old strain. Even if not altogether wild, they are

the nearest we can now get, and that is something. Under wild conditions,

the bent will be toward the wilder ancestry. A modified persecution that is

only short of extinction is vain. The other agent will take the matter up,

and bring it to an issue. Satan will be found in the person of tabby purring

on the doorstep.

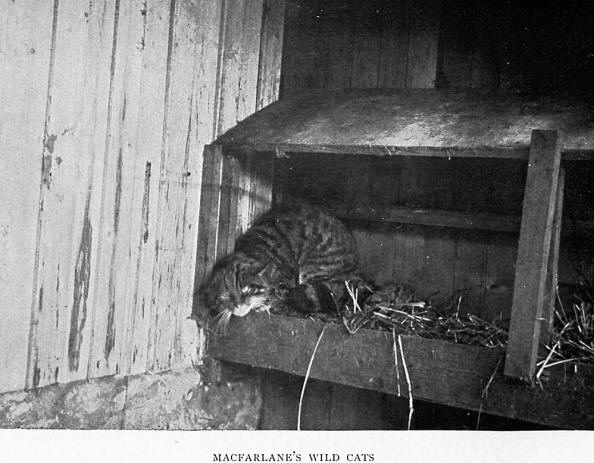

Two cats were captured near

Invergarry, in Inverness-shire, and now form part of an interesting little

live collection at Kingussie, the capital of Badenock. Fierce and strong

enough, they broke through the wire investment, killed so many rare fowl as

to wreck the collection, and made their escape. Traps were set. With their

usual fearlessness, they took the bait, and were brought back to

confinement.

As a domestic cat cornered by

a terrier, so they growl and spit, and flash a fierce light on all who

approach. Any cat that had led a wild life, and been brought in when grown

up, would act in this way. Man is the terrier dog. On an authority, which

one strongly hesitates to gainsay, these are said to be genuine wild cats.

I certainly have no desire to

play the sceptic. Were my interest in the wild life of the land not so great

I would not write. I am inclined to look on these captives with a friendly

eye, half ready to be deceived. Only one or two things occur to me. Crosses

might present all the appearances of these cats. It is the uncertainty that

troubles. The appeal is not conclusive. Wild cats should be in a strong body

if they are to remain pure. And where is the strength to be found. Probably,

too, domestic cats would have to be weak; and they are strong.

Manifestly these cats are

rarities, otherwise why make so much of them? If there are many more,

methinks "the lady doth protest too much." Whence arose the two in the empty

woodland, where only the ghosts of their forefathers walk? When a wild

animal in the centre of its ancestral domain is kept captive, the case is

hopeless. If these are genuine wild cats—where is so much obscurity, the

only two known in the land—why not turn them out? Is there no bid for them?

Can no landlord be found who will give them the run of his place? If not,

why talk of the wild cats of Scotland on the strength of two barred in a

cage?

If such considerations do not

appeal to those who are already convinced, I can only quote a testimony

which, in the view of the man in the street, will outweigh that of an

expert. I am asked to account for six skins, two skulls, and two live

animals, together with the assertion of many more where these came from.

Writing, some fifty years ago, when the strain was still strong in the land,

John Colquhoun says :— "I have spent a great part of my life in the most

mountainous districts of Scotland, where killing vermin formed the

gamekeeper’s principal business, and often my own recreation. I have never

seen more than five or six genuine wild cats. I have seen no less than

thirty naturalized wild cats, trapped in a year on a single preserve; some

of them might have been mistaken for the true breed. They were, in fact, a

cross between the wild and the tame cat."

Six wild cats seen all over

Scotland, in a lifetime, against thirty crosses in a single forest in one

year ! What chance that the wild cat survives. To which group are those said

to be abroad in Knoydart and other woods likely to belong?

Since the days of such scant

gleanings, fifty years have done their utmost to make a clean sweep. It is

no fault of the persecutors that any have escaped through the hairs of the

brush. Nor is there any very general abatement in this relentless work. The

whimsical forbearance of some individual proprietor, whose authority ends

with his fence, is interesting rather than important. Impotent then, it is

no more potent now. Whim and generosity, charming as they may be, are not

lasting, and, while they last, are very much on the surface. They are not

exactly what is wanted.

I hold no brief for these two

creatures nor plead for special treatment. The wild life of the land must

stand or fall together. Other mammals -only second, if at all inferior, in

their natural claims-have suffered. Trap and gun have been busy on them

also. If they are not nearer the end, if some are still dominant forms, it

is not through any forbearance, but that they have a genius for looking

after themselves.

Among birds the slaughter has

been great, the victims the noblest, the motive a few more grouse. The

following are of those denied the right of existence, save in the woods and

wilds over which Colquhoun had control. The golden eagle built in Glenlass,

so did several peregrines on the, wilder cliffs.

