|

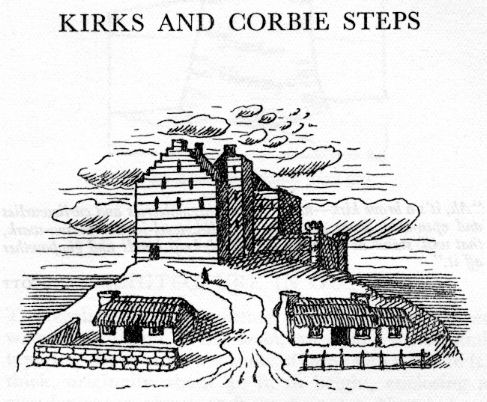

"Ah, it’s a brave kirk—nane

o'yere whigmaleeries and curliewurlies and open-steek hems about it—a’

solid, weel-jointed mason-wark, that will stand as lang as the warld, keep

hands and gunpowther aff it."

Scott

ARCHITECTURE IN OUTLINE

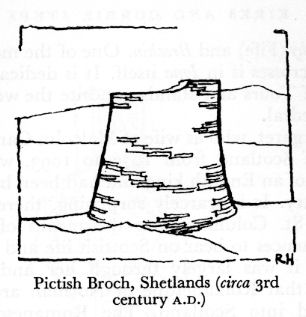

THE

earliest type of building you are likely to

meet with in Scotland is the broch, an open, round and tapering

tower superbly built of stone slab walls 16 ft. thick, originally about 40

ft. in height, enclosing a circular space about 40 ft. in diameter. No

windows pierce the walls, only a small door, while within the walls are

built galleries, cells and stairs, and a hearth and a well occupied the

centre space. Many brochs exist in the north and west of Scotland, dating

mostly from the first to the fifth centuries A.D., and they were used

either as a defence against sea-raiders or as the castles of a conquering

aristocracy. They are stark and solemn and have no parallel outside

Scotland.

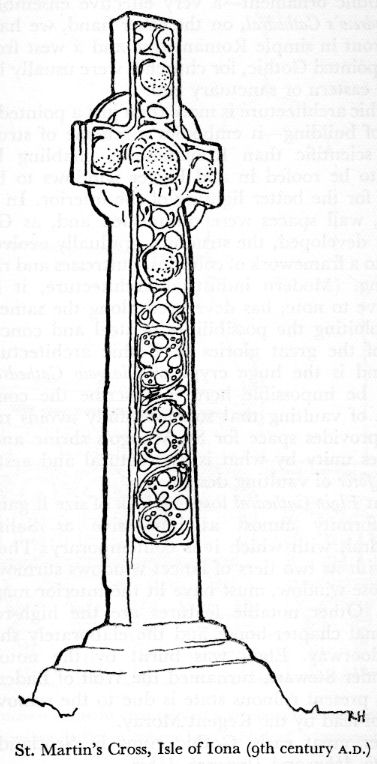

The arrival of Columba at

lona from Ireland in the sixth century and his missionary successes among

the Picts on the Scottish mainland were the means of establishing cultural

relations between Ireland and Scotland. The architectural consequences

were, briefly, the hermit’s cell (to be seen at Inchcolm), the carved

Celtic cross, the square-ended plan for churches and the tall round refuge

towers to be seen at Abernethy

(Fife) and Brechin. One of the most

perfect of Celtic crosses is in lona itself. It is dedicated to St.

Martin of Tours and stands opposite the west door of the Cathedral.

St. Margaret, who as wife of Malcolm

Canmore was Queen of Scotland from

1070 to 1093, was granddaughter of an

English king and had been brought up in Hungary. It is scarcely

surprising, therefore, that she, like St. Columba, was the means of

bringing fresh influences to bear on Scottish life and architecture, and

it was largely through her and her son, David I, that Romanesque or Norman

architecture penetrated into Scotland. The Romanesque characteristics are

the round arch, generally massive proportions, flat wooden ceilings and

long narrow churches. The large Scottish churches of this time rank among

the great ones of Europe. Kirkwall Cathedral, begun in 1137,

is a noble building originally planned

in the orthodox Norman manner with a central tower, transepts with eastern

chapels, nave of seven bays, choir of three and a single eastern apse. The

interior is very high for its width. Dunfermline Abbey church nave

was the work of David I and is reminiscent of Kirkwall. (Note especially

the two spirally fluted and two incised columns at the east end.) The west

façade of Jedburgh Abbey is another important and striking example

of Norman work.

