As Henry had predicted, during the autumn the whole

family were fully employed. The stock had increased very much; they had

a large number of young calves and heifers, and the sheep had lambed

down very favourably. Many of the stock were now turned into the bush,

to save the feed on the prairie. The sheep with their lambs, the cows

which were in milk, and the young calves only were retained. This gave

them more leisure to attend to the corn harvest, which was now ready,

and it required all their united exertions from daylight to sunset to

get it in, for they had a very large quantity of ground to clear. It

was, however, got in very successfully, and all stacked in good order.

Then came the thrashing of the wheat, which gave them ample employment;

and as soon as it could be thrashed out, it was taken to the mill in the

waggon, and ground down, for Mr Campbell had engaged to supply a certain

quantity of flour to the fort before the winter set in. They

occasionally received a visit from Captain Sinclair and the Colonel, and

some other officers, for now they had gradually become intimate with

many of them. Captain Sinclair had confided to the Colonel his

engagement to Mary Percival, and in consequence the Colonel allowed him

to visit at the farm as often as he could, consistently with his duty.

The other officers who came to see them, perceiving how much Captain

Sinclair engrossed the company of Mary Percival, were very assiduous in

their attentions to Emma, who laughed with and at them, and generally

contrived to give them something to do for her during their visit, as

well as to render their attentions serviceable to the household. On

condition that Emma accompanied them, they were content to go into the

punt and fish for hours; and, indeed, all the lake-fish which were

caught this year were taken by the officers. There were several very

pleasant young men among them, and they were always well received, as

they added very much to the society at the farm. Before the winter set

in the flour was all ready, and sent to the fort, as were the cattle

which the Colonel requested, and it was very evident that the Colonel

was right when he said that the arrangement would be advantageous to

both parties. Mr Campbell, instead of drawing money to pay, this year,

for the first time, received a bill on the Government to a considerable

amount for the flour and cattle furnished to the troops; and Mrs

Campbell’s account for fowls, pork, etcetera, furnished to the garrison,

was by no means to be despised.

Thus, by the kindness of others, his own exertions, and a judicious

employment of his small capital, Mr Campbell promised to be in a few

years a wealthy and independent man.

As

soon as the harvest set in, Malachi and John, who were of no use in

thrashing out the corn, renewed their hunting expeditions, and seldom

returned without venison. The Indians had not been seen by Malachi

during his excursions, nor any trace of their having been in the

neighbourhood.

All alarm, therefore, on that account was now over, and the family

prepared to meet the coming winter with all the additional precautions

which the foregoing had advised them of. But during the Indian summer

they received letters from England, detailing, as usual, the news

relative to friends with whom they had been intimate; also one from

Quebec, informing Mr Campbell that his application for the extra grant

of land was consented to; and another from Montreal, from Mr Emmerson,

stating that he had offered terms to two families of settlers who bore

very good characters, and if they were accepted by Mr Campbell, the

parties would join them at the commencement of the ensuing spring.

This was highly gratifying to Mr Campbell, and as the terms were, with a

slight variation, such as he had proposed, he immediately wrote to Mr

Emmerson, agreeing to the terms, and requesting that the bargain might

be concluded. At the same time that the Colonel forwarded the above

letters, he wrote to Mr Campbell to say that the interior of the fort

required a large quantity of plank for repairs, that he was authorised

to take them from Mr Campbell, at a certain price, if he could afford to

supply them on those terms, and have them ready by the following spring.

This was another act of kindness on the part of the Colonel, as it would

now give employment to the saw-mill for the winter, and it was during

the winter, and at the time that the snow was on the ground, that they

could easily drag the timber after it was felled to the saw-mill. Mr

Campbell wrote an answer, thanking the Colonel for his offer, which he

accepted, and promised to have the planks ready by the time the lake was

again open.

At

last the winter set in, with its usual fall of snow. Captain Sinclair

took his leave for a long time, much to the sorrow of all the family,

who were warmly attached to him. It was now arranged that the only

parties who were to go on the hunting excursions should be Malachi and

John, as Henry had ample employment in the barns; and Martin and Alfred,

in felling timber and dragging up the stems to the saw-mill, would, with

attending to the mill as well, have their whole time taken up. Such were

the arrangements out of doors, and now that they had lost the services

of poor Percival, and the duties to attend to indoors were so much

increased, Mrs Campbell and the girls were obliged to call in the

assistance of Mr Campbell whenever he could be spared from the garden,

which was his usual occupation. Thus glided on the third winter in quiet

and security; but in full employment, and with so much to do and to

attend to, that it passed very rapidly.