In the same pine-wood the

merlin was constantly flushed. One can scarcely credit the ignorance which

would slay a falcon so tiny, charming, and high-spirited, which robs no

nests, kills on the wing, and lives mainly on titlarks. Nor the absence of

fineness in him, who had no care for the lady's hawk-when outdoor life had

elements of charm and picturesqueness - which has fallen on evil days.

Sport, like everything else, is bare when it has no history, no regard for

living relics, no sense of backward perspective, no trace of old-world

gallantry. For the sake of her sister who loved the merlin, woman should

take it under her charge. It is hers to shorten the reign of ignorance and

prevent the doing of dark deeds. It would not be too much to ask for the

life of one bird ; and the merlin might repay her the debt. A merlin on a

lady's wrist, even in these prosaic days, might still be worth the painter's

brush. In the absence of gentle patronage, the merlin, like the peregrine,

will continue to owe its existence to its own resourcefulness.

"I have myself in one season

seen three nests of that sylvan ornament-the kite." In other woods than

Glenlass was the same happy abundance. One would search in vain for the

wilds where were three nests, and with scant hope over many wilds for even

one. It nests but in the memory that goes furthest back, or in the tale told

of olden days. From the worn seat on the village green of an evening, the

peasant might watch the slow wheel on motionless pinion so high that it

seemed scarce larger than the lark. It did no harm; but ignorance invents.

One never sees, seldom hears of the kite. Nowhere is it more than extremely

rare. No longer does it appear on the gamekeeper's gallows-like row of

examples; so effectively was the work done by those who went before. As the

eagle, so is the kite, a ground feeder, a greedy bird to boot, taking

readily whatever is laid down. Its capture is ridiculously easy, and within

the compass of the heaviest-witted trapper.

In certain districts a

somewhat belated sentiment now protects the golden eagle. Favouritism is

always offensive, and we forget to thank those who go on killing elsewhere.

That the eagle should be allowed to poise in the heavens by special

permission of the proprietor of the soil may be very nice, though it savours

of the largesse of the parvenu. But it is correspondingly ugly that other

birds should be denied a like privilege. It is one of the tricks played by

"man, proud man, dressed in a little brief authority."

So men blighted this new

playground in a rather sombre world, and having found a pleasant plaything

therein, proceeded to kill out all that made it pleasant. Of the living

forms, many of them strikingly beautiful, all intensely interesting, they

preserved but one. It is as though an Alpine were chosen out from the

glorious Alpines of our hills, and all the others were rooted up, lest they

interfered with its spread. This is not a matter for curious naturalists,

with their mild enthusiasm and inconsistent ways ; who may be pushed aside.

I can recall a student in

Edinburgh, son of a Highland chief, who boasted, rightly or wrongly, that he

alone in the university was privileged to wear an eagle's plume. It were

another of life's little ironies, if over the ancestral moor the eagle were

slaughtered. One sometimes wonders if those whose pride it is to be known by

the name of the cat grudge it a share of the spoil, and lease the rough

woods and braes to its destroyer. Hear the cry of outraged sentiment: "Is

there one mountain-born son of Alp who does not agree with me in preferring

our unspoiled glens, our wild game, and our national distinctions?"

Highlanders may have

forgotten all that made them and theirs picturesque and uncommon, and be

contented that once vital signs, which brought the proud curl to the lip,

should be empty of meaning. The lust of mammon has entered them. Others may

be interested if they are not. I should like that the whole matter be placed

before the public mind, and commended to a national sentiment. There is so

much that seems out of joint, and would not be, if people saw and felt

aright.

Notoriously proud of country,

a Scotsman should pay heed when all that touches the imagination and warms

the heart is being destroyed. In the scale of being, the heather might go,

and the Alpines might go before the wild creatures. So surely as they go,

the sentiment of country will wane along with them, and all our vapourings

will be but sound and fury, signifying nothing. It seems a small thing to

sell our cats and our weasels, our eagles and our falcons for gold. It is

bigger and more far-reaching than it looks.

A national might be

strengthened and, if need be, replaced by an imperial sentiment. If men at

home do not care, perhaps there is a more generous soul in those who have

gone away. I sometimes think, if they only knew how the wilds are being

blighted and the wild creatures slaughtered, so that the land is becoming

common as other lands, a voice would come across the water to help us. As

much sport as you like, but no murder. Let the years of the persecution

cease.

The greater Scotland is now

elsewhere - New Zealand, Australia, Canada, even the United States. Men who

emigrate go over to the majority. No one is so much a patriot as he who has

left his native land behind, nor so longs to find things as they were. If

the years of captivity linger, so much more desirable does the vision

become, till the heart aches for desire. Less intense, but not less

pathetic, and wholehearted his allegiance than that which found utterance

long ago: "If I forget thee, oh Jerusalem, may my right hand forget her

cunning." |