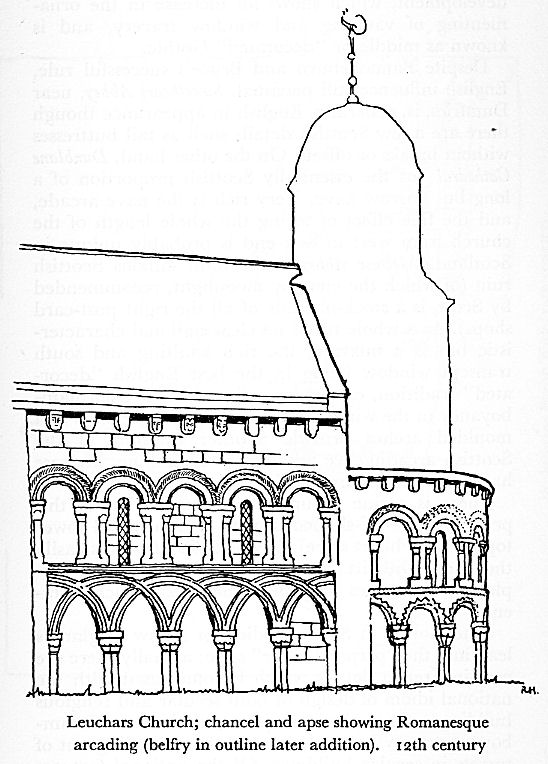

Several small Norman churches show

the influence of the square-ended Celtic plan—St. Oran’s at lona,

Stobo and Aberdour are all churches of this type that finds

no similar expression outside Scotland. The more usual Norman plan, with

an apse, can, of course, be seen at Dalmeny Church (which is

superb) or at Leuchars.

Scots were (and are) very fond of

sticking to certain features of building design long after they had been

dropped elsewhere, and the round arch is an example of this eclectic

conservatism; at the Nunnery chapel, lona

(1203), we find a round-arched arcade

accompanied by Gothic ornament—a very effective ensemble. At St. Andrew’s

Cathedral, on the other hand, we have an east front in simple Romanesque

and a west front in early pointed Gothic, for churches were usually begun

at the eastern or sanctuary end.

Gothic architecture is more than

just a pointed-arch style of building—it embodies a scheme of structure

more scientific than Romanesque, enabling larger areas to be roofed in and

bigger windows to be inserted for the better lighting of the interior. In

other words, wall spaces were diminished and, as Gothic design developed,

the structure gradually evolved itself into a framework of columns,

buttresses and ribbed vaulting. (Modern industrial architecture, it is

instructive to note, has developed along the same lines by exploiting the

possibilities of steel and concrete.) One of the great glories of Gothic

architecture in Scotland is the huge crypt of Glasgow Cathedral. It

would be impossible here to describe the complex system of vaulting that

so successfully avoids monotony, provides space for St. Mungo’s shrine and

yet achieves unity by what is a structural and aesthetic tour deforce

of vaulting design.

What Elgin Cathedral loses by

lack of size it gains by a uniformity almost as impressive as Salisbury

Cathedral, with which it is contemporary. The east end, with its two tiers

of lancet windows surmounted by a rose window, must have lit the interior

magnificently. Other notable features are the high-roofed octagonal

chapter-house and the elaborately shafted west doorway. Elgin was burnt by

the notorious Alexander Stewart, surnamed the Wolf of Badenoch, but its

present ruinous state is due to the removal of the roof-lead by the Regent

Moray.

Other great early Gothic ruins in

Scotland are Arbroath Abbey and Dryburgh Abbey.

From the simplicity of early Gothic

with its lancet

windows ("Early English") we proceed

to the next development, which shows an increase in the ornamenting of

vaulting and window tracery, and is known as middle or "decorated" Gothic.

