|

"I PRESERVE the golden eagle,

but shoot the peregrine." So, on 30th April, 1893, wrote the late Duke of

Argyll, concerning the two noblest forms of winged life. From an enlightened

proprietor, a humane man, and one profoundly interested in wild creatures,

this represented rather more than the sentiment of the time. The average

position is tersely put in the words of another correspondent. "We are

better off without the one and I do not see that the other is of any use."

There were those, not enlightened nor humane, who cared for neither falcon

nor eagle—perhaps, could scarcely distinguish one from the other and shot

both.

Intelligence selects;

ignorance kills. Self-interest rules throughout, with a milder or ruder

sway, hindering the action of an awakening aesthetic sense even in the most

tolerant. Some have an eye a little more discriminating than that of a

gamekeeper, which is no more than might reasonably be expected. Many have

not. In all the gamekeeper is represented. Where are deer forests are

occasional depredations, especially when the demands of the aerie are

insatiable.

From some lofty perch, the

eagle watches where the calf is hidden for the day. With a quick, feminine

instinct the hind-ere she turns the bend of the hill to join the herd-looks

back. And her heart stands still, because of that double speck in the air.

The eagle ascends dragging something aloft, as though bearing a second

Ganymede. It opens its claws. A quivering mass falls through the air ; and

so it kills the calf. With a low whimper, the hind speeds back -too late.

Such tragedies are in the wilds; such intense moments and breathless

incidents. Others see, and are wroth that a royal head has gone. On the

Argyll estates is no deer forest.

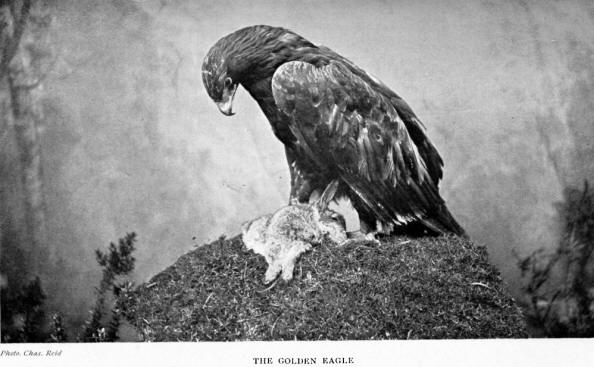

For the rest of the year, and

even in times of stress, the eagle prefers a mountain hare. It is not quite

so heavy to lift, and may be carried to some convenient perch, far from the

reach of disturbance. Fur is the favourite food for feather. Where are

plenty of hares, other forms of life are fairly safe. In deer forests, the

loss is inconsiderable. With a tendency to over-increase so that an annual

slaughter of the hinds takes place each December-two or three calves can

scarcely be missed.

Perhaps Argyllshire is not a

sporting county of the first order; not as Perthshire, for instance, nor

parts of Aberdeen down Braemar way. In common with all the west country, it

suffers from the blight of damp. The west winds trail their dripping fringes

over the hill slopes, thus sifting themselves of their moisture, till they

become the dry mountain breezes of the central Grampians. There are moors

with grouse large if few. And a golden eagle will pick up a grouse.

Still an eye with the light

of reason in it might see that this is not serious. And it is quite

conceivable that the intelligent owner of a moor might look on with

tolerance. The depredations of a pair do not greatly lessen the August bag.

Some have found the blue hare a greater enemy of sport than they, and

acknowledged the services in its removal. To spare the golden eagle over the

purple heather, and against the speedwell blue of the sky, is to borrow from

nature a spark of beauty at very little expense. To some that may not mean

much; but it is so. When it flops down on a grouse, it may be doing a

benefit. It is a messenger of nature. And, in a certain lofty way,-perhaps

outside ordinary reckoning, but which I shall try to make good, a servant of

the lessee.