It

was in the month of February, when the snow was very heavy on the

ground, that one day Malachi went up to the mill to Alfred, whom he

found alone attending the saws, which were in full activity; for Martin

was squaring out the timber ready to be sawed at about one hundred

yards’ distance.

“I

am glad to find you alone, sir,” said Malachi, “for I have something of

importance to tell you of, and I don’t like at present that anybody else

should know anything about it.”

“What is it, Malachi?” inquired Alfred.

“Why, sir, when I was out hunting yesterday I went round to a spot where

I had left a couple of deer-hides last week that I might bring them

home, and I found a letter stuck to them with a couple of thorns.”

“A

letter, Malachi!”

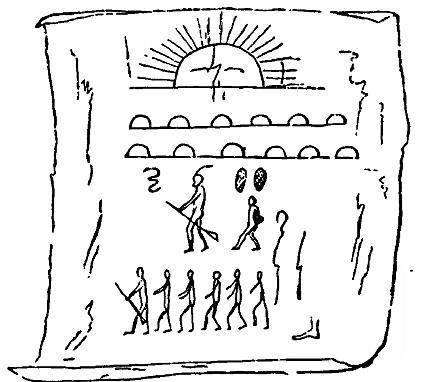

“Yes, sir, an Indian letter. Here it is.” Malachi then produced a piece

of birch-bark, of which the underneath drawing is a fac-simile.

“Well,” said Alfred, “it may be a letter, but I confess it is all Greek

to me. I certainly do not see why you wish to keep it a secret. Tell

me.”

“Well, sir, I could not read one of your letters half so well as I can

this; and it contains news of the greatest importance. It’s the Indian

way of writing, and I know also whom it comes from. A good action is

never lost, they say, and I am glad to find that there is some gratitude

in an Indian.”

“You make me very impatient, Malachi, to know what it means; tell me

from whom do you think the letter comes?”

“Why, sir, do you see this mark here?” said Malachi, pointing to the one

lowest down on the piece of bark.

“Yes; it is a foot, is it not?”

“Exactly, sir; now, do you know whom it comes from?”

“I

can’t say I do.”

“Do you remember two winters back our picking up the Indian woman, and

carrying her to the house, and your father curing her sprained ankle?”

“Certainly; is it from her?”

“Yes, sir; and you recollect she said that she belonged to the band

which followed the Angry Snake.”

“I

remember it very well; but now, Malachi, read me the letter at once, for

I am very impatient to know what she can have to say.”

“I

will, Mr Alfred; now, sir, there is the sun more than half up, which

with them points out it is the setting and not the rising sun; the

setting sun therefore means to the westward.”

“Very good, that is plain, I think.”

“There are twelve wigwams, that is, twelve days’ journey for a warrior,

which the Indians reckon at about fifteen miles a day. How much does

fifteen times twelve make, sir?”

“One hundred and eighty, Malachi.”

“Well, sir, then that is to say that it is one hundred and eighty miles

off, or thereabouts. Now, this first figure is a chief, for it has an

eagle’s feather on the head of it, and the snake before it is his totem,

‘the Angry Snake,’ and the other six are the number of the band; and you

observe, that the chief and the first figure of the six have a gun in

their hands, which is to inform us that they have only two rifles among

them.”

“Very true; but what is that little figure following the chief with his

arms behind him?”

“There is the whole mystery of the letter, sir, without which it were

worth nothing. You perceive that the little figure has a pair of

snow-shoes over it.”

“Yes, I do.”

“Well, that little figure is your brother Percival, whom we supposed to

be dead.”

“Merciful heavens! is it possible?” exclaimed Alfred; “then he is

alive!”

“There is no doubt of it, sir,” replied Malachi; “and now I will put the

whole letter together. Your brother Percival has been carried off by the

Angry Snake and his band, and has been taken to some place one hundred

and eighty miles to the westward, and this information comes from the

Indian woman who belongs to the band, and whose life was preserved by

your kindness. I don’t think, Mr Alfred, that any white person could

have written a letter more plain and more to the purpose.”

“I

agree with you, Malachi; but the news has so overpowered me, I am so

agitated with joy and anxiety of mind, that I hardly know what I say.