Despite Bannockburn and Bruce’s

successful rule, English influence still persisted. Sweetheart Abbey,

near Dumfries, is, generally, English in appearance though there are a

few Scottish details such as tall buttresses without breaks or offsets. On

the other hand, Dunblane Cathedral has the essentially Scottish

proportion of a long but narrow nave. Very rich is the nave arcade, and

the fine effect of seeing the whole length of the church from west to east

end is probably unique in Scotland. Melrose Abbey is the most

famous Scottish ruin (of which the view by moonlight, recommended by

Scott, is a stock-in-trade of all the right post-card shops). As a whole

it has no clear national characteristic but is a mixture, the rich

vaulting and south transept window being in the best English "decorated"

tradition, except for a flavour of French flamboyancy in the windows,

while the shafted pillars and moulded arches provide another example of

the Scottish arcading we admired at Dunblane. Melrose has the usual

Cistercian plan.

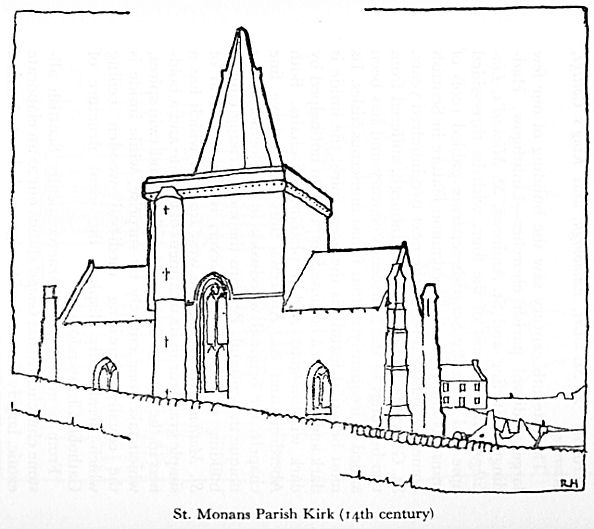

There is a fine group of parish

churches of this period in Fife (T-shaped in plan with a broad tower

topped by a blunt spire), of which St. Monans is easily the finest,

with its "decorated" window tracery displaying sometimes English,

sometimes French influence.

Late Gothic in Scotland did not

follow England’s lead into the "perpendicular" style; actually there are

certain French details which become fused with the national idiom of

design of both secular and religious buildings—the revival of apses and

the use of flamboyant tracery in windows, and the corbelling out of

turrets in secular buildings. Of the national features which developed

about now are the naïve curvilinear tracery, the stone slabbed roofing (to

be seen at Seton and Corstorphine), the elaborate

"Sacramental Houses" for the Elements, such as we see at Kintore

and Crichton churches, and lastly, the well-known open spires or

"crowns" at St. Giles, Edinburgh, and

King’s College, Aberdeen.

The fifteenth century saw the

building of our few large medieval parish churches—Linlithgow, Haddington,

Stirling and St. Andrews. St. Michael’s, Linlithgow, is the finest

of the four, with its three-sided apse and typically Scottish separate

gabled roofs of transepts and a porch—a common feature in Scottish

domestic architecture for the next two hundred years. St. Giles, the High

Kirk of Edinburgh, suffered from two burnings in the fourteenth century

and has been added to frequently so that it has numerous aisles. Its most

beautiful feature is the open spire: the inside is dark and conveys a

confused impression not helped by dark window-glass and a plethora of

chairs. Both Aberdeen and St. Andrews universities have fine chapels, the

original woodwork in the former being unique in Scotland. Perhaps the most

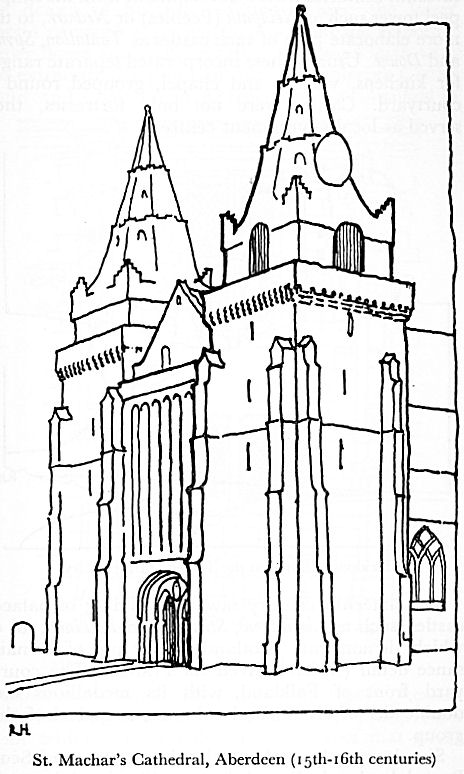

striking church building of this time, however, is the cathedral of St.