Who is not charmed with the

rich dark plumage of the red grouse, or would have it altered ? Is it not

part of the glamour and the spell? It is autumny - of the heather when it

blooms. It is moorland and hill incarnate. It excites ever so fresh emotions

- calls up ever so delightful visions - leaves an unfading glow on the

spirit. The nearest relative is the willow grouse, of more arctic climes.

The cry is much the same; the eggs are indistinguishable. In one thing do

they differ. The willow grouse turns white in winter, and at all times is

paler hued. Charming and sympathetic as the plumage is, in the natural

haunts of the bird, here it would be out of place, and fatal. So that when

the bird came to Britain it changed into the red grouse. A tendency to

reversion is checked, and the hues are kept toned to the sober mountain

slopes.

Feathers with their varied

and exquisite touches -so rich at the shooting time when most seen - we owe

to selective agents. They are the largesse of an enemy of the individual,

and a friend of the cult.

On the scant wages of a few

birds, to vary the diet, the work goes on ceaselessly, and with such

charming results. August by August, grouse appear as they were,

indistinguishable from the background, in the delightful sympathy of toning.

Unaided, the background could not so tone them to its hues, take them to

itself. Of selective agents the golden eagle is one.

With head curved, he seems a

speck. More than one crouching covey baffles even his keen eye; so perfectly

has the work been done. Even the low flight from place to place is lost,

against a background which takes its living creatures in charge and hides

them from an eye aloft. At length the eagle pauses, excitedly. Some defect

in the shading has betrayed the quarry. Some imperfect feather has crept in

unaware. Some careless touch of a brush not dipped in heather. Nature

condones no mistakes, not even her own.

And we shoot the artist. It

is barbarous. Had there been as many silly people, long ago, to kill out

nature's agents, the red grouse, as we delight to have it, would never have

been evolved. Yet we strive to bring about a condition of things in which it

will be no longer needful to have russet hues for hiding. Nor will all the

wit of man stay them from fading, or put them back where they were. As a

painter without his brush, the moor will show its helplessness in the

absence of living agents. From its own palette the heather will not lay on a

single hue. Reversion will set in, and charm will go. The true enemy is not

the eagle. But it is not all tinting. Something else is in the conception of

a bird.

The falcon seeks game mainly

on the wing. She loves the stern chase, the lofty air perch, the swift and

fatal stoop. There is reason in shooting the falcon. How mean and

unsportsmanlike the reason will appear. She exacts her toll from the moor.

Of a covey of grouse, she will have one. Which one?

Some say the weakling; that

which lags, because it may not keep pace with the others and falls an easy

prey. A plea has been urged for her on this very account. For are not these

weaklings most likely to contract infection-if not already victims of

incipient disease-and spread havoc among the rest? It is good that the

devastating career should be stopped. And is not she the physician of

nature?

I am less disposed to make

use of this than once I was; partly because I see something better that may

be said. It is based on imperfect observation, and still more faulty

appreciation of larger issues. Pity if it were true, seeing that it would

involve more loss than gain. There are birds-I know a few-possessed of the

passion of flight, - that strain on the wing for the very joy of putting

forth their energies. There are birds of prey which rejoice more in the

pursuit than the capture. All have a liking for the chase. The rarer like it

well. The rarest of all is the peregrine. Its sporting qualities are matter

of history and tradition. It is too late to blacken its character.

That she - for the female is

the falcon - will strike unworthy fugitives, with none other in sight, is

true enough. But he, who has seen her turn contemptuously away without

taking the trouble to kill, will not suppose that she prides herself in the

deed. In a covey, with the strong birds straining before, to say that she

will stay her career at the laggard is altogether to mistake her mood. The

one fitter than the rest is the falcon's aim. If this be crime then she is

guilty, but we respect her the more. She is a noble criminal. On the whole,

I do not think that the falcon deems grouse worthy quarry, or is seen at her

best on the moor. There are arenas of greater stress, birds of nimbler

flight.