Percival alive! we’ll have him if we have to go one thousand miles and

beat two thousand Indians. Oh, how happy it will make my mother! But

what are we to do, Malachi? tell me, I beseech you.”

“We must do nothing, sir,” replied Malachi.

“Nothing, Malachi!” replied Alfred, with surprise.

“No, sir; nothing at present, at all events. We have the information

that the boy is alive, at least it is presumed so; but of course the

Indians do not know that we have received such information; if they did,

the woman would be killed immediately. Now, sir, the first question we

must ask ourselves is, why they have carried off the boy; for it would

be no use carrying off a little boy in that manner without some object.”

“It is the very question that I was going to put to you, Malachi.”

“Then, sir, I’ll answer it to the best of my knowledge and belief. It is

this: the Angry Snake came to the settlement, and saw our stores of

powder and shot, and everything else. He would have attacked us last

winter if he had found an opportunity and a chance of success. One of

his band was killed, which taught him that we were on the watch, and he

failed in that attempt; he managed, however, to pick up the boy when he

was lagging behind us, at the time that you were wounded by the painter,

and carried him off, and he intends to drive a bargain for his being

restored to us. That is my conviction.”

“I

have no doubt but that you are right, Malachi,” said Alfred, after a

pause. “Well, we must make a virtue of a necessity, and give him what he

asks.”

“Not so, sir; if we did, it would encourage him to steal again.”

“What must we do then?”

“Punish him, if we can; at all events, we must wait at present, and do

nothing. Depend upon it we shall have some communication made to us

through him that the boy is in their possession, and will be restored

upon certain conditions—probably this spring. It will then be time to

consider what is to be done.”

“I

believe you are right, Malachi.”

“I

hope to circumvent him yet, sir,” replied Malachi; “but we shall see.”

“Well; but Malachi, are we to let this be known to anybody, or keep it a

secret?”

“Well, sir, I’ve thought of that; we must only let Martin and the

Strawberry into the secret; and I would tell them, because they are

almost Indians, as it were; they may have someone coming to them, and

there’s no fear of their telling. Martin knows better, and as for the

Strawberry, she is as safe as if she didn’t know it.”

“I

believe you are right; and still what delight it would give my father

and mother!”

“Yes, sir, and all the family too, I have no doubt, for the first hour

or two after you have told them; but what pain it would give them for

months afterwards! ‘Hope deferred maketh the heart sick,’ as my father

used to read out of the Bible, and that’s the truth, sir. Only consider

how your father, and particularly your mother, would fret and pine

during the whole time, and what a state of anxiety they would be in!

they would not eat or sleep. No, no, sir, it would be a cruelty to tell

them, and it must not be. Nothing can be done till the spring at all

events, and we must wait till the messenger comes to us.”

“You are right, Malachi; then do as you say, make the communication to

Martin and his wife, and I will keep the secret as faithfully as they

will.”

“It’s a great point our knowing whereabouts the boy is,” observed

Malachi, “for if it is necessary to make a party to go for him, we know

what direction to go in. And it is also a great point to know the

strength of the enemy, as now we shall know what force we must take with

us in case it is necessary to recover the lad by force or stratagem. All

this we gained from the letter, and shall not learn from any messenger

sent to us by the Angry Snake, whose head I hope to bruise before I’ve

done with him.”

“If I meet him, one of us shall fall,” observed Alfred.

“No doubt, sir, no doubt,” replied Malachi; “but if we can retake the

boy by other means, so much the better. A man, bad or good, has but one

life, and God gave it to him. It is not for his fellow-creature to take

it away unless from necessity. I hope to have the boy without shedding

of blood.”

“I

am willing to have him back upon any terms, Malachi; and, as you say, if

we can do it without shedding of blood, all the better; but have him I

will, if I have to kill a hundred Indians.”

“That’s right, sir, that’s right, only let it be the last resort;

recollect that the Indian seeks the powder and ball, not the life of the

boy; and recollect that if we had not been so careless as to tempt him

with the sight of what he values so much, he would never have annoyed us

thus.”

“That is true; well then, Malachi, it shall be as you propose in

everything.”

The conversation was here finished; Alfred and all those who were

possessed of the secret never allowed the slightest hint to drop of

their knowledge. The winter passed away without interruption of any

kind. Before the snow had disappeared the seed was all prepared ready

for sowing; the planks had been sawed out, and all the wheat not

required for seed had been ground down and put into flower barrels,

ready for any further demand from the fort. And thus terminated the

third winter in Canada.