Machar, Aberdeen, the west front of which has a simple grandeur in its

treatment of granite and a boldness in the general design of windows and

twin spires, which takes one entirely by surprise, while inside is the

equally surprising medieval wooden ceiling which heraldically displays the

ideal structure of Catholic Christendom.

From a number of characteristically

Scottish all-stone churches, Roslin Chapel stands out as an

elaborate exotic, largely the work of foreigners. It has to be seen to be

believed.

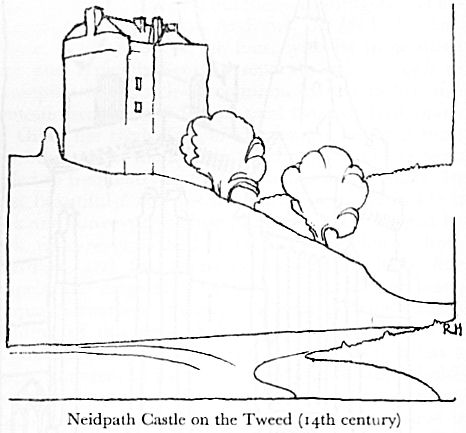

The earliest medieval secular

buildings are thirteenth-century stone keeps (Dunstafnage or

Inverlochy), usually built with stone surrounds on promontories

overlooking river or loch, During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries

we see development from the simple peel tower such as Neidpath

(Peebles) or Newark, to the more elaborate plan of such castles as

Tantallon, Spynie and Doune. Usually these incorporated

separate ranges for kitchens, visitors and chapel, grouped round a

courtyard. Castles were not only fortresses, they served as local

government centres.

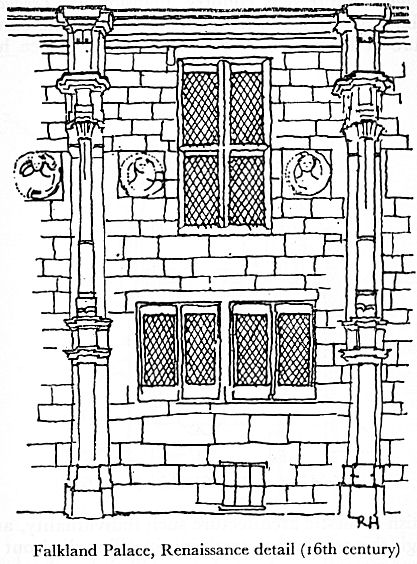

The sixteenth century saw the

building of palace-castles, such as Linlithgow, Stirling and

Falkland, all of which demonstrate Scotland’s early use of Renaissance

detail (which arrived via France). The courtyard front of Falkland,

with its medallions and double tier of ornamental columns, is typical of

this group.

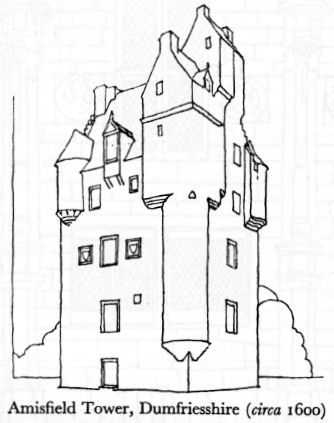

Simultaneously we have the

development of Scots Baronial, wherein French features like the

elaborately corbelled turret were welded with naïve ingenuity into the

design of Scottish fortified houses, the lower storeys of which were left

plain so that the elaborate upper floors and roof structure blossomed

forth with the extraordinary profusion that characterises Castles

Fraser and Craigievar in Aberdeenshire or Amisfield in

Dumfriesshire. Allied with this evident vigour of essentially

functional [Functional: a style of building wherein convenience and the

claims of structure dominate design, taking little heed of external

symmetry.] design was a sure sense of proportion—for seldom, if ever, do

we find a roof that seems "wrong" in shape.