Grouse rise heavily before

the sportsman-so heavily as to suggest a startled effort to escape that way

when no other seemed open. It may well be so. Flight itself may have come

into being, as a refuge from ground enemies not to be distanced, or

outwitted, on the level. Wild creatures would not take to the wing without

stimulus ; nor apart from some such use would flight, once attained, have

been preserved. Those who could rise above reach, and get along a little way

with a flapping motion, would have the best chance of surviving.

When the bird first sprung

from the reptile, the air was empty of danger. A lumbering flight was good

enough, and would probably have been the highest stage reached. A further

stimulus was needed. That came in the form of winged enemies; pursuers in

the same element, and of their own kindred. From such are the perfection,

and all the marvellous mechanism of flight. To distance the pursuer, a bird

had to put on all its speed. It could put on no more than it had received.

But some were quicker than the rest. The slow perished by slow-winged hawks.

The quicker survived, to raise quicker broods. And, so the limits of speed

were increased. That there might be no relaxing of the strain, no

resting-place in the course of evolution, on the track of the swifter was

the swift-winged falcon.

Where speed failed, wiles to

elude were tried, which test the stroke of the hawk. The pursuer became

still more wonderful than the pursued, inasmuch as it had to outfly and

outmanoeuvre. Flight was moulded, its forward impulse lent, its every subtle

bend and graceful curve acquired in this school. If we have thought

otherwise, it will be well to unlearn the rustic creed.

What tests the hawk tests

also the skill of the marksman. But for such discipline, sport were wholly

wanting in zest, nor would it have known the supreme test of a flying shot,

or how to meet a tricky flight. Only ignorance can excuse the gracelessness

with which this debt is repaid. Such is so much of the story of life in the

open as is influenced by these two forms.

If we assume a sculptor, they

are the chisel; a painter, they are the brush. They did everything except

create. The falcon gave the flight feathers, lengthened and pointed the

wing. The eagle touched the plumage with moorland hues, whose charm was the

greater because of the exquisite sympathy. The reaction is marked; the eye

of the eagle became keener. Even the byplay is of infinite interest. The

protective shades of grouse give the nose of the pointer; less cunningly

hidden, and a coarser sense were enough. An interesting three are grouse,

sportsman, and dog. The hawk established their delicate relations.

Time was when people minded

these things. If they did not think of them quite in this way, the result

was the same. They let Nature alone, as old enough to manage her own

affairs. The love of mammon and all unrighteousness was not yet awake. With

the instinct of fair play, which is the vital spark of sport, they gave each

a chance. Their little differences they let the wildlings settle among

themselves, and found it greatly to the health, and altogether to the joy of

the moor. More clearly does this come out now that there is little health

and less joy. It gave the detachment from butchery needful to make it a

recreation for gentlemen.

Old servants stayed with

their olden masters, and it was found to be good for both. The lesson

applies to the moor. That the old servants there may be turned off without

loss is not the case. Looseness will slip in, and want of sympathy; with

attendant risk and ultimate decay. The loss may well be by littles, but so

was the gain. The present generation of sportsmen may not see the undoing,

neither did they see the doing. In their last season grouse will be shaded,

as they were on the first.

Nature never alters her ways,

either in the giving or the taking. She is wondrous kind even to the renters

of moors; she shows so little at a time.

Nor will new servants fill

the place of the old, in the open any more than they do in the house. The

eye of the gamekeeper is nothing to the eye of the hawk. The two do not mean

the same thing. The one has a narrow, the other a far outlook. One works for

his employer, the other in the interests of the moor. The one is there to

keep the birds wild, the other to make them tame.

And tame they will become; by

degrees, perhaps, but steadily. Half the wildness of wild creatures is a

continuous fear and watchfulness; half the tameness is to have no enemies.

Disturb the balance of nature, and you have no nature in either scale. The

falcon which strikes the fittest, points on to a fitter still-an ideal

beyond. In her absence is reversion to the reality behind, barely covered

out of sight. Kill her and with the same bullet you kill the grouse as you

know it, and arrest sport.