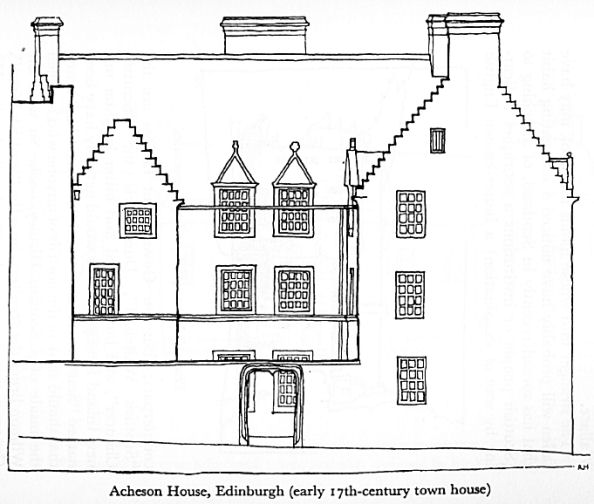

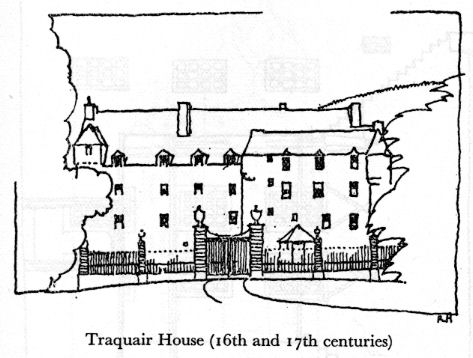

Meanwhile the ordinary house took

form and a few remaining examples reveal its naive and varied charm.

Perhaps the most interesting town houses are Provand’s Lordship,

Glasgow, The Palace, Culross, Acheson House, Edinburgh and

Argyll’s Lodging, Stirling, while by far the most impressive

country mansion is Traquair, rambling yet shapely, its lines

softened by the casual texture of harling. At no time before or since had

Scottish domestic architecture such individuality, and though this

wholesome tradition in effect died out in the seventeenth century, being

killed by the later Renaissance, it persisted much longer in cottage and

farm buildings: it was the native idiom.

Two buildings occur about this time

which will strike the reader as out of the normal course. Heriot’s

Hospital and Wintoun House have generally a flavour foreign to

the strongly national tendencies of contemporary architecture. Their

details, notably the chimneys at Wintoun, are markedly English, and they

were built, it transpires, by the same master of works, Wallace.

The stranger into whose hands this

book may have fallen will probably have noticed a nauseating habit that

has spread recently in Scotland, of attaching to (Scottish people or

institutions a sobriquet indicating by way of exaplanation) a better-known

English counterpart; thus our Government Offices are the "Scottish

Whitehall", Dunbar is the "Scottish Chaucer", and but for loud and bitter

laughter our new Inland Revenue offices would actually have been named

"Somerset House"—and "Somerset" is a name that should stink in the

nostrils of anyone who has seen the inside of a Scottish History book. So

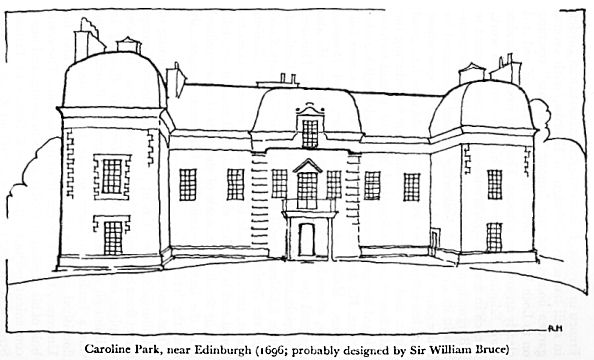

with Sir William Bruce the architect, he is the "Scottish Wren".

Contemporary he certainly was, but little else. His most complete work is

Kinross House and garden, his most famous the main court of

Holyroodhouse. Both are refined and neither is the least English, but

rather

French in flavour. It is rare to

find a house and garden in such harmony of design as Kinross, with several

garden houses and the famous "Fish-gate" opening on to Loch Leven. Bruce

built it for himself and it is clearly an architect’s house. The 1691

front of Caroline Park, Edinburgh, is probably his most original work.

French in general appearance—it has been likened to a Burgundian

manor-house—but unmistakeably Scottish in its sly detail. Following on and

influenced by Bruce came William Adam, the father of sons whose fame has

eclipsed his own. But the old man had great talent, and as he was

responsible for introducing the Palladian style into Scotland, he may be

said to have bridged the gulf between Scottish and English architecture.

He designed Yester House, The Drum near Gilmerton, Mellerstain near the

Border, and Hopetoun House, where he incorporated work by Bruce. He also

designed the now demolished Town House at Dundee. His celebrated sons did

most of their work in England, but in Edinburgh will be found their

University Buildings, the Register House and the magnificent Charlotte

Square, the north side of which has recently been restored and is worth a

visit; it is well massed yet delicate in detail. The work of the sons is

more refined than the father’s—sometimes it comes dangerously near the "refaned".

The best monument of this age is the planning of

Edinburgh’s New Town; the view down George Street from St. Andrew Square

gives perhaps the most complete impression. Adam’s University Building in

Edinburgh was finished and altered by Playfair, who was a leading

architect of the Greek revival that flourished in the early nineteenth

century, and his University dome is of excellent proportions. The

vestibule of his Academy at Dollar is worth seeing, and more convenient

perhaps, the National Gallery in Princes Street and the fine façade of

Royal and Regent Terraces in Edinburgh. Hamilton was another important

architect of the time, and his Royal High School is a bold Athenian

group of buildings of grace and dignity on the rocky slopes of the Calton

Hill, Edinburgh. The Greek revival was strongly expressed by "Greek"

Thomson in the west of Scotland, and his St. Vincent Street Church,

Glasgow, is easily the most striking example of this movement. Note how

splendidly the advantage of the sloping site has been used.

And now we come to what is the very depth of Scotland’s

architectural winter, for the neo-classicism of the Adams and the Greek

revival almost knocked the life out of native architecture, which retired

to obscure farm buildings and cottages.

Thirst for the romantic impelled our fathers and

grandfathers to revive Scots Baronial as a style. Probably their most

thorough revivalist debauch is epitomised in Balmoral, but the

habit spread throughout the kingdom, ranging in expression from the

mansions of county families to the turreted villas of Edinburgh’s suburbs.

And of course there was Abbotsford. Of these all that can be said

is "Non ragioniam di lor, ma guarda e passa".

As imitations of the real thing they are all depressingly amateurish,

they abound in restless lines and hard textures, and their interiors are

veritable forests of varnished pitch-pine.

Gothic was, of course, deemed the essential of a good

church, but few churches were in scholarly Gothic. The general tendency

was towards an attenuated style of little vitality. The development of an

architectural idiom suited to Presbyterian worship unfortunately made no

headway, for a Scottish church was after all a place for the preaching of

the Word, not a shrine for sacraments and contemplation, as most original

Gothic buildings had been.

Largely owing to the zeal of Sir Rowand Anderson,

revivalism was directed to real research into Scottish tradition, as his

excellent restoration of Dunblane Cathedral testifies, and his work

was developed by

Sir Robert Lorimer, the architect of the Scottish

National War Memorial. The Scottish tradition, not fully understood,

it is true, became popular and Lorimer throve as a fashionable architect,

the "Lutyens" —let us too commit the nauseating sin—of Scotland. And

truly, few buildings can have caught the public imagination as fully as

Lorimer’s war memorial, whatever we may think of it architecturally.

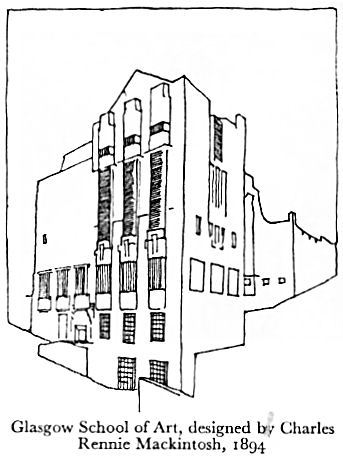

But the real hope of Scottish architecture does not lie

with Lorimer or his followers. In 1894 a young architect, C. R.

Mackintosh, suddenly produced his design for the Glasgow School of Art,

a piece of pioneer modernism which has had more influence on modern

European architecture than any other building of its time. Here are the

seeds of modern "functional" architecture, and, if we have eyes to see, we

shall realise how much Mackintosh owed to the sturdy functional tradition

of sixteenth and seventeenth-century Scottish architecture. His houses at

Helensburgh and Kilmacolm tell the same tale. But Mackintosh was a prophet

in his own country and it is only now he is dead that we begin to give

true recognition to his genius. |