Straining after the leader of

the covey she appeals to chivalry and every sportsmanlike instinct. Between

the shooter of large bags on easy terms and the peregrine, the bird has the

truer spark. She loves sport for its own sake, and seeks to win in a fair

heat. The bird, which by reason of speed or resource escapes, she probably

respects, and will measure herself against some other day. Her appetites are

secondary; her sporting instincts dominate. She prefers the sauce of chase,

and the more piquant the better. She will leave a languid capture in midmeal

at the challenge of some nobler quarry.

From Sutherlandshire, the

report, 15th January 1898, was that golden eagles abounded over the county,

being preserved by the Duke. Falcons were to be met with. No word of

protection. No change has come about since. Eagles are increasing, not

falcons ; and that where the proprietor is humane and the policy liberal. So

it is all over Scotland, protection of the golden eagle, except where the

illiberal or inhumane kill both. Always the falcon that is left to her fate.

One is sometimes tempted to wish that it were the other way.

In all but size, the falcon

is the nobler. She is neither so loose nor so lumbering, nor so gross of

appetite, nor so indifferent, where and how she finds her prey. In the

golden eagle appetite is first, the sporting instinct is absent. Within

limits he may have his preferences. Mountain hares are more easily seen than

sitting, and more readily caught than flying game. Should there be a dying

lamb, or the carcass of a sheep about, even the mountain hare is safe for

the day; he will gorge himself. No love of chase for its own sake, nor sense

of fair play, nor trace of chivalry, is there. For the rest he is sullen,

cruel, and treacherous.

The falcon has the better

part, utterly without grossness of habit or any meanness of spirit. Proud is

she, almost to haughtiness. A wonderful picture of wild life is that where

she lands on the ledges of rock over her captive. Impatience is in the act

of twisting the neck and tossing the head away. The talons relax, the keen

eyes flash as a swifter wing comes in sight. And with her sterner qualities,

she is gentle and tractable, so that she will sit on a lady's wrist.

Chivalry in feathers appeals

to knightly men; this sporting bird that would rather a long chase than an

easy capture, rather a swift wing than a fat meal, appeals to all true

sportsmen. For the rest - whose spirit is different - possibly she despises

them as she does the mean among birds, and when she receives the bullet

casts an undaunted look down on the shooter.

With her clean habits and

disdainful mood, she does not readily succumb to the vulgarity of a trap, or

the cunning of a bait. She will starve before she will stoop. She may be

shot, but she will not be tempted. Therefore the frequent reports from the

remoter districts, 'Peregrine common, though destroyed when seen.' Like

enough is she to hold her own and return, if not the same, then another

peregrine, till men's eyes are opened to the colour of their actions. The

falcon for a looking-glass may help them to see their likeness.

Only fixed at the nesting

time, even then she chooses a lodgement for her brood, wild, often

inaccessible, a fit background for her and their picturesque personality. No

more exhilarating sight is there than the young falcons in their nest on the

giddy ledge, looking boldly out on the dwarfed glen or silent surf.

Fearless, they will strike at the man swung over from above, on a rope.

Only the other day some of

the more offensive of the tourist cult, after tormenting some ravens, found

a cleft or goat track by which they could approach an aerie. In vain the old

birds sought to divert or daunt them. The falcon shot, the less bold tiercel

withdrew. These out of the way they reached the nest, and threw the young

into their game sack. It is not pleasant to think such things are done, that

such gunners should be allowed to kill nobler creatures than themselves. It

has an ugly resemblance to other kinds of shooting, and should teach to shun

the very appearance of being one in such a fellowship.

On putting aside the gun, one

may lay the flattering unction to his soul that, after all, no great harm

has been done; not in such a short life as ours, no very apparent harm. A

dying sportsman should seek a cleaner record than that. He should be able to

say—I have meant no harm, I have done no unfair deed, taken no mean

advantage, spoiled no other creature’s play. Were I to live it over again, I

see nothing I should care to alter